It was St. Joseph’s Night 2006, a group of volunteers set off from the New Orleans suburb of Arabi in search of Mardi Gras Indians. The neighborhood we were in was still without power, without mail service, largely without people. Almost no traffic lights worked between our camp and the parts of the city that had been spared the flood. Traveling into town at night was unsettlingly dark, flooded cars still jutted into the road.

Today kids doing the same thing would be documenting every second of their experience but I don’t think we even owned a camera among us. These days there are also websites telling you where to go but our strategy was to drive to Center City and just start asking around. The Mystery Gang piling out of a van asking which way the Indians went is a common enough occurrence in that neighborhood that we found what we were looking for almost immediately.

Most of my fellow volunteers had never heard of Mardi Gras Indians until I excitedly recruited them, and the van, for the experience. I only knew of them because that part of New Orleans street culture has become a point of pride in the city in the 40 years since Tootie Montana, and Bo Dollis and The Wild Magnolias, first appeared at Jazz Fest and opened some elements of the secret societies to public display.

The year before, while working in a French Quarter kitchen, I’d spent Mardi Gras morning listening to WWOZ broadcast the festivities of Indian Gangs as the gathered in Treme. Catching Indian practice at Vaughn’s became part of a pre-storm to-do list that never happened.

The first thing we saw that night was two gangs meet at an intersection outside of a corner store. The crowd was still small, each gang had four or so masked members and a handful of followers in street clothes. We watched as they played out their roles of Spy Boy, Wild Man, Flag Boy, and Big Cheif.

The first thing we saw that night was two gangs meet at an intersection outside of a corner store. The crowd was still small, each gang had four or so masked members and a handful of followers in street clothes. We watched as they played out their roles of Spy Boy, Wild Man, Flag Boy, and Big Cheif.

As they began to strut and chant and drum my first impression was of a rap battle. I was also reminded of Calypso recordings featuring insult exchanges I’d found on Smithsonian records.

It was a ritual meeting, the primary exercise of one of America’s most interesting and misunderstood folk cultures. And not at all what I had expected from “Iko Iko”, or the various fusions of New Orleans funk and Mardi Gras Indian standards that have found their way to a college radio audience.

We got caught up in the mix and had an unforgettable time as various streams of Black Indian gangs converged throughout the night eventually filling a major thoroughfare and being dispersed, amid some tension, by police.

Since then, when I’ve tried to explain what seeing an Indian event is like I’ve tried to turn to YouTube for help to no avail. The history is more easily available than it has ever been- there are excellent documentaries and mountains of video. Video of marching and parading and drumming. Video of amazing suits. Video of a dozen other people holding phones up.

But precious little video of the actual battles, and when you find them they don’t capture the feeling of being there in the heated shadow of the thing- when the battles seem to threaten the actual inter-neighborhood violence they serve to replace.

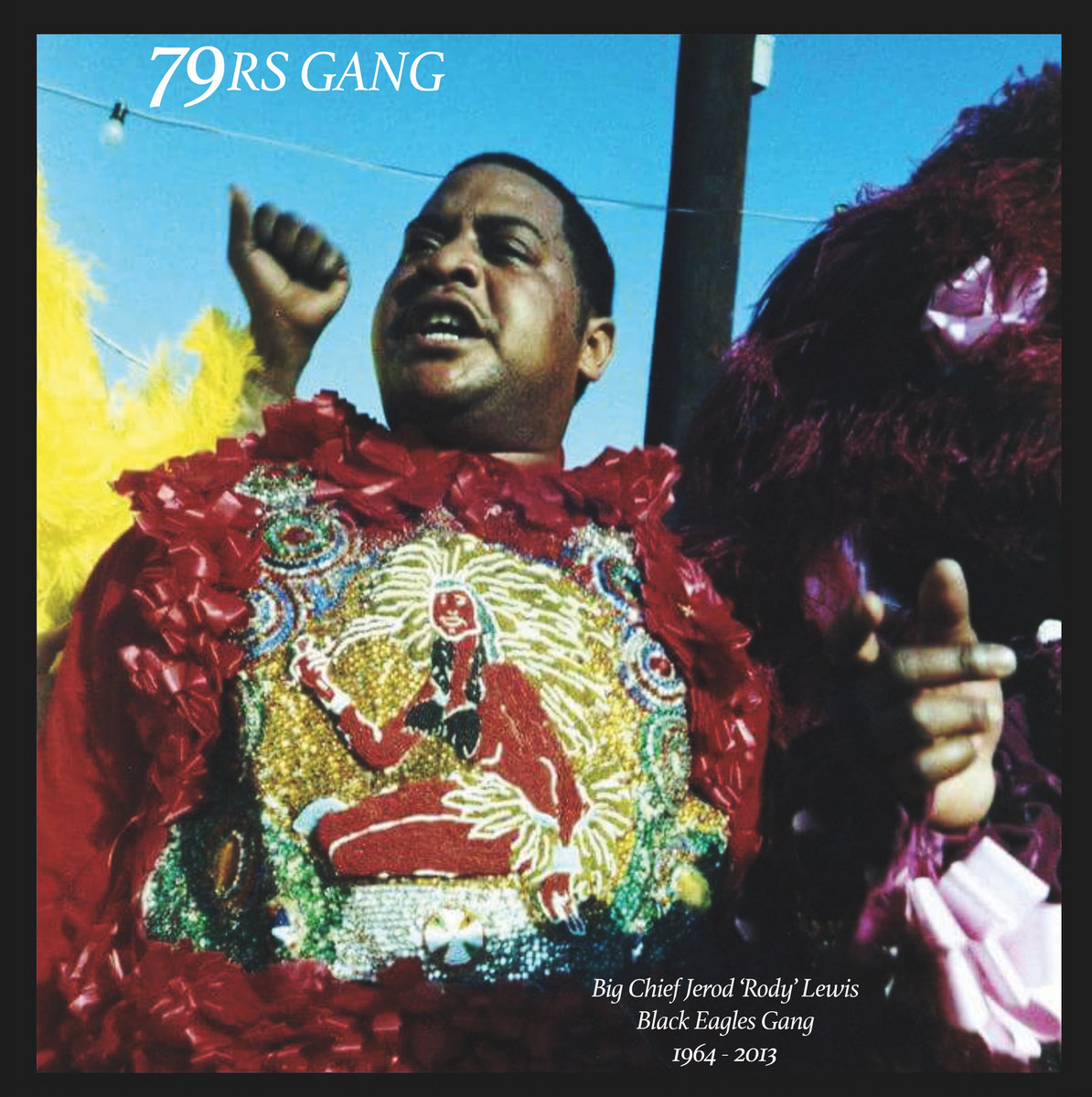

Which is why I was so excited to find this release from The 79ers Gang. It captures better than any studio release I’ve previously heard the actual feeling of being in the street. While they use the opportunity to record a smoother presentation then you’ll ever hear out on the battlefield they don’t add any of the extra frills other groups have relied on. Drum, hands, and voice is all you need. They also don’t sanitize the language or the beat to fit anyone’s sensibilities, it’s the raw thing.

The album is available as an LP which I purchased because the two-sided cover is so beautiful. They have since released a 7″ record of two more songs. Record purchases come with streaming and in this case, it feels worth it to have the physical thing.

The cannon of Indian standards is not large, some have written that it is as few as six basic chants, many of them shared with Second Line culture. I think there are quite a few more than that, but it explains why you’ll recognize at least a few of the titles on this album. “Indian Red”, “Shallow Water”, “Oh Na Nae”, and “Eh Paka Way” have all migrated into other styles of music.

There are two equally gratifying ways to enjoy this album. You can give it a deep ethnographical listen and add some aural experience to what you may have read or heard, or you can just let that drum beat hit you and groove. It will be hard not to do both. Aside from being the truest album of Mardi Gras Indian music I’ve come across it also has an absolutely contagious rhythm.