The all-female Big Band of Ada Leonard (see Part 1) was the best-known of around 100 “all-girl” Swing orchestras playing for the troops during WWII. The Sharon Rogers Band toured overseas entertaining troops in the Pacific war zone. Keen curiosity has arisen about these so-called “all-girl” orchestras of the war era.

The all-female Big Band of Ada Leonard (see Part 1) was the best-known of around 100 “all-girl” Swing orchestras playing for the troops during WWII. The Sharon Rogers Band toured overseas entertaining troops in the Pacific war zone. Keen curiosity has arisen about these so-called “all-girl” orchestras of the war era.

The following narrative relies in large part on the landmark research collated in the books Swing Shift: ‘All-Girl’ Bands of the 1940s by Sherrie Tucker (Duke, 2000) and The Sharon Rogers Band by Pat McGrath Avery (self-published, 2010). Please note that the term “girl,” meaning “woman,” is used in its historical context. Nevertheless, these ensembles were often staffed by very young woman, often less than 18 years of age as explained below.

Becoming a National Act

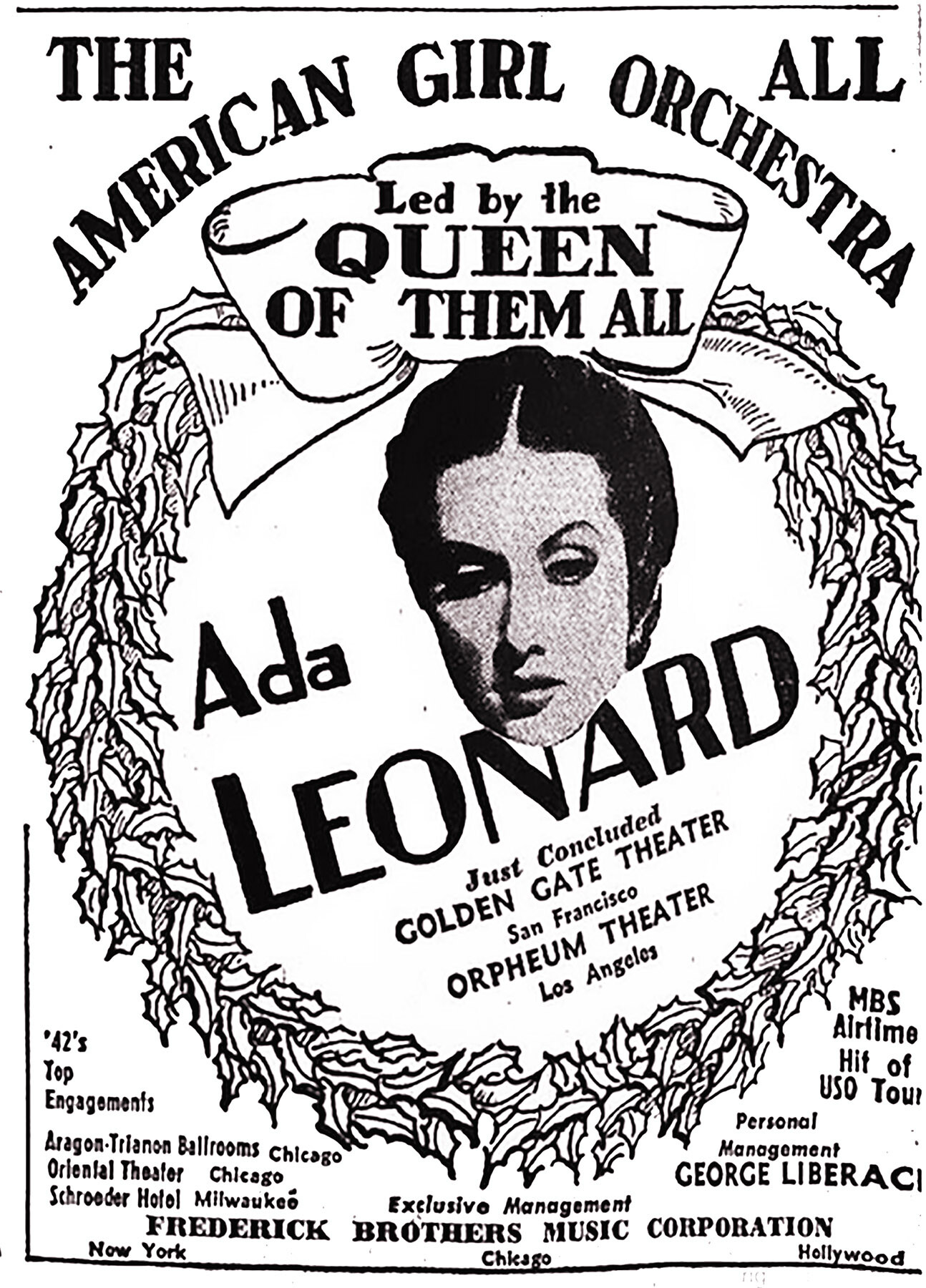

Ada Leonard (7.22.15 – 11.29.97) and the All-American Girl Orchestra toured Army training camps, USO theaters and commercial dance halls across the USA during the war and were second in popularity only to the International Sweethearts of Rhythm (profiled in part three). The bandleader split their performing schedule between army camp gigs during the week and theaters or dance halls on the weekends, dealing with USO as just another client though a large and important one.

By 1944 about 80% of Leonard’s personnel had turned over to a new and younger crew. The orchestra had more professional representation from the Frederick Brothers Agency who booked Ina Rae Hutton and other all-female bands as they toured across the nation appearing at increasingly prominent ballroom and theater venues: The Trianon (Chicago), Paramount (Des Moines), The Orpheum (Hannibal, MO and Los Angeles, CA) and the Golden Gate Theater (San Francisco, CA).

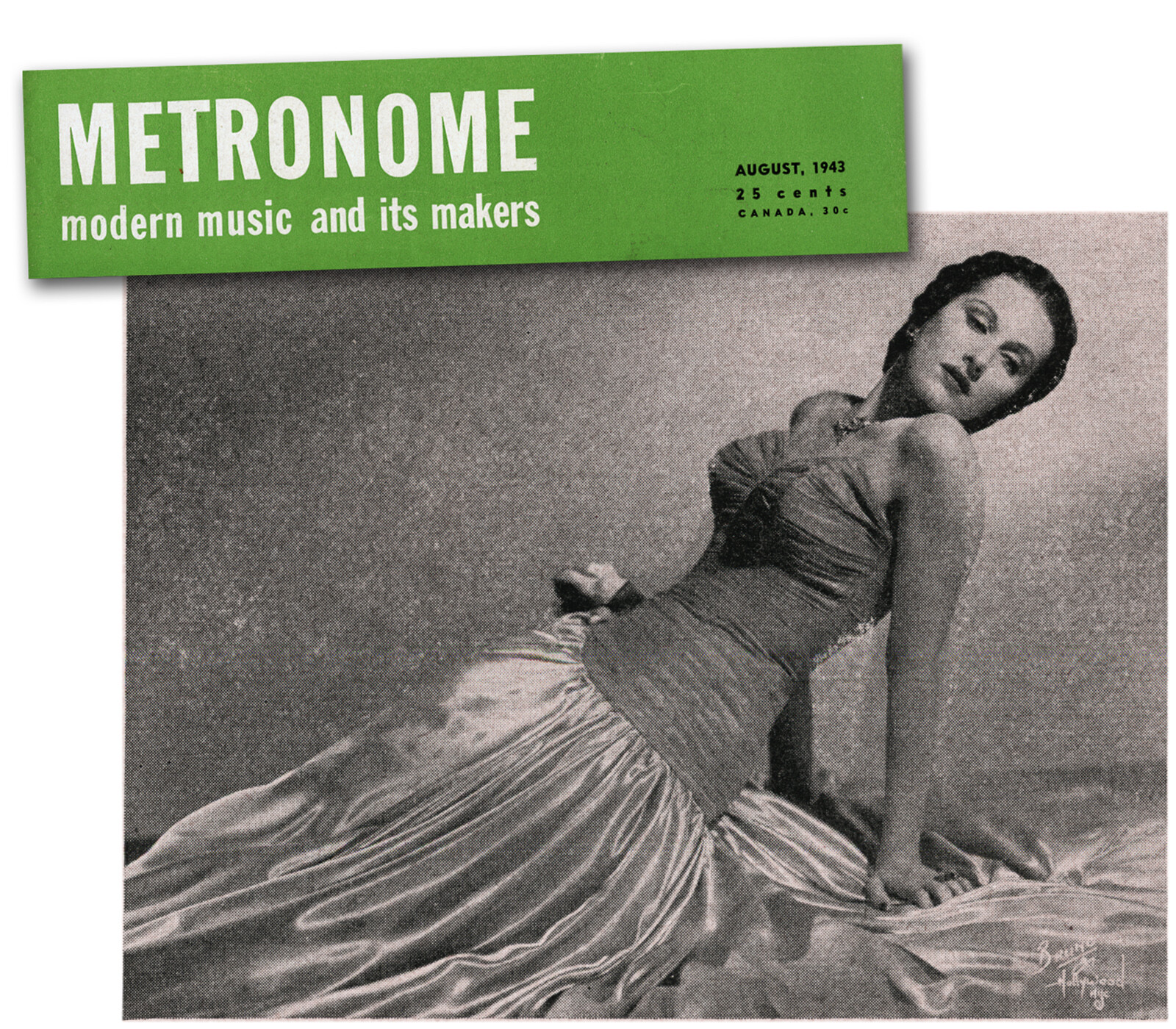

Despite the rose-tinted reminiscences of Leonard’s former associates, a Metronome magazine review of her show at Lowe’s State, New York City on July 15, 1943 reveals that she keenly understood her audience. Ada teased, titillated and toyed with her mostly-male fans taking multiple costume changes.

Her gowns were voluminous but “thoughtfully dropped away and slit in the right places,” according to the Metronome reviewer:

“This Leonard girl is a neat dish and doesn’t need a band to make her an attraction. All she needs is to slink around the stage in a discreetly suggestive manner, as she does very effectively.

Her dancing is burlesque-ish but intriguing, as some of her baton twirling is also. She helps move the baton through uncharted channels with somewhat more than arm and wrist movements to the great delight of the male audience.”

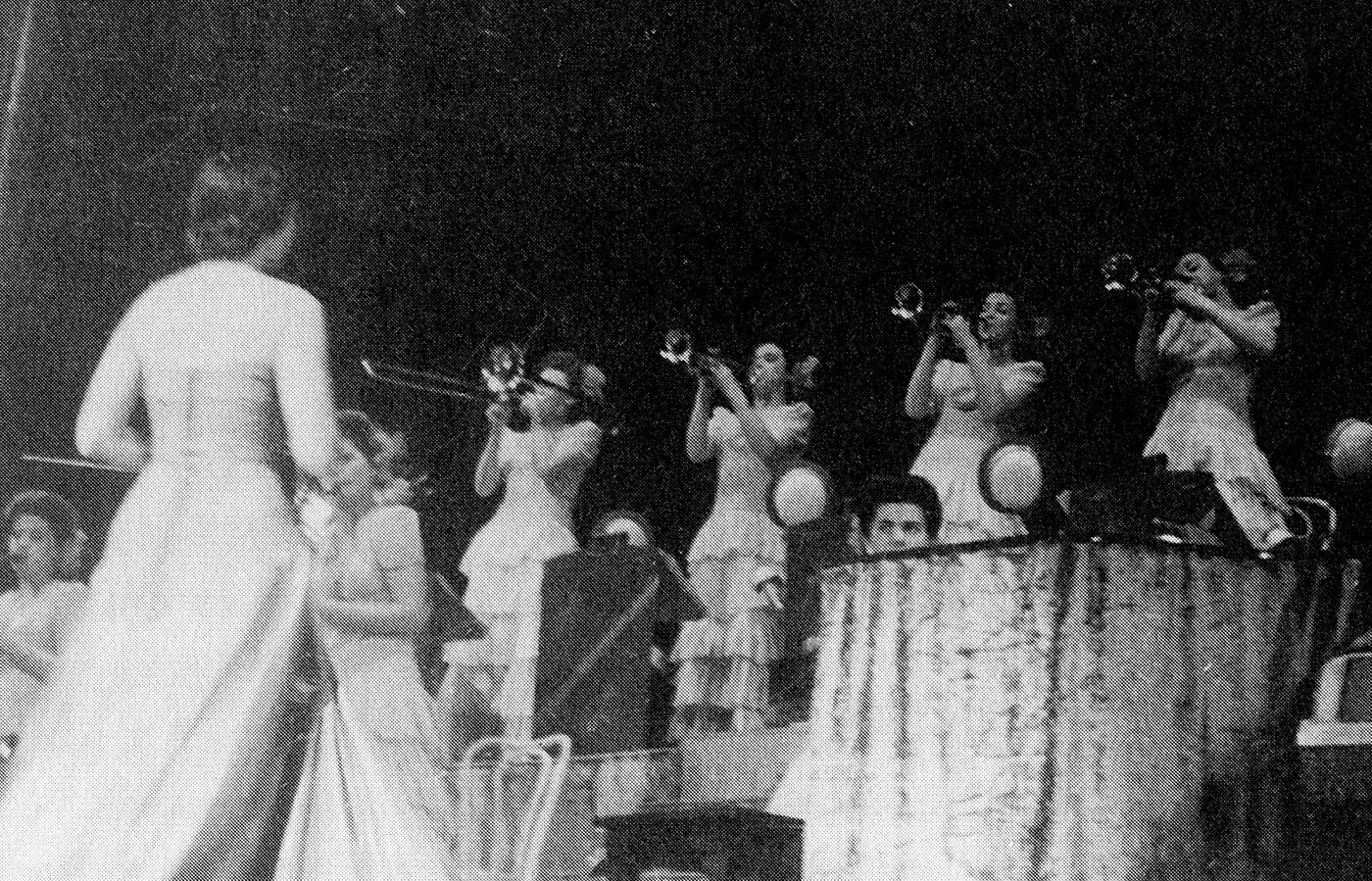

The ‘All-Girl’ Orchestra Jumps

Alto sax player Betty Kidwell told Sherrie Tucker that between 1943 and ‘46 Leonard’s orchestra was “jumping” developing into a hot Swing ensemble with solo improvising and good arranging. Leonard felt that her audiences were now willing to accept “hard swinging jazz” from women so long as a glamorous and feminine image prevailed.

They were receiving encouragement and validation from their male peers. Count Basie and Lionel Hampton loaned arrangements. Joining her staff was the famed arranger Gene Gifford (1908-1970) who had been a significant force in building the Casa Loma Orchestra at the dawn of Swing.

Kidwell told Sherrie Tucker that the Gene Gifford arrangements “made our four saxes sound like five or six.” Saxist Betty Rosner said that the Gifford charts were her main reason for turning down an offer from bandleader Claude Thornhill.

Kidwell told Sherrie Tucker that the Gene Gifford arrangements “made our four saxes sound like five or six.” Saxist Betty Rosner said that the Gifford charts were her main reason for turning down an offer from bandleader Claude Thornhill.

By late in the war, conditions and circumstances had improved for female musicians regarding sexual harassment, USO logistics and job stability suggests Tucker, “Veterans of the all-girl band business tended to be bitter, having been stranded and shortchanged far too many times.”

Unfortunately, there is sparse documentation of the later ensembles. Leonard told Tucker in the 1990s that this “young band” was her favorite, keeping a large blow-up photo of it in her living room:

“They were just wonderful. I had a great deal of pleasure with them because they were ambitious, and they loved to play. They had not been through what the older girls had been through.”

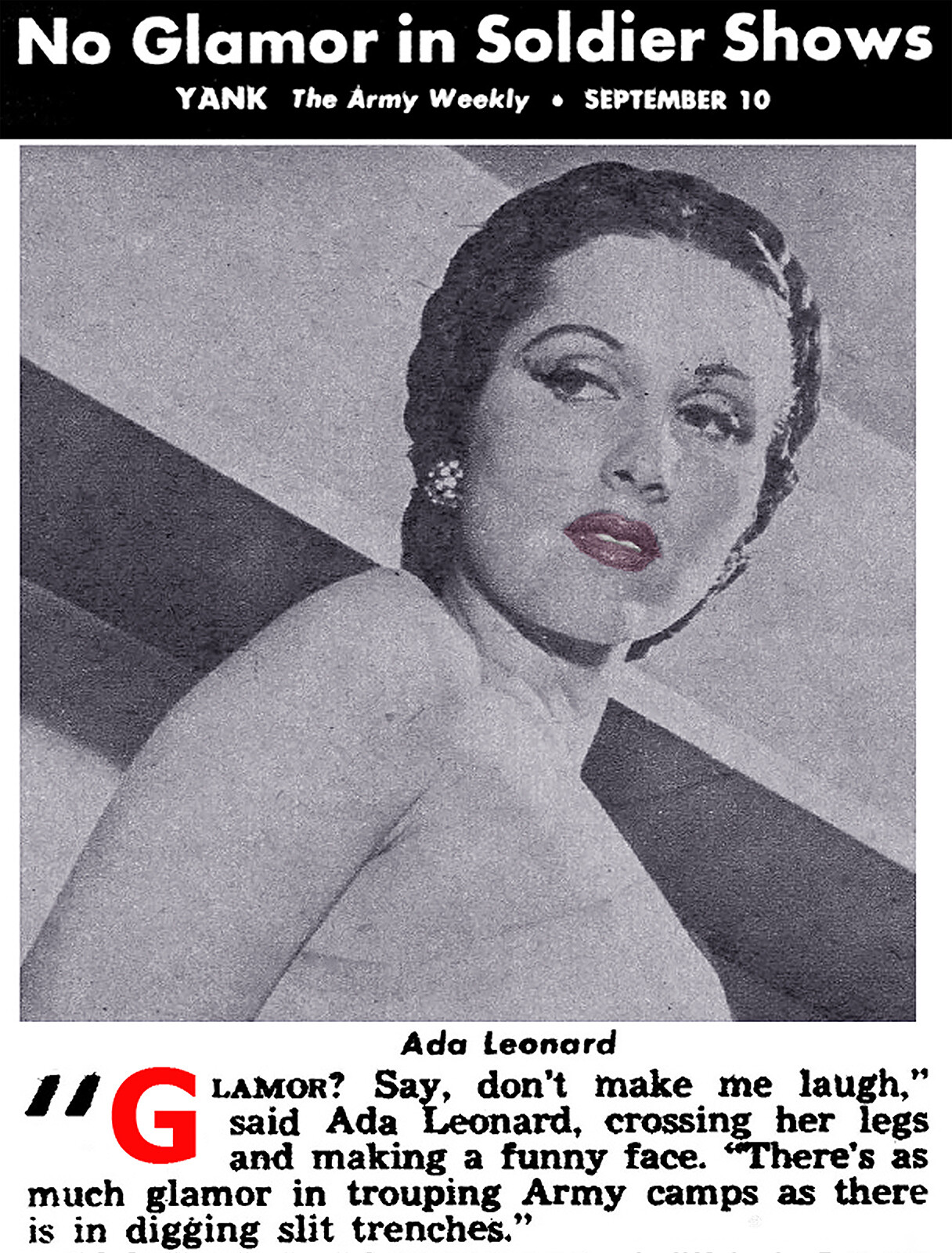

A column profiling Leonard appeared in YANK: The Army Weekly in September 1944. It noted that her childhood in Oklahoma had included old-time vaudeville. Her mother and father were show-business troupers who put Ada on stage at age three and she was a professional by age eleven. The article offered little else of substance, except that the reporter caught her road-weary tone.

Other Ada Leonard Orchestras, 1946-55

For almost a decade after the war Leonard presented all-women ensembles, running a small “society orchestra” for a while. But booking female bands gradually became an impossible proposition.

Ada told Sherrie Tucker that in her final venture she wanted to craft an orchestra of men which would be judged on its own merits and not hired “because of their looks or sex appeal, but because they are good musicians.” That all-male band appeared under her leadership on television station KTTV Channel 11 in Los Angeles during 1953-55 and she considered it the best at playing her book of arrangements.

Sadly, throughout the mid-Twentieth Century, female musicians and all-women bands faced harsh prejudice and sexism. For example, Leonard was once hired to make a Universal Films short, but after filming male musicians were dubbed over the footage of her group. Gender discrimination by record companies, union officials, the music press, club owners and male musicians was at least as bad as racial segregation had once been.

After three decades in show business, half of it slinging a baton, Ada Leonard retired from professional music in 1955. Reading between the lines, it was the disrespect, ridicule and especially the unrelenting sexual harassment that ultimately provoked her retirement, leaving a bitter taste:

“I had burnout about three times. I quit. I just walked. I couldn’t take it. And the best band that I had, I disbanded because I couldn’t do it anymore . . . Who needs it.”

The Sharon Rogers Band, 1940-47

Above all else, members of The Sharon Rogers Band were united in their mission to bring hope, solace and an image of femininity to the troops. They performed for six months in the Philippines, Japanese and Korean war zones in 1945-46 for more than 100,000 troops. They saw evidence of war “horrors,” visited Hiroshima after the atomic bombing, broadcast on Armed Forces Radio from Osaka and survived an airplane crash at sea without serious injury.

The 12-piece band aimed for a sound roughly equivalent to “a Glenn Miller or Harry James” consisting of four saxes, three trumpets, one trombone, piano, bass, drums and a vocalist. There is no surviving audio of the band available.

The musicians were bound together in a sisterhood by their overseas experience, convening regularly into the 2000s. A book by Pat McGrath Avery celebrates and documents their service, pluck and sustained spirit, The Sharon Rogers Band (self-published, 2010). That and Sherrie Tucker’s Swing Shift (Duke University, 2000) are the main sources for the following narrative.

From North Chicago to Coney Island and the ‘Foxhole Circuit’

Emerging from Chicago-area women’s ensembles, the original members of the band were all graduates of Northside Chicago high schools and from a closely-knit community of families. Coalescing as the Melody Maids around 1940 (not to be confused with the 1933 Melody Maids) they were fronted for a while by a male bandleader and business manager, Carl Schreiber.

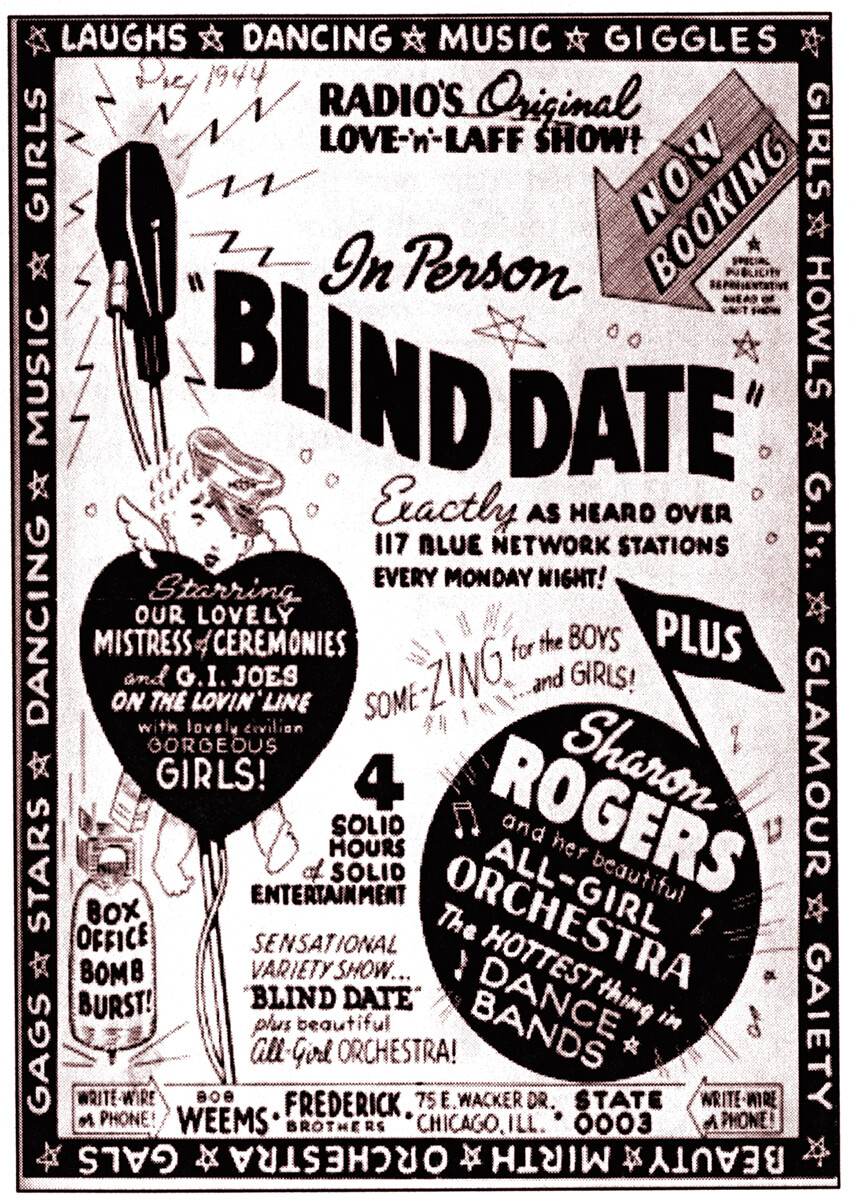

Getting a gig at the Avalon Ballroom in Chicago they became members of the American Federation of Musicians, Local 10. Before joining the USO, they toured the Midwestern region, once playing opposite Jimmy Dorsey, and were soon gigging across the Eastern half of the United States, garnering wide broadcast exposure on the Blue Radio Network.

Touring widely before 1945 the Sharon Rogers Band took on a vigorous schedule of commercial dance halls, theaters, nightclubs, roller rinks, Stage Door Canteens and radio broadcasts. They also performed one-off shows at army training camps as they segued onto the USO stage.

Their greatest early commercial success was a steady job at the Coney Island Amusement Park in New York City. That’s where they were approached in late 1944 and recruited to entertain the troops overseas.

Bass player Sharon “Sherry” Rogers was chosen as leader somewhat arbitrarily, possibly because she stood in front of the band on stage. From there she had eye contact with all the members and was close to the announcing microphone. Or maybe it was her personality and leadership skills.

Tenor saxophonist Laura Daniels told Sherrie Tucker, “She really knew how to handle those men,” meaning certain commissioned officers who acted aggressively or were abusive. In any case, it was a collective decision since the band was run as a co-op.

Though the term sexual harassment was not known at the time, author Sherrie Tucker writes, “the Sharon Rogers musicians have come to see themselves as women who experienced sexual harassment – and who fought it . . . professionals experienced in recognizing and fighting unfair labor practices.” They paired up in a buddy system to stay safe and when touring overseas the US Army posted armed guards outside their sleeping quarters to prevent rapes.

Even before Pearl Harbor, the United Service Organizations (USO) had been spearheaded by singer Al Jolson. It was an ecumenical coalition of six community-based volunteer organizations: The Salvation Army, YMCA, YWCA, the Jewish Welfare Board, the National Catholic organization and the Travelers’ Aid Association.

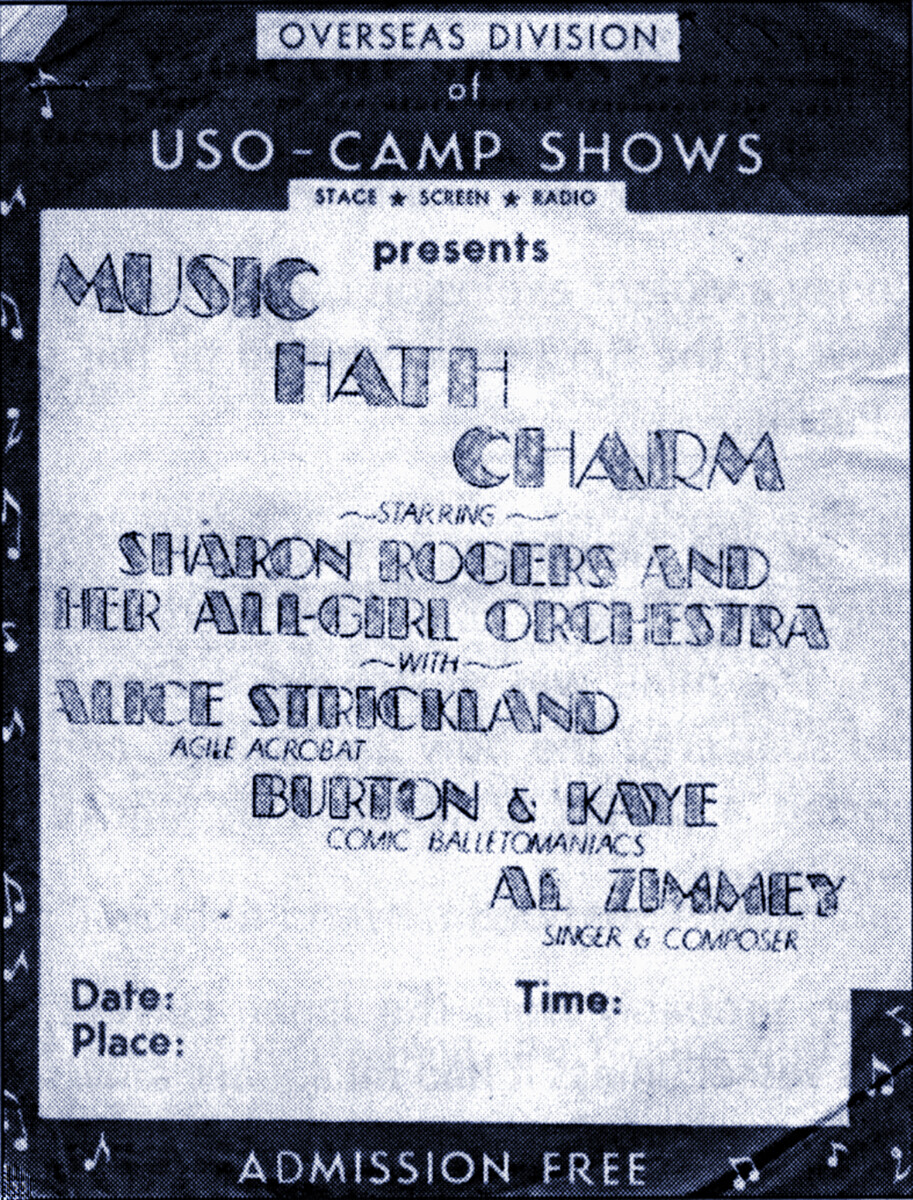

Between 1941 and 1947 the USO presented more than 7000 entertainers overseas at 428,000 performances. Whereas Ada Leonard’s orchestra had been designated USO-Show Unit #9 in 1941, The Sharon Rogers Band was Unit #687 reflecting the explosive growth of the semi-government organization.

Rules for the overseas ‘Foxhole Circuit’ were generally similar to the domestic army camp ‘Victory Circuit.’ But musicians were civilians traveling with military detachments in war zones. Strict security and censorship concerns were reflected in the stern Dear Entertainer letter and “WARNING” received by all performers:

“. . . you must submit every bit of your material and action in writing to our script department . . . subject to RIGID INSPECTION . . . A copy of your approved script will be furnished to you; and you will then be compelled to adhere to this finally okayed and accepted script in the strictest form. . .

This finally okayed script will be sent ahead of you to every base at which you will appear, and if the slightest deviation is made from same, you will immediately be dismissed without notice and summarily returned to the US and marked ineligible for any future engagements from Camp Shows.”

The Sharon Rogers Show and Personnel

In June 1945 they gave a USO-sponsored performance in Brooklyn for a maritime service of 2000 men. It’s probably representative of their USO-approved show.

The program opened with their theme song, “A Pretty Girl is Like a Melody” followed by “Back Beat Boogie” and “Song of the Volga Boatmen.” A vocalist sang “Embraceable You” and “Sentimental Journey” followed by a band novelty, “One Meat Ball.” Master of ceremonies, Al Zimmey sang “Give my Regards to Broadway” and a couple others. There was also a dance team and baton act with college songs.

Vocalist Jackie Weber was “cute, young and full of life” with “a flair for modern ballads.” Instrumentalists included trumpeter Florence “Flo” Sheffe, who had shared a stage with The Mills Brothers and Chico Marx. Roberta “Bobbie” Taliaffero “played a mean trumpet . . . GIs went wild every time she played” and her specialty was performing “Sugar Blues” in the Clyde McCoy manner.

Trombone player Lois Heise joined the Melody Maids at age 14 and had worked in the USO band of Betty McGuire. Saxophonist Laura Daniels began playing music at age 12 performing in Northwestern Chicago dance bands and was added shortly before the overseas tour. Greta Jean Bogan was an “excellent” drummer. Nicknamed “Gee Jay,” her peers thought her a “vivacious, worldly wise divorcee.”

But, she’d pulled a fast one on the band and Uncle Sam. Bogan was only 16 and had forged her birth certificate. Bandleader Rogers had to do some fast talking to prevent the USO from sending them all home. So indeed, many of these “all-girl” bands often consisted of very young women and girls.

Piano player Shirley Goldberg Moss was considered “a genius” by her band mates. But she fell ill on tour in The Philippines and was replaced by Charlotte Horowitz Murphy. Older and more experienced, “Charlotte would head for the nearest USO and sit at the piano, playing requests that would lead to lengthy sing-along sessions.”

The professional dance team of Rose Marie Scharf and Julieanne Holton joined the troupe in Manila. Holton had started on the USO circuit at age 16. When the show they were traveling with was cancelled in the Philippines they were placed with The Sharon Rogers unit.

The Sharon Rogers Show also offered Variety acts including the married couple of Howard and Wanda Bell: “They were an acrobatic team. He’d stand on a roller on balls. She’d . . . put her head on his and do all kinds of acrobatic moves.”

Touring The Philippines, Japan and Korea

From July 1945 to January 1946, a hectic itinerary took Unit # 687 through The Philippines, Japan and Korea. Starting near Manila they performed at stadiums, hospitals, air fields and Army depots visiting army divisions, the Signal Corps, Field Artillery, Far Eastern Air Service Command, the Engineers and the Seabees. Fighting was still going on: 100,000 died during their stay and the stench of mass graves was unavoidable.

On the Japan-Korea leg of the tour they played 63 shows and two AFRS radio broadcasts in 44 days, while traveling 17 days with only 2 days off. Venues in Japan ranged from a famous opera house to recreation halls, depots and air fields, for a total attendance of 99,400.

Military brass and political leadership strove mightily to keep their traveling entertainers safe. But America was engaged in an existential struggle spanning a Pacific Ocean battle zone covering 1/3 the surface of the globe. Accidents happened. Altogether, twenty-eight USO entertainers died overseas, mostly in airplane crashes.

Air Crash at Sea and Return Home

On Jan 22, 1946 returning to Japan from Korea, the two-engine C-47 aircraft transporting them hit bad weather and crashed, ‘ditching’ in Shimonoseki Strait just off the Southern tip of Kyushu Island. The water landing was “smooth,” if traumatic. Luckily, they were quickly rescued by local fishermen before the plane sank in twelve minutes.

The musicians took it all in stride as just another chapter in a great adventure worth writing home about, as Laura Daniels did:

“Lois is much better now. Her eye sure got banged up. She was very nervous and suffering from shock for several days. Gee Jay pulled several muscles in her leg and has her knee in splints (however the newspaper exaggerated greatly – nothing broken). The rest of us are fine – which is a miracle when I think of it.”

After a brief hospitalization they returned to America by ship in late-January 1946. For dancers Scharf and Holton, it was their second air crash, yet one of them wrote “I wouldn’t have missed the trip for the world.”

In a glowing post-action report Liaison Officer, First Lieutenant Harold W. Peterson commended the performers:

“During the USO Unit #687 tour of Japan and Korea many hardships were encountered such as living conditions, travel facilities, food, climatic conditions and the likes. In one instance we lived on a train for eleven days, using an attached baggage car as our kitchen supplemented with 10-1 rations, but even under these conditions the unit never missed putting on a performance that was scheduled for them, nor was there any dissention or griping . . .

Besides the favorable commendation given by the [Commanding Officer] of every installation that the unit performed at, personal commendations were given to the unit while in Korea by Under Secretary of War Patterson and General Medges.”

They Laughed, Cried, Crashed and Almost Died Together

Back in the USA, several in the band wanted to ‘re-up’ and take the ride again. But not all. Soon, The Sharon Rogers Band was unable to compete with returning male musicians, disbanding in February 1947. For a while, Rogers had a combo in Chicago with trumpeter Bobbie Tallieferro and drummer Gee Jay Bogan.

Dancers Holton and Scharf signed up for more overseas duty, touring with the USO shows Hotshot Follies (Germany 1946) and Pardon Me (Philippines 1947). Rose Marie Scharf, a first-generation German-American, departed to entertain troops in Europe on the ocean liner George Washington, the very ship on which her immigrant parents had arrived in America before she was born.

The Sharon Rogers Band by Patricia McGrath Avery is a labor of love. It’s assembled like a scrapbook with plentifully reproduced, clippings, ephemera and letters home conveying the action in granular detail. Appendences contain USO documents, a detailed itinerary and bibliography, but the book lacks an index and the photos are poorly reproduced.

One of the musicians later wrote a song lyric about their experiences set to the melody of “Ragtime Cowboy Joe.” It’s quoted in Swing Shift and provided the subtitle for Pat Avery’s book:

“They laughed together, cried together, crashed and almost died together

Listen to the rhythm, talk about your rhythm, Sharon Rogers Band!”

Part three will feature the International Sweethearts of Rhythm who toured Europe and Germany during the U.S. Occupation of Germany.

Side Bar

Touring widely before 1945 the Sharon Rogers Band took on a vigorous schedule of commercial dance halls, theaters, nightclubs, and radio broadcasts. They also performed one-off shows at army training camps as they segued onto the USO stage.

In an overseas tour sponsored by the USO-Shows the all-female Sharon Rogers Band performed for six months in the Philippines, Japanese and Korean war zones in 1945-46.

As recorded by the Andrews Sisters, the song “Three Little Sisters” has a lovely resonance with their story. All the musicians were recent graduates of North Chicago High Schools and a community of close-knit families. The song, written by Irving Taylor and Vic Mizzy, includes the line “each one was only in her teens.” The phrase “tell it to the marines” was sarcasm meaning, “I don’t believe you.”

This slideshow features most of the available photos of the Sharon Rogers band, with images of Ada Leonard, Rita Rio and others.

Links:

Jazz Rhythm – Ada Leonard page

Jazz Rhythm – Sharon Rogers Band page

Ada Leonard – slideshow

Dynamic Women of Early Jazz and Classic Blues, Pt 1

Dynamic Women of Early Jazz and Classic Blues, Pt 2

Women of Jazz – five radio programs

Books:

Swing Shift: ‘All-Girl’ Bands of the 1940s, Sherrie Tucker, Duke University Press, 2000

Swing Shift on Google Books

The Sharon Rogers Band, Pat McGrath Avery, self-published, 2010

Periodicals:

Metronome, 1943

YANK: The Army Weekly, Sept. 10, 1944

Dave Radlauer is a six-time award-winning radio broadcaster presenting early Jazz since 1982. His vast JAZZ RHYTHM website is a compendium of early jazz history and photos with some 500 hours of exclusive music, broadcasts, interviews and audio rarities.

Radlauer is focused on telling the story of San Francisco Bay Area Revival Jazz. Preserving the memory of local legends, he is compiling, digitizing, interpreting and publishing their personal libraries of music, images, papers and ephemera to be conserved in the Dave Radlauer Jazz Collection at the Stanford University Library archives.