banjo; Earl McDonald – jug; Curtis Hayes, six-string banjo; Freddie Smith, plectrum banjo;

Clifford Hayes, violin.

Jeff Barnhart: This month we’re starting a two-part discussion about the music of the Dixieland Jug Blowers from the mid-1920s. I’ll freely admit I’ve only heard a scant handful of these tunes and, while I enjoyed them, didn’t pay close attention to them. So this month, I’ll join the likely majority of you, dear readers, to experience this little-known music for the first time! Our guide, as usual, is the redoubtable Hal Smith! Hal, this group sounds like nothing we’ve covered up to this point. Can you get us started by describing its origin, what makes it unique, and why it’s one of your favorite groups?

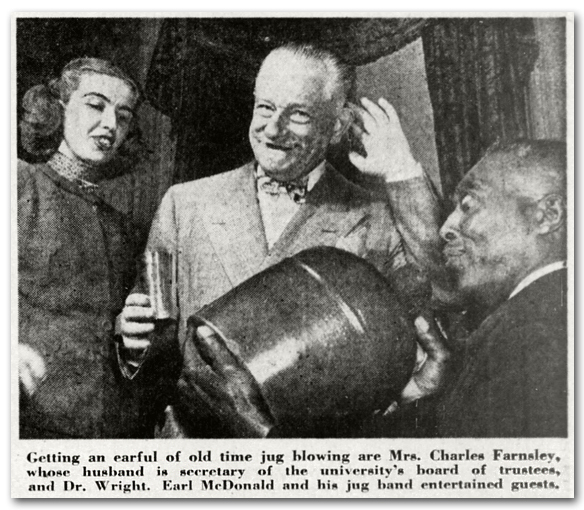

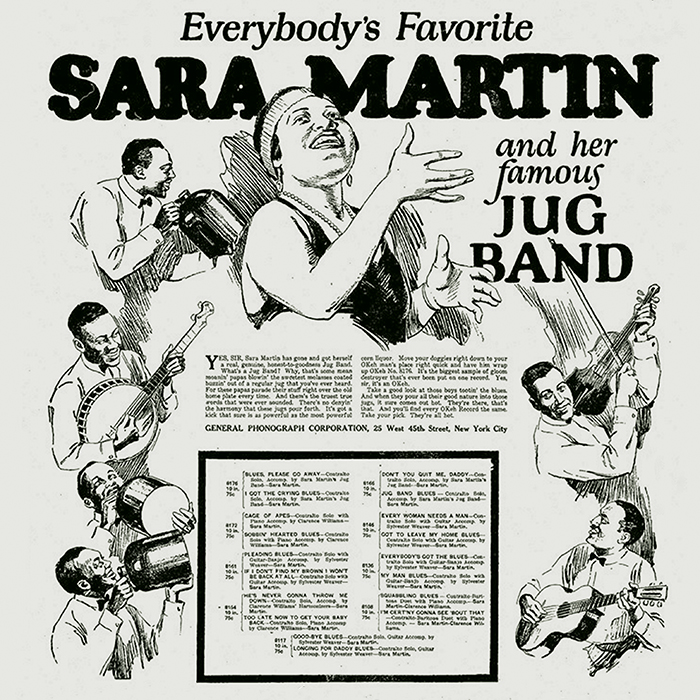

Hal Smith: Jeff, if I needed another reason to love the City of Louisville—besides composer/pianist Ben Harney, Evan Williams bourbon, and the L&N Railroad—it would be that jug band music originated there in the 19th Century! According to Ron Geesin, in his liner notes to Louisville Stomp (Frog CD DGF6), Earl McDonald was leading the Louisville Jug Band before WWI. The group performed at all kinds of functions, from private parties to the Kentucky Derby! They also played in New York and Chicago, where they played opposite the Original Dixieland Jass Band! Earl McDonald, violinist Clifford Hayes, and banjoist Cal Smith also made the first jug band recording in 1924—accompanying blues singer Sara Martin (an earlier recording, by “Fred Ozark’s Jug Blowers,” did not even include a jug player)!

Ron Geesin states that jug blower Henry Clifford convinced the Victor company to record a jug band in 1926. He lined up McDonald, Hayes and Smith for the recordings, which were released under the name “Dixieland Jug Blowers.” Others in the group included Lockwood Lewis, alto sax; Curtis Hayes, six-string banjo; Freddie Smith, plectrum banjo; and Clifford himself on jug. Victor recorded the band on two successive days: Dec. 10 and 11, 1926, at the Webster Hotel in Chicago. Incidentally, that’s the same location Jelly Roll Morton’s Red Hot Peppers recorded their classic sides earlier in the year!

The first song they recorded was “Boodle-Am-Shake.” We hear a hard-charging rhythm section made up of three banjos (tenor, plectrum, six-string), “tenor” and “bass” jugs and a front line with alto sax and violin (frequently doubling the lead). The combination of sophisticated banjo playing, the “country” sounds of the fiddle and jugs and the old-timey alto sax is unlike anything heard on records before or since! Jeff, what stands out for you on the first selection?

JB: This is a homespun, barnyard dance sound, with the exception of the alto sax. The sheet music for “Boodle-Am-Shake” reveals the composers to be Jack Palmer and Spencer Williams (who collaborated two years earlier on the much-better-known “Everybody Loves My Baby”) and the Dixieland Jug Blowers give it a raucous rendering! It keeps showing up in later years, most notably in a version by Jim Kweskin and also in 1964 by Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions, a band featuring Jerry Garcia and Bob Weir, soon-to-be cofounders of the Grateful Dead! I’d never heard the verse and the DJB are pretty cursory getting through it but the chorus has an infectious chord sequence and catchy melody.

It interests me that the duet vocal has virtually no harmony, rather like the relationship between the violin and alto sax you mentioned. I loved listening to the differences in the banjo and sax breaks of takes 1 and 2. I also noticed a marked difference in acoustics in that room at the Webster Hotel from the Red Hot Peppers dates. Was this aural dissimilarity brought about by a different engineer or perhaps the unique instrumentation? Finally, I was blown away by the resonance and clarity of that bass jug blown by Henry Clifford! No airy, “whoofy” sound here! In Geesin’s liner notes he mentions the long lineage and the competition in Louisville for bragging rights as the best blower. This is a great start Hal! What’s next?

HS: There are two takes of “Boodle-Am Shake” and the second version cleared up some of the missed breaks from take one. Following that, the DJB recorded a 1915 composition by William King Phillips entitled “Florida Blues.” It has a rag-a-jazz feel, typical of blues compositions from that era. After an ensemble chorus, Earl McDonald takes a very musical jug chorus. The three banjos add much to the ensemble sound on the choruses that follow (including a key change to Bb). McDonald returns to take a stoptime chorus, with Clifford Hayes accompanying him. Next, Hayes plays a doubletime feel over straight time before the banjos take up the doubletime rhythm and the full ensemble brings the performance to a close. I wonder if they all got a chuckle out of that coda by the two jugs!

The discography on the Frog CD notes that “Florida Blues” was a second take. The next song, “Don’t Give All The Lard Away,” was a third take. This song was composed by band members Henry Clifford and Lockwood Lewis and the chord structure on the chorus bears a strong resemblance to “Ballin’ The Jack.” There is a vocal verse and chorus by Lewis, with the band playing quietly in the background. A hot ensemble follows, with a jug break by McDonald and a pickup by Clifford that reminds me of Dick Lammi’s tuba playing with Lu Watters! Lewis sings another chorus, with some scatting, before the ensemble brings the performance to a rather abrupt ending.

What do you hear on these sides, Jeff?

JB: I still can’t get over the sonority of the bass jug, and YES, I immediately thought of Dick Lammi (as well as our dear departed friend Mike Walbridge) when I heard it. The sound from this band, with the rural violin and the three banjos (the tone and depth of Curtis Hayes’ six-string on these tracks is incredible) make me think hot southern days around the general store (or saloon) after a hard day in the fields on the farm. Hal, who was Victor records aiming for to buy these recordings? Also, where have we heard saxist Lockwood Lewis before in our articles?

HS: I’ll bet these recordings sold very well in Louisville! But remember that Victor recorded the Original Dixieland Jass Band way back in 1917. They knew what their customers wanted to hear. In fact, “Memphis Shake,” from the Dec. 11 session, was issued on the reverse of Jelly Roll Morton’s “Doctor Jazz!”

Lockwood Lewis, from Bowling Green, Kentucky, was a dance band musician, bandleader and vocalist. He played an old-fashioned, kind of flat-footed style similar to Junie Cobb on sax. By the way, there is a detailed description of how he came to be included in the DJB recordings, as well as the background on how the sessions were organized, in Storyville Magazine number 160 (Dec., 1994 – “The Jug Bands of Louisville,” Chapter 3, part 3). We mentioned Lockwood Lewis as a key band member of the Missourians in our discussion about the band.

JB: Thanks for reminding me; Lockwood Lewis is not an easy name to forget but I couldn’t remember where I’d seen it!! “Florida Blues” is filled with surprises. Highlights for me are the chorus shared by Earl McDonald (tenor jug) and Clifford Hayes (violin) and the double-time feel for violin solo into the final ensemble where everyone’s “heading for the barn,” all with complete control and relaxation. The coda is perfect with an open 13th between the two jugs. The lyrics for “Don’t Give the Lard Away” tell a humorous story with “Lard” having a decidedly double meaning. The verse comprises an unusual length of 24 bars to set up the story and the 16-bar chorus requires you to tap your feet, grin and laugh out loud at the line “He’s from the East, Save the grease!” This tempo would’ve had any dance floor, whether barn or ballroom, filled with high-steppers!

Hal, I’ll leap into the fray and open the discussion for the next two cuts. “Banjoeno” is a show-stopping tremolo banjo solo with both jugs and supporting banjos contributing a solid two-beat accompaniment. The first theme is a 32-bar tune in F with an interesting chord progression: F-Db7 (two-bars each for 2x); Dm (8 bars); Bbm6 (8 bars); F (4 bars), C7 (2 bars) and F (2 bars). We hear it twice and then through a stepwise chordal ascension (F to G to A7) arrive in the key of D for the real highlight of the track! While this is the same theme we’ve already heard, now we are treated to unaccompanied banjo trio and the recording is so good you can hear the fancy fingering from every string! It’s really beautiful.

They take it back from D to F with a smooth modulation (D, D7, G7, C7) and now Clifford Hayes picks up the spartan melody on violin, while the momentum builds on the final chorus with Lewis joining on sax and ensemble out. Contrasting this instrumental showpiece is a medium stomper with a ridiculous title: “Skip, Skat, Doodle-Do.” The band romps through this one with a nice steady wobble. A four-bar intro (the final four bars of the chorus) lead us into a verse in Gm. No words here and that’s fine as it’s nice to hear Lockwood’s alto play the verse and chorus melodies so prettily (while hot). For me, the highlights of this track are the ensembles following each vocal chorus. The feeling of cohesion they attain shows a group of musicians who’ve played together on many a gig! Hal, what stands out for you here and can you take us to the next tunes?

HS: I think the jug playing on “Florida Blues” is some of the best on any of these sides. “Don’t Give The Lard Away” gives us a chance to hear Lockwood Lewis’ engaging vocal style. And on “Banjoreno,” Cal Smith, Curtis Hayes and Freddie Smith were ACES! What a sound they got! Do you suppose the Western Swing banjo virtuoso Ocie Stockard had this record? “Skip, Skat, Doodle-Do” is a good novelty-type number along the lines of “Boodle-Am-Shake” and it gives us an opportunity to hear Earl McDonald sing a couple of choruses.

The last song recorded on Dec. 10 is “Louisville Stomp”—another original by Henry Clifford. It has a nice, rocking feel throughout. The ensemble plays a verse, followed by a chorus with an attractive melody featuring Clifford Hayes’ violin and the two jugs giving the effect of a pianist playing “boom-chuck” with the left hand. Lockwood Lewis’ solo includes a growl, which we usually associate with “novelty clarinet.” Cal Smith solos on tenor banjo on the final chorus, before the ensemble wraps up the performance. Henry Clifford and Earl McDonald certainly played some interesting lines on this one!

Jeff, the Dixieland Jug Blowers session on the following day (Dec. 11, 1926) featured one of the most iconic New Orleans jazzmen. Would you like to introduce the first song?

JB: Before I do, I have to say that I find “Louisville Stomp,” and this is a word I’d never suspect to use for a jug band, to be a poignant tune (!?!). What is it? The tempo? The plaintive violin sound Clifford Hayes achieves? The melody of the chorus? The almost vocal quality of our jug blowers? The fun they’re all having? It’s simply lovely; relaxed, warm and my favorite cut so far.

That is, until we move to Dec, 11! Our featured New Orleans legend is Johnny Dodds, which makes sense as there were few busier recording musicians in Chicago in 1926 than was he; he turns up on, and improves, almost everything it seems! Other than his addition the band personnel stays the same. “House Rent Rag” starts with three strikes of what sounds like a banjo head (though no tones, just the thumps) and then Earl McDonald intoning a parodic, quasi-religious speech that starts “High skirts and bootleggers.” About 48 seconds in, violin and banjo start to play underneath this hokum and we finally get to some hot music with only a minute and twenty seconds to the end of the cut. Is it worth sitting through all that came before it? YES! Johnny Dodds’ breaks alone makes you glad you stuck around. He knows he’s one of the best of the musicians in Chicago, let alone in this band, and he plays hot on this 16-bar sequence that sounds like everyone is riffing on the chorus to “At the Jazz Band Ball.” Hal, the side finishes with some heat, but hopefully there’ll be some more music in the next cuts?

HS: Remember the RCA “Vintage Series” LPs? I bought the Jugs, Washboards and Kazoos record just after it was released. I was enjoying the Dixieland Jug Blowers sides, the mock sermon and the first ensemble chorus…then this bolt of lightning came blazing out of the speaker: JOHNNY DODDS on clarinet! I don’t think I have ever recovered from hearing that break. Still my favorite by J.D.! Apparently, the recording director thought that the front line needed more firepower—so he hired Dodds to play clarinet on the second session. I thought the alto and violin were just fine, but who could object to the addition of the bluesiest of New Orleans clarinetists for the next four sides?!?

We should note that all the songs on the DJB session of Dec. 11 are credited to Henry Clifford, with Earl McDonald as co-composer on “House Rent” and Cal Smith is also listed on “Carpet Alley.” Let’s start with “Memphis Shake”…Johnny Dodds plays beautiful phrases over the alto and violin as the melody alternates between upward and downward chromatic runs. On subsequent choruses there are wonderful breaks by Dodds, Cal Smith and Lewis and then an interlude with banjo tremolos (Dodds in chalmeau register for four bars, then back to the joyous ensemble sound we love). The DJB returns to the primary melody, with a break by McDonald then plays the song out with a lazy, floating beat. Even the normally kinetic Johnny Dodds plays laid-back triplets over the double ending.

“Carpet Alley” once again puts the trio of banjoists in the spotlight, framed by Charleston beats and especially flatulent-sounding jugs. The second strain sounds a little bit like “Moonlight on the Ganges,” and leads into a stoptime with Dodds and Lewis trading phrases. There is a “modern” interlude that sounds as if it could have been arranged by Fletcher Henderson, then more of the second strain—this time with haunting breaks by Dodds and then the banjos to take it out. The DJB made a second take at a much brighter tempo. Dodds is more prominent in the recording mix—and that’s a good thing!

“Hen Party Blues” is similar in structure to the second strain of “Dallas Blues.” After the ensemble, Hayes plays a bluesy violin solo with banjos playing the afterbeat. Dodds is next, then there are stoptime choruses for Hayes, Dodds (sounding particularly inspired) and stoptimes for Lewis, the banjoists and McDonald, with some unusual rhythm underneath before the final ensemble. Once again, the second take was played at a brighter tempo. Clifford Hayes’s solo sounds like he was attempting to imitate a muted cornet. Dodds has another fantastic solo, followed by Hayes, then Dodds returns with a wild vibrato that leads into a blues-drenched chorus. The rest of the performance follows the same routine as on take – 1. Jeff, what are your thoughts on the final three numbers from this recording date?

“Hen Party Blues” is similar in structure to the second strain of “Dallas Blues.” After the ensemble, Hayes plays a bluesy violin solo with banjos playing the afterbeat. Dodds is next, then there are stoptime choruses for Hayes, Dodds (sounding particularly inspired) and stoptimes for Lewis, the banjoists and McDonald, with some unusual rhythm underneath before the final ensemble. Once again, the second take was played at a brighter tempo. Clifford Hayes’s solo sounds like he was attempting to imitate a muted cornet. Dodds has another fantastic solo, followed by Hayes, then Dodds returns with a wild vibrato that leads into a blues-drenched chorus. The rest of the performance follows the same routine as on take – 1. Jeff, what are your thoughts on the final three numbers from this recording date?

JB: I remember that LP! When I was in college, the music library had a great collection of jazz LPs and CDs bequeathed by an alum and ALL of those “Vintage Series” LPs were there on the shelves. I admit to skipping the one you mention (shame on me) but that makes this romp all the more delicious.

Again, I’m thrilled with the aural quality of these sides, Hal! You can hear every musician’s contribution; Earl McDonald plays some phrases that sound trombone-like to mix with the alto lead and the hot clarinet weaving! The first three-quarters of the 2nd strain of “Memphis Shake” sounds like the B strain of Charles L. Cooke’s 1914 piano rag, “Blame it on the Blues.” Also had the band yet heard Jelly Roll’s recording of “Black Bottom Stomp?” Only on the trio I hear Henry Clifford playing alternating 4’s and 2’s every four bars during the banjo solo, just like bassist John Lindsay accompanied Johnny St. Cyr solo chorus! Finally, do you think it was a shock receiving this tune with the flip side being “Doctor Jazz” by Morton as you pointed out earlier. I wonder how many purchasers loved both or gravitated to one over the other (I warrant that’d be a study for collectors of 78s to see which side was more worn; compared with some of the expensive research being done these days on goofy topics, I’m sure this could get HUGE funding…whoops, daydreaming again…LOL!)

What first struck me on “Carpet Alley Breakdown” was the intro where Henry Clifford’s jug sound is reminiscent of a bass sax! The band’s use of dynamics on the first strain is very effective as is the slower tempo of take 1. For me, that interlude you mentioned sounds more like Morton’s arranging to me; either way the entire track is beautiful: relaxed, charming and one I listened to about six times in a row. The best thing about take 2, excepting Dodds’ more prominent presence in the mix as you pointed out, is they modified the attempted one bar breaks between Dodds and Lewis to be two bar breaks after Lewis stepped on Dodds’ second one on take 1. Were they both released?

What first struck me on “Carpet Alley Breakdown” was the intro where Henry Clifford’s jug sound is reminiscent of a bass sax! The band’s use of dynamics on the first strain is very effective as is the slower tempo of take 1. For me, that interlude you mentioned sounds more like Morton’s arranging to me; either way the entire track is beautiful: relaxed, charming and one I listened to about six times in a row. The best thing about take 2, excepting Dodds’ more prominent presence in the mix as you pointed out, is they modified the attempted one bar breaks between Dodds and Lewis to be two bar breaks after Lewis stepped on Dodds’ second one on take 1. Were they both released?

“Hen Party Blues” is another winner. The harmonic sophistication of this blues belies the “rural” provenance of half of these instruments. These were REAL accomplished musicians choosing “folky” instruments for their performances. The final ensemble sounds like a three-horn front line with Dodd’s fluid clarinet, Lewis’ solid sax and McDonald’s trombone-like jug. I like both takes on this tune; the final ensemble on take 2 is perhaps a bit hotter.

Hal, we’ve space to introduce the band’s next recording date on June 6, 1927. There seem to be some big changes. Could you illuminate them, why you think they made those changes and take us through the first song as a teaser for next month’s follow-up?

HS: Take 2 of “Carpet Alley” was released on HMV in England, backed with take 1 of “Hen Party.”

After the December sessions by the Dixieland Jug Blowers, Victor offered another recording contract to Clifford Hayes. He accepted, though the band recorded with a different instrumentation and some new faces. Holdovers from the December session were Hayes, Lockwood Lewis, Cal Smith and Earl McDonald. The newcomers were: Hense Grundy, trombone; George Allen, soprano and alto sax; Dan Briscoe (alternating with Johnny Gatewood), piano; Elizabeth Washington, vocals; Prince LaVaughn, vocals. As before, the group recorded in Chicago (though not at the Webster Hotel). June 6 and 7, 1927 were the dates and the first song recorded was, not surprisingly, a Clifford Hayes original: “National Blues.”

The performance begins in the key of Bb with Dan Briscoe playing a novelty piano phrase then a rather disorganized-sounding ensemble plays a chorus, then Lewis, Hayes and Briscoe solo. After a key change to Eb, Hayes fiddles two more choruses, followed by the two saxes riffing (backed by Grundy) and an ensemble chorus out with a coda featuring Grundy using a plunger mute. The combination of country fiddle, crude sax and trombone playing and the pronounced afterbeat in the rhythm section is reminiscent of early sides by Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys. Interestingly, “National Blues” was arranged by either Robin Wetterau or Charles Sonnanstine for the Great Pacific Jazz Band in the late 1950s. The arrangement wound up in the library of Ted Shafer’s Jelly Roll Jazz Band and they recorded it in 1965. The JRJB recording is excellent, with great solos by clarinetist Mike Baird and pianist Dick Shooshan!

Ron Geesin, in the liner notes to the Frog Louisville Stomp CD, mentions that “[Clifford Hayes’] aspirations were towards more sophisticated instrumental combinations, demonstrated in his later Louisville Stompers recordings.” The June, 1927 sessions—despite the old-timey front line sound—did point the way towards jazz, rather than countrified music. And a subsequent recording by Clifford Hayes would feature yet another renowned jazzman. Jeff, let’s save that discussion for part two.

JB: Can’t wait, Hal! Thank you for introducing us to this great group!

Jeff Barnhart is an internationally renowned pianist, vocalist, arranger, bandleader, recording artist, ASCAP composer, educator and entertainer. Visit him online atwww.jeffbarnhart.com. Email: Mysticrag@aol.com

Hal Smith is an Arkansas-based drummer and writer. He leads the El Dorado Jazz Band and the

Mortonia Seven and works with a variety of jazz and swing bands. Visit him online at

halsmithmusic.com