In the latter 19th century, a few daring publishers decided to try and combine their hustling status with the phonograph. In the 1890s it was still a very far fetched idea to combine these two aspects. In 1897 Russell Hunting and a few other prominent recording artists teamed up to make records under the permission of major publisher Joseph Stern. They called this company the Universal Phonograph Company. Unfortunately this revolutionary combination only lasted just about a year, but you can still see many of their advertisements on the inside of Stern sheet music. By the middle 1900s, the idea of combining recording and publishing was much more viable. By then many publishers of Tin Pan Alley saw the phonograph as more than just a novelty. Perhaps the most successful of these early endeavors was that of bandleader Fred Hager and songwriter J. Fred Helf, that ended up becoming one of the most successful publishing houses of the decade.

J. Fred Helf had been associated with recording folks since before 1900, as a few of his first New York popular pieces were published by recording folks. In 1899 Helf’s first major hit “How’d You Like to Be the Iceman?” was published by W. B. Gray, who had his office right next door to the Columbia recording lab on 27th street. Later within that year he also got two more pieces published by Columbia studio pianist Fred Hylands. While Helf was himself a skilled performer, he never made any records (as far as we know), but he associated with many phonograph folks from the beginning of his career. Consequently, many of his pieces became popular with recording artists of all labels. Not long after he became one of the most well connected and prized songwriters of the era.

All the most famous publishers wanted to use him exclusively, and all failed to do so except for Sol Bloom. Bloom was known as a popular Chicago based publisher, but as his business grew exponentially, he was forced to make the move to New York. A little over a year after Bloom hired Helf, Fred Hager came in with a new “Indian” piece he had written. This was to be called “Laughing Water” and would soon become one of the best selling sheets of the decade. From this piece, it seemed that nearly overnight Hager went from a nobody local bandleader to a national success earning thousands in royalties. This unprecedented success inspired Hager to pitch a new publishing venture, and after a little while of considering, Helf eventually agreed. Like any new publishing business, it took some time to get off the ground, but thankfully they were both well connected and had a decent amount of money to start with.

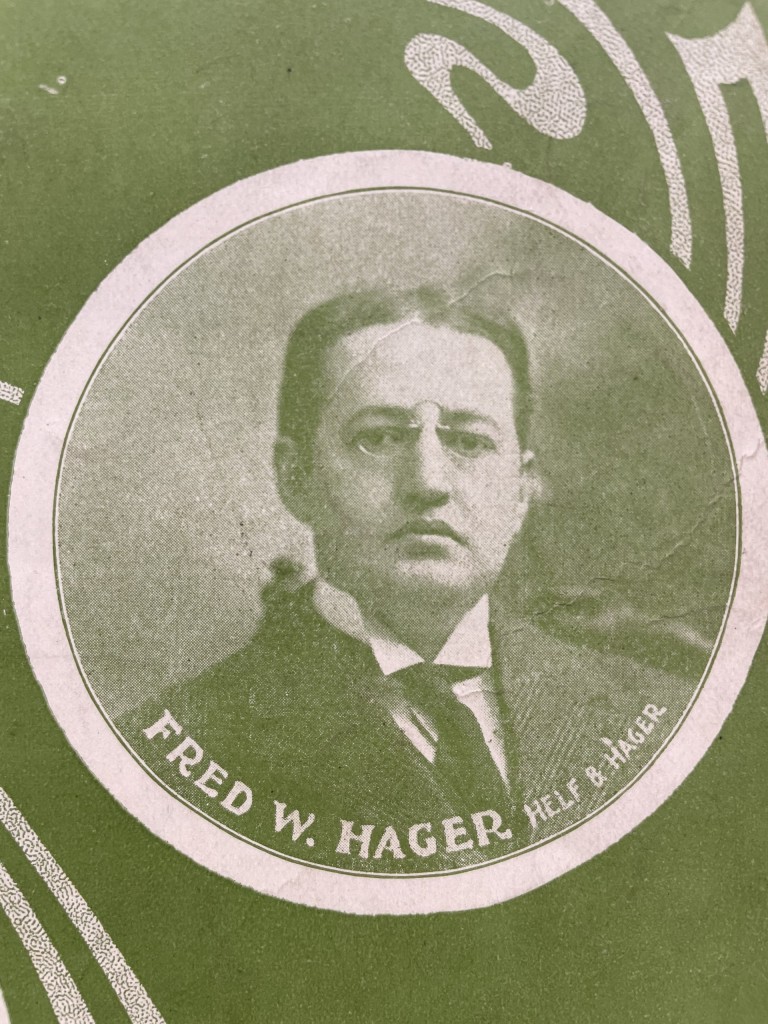

(author’s collection)

At the time Helf and Hager joined forces, in December of 1904, Hager had just begun cutting ties with Zon-O-phone. He had been one of the most important workers for the company since its inception in 1900, but after Victor fully bought the company earlier that year, he had begun to rethink his association with them. It seemed that after Victor took over, Hager had less freedom in the studio. It didn’t help that the management treated Zon-O-Phone as second class records.

He had seen a few other recording artists become relatively successful in publishing, and thought it a good idea for him to try it himself.

Joining with Helf turned out to be one of the most profitable decisions both of them had ever made. They started small at 55 West 28th Street, right in the middle of the now landmarked Tin Pan Alley, but it didn’t take long for them to get recognized by the wider publishing world. The first major success they published was “Everybody Works but Father.” It is very likely that one of them came to the famous minstrel performer Lew Dockstader and pitched the song to him directly. From the moment it was published, it was synonymous with Dockstader. They had actually published two other songs before this that were also handed to Dockstader, one of them being “There’s a Dark Man Coming with a Bundle.”

Dockstader was one of the most popular performers in the US at the time, and he also ran his own major franchise of minstrel shows. Many recording artists performed under his name, a certain Denver native, Billy Murray, began his career this way. In keeping with the minstrel show theme, one of the first things Helf and Hager published was a piece by Ernest Hogan, a somewhat bold move by a new white publisher. Hager was also able to get nearly every new song they published recorded by any of the major labels at the time, even if he had just formally left the recording business, albeit temporarily.

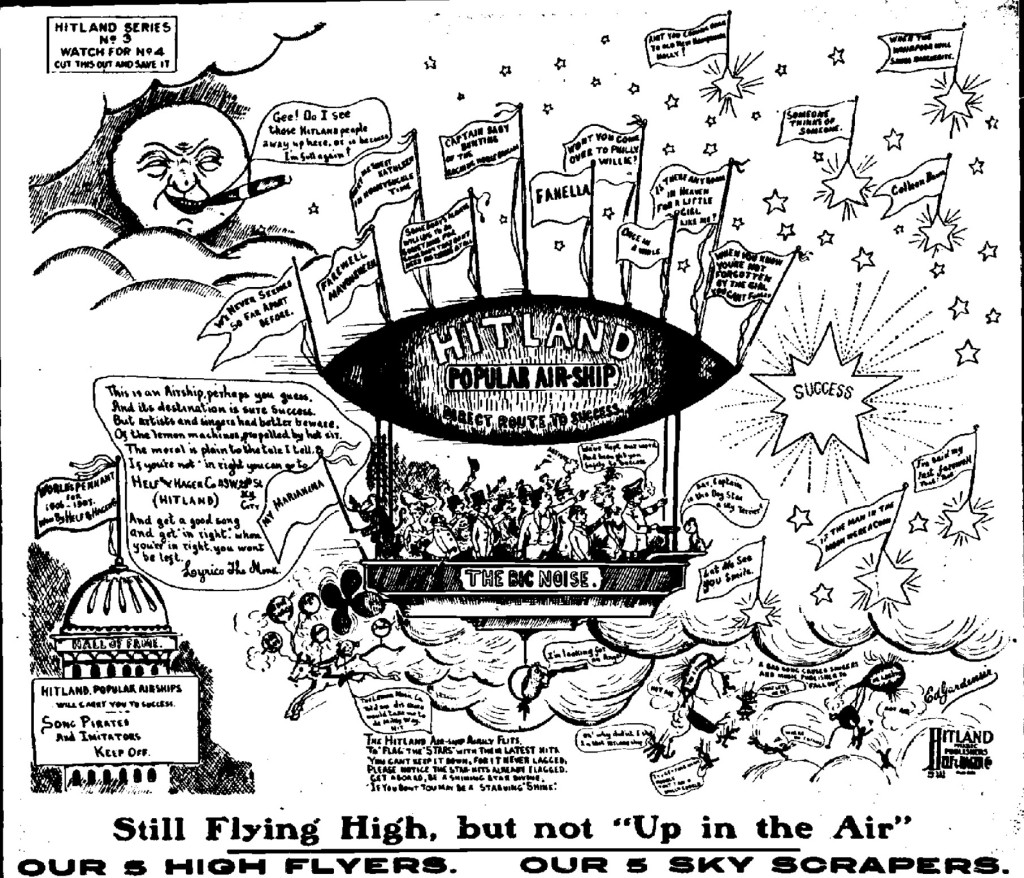

What might come as a surprise is that Hager was incredibly effective at creating eye-catching advertisements. From the middle of 1905, Helf and Hager created some of the most interesting but strange full page advertisements. These ads often graced the back pages of The New York Clipper. By 1906 their advertisements had become more elaborate. One thing that distinguished theirs from other publishers are the illustrations. These illustrations were crudely drawn and incredibly elaborate, penned by one of their own writers, Ed Gardenier. There were scenes of folks fishing for song successes, hunting for them, and finding an oil well gushing with them.

As one could have guessed, a good percentage of their entire output was composed by Helf. For some reason, after he joined with Hager, Helf wrote more songs than he ever had. In this situation, part of this sudden burst in productivity could have been motivated by money, as most of these songs were relatively similar to one another. It’s also interesting to note that during this period, this was the first time in either of their careers that both Helf and Hager had any sort of free time. Helf had been constantly employed as a writer for various different publishers since 1899, and Hager had been one of the only competent workers for Zon-O-Phone since about the same time. Consequently, between 1905 and 1909 Hager became obsessed with collecting magazine and newspaper clippings about himself and his close friends. The scrapbook pages of his that survive today were compiled during his time working with Helf.

While their success only increased, Helf became even more popular to interview. In June of 1905, He was featured on the cover of Billboard, and in many subsequent issues had his own column about what songs were going to become hits this season. To a few accounts, he was one of the most amiable men to chat with in the music world, and one of the most knowledgeable. One publication that they weren’t too successful about getting into was The Music Trade Review. Throughout a majority of their time in operation, this publication was ruled by others like Harry Von Tilzer and Joseph Stern. Oftentimes in that publication, however, the phonograph section often noted the doings with Hager in the new business.

While the success seemed endless, it wasn’t permanent. Even if, for a short period between 1907 and 1908, Helf and Hager was one of the most successful sheet music publisher in the country, they did eventually go bankrupt in 1910. How exactly this occurred is anyone’s guess, as by the time they had officially declared it, they had just moved to an even more prestigious office at 1412 Broadway, not even two blocks from Times Square.

However, in early 1910, there was a fire that broke out on that block of Broadway that destroyed much of their office. Other surrounding theaters were threatened by this fire, but unfortunately Helf and Hager suffered the most, burning much of their stock. It is because of this fire that today some of their sheets are much more common than others. Some of them show up one after another, while others remain incredibly scarce today.

Helf was glad to pick himself up and get back into the business, even after grimly going through the ash, but Hager was devastated. Hager did not want to return to publishing after this, and he never did. It seemed like a quick five years, but it ultimately would earn Helf and Hager royalties for the rest of their lives, and after Helf died in 1915, Hager would receive Helf’s royalties, making him an even richer man. Even by 1950 Hager was still receiving royalties from some of Helf’s songs.

R. S. Baker has appeared at several Ragtime festivals as a pianist and lecturer. Her particular interest lies in the brown wax cylinder era of the recording industry, and in the study of the earliest studio pianists, such as Fred Hylands, Frank P. Banta, and Frederick W. Hager.