My grandmother used to say she couldn’t see because she had Cadillacs in front of her eyes. Well, it must be genetic because I’ve gone from Volkswagen Bugs to Ford Transit Vans blocking my vision. However, I recently received good news. I am eligible for cataract surgery in June that should clear my visual parking lot.

Meanwhile, I’m blowing off the dust this month on a remarkable archive collection Dr. Gary Tash and his wife Sharon have shared with me. With writing assistance I’m anxious to describe what they have.

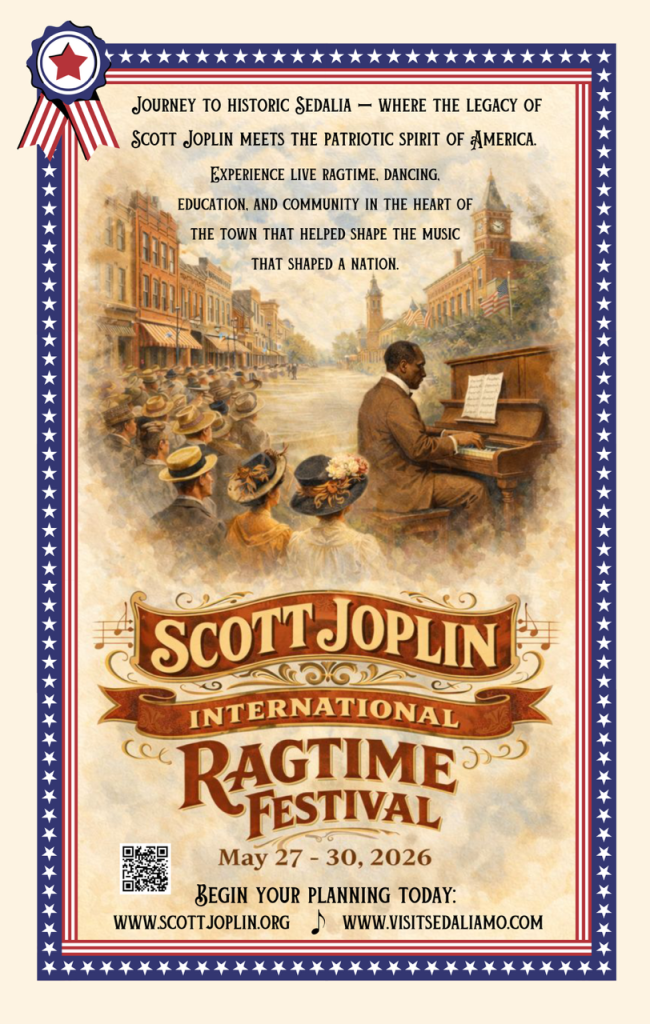

This remarkable couple actively support their local ragtime community. Sharon was a St. Louis accompanist and piano teacher for over 50 years. Gary, a retired physician, discovered ragtime thanks to Max Morath concerts and recordings.

He contacted me a few years ago about Max and has stayed in contact. In a recent telephone conversation, he happened to mention a collection of documents he had acquired some time ago, and wondered if I would be interested in what he had.

It turns out the documents comprised the research papers a graduate student had accumulated on St. Louis opera and cabaret star Helen Traubel. The Tashes had carefully stored the archive all these years wondering about its significance. The graduate student died before writing the paper and his work was destined for a dumpster when Gary and Sharon salvaged it.

It has been fascinating to go throu

You've read three articles this month! That makes you one of a rare breed, the true jazz fan!

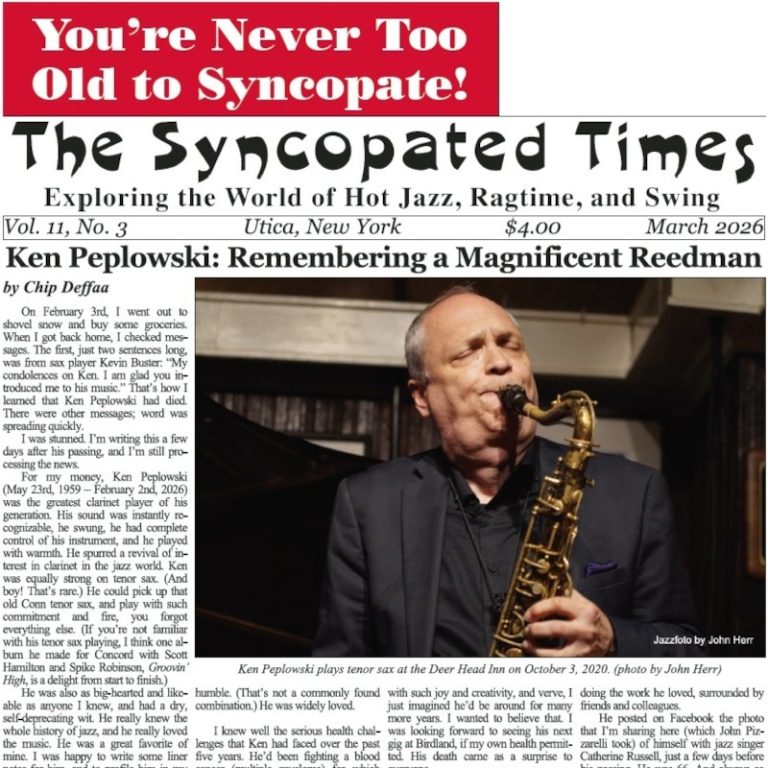

The Syncopated Times is a monthly publication covering traditional jazz, ragtime and swing. We have the best historic content anywhere, and are the only American publication covering artists and bands currently playing Hot Jazz, Vintage Swing, or Ragtime. Our writers are legends themselves, paid to bring you the best coverage possible. Advertising will never be enough to keep these stories coming, we need your SUBSCRIPTION. Get unlimited access for $30 a year or $50 for two.

Not ready to pay for jazz yet? Register a Free Account for two weeks of unlimited access without nags or pop ups.

Already Registered? Log In

If you shouldn't be seeing this because you already logged in try refreshing the page.