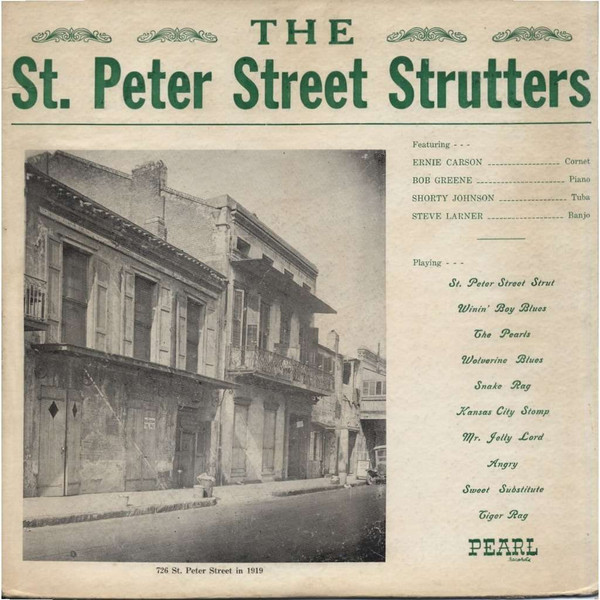

Hal Smith: Dear Readers, this month Jeff and I will explore the music of the great jazz pianist Bob Greene. We start with the first recording of his that I heard… In the mid-1960s, the old Jazzologist magazine published a rave review of an album by the St. Peter Street Strutters, singling out the Jelly-style piano playing of Bob Greene. Not long after reading the review, I found a copy of the LP at Ray Avery’s Rare Records in Glendale, California. Bob Greene’s piano playing was just as excellent as the review indicated!

Jeff, would you agree that this performance is a great introduction to Bob Greene’s music?

Jeff Barnhart: Absolutely, Hal! I listened to this track three times to absorb the details. “St. Peter Street Strut” by this eponymous ensemble is a haunting 32-bar AABA number. First, we’re treated to a solo piano chorus by Greene in what Morton called the “Spanish Tinge” (or habanera rhythm) with Shorty Johnson lightly accompanying on tuba. While banjo is listed on the front of the LP, I hear drums, but my ears were glued to Greene’s “Mortonisms”: the push-pull of the beat in the right hand; the laconic single-note melody of the bridge—and the moving left hand bass bringing us out of it; the grace note flourishes accomplished by sliding the fingers off a black note to the higher white note: all of these and more show that Greene had deeply quaffed from the Morton well.

The second chorus features a two-beat stomping feel and the entrance of one of my favorite cornetists, Ernie Carson. Carson rarely visited the high register of the horn, concentrating more on hot phrasing and bending notes in the middle range, a practice that leant his playing a distinctively singing (in terms of the human voice) effect. In this second chorus featuring Carson, Greene simplifies his accompaniment until the bridge, where he supplies some lovely polyrhythms coming back into the final eight bars (note as well how Johnson goes to four-beat during the first four bars of each bridge (B section). Greene provides a fuller accompaniment during the third chorus (Carson’s second solo chorus) and utilizes an idiomatic right-hand tremolo during the first half of the bridge. The first half of the final chorus is back to Greene, with some suspenseful pauses featured throughout, then Carson blares back in and takes us out.

Some final notes: Carson is a great choice here as he reminds one of George Mitchell, who recorded so many seminal sides with Morton in 1926; the tempo does speed up a bit from start to finish, but Morton habitually did that, especially during his solo recordings, so it didn’t bother me at all. Finally, a few questions you’ll be able to answer, Hal: who wrote this piece? Is the entire album comprised of this quartet or are there other combinations? WAS there a drummer on this album? My one rhetorical question: why hasn’t this tune become standard repertoire for bands including (or devoted to) the Morton style?

HS: Great observations, Jeff! According to the liner notes, the “drummer” is actually a drumstick taped to Bob Greene’s left foot! And Steve Larner plays banjo on some tracks, but not this one. The composer is listed as “traditional,” but I’ll bet it was written by Greene. By the way, the late Allan Jaffe encouraged this combination to record, and he offered the use of Preservation Hall for the session, on Dec. 30, 1964.

Before we move on to the next track, let me share some biographical information on Mr. Greene…He was born in New York in 1922; graduated from Columbia University in 1943 (Master of Fine Arts). He wrote documentaries for radio and television (including the Voice of America) taught from 1954 to 1962 at Columbia in the Dramatic Arts Department and became a speechwriter for Lyndon Johnson. He was going to join the campaign for Robert F. Kennedy, Sr., but he left that vocation after the tragic Kennedy assassination in 1968.

After hearing Jelly Roll Morton’s recordings in the 1940s, Morton became Greene’s greatest musical inspiration. Though he was not pursuing music as a career, by 1950 he was playing and recording with veteran musicians like Danny Barker, Pops Foster, and Freddie Moore. On his first recording (with Conrad Janis’ band) you hear just how much Morton influenced Greene’s playing on “Kansas City Stomp.”

JB: This is a markedly different feel from Morton’s original, but who can argue with the amazing rhythm section here? Barker and Foster bring authenticity to the proceedings, as does our subject, Bob Greene, who really was a disciple of Jelly. Greene plays full ensemble piano behind the opening ensembles on the A strain and contributes some syncopated rhythmic bass lines to his solo on the repeat of the B section, complete with a surprise banjo break! After a band “raspberry” ending Bob’s solo on B, we’re treated to more piano on the return of A. Solid playing on this section! The band takes a ride on two C sections, both with the customary four-bar alternations between “organ tone” chords from the horns and loose ensemble. The third time through C is freewheeling polyphony all the way, and the fourth time has a surprise habanera feel! Once more through the C section and out, sans the expected double ending, with Greene romping all the way! Where do we go now, Hal?

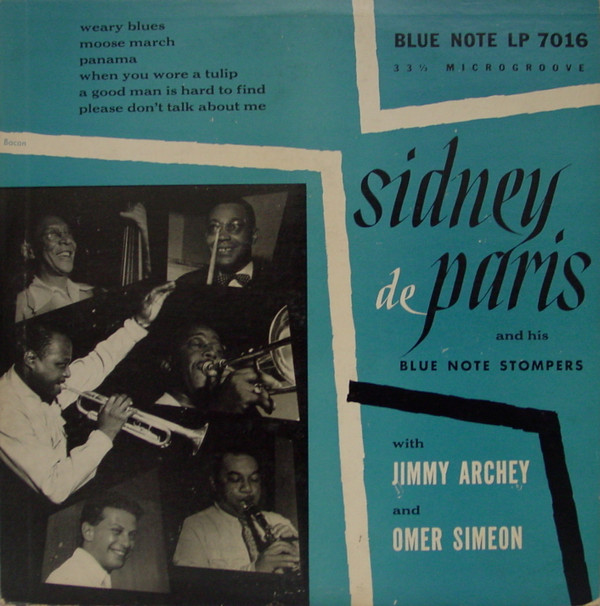

HS: We’re moving forward one year to a recording session with Sidney DeParis’ Blue Note Stompers; a traditional style band that predates the DeParis Brothers band. Pops Foster is back on string bass, along with Morton’s favorite clarinetist Omer Simeon, trombonist Jimmy Archey, the fine drummer Joseph Smith, DeParis on trumpet and Greene. On “When You Wore a Tulip,” you can certainly hear the Morton references in the piano solo but, interestingly, Bob Greene chose not to use some of the most well-known Morton phrases and rhythms.

JB: Seems the piano is even harder to hear on this one during the ensembles than on the Janis side, but if you listen closely during Archey’s trombone solo you can hear Greene stomping along. For me, Hal it’s refreshing that in his solo Greene didn’t revert to the (sometimes) over-used Mortonian figures favored by pianists (admittedly including myself) when playing in the style. Instead, he offers us some bonafide ragtime figures at the start of his ride, then heads into some riffing, replete with trills, a break featuring downward moving octaves in the left hand, more rhythmic figures in the right hand and a stomping conclusion. Speaking from a pianist’s point of view, not much “Mortonesque” was happening on this side from this band, despite the inclusion of Simeon, so I believe Greene simply adapted to the sounds around him. It’s a bit more pounding than what I’ve heard so far, so he might also have been concerned that any subtlety might be lost on both the band and the recording engineer for this date. Greene seems to have found his footing on the next side, “Weary Blues,” as his solo is much more inventive and more in keeping with the House of Morton.

JB: Seems the piano is even harder to hear on this one during the ensembles than on the Janis side, but if you listen closely during Archey’s trombone solo you can hear Greene stomping along. For me, Hal it’s refreshing that in his solo Greene didn’t revert to the (sometimes) over-used Mortonian figures favored by pianists (admittedly including myself) when playing in the style. Instead, he offers us some bonafide ragtime figures at the start of his ride, then heads into some riffing, replete with trills, a break featuring downward moving octaves in the left hand, more rhythmic figures in the right hand and a stomping conclusion. Speaking from a pianist’s point of view, not much “Mortonesque” was happening on this side from this band, despite the inclusion of Simeon, so I believe Greene simply adapted to the sounds around him. It’s a bit more pounding than what I’ve heard so far, so he might also have been concerned that any subtlety might be lost on both the band and the recording engineer for this date. Greene seems to have found his footing on the next side, “Weary Blues,” as his solo is much more inventive and more in keeping with the House of Morton.

HS: Let’s post the DeParis recording of “Weary Blues” and “Tulip” for the online version of this article and let the readers/listeners decide which piano solo best represents the style! On to 1958; a very unusual recording session featuring songwriter Shel Silverstein with the Red Onion Jazz Band. Silverstein was best known for writing “A Boy Named Sue”—one of Johnny Cash’s mega-hits. As a vocalist, Silverstein apparently didn’t care whether the key signatures were in his vocal range or not. Many of the vocals are atonal shouting! At least all the musicians in the ROJB had a chance to shine on the various tracks—even if it was only for a few bars. In the case of “Ragged But Right,” the horns took a break and let the rhythm section accompany the R-rated shouting. In addition to Greene on piano, we hear Steve Larner (the banjoist on the St. Peter Street Strutters LP), trombonist Steve Knight on tuba and bandleader Bob Thompson on drums. In the solo passages, Greene plays some of the over-used Morton figures you referred to earlier (I LIKE those)! Besides the manic “singing,” what do you hear on this one, Jeff?

JB: I hear Greene manfully struggling against Shel Silverstein during the vocal, but the opening chorus features terrific barrelhouse-style piano, and although he channels Jelly Roll in spots, I don’t hear too many cliches here (which, for the record, I ALSO like, but try not to overuse in my playing). After the vocal (resembling what might occur if Tom Waits melded with Salvador Dali and let Charlie Weaver sit in, all—as YOU joked—accompanied by Morton from the 1938 Library of Congress Recordings!!!) Perhaps the most impressive thing about this recording is when Silverstein begins to talk over Greene’s solo between “vocal” outings but is then silenced by true artistry shine through I kept going back to Greene’s solo and think it’s some of the HOTTEST playing I’ve heard in years. Regarding Silverstein, his phrasing is terrific…why is he shouting all the time??

Hal, do you have something a bit more…er…sedate to share?

HS: Ha! How about a juxtaposition of Bix and King Oliver-style cornet playing, Big Jim Robinson, an idiosyncratic clarinet sound and terrific Morton-style piano, over the framework of “Heebie Jeebies?” Take a listen to Johnny Wiggs’ “Bucktown Shuffle”…

JB: Ahhhh…lovely. Clears the ears and the soul. I love the rhythmic figure Greene uses to finish every chorus (copped from “Mr. Jelly Lord”)! And HERE all the Mortonisms he includes in his solo have to be there or it would be criminal! Hal, the thing about clicking on one of the links is you get to hear MORE tracks from the same release if you scroll down. So, I just listened to “Right Now is the Right Time” as well and loved Wiggs muted solo as well as the terrific contribution by “Jelly Roll” Greene!! The front line has that iconic, relaxed New Orleans approach to solos and ensembles: not too many notes, and each chosen one in the perfect place. Only three people are listed on the front cover, but that sure sounds like Allan Jaffe on tuba to me. Would this have been the right era for that possibility? At any rate, the music on this release is like a Ramos Gin Fizz from Bar Tonique compared to the Voodoo Daiquiri from Lafitte’s I ingested on the Silverstein track. Now where ya gonna take me, big fella?

HS: That IS Allan Jaffe on tuba—actually, helicon—with Wiggs, Big Jim, Raymond Burke, Greene and a very young Yoichi Kimura on drums. The LP was recorded in 1965 and released as Johnny Wiggs at Preservation Hall. Later it was reissued as Economy Hall Breakdown under Jim Robinson’s name.

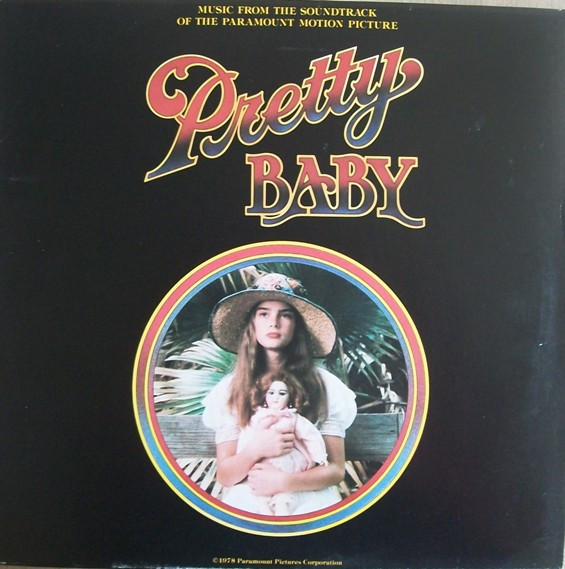

I wish I could take you to albums by “Bob Greene’s International New Orleans Jazz Band,” “Zutty and the Clarinet Kings,” two more volumes of the Carson-Greene St. Peter Street Strutters, the duet record with Don Ewell, the soundtrack to Louis Malle’s 1978 film Pretty Baby and The World of Jelly Roll Morton—a 1974 album for RCA featuring Greene’s touring band. Unfortunately, there are only a few random tracks from those albums available online.

There is a GHB CD by a later edition of the touring group that is posted on YouTube. Jeff, let’s hear your thoughts regarding “Buddy Bolden’s Blues” from this album.

JB: Hal, for me this is pure poetry; I’m really glad you chose this track. Greene’s pensive opening sets the tone, giving way to the dark, chalumeau register clarinetist Herb Hall utilizes stating the melody. This first chorus is a duo between them, Greene so gently backing the sobbing clarinet. Hall continues with a two-chorus solo that grows in intensity and volume. On the first clarinet solo chorus (John Williams’ bass now added), Greene begins by referencing the melody in his fuller accompaniment, then switches to chords held throughout their duration until the next harmony is reached (a technique that makes even Morton seem busy on his ballad playing). Marty Grosz whispers his entrance on guitar in the first half of Hall’s second solo chorus and the one and only Tommy Benford feathers in for the second half, while Greene begins to play melodic figures more forcefully, though never overpowering Hall. Marty’s chordal guitar solo is accompanied only by bass, which takes over the second half of the chorus accompanied by Bob Greene’s minimalist (and gorgeous) bell-chords on the piano. Hall comes in for a final ride, the entire rhythm section getting simpler and quieter until the second half of the final chorus where it disappears completely. Hall’s unaccompanied clarinet finishes the selection, only joined by one held note from the rhythm after his final note.

Hal, I hope I didn’t wax too rhapsodic about this one track, but there is so much going on, even as so little is being played. First, what a perfect group Bob Greene was able to assemble. Second, the musicians serve the music, rather than making it their servant. This one touched me so deeply it’ll be the one by which I judge other versions.

How can you follow that?

HS: Let’s detour away from Morton’s music for just a moment… On the LP of duets between Bob Greene and Don Ewell, there is a Greene original entitled “Mister Jess.” (The liner notes mention that Greene was a fan of Jess Stacy’s music as well as Morton’s)! And on the Economy Hall Breakdown album, “Stompin’ For Sonny” recalls Stacy’s playing on the “Impromptu Ensemble” blues that closed out many of the Eddie Condon Town Hall concerts. Fast-forward to 2008 and a lovely recording session with Greene, clarinetist Bobby Gordon, and guitarist Howard Alden…There are Morton phrases on “I Ain’t Got Nobody,” but you can’t miss those Stacy-like tremolos!

JB: As much as I admire Greene’s chops on the upbeat numbers, it’s the slow selections where I hear how soulful his playing really is, Hal. Here, Bob Greene is joined by one of our favorite clarinetists, the magnificent—and much missed—Bobby Gordon. The side starts with a held chord from Greene (the top note being the first note of the melody) that suspends time until he eases into the feel, sprinkling reflective, almost mournful Jellyisms throughout until Gordon’s entrance at the bridge. A delightful exchange occurs at the very end of the first chorus when Greene executes a trademark Morton figure that Gordon repeats going into his solo chorus. Such a great connection! Greene’s piano solo is a graduate course in referencing not just Jelly Roll and all early New Orleans style piano, but also, as you point out, some terrific “Stacyisms” such as the right-hand octave passages with tremolos in the inner voices and dramatic dynamics going back and forth between caressing and carousing! He backs way down as he finishes his solo and Gordon re-enters. Greene takes front seat during the final bridge with more “Jessy Roll” and the two masters gently put the tune to bed. Deep and moving.

HS: That’s a great description of the whole performance. Let’s hear another track that is “sweet, soft” with “plenty rhythm, plenty swing” as Mr. Morton would say: “Mamie’s Blues,” recorded while Bob Greene was in Japan as a guest of the New Orleans Rascals.

JB: Alright, buddy! This brings up galaxies of discussion! First, again Greene outdoes even Morton when it comes to pathos and beauty. It’s remarkable how the spaces between the notes have as much meaning as (or maybe more than) the notes played. As well, this video confirms what I thought I heard on the previous two numbers…Greene is a “hummer” (in good company with the likes of Ralph Sutton, Erroll Garner, and CT-based New Orleans pianist Bill Sinclair, among others)! He’s always humming in tune, though…a haunting “chanted” vocal accompaniment to his playing. Moreover, this moving arrangement was featured in the 1978 film Pretty Baby, pretty much note-for-note.

My Mom gifted me the soundtrack LP the year the movie came out, so I was 11 when I first heard the music of Bob Greene. As a kid, I couldn’t wrap my head around the band and orchestra selections—I was already in tune with the crisp attack and intonation of the West Coast Revival bands as well as the sound my local band, the Galvanized Jazz Band, so the New Orleans “Revival” sound of the band sides—used to represent the sounds of 1917 New Orleans, which opens a whole can of musical worms—didn’t resonate at the time. But the PIANO sides resonated with my prepubescent ears in a profound way. I do hope someone more tech savvy than I (skip the eleven-year-olds, find me a kid who’s just turned three) will put the soundtrack online for listening. Greene performs seven selections, including one with a vocal by James Booker (!), and also is featured on “Big Lip Blues,” playing with two legendary New Orleanian musicians, clarinetist Louis Cottrell and bassist Walter Payton.

My Mom gifted me the soundtrack LP the year the movie came out, so I was 11 when I first heard the music of Bob Greene. As a kid, I couldn’t wrap my head around the band and orchestra selections—I was already in tune with the crisp attack and intonation of the West Coast Revival bands as well as the sound my local band, the Galvanized Jazz Band, so the New Orleans “Revival” sound of the band sides—used to represent the sounds of 1917 New Orleans, which opens a whole can of musical worms—didn’t resonate at the time. But the PIANO sides resonated with my prepubescent ears in a profound way. I do hope someone more tech savvy than I (skip the eleven-year-olds, find me a kid who’s just turned three) will put the soundtrack online for listening. Greene performs seven selections, including one with a vocal by James Booker (!), and also is featured on “Big Lip Blues,” playing with two legendary New Orleanian musicians, clarinetist Louis Cottrell and bassist Walter Payton.

HS: I also hope that the folks who read this article will be inspired to search for Bob Greene’s recordings listed in the discography. Anyone who wants the material that is not currently available on CD or online may be able to find the records on eBay, Discogs.com and/or CDandLP.com.

Bob Greene passed away on Oct. 13, 2013. In honor of his preservation of Morton’s music, let’s close this article with one of the tracks from the 1974 World of Jelly Roll Morton LP that is available on YouTube: “Mr. Jelly Lord.”

JB: One of the nice things about this track is we get to hear Bob Greene’s voice as he recites a typically self-aggrandizing poem of Jelly’s to set up the ensuing tune. He then plays a solo introduction and essaying of the first strain, actually improvising in pure Jelly style rather than copying the original recording! The rhythmic set-up for cornetist Ernie Carson’s dramatic entrance is perfect, and again, Carson improvises on the section rather than referencing the original. The band enters one by one in this order: drums (Tommy Benford); bass (Milt Hinton); clarinet (Herb Hall), trombone (Eph Resnick)—guitarist Alan Cary receives no special entrance; it’s hard to hear him so he might have come in at the same time as Benford? Anyhow, Hinton, Hall and Resnick all solo, leading to a joyous ride by Greene! He pours it on with relish, using every characteristic Morton phrase and convention he can fit in, and it’s glorious! The band stormily returns—this last ensemble highlighted by a double-time two-bar break for Greene—and wails out, with one more surprise two-bar piano break as a coda heralding the triumphant final chord!

Hal, from its placement on the record, this looks like the start of the live concert, and what a beginning it is! From this track I glean two telling things about Greene. First, as quiet as his demeanor appeared, he was also a showman with a sense for the dramatic. Building the band one person at a time at the start of a concert or set is something I’ve enjoyed doing (most notably with my Waller Legacy band) and it ALWAYS works! Second, Bob Greene was neither transcriber or copyist. He utilized the “sound” of Jelly Roll in his and the band’s playing, without ever re-creating. The title The WORLD of Jelly Roll Morton aptly describes the intent: create an aura with the music at the center. Greene’s band was so refreshing that John S. Wilson, then-music critic for the New York Times enthused (with my italics): “[the band] projected the flavor of Mr. Morton’s music—the breaks, the slurs, the accents, the coloring that are such memorable elements in the whole Morton repertory.” No faint praise, that, and well-deserved!

HS: I chose the subject for this month’s column, Jeff. What do you have in mind for next month’s topic?

JB: Since he appeared once this month, let’s take a closer look at cornetist Johnny Wiggs! In the meantime, thanks for supplying the following discography for those who would like to hear more Bob Greene.

A BOB GREENE DISCOGRAPHY

(12” vinyl LPs unless otherwise noted)

Conrad Janis and his Tailgate Jazz Band (1950) GHB BCD-71

Sidney DeParis and his Blue Note Stompers (1951) Blue Note 7016 10” LP; Blue Note B-6501

Carl Halen and the Washboard Five (1951) Knickerbocker 3, 4 78 RPM; Riverside RLP 2502 10” LP

Shel Silverstein with the Red Onion Jazz Band Hairy Jazz (1959) Water CD-214

St. Peter Street Strutters (1964) Delmark DE-234 CD

Jim Robinson Economy Hall Breakdown (1965) Delmark DE-235 CD

Zutty and the Clarinet Kings vol. 1 (1967) Fat Cat’s Jazz FCJ – 100

Zutty and the Clarinet Kings vol. 2 (1967) Fat Cat’s Jazz FCJ – 101

Bob Greene’s International New Orleans Jazz Band (1968) Fat Cat’s Jazz FCJ-108 (1968)

Don Ewell – Bob Greene Duet (1969) Fat Cat’s Jazz FCJ-110

Carson-Greene St. Peter Street Strutters vol. 1 (1970) GHB-56

Carson-Greene St. Peter Street Strutters vol. 2 (1970) GHB – 57

Zutty Singleton – Johnny Wiggs Jazz For The Seventies Fat Cat’s Jazz FCJ-116 (1970)

Ricardo’s Jazzmen Featuring Bob Greene (1970) 1 track only CSA Records CLPS-1002

A Tribute to Jelly Roll Morton (1972) Storyville SLP-221

Bob Greene & the Peruna Jazzmen Jelly Roll Morton Revisited (1972) Fat Cat’s Jazz FCD-139

Bob Greene’s World Of Jelly Roll Morton (1974) RCA Red Seal ARL 1-0504

Leon Redbone Double Time (1977) 1 track only Warner Brothers BS-2971

Music From the Soundtrack of Pretty Baby (1978) ABC Records AA-1076

Eiji Kitamura Meets Bob Greene Polydor 28MJ 3107 (1981)

Bob Greene’s Jelly Roll Morton Jazz Band (1998) GHB BCD-145

The New Orleans Society Orchestra Live in Amagansett (2007) PopFree Records (Streaming)

Bob Greene, Bobby Gordon, Howard Alden All That I Ask Is Love (2008) GHB BCD-517

New Orleans Rascals 50th Anniversary Concert (2011) New Orleans Rascals CD-50

Hal Smith is an Arkansas-based drummer and writer. He leads the El Dorado Jazz Band and the

Mortonia Seven and works with a variety of jazz and swing bands. Visit him online at

halsmithmusic.com

Jeff Barnhart is an internationally renowned pianist, vocalist, arranger, bandleader, recording artist, ASCAP composer, educator and entertainer. Visit him online atwww.jeffbarnhart.com. Email: Mysticrag@aol.com