We first met, Jazz and I, at a dance hall dive on the Barbary Coast. It screeched and bellowed at me from a trick platform in the middle of a smoke-hazed, beer-fumed room.” — Paul Whiteman, 1915

I’ve lately been teaching livestream extension courses about early Jazz and Swing for local universities. I recently surveyed San Francisco Jazz from 1916 to ’66 reflecting its boomtown origins and distinctive culture. Here’s what I learned about a time spanning from the wild Barbary Coast era to when most of the Dixieland bars closed on the eve of The Summer of Love.

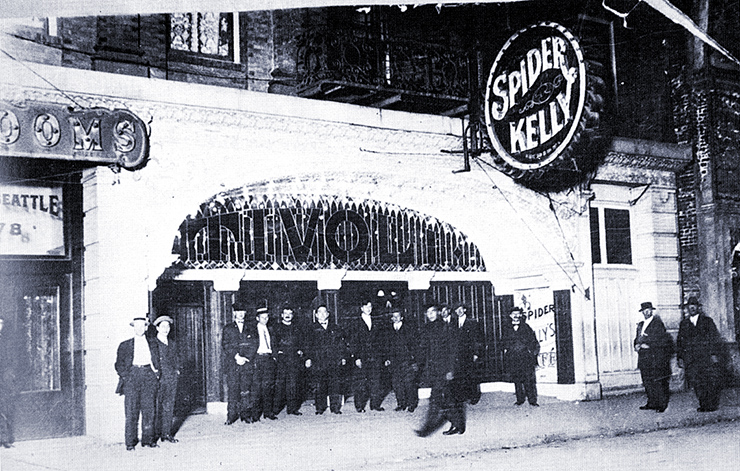

The Barbary Coast World-famous Vice District

Dating back to the California Goldrush of 1849, the Northeastern quarter of San Francisco near the waterfront was a well-established vice district. Prostitution was the main attraction followed by gambling, drinking, drugs and rough trade of all kinds.

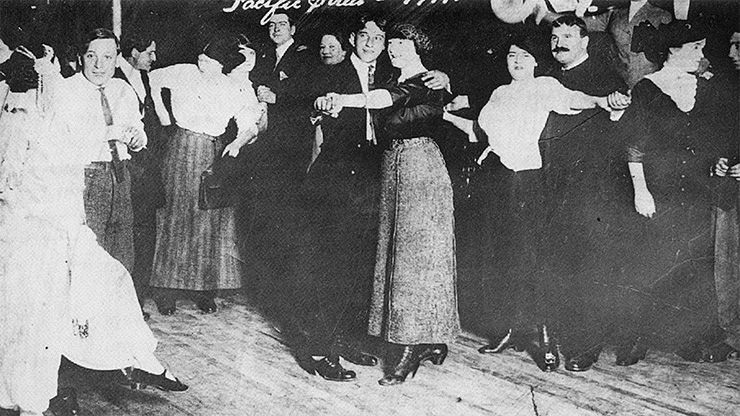

Kidnapping of sailors was so commonplace that the term “Shanghaiing” probably originated there. The dance halls were a major attraction and point of origin for several dance crazes: The Turkey Trot, The Grizzly Bear and most famous of all, the Texas Tommy.

Also known as “Terrific Street,” homosexual prostitution, drag performance and freak shows were openly present. In 1876, literary observer B.E. Lloyd encountered:

“Dance houses and concert saloons, where blear-eyed men and faded women drink vile liquor, smoke offensive tobacco engage in vulgar conduct, sing obscene songs. . . Low gambling houses thronged with riot-loving rowdies in all stages of intoxication are there.”

“Opium dens where heathen Chinese and God-forsaken women and men are sprawled in miscellaneous confusion . . . Licentiousness, debauchery, pollution, loathsome disease, insanity from dissipation, misery, poverty, wealth, profanity, blasphemy and death are all here.”

What follows is a vivid description excerpted and paraphrased from a 1932 University of Chicago white paper. One Paul G. Cressey, a former Special Investigator for the Juvenile Protective Association, offers a striking depiction:

“In the Barbary Coast halls everybody — fishermen, scavengers, dishwashers, cooks, waiters, seamen—came in working clothes, just ‘washed up’ some. Everybody ate, smoked, chewed gum while they danced with their hats on. Spanish men in cowboy suits and sombreros, red kerchief and sash, were among the crowd.”

“The girls were Portuguese, Italians, French and Americans. The orchestras . . . usually consisted of an accordion, horn, drum, and piano. There was no special police officer, as he was always beaten up when an attempt was made to employ one. In 1913, the Police Commissioner prohibited dancing in any cafe, restaurant, or saloon where liquor was sold. This wiped out dancing and resulted in the appearance of the so-called “closed” hall in the adjoining districts.”

“There the girls were employed to dance with patrons on a commission basis and salary. The shortened dance number and the ticket-a-dance system, by which the girl received her pay on the basis of the number of tickets she could collect, ‘legitimized’ their establishments camouflaging them as dancing schools.”

To encourage drinking, “clip-joints” employed so-called “b-girls” (Bargirls). They mingled amongst customers dressed either in skimpy attire or disguised as civilians in street clothes. Drinking decoy beers or watered-down cocktails purchased for them by customers, they received commissions on alcohol sales.

The Barbary Coast was comparable in many ways to the lawless Beale Street section of Memphis or the red-light Storyville district of New Orleans before 1917. Tom Stoddard was the first to document the music in his landmark work, Jazz on the Barbary Coast (Heyday Books, 1982, 1998). Between 1913-21 the section was gradually closed by a series of rolling crackdowns urged by the Hearst newspapers and raids organized by the Police Commissioner.

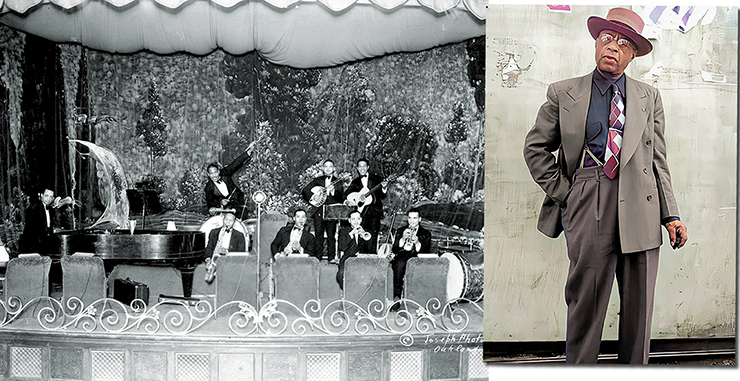

Sid LeProtti’s So Different Jazz Band, 1910-30

Sid LeProtti ran orchestras on Terrific Street and in San Francisco for more than two decades becoming dean of the Barbary era bandleaders. Merely piano and drums at first, his outfit expanded to four pieces with a string bass and clarinet, then adding flute or piccolo. A 1915 photo shows his lineup of saxophone, clarinet, flute, piano, drums and a string bass, the latter probably bowed not plucked. His 1923 band, seen in the accompanying photo had ten instruments plus a singer — Lottie Brown seen posed with a clarinet.

The bandleader progressed through a series of musical styles, landing on a form he called “Ragtime.” Which probably signifies a raggy Jazz-like improvised music played for dancing, similar to what was heard at the time on Beale Street or in Storyville. In 1912 he “switched to the New Orleans-type music . . . you take a chorus, I’ll take a chorus. . . Dixieland-style.”

In interviews, LeProtti says that at Purcell’s So Different Saloon they played short versions of dance tunes — up to 25 or 30 per hour. Brass dance-tokens cost twenty-cents each, split between dancers and the hall, or sometimes with the band.

Incidentally, LeProtti was most likely the original composer of “Canadian Capers.” One of his main themes in that popular rag was appropriated by publishers Henry Cohen and Chandler White in their edition.

Jelly Roll Morton & King Oliver Come to Visit

California, Frisco, and Terrific Street were popular destinations for many of the great New Orleans musicians early in their travels. Trumpeters Freddie Keppard, Papa Mutt Carey and Joe King Oliver, clarinetist Wade Whaley, trombone player Kid Ory and Jelly Roll Morton all performed in or near Frisco before winning wider fame elsewhere.

In 1918-19, Jelly Roll Morton arrived and for a short time ran a bar called The Jupiter. LeProtti corroborates his braggadocios and pugnacious demeanor. Jelly welcomed himself to town by declaring that he would steal the bandleader’s musicians and popularity.

By the time Joe “King” Oliver visited in 1921, he was already a monumental figure having been monarch of the New Orleans horn players. Two years later, his Creole Jazz Band would make the first widely heard authentic African American Jazz records.

It seems that his visit aroused the local bandleader’s jealousy. At first and LeProtti wasn’t impressed, until Joe sat-in with his So Different Jazz Band. When he decided that, well maybe this Oliver fellow was okay after all. When response to the band was tepid at the Pergola Dancing Pavilion on Market Street, the Creole Jazz Band worked at the Entertainers Club in Oakland and various miscellaneous jobs.

New Orleans-born Clarinetist Clem Raymond

Clem Raymond was born in New Orleans c. 1895. The son of a Methodist minister, he was trained on clarinet by master musicians Lorenzo Tio, Jr. and Jim Humphrey, leaving town a skilled musician. His first job on the Barbary Coast in 1915 was in the band of Alma Eightower, a New Orleans-born multi-instrumentalist who played piano, clarinet, drums and more.

He also worked for a couple years with Jelly Roll Morton, mostly in Los Angeles in a band Jelly called the Incomparables. Clem says that in those days Morton played his own compositions exclusively, “not condescending to play popular tunes.”

Clem Raymond moved to Oakland permanently in 1922 launching his own band sometime before 1930. He succeeded by specializing in performing throughout the greater Northern California region, taking jobs as far distant as Sacramento or Ft. Bragg on the coast, some 150 miles North. Raymond worked intermittently into the mid-1950s, recording with clarinetist George Lewis and bandleader Dick Oxtot in San Francisco — first issued in the 1990s.

The Raymond band performed at a longstanding popular attraction on Market Street that Duke Turner recalled for Tom Stoddard: “In 1931, I played the Walkathon. . . at Ripper Dan’s. . . where they get out and dance or walk until they fell. The last one standing wins a prize.”

Drummer Charlie “Duke” Turner was a Berkeley native. After playing with high school “kid bands” he joined Clarence Banks jazz band in 1922-23. Then he worked “with Clem Raymond’s band a lot” and Wade Whaley, launching his own eight-piece Duke Turner’s Musical Cavaliers at Persian Gardens in Oakland in 1931.

Turner recalls working in Frisco at a “colored walkathon” down on Mission Street in the band of Elmer Fain:

“. . . we had a women piano player called Princess Bell. Another gal we had around was Helen Fletcher, who played trombone, and she was as good as anybody around. . . She played with lots of bands. She’d put her hair up and wear men’s clothes and most people didn’t notice the difference.”

Good Times in Oakland

Across the Bay in Oakland there were abundant thriving dance and music venues: the upscale Entertainer’s Club where King Oliver performed, the Toyon Inn, Kentucky Stables and very popular New Republic of China Restaurant on Broadway. At Lakeside Gardens the seven-piece Clarence Banks Syncopators Jazz Band held forth during 1922-23.

Sweets Ballroom opened downtown in the early 1920s and is still operating. Clem Raymond ran a band at Webb’s Hall on Eighth Street. Duke Turner recalls Webb’s was “a big barn of a place and they used it for a roller-skating rink, too. Sometimes they had skating and dancing at the same time.”

Sid LeProtti moved to Berkeley in the 1920s, running dance bands and opening a cigar store. Around 1930 he migrated further East to the suburb of Walnut Creek, where he continued running orchestras and his tobacco shop on Main Street was a local fixture for 25 years.

Last of the Barbary Coast

Open prostitution and vice in the Barbary Coast environs were gradually suppressed. After a hiatus, many of the formerly notorious clubs reopened in the late 1920s, though more strictly regulated.

Purcell’s So Different Club restarted as did Red Kelly’s across the street. The largest of the grand dance halls resumed, The Hippodrome featuring an eighteen-piece orchestra. After further sanitizing, the area was refashioned as the International Settlement in 1933 appealing primarily to out-of-towners and tourists.

The Barbary Coast lived-on in legend and popular culture, dramatized in songs, movies, dime novels and theater. The 1936 motion picture “San Francisco” starred Clark Gable as “King of the Barbary Coast and a television series in the 1970s starred actor William Shatner.

However, excepting LeProtti’s incidental piano music taped in the 1950s, I find no surviving recordings directly associated with this earliest era of San Francisco jazz. Nevertheless, links at the end of this article lead to illuminating clips and documentaries vividly evoking the era.

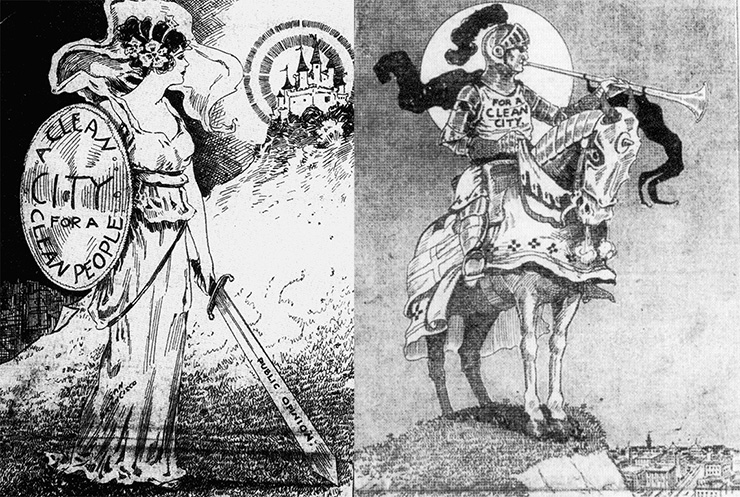

Jazz, Earthquakes, Crime & Reform

In a recent book, Dangerous Rhythms: Jazz and the Underworld, author T. J. English makes a convincing case that criminal syndicates were deeply enmeshed in the early development of Jazz music, venues and enterprises.

During Prohibition (1920-33) the nation’s top nightclubs — like the Sunset Cafe in Chicago or the Cotton Club in Harlem — were incubators and crucibles for the new music. Such clubs were owned by gangsters and capitalized by bootleg liquor. Well into the 1960s, the highest profile and most successful nightclubs in most big cities were owned or operated by mobsters.

The author stresses that the underworld economy functioned through the acquiescence of corrupt cops, big-city political machines and local powers-that-be. This nexus was epitomized in the wild jazz scene that flourished in and around Kansas City under the criminal political regime of Tom Pendergast.

By contrast, a different course was dictated in San Francisco by the Great 1906 Earthquake and Fire. During reconstruction, political reformers and powerful city fathers took charge of rebuilding a “clean city” aiming to shape a shining beacon of the West which was subsequently displayed in the dazzling 1915 Panama Pacific International Exposition and forward-leaning Treasure Island World’s Fair of 1939.

Prohibition further curtailed Frisco nightlife. Combined with the suppression of vice and a growing economic depression, many entertainers headed for Los Angeles. In San Francisco, hegemony was granted to respectable hotel orchestras and tepid society dance bands into the 1940s. Three accomplished local bandleaders rose to foremost prominence: Anson Weeks, Ernie Hecksher and Del Courtney.

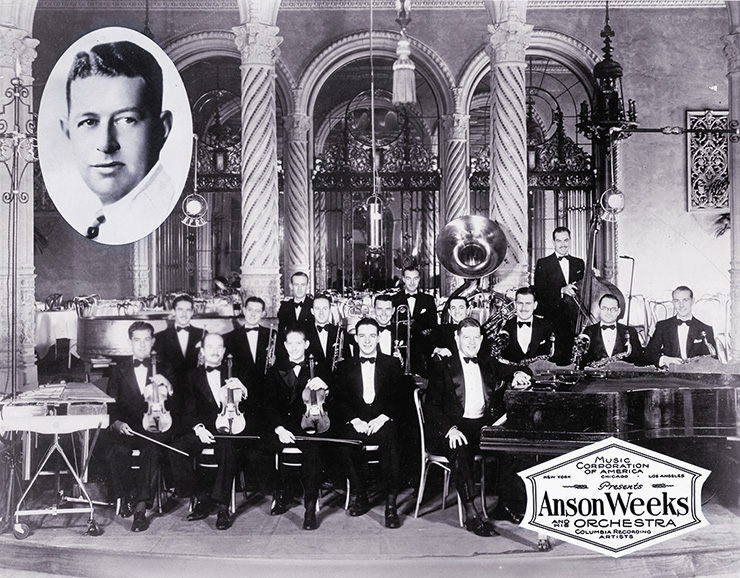

King of the Nob Hill Dance Bands: Anson Weeks

Born in Oakland in 1896, pianist Anson Weeks recorded prolifically under the moniker “Hotel Mark Hopkins Orchestra.” From 1929 to 1932 he broadcast coast-to-coast nightly from the hotel ballroom on the “Lucky Strike Magic Carpet.” During the early 1930s Weeks was associated with singers Bing Crosby and Bob Crosby, backing Crosby-the-younger in his earliest films.

Born in Oakland in 1896, pianist Anson Weeks recorded prolifically under the moniker “Hotel Mark Hopkins Orchestra.” From 1929 to 1932 he broadcast coast-to-coast nightly from the hotel ballroom on the “Lucky Strike Magic Carpet.” During the early 1930s Weeks was associated with singers Bing Crosby and Bob Crosby, backing Crosby-the-younger in his earliest films.

But in 1940, a serious automobile accident sidelined Weeks for more than a decade. He resumed a high-profile residency at the Palace Hotel in 1956. After retiring he fronted dance bands in Sacramento before passing in 1969.

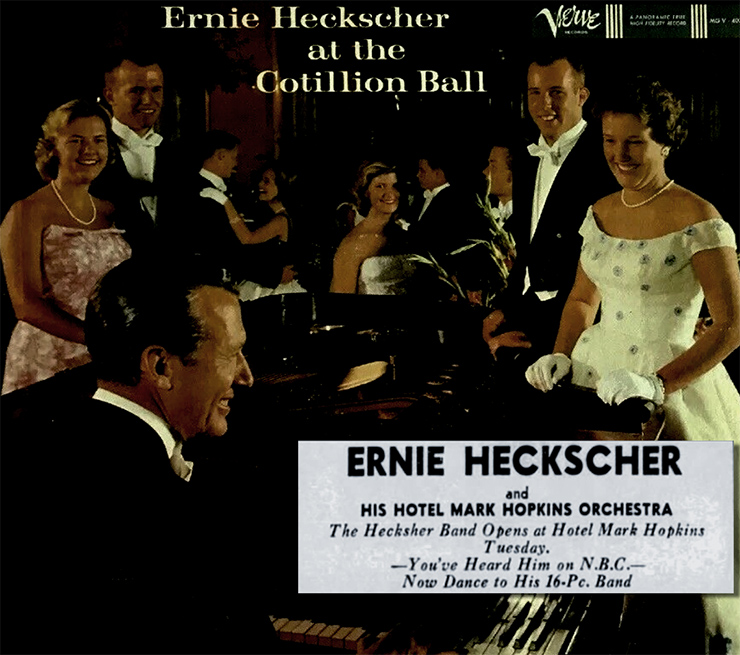

Thirty-six Years atop Nob Hill: Ernie Hecksher

Though Ernie Hecksher was born in London, the pianist was raised in San Francisco from a tender age. His studies at Stanford University were secondary to the social connections he garnered playing for swell cotillion balls and posh social dances.

Though Ernie Hecksher was born in London, the pianist was raised in San Francisco from a tender age. His studies at Stanford University were secondary to the social connections he garnered playing for swell cotillion balls and posh social dances.

Beginning in 1939, his dance orchestras performed at the most prestigious hotels: The Palace, The Clift, the Mark Hopkins and Fairmont hotels. The bandleader’s success was facilitated by a remarkable musical partner, his wife.

Sallie Hecksher (nee Cooley) was a skilled arranger and composer. Also an artistic polymath, her clothing and hat designs were sold at high-end department stores like I. Magnin and Abercrombie & Fitch. She was also an accomplished Asian-style sumi painter with more than 15 gallery shows to her credit.

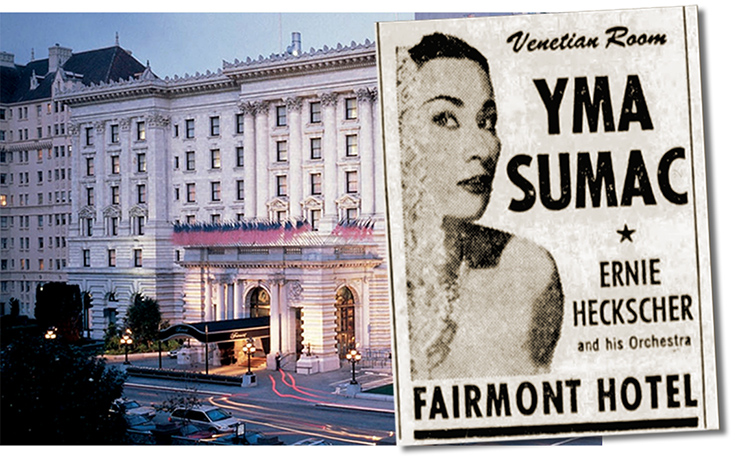

Ben Swig was a powerful real estate magnate on both coasts and the influential owner of the Fairmont Hotel. In 1948 he hired Hecksher to lead the house orchestra in the plush Venetian Room. It was an opulent performance space mimicking a Venetian palace where in 1961 Tony Bennett premiered “I Left my Heart in San Francisco.”

Hecksher backed many famous singers at the Venetian Room: Ella Fitzgerald, Peggy Lee, Harry Belafonte, Marlena Dietrich, Nat King Cole, Sammy Davis, Jr, Lena Horne, Edith Piaf, Bobby Short, Tina Turner and James Brown. He issued some 15 record albums before retiring in 1984.

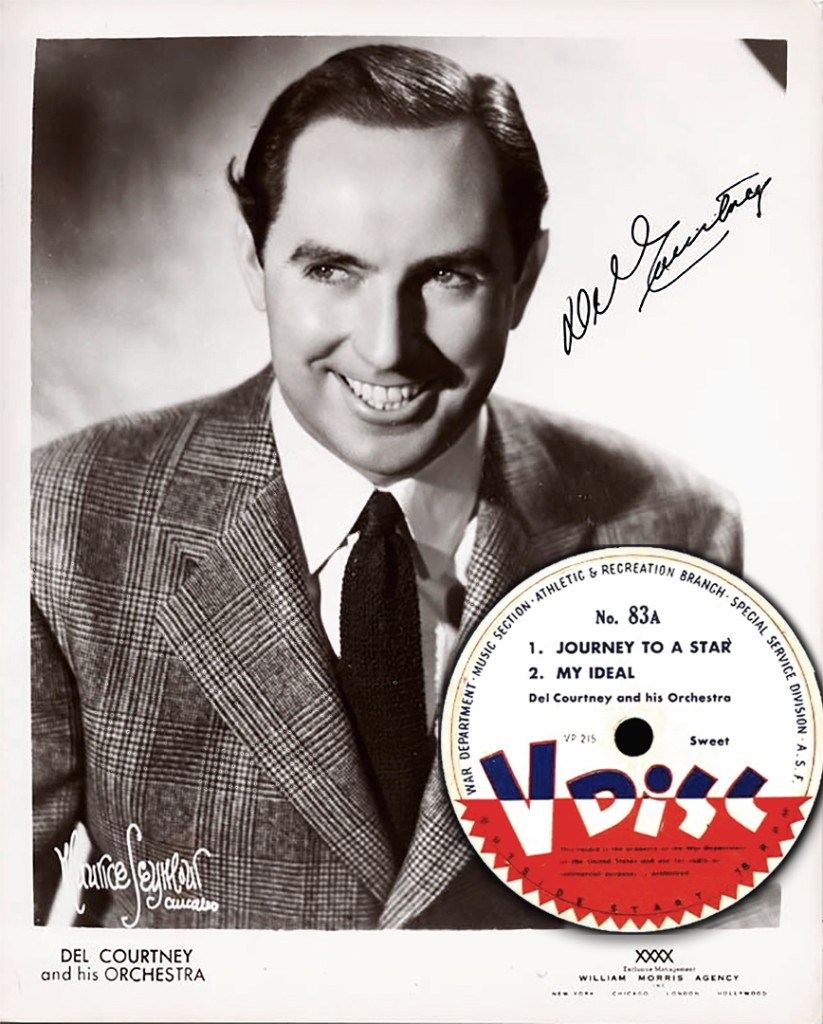

Old Smoothie: Del Courtney

Del Courtney was born in Oakland in 1910. He was a keyboard prodigy by the age of nine, debuting his first dance bands in the 1920s. Making good use of his music degree from the University of California at Berkeley, he succeeded at the top Frisco venues.

Del Courtney was born in Oakland in 1910. He was a keyboard prodigy by the age of nine, debuting his first dance bands in the 1920s. Making good use of his music degree from the University of California at Berkeley, he succeeded at the top Frisco venues.

Known as “Old Smoothie” for his lush Sweet Music style, his orchestras played in the famed Rose Room of The Palace Hotel, for San Francisco Giants major league baseball and Oakland Raiders football. In the 1960s, he broadcast daily from the Tonga Room of the Fairmont Hotel.

Del Courtney was also an actor, appearing on local radio, television and in minor film roles. In 1964 he purchased the innovative radio station KSAN-FM with a partner, before eventually passing in 2006.

The First Lady of San Francisco Radio: Edna Fischer

Born in 1902, piano player, singer and radio personality Edna Fischer was heard on Bay Area radio for more than six decades. She performed at the 1915 Panama Pacific Exposition, broadcast from the 1939 Treasure Island Fair and continued on local radio into the 1980s.

As a toddler Fischer played “Glow-Worm” for refugees arriving in Berkeley fleeing the 1906 earthquake: “I grew up in Berkeley; my family moved there a few weeks before the earthquake in 1906. I was considered a child prodigy – played the piano around the neighborhood before I was old enough to go to school.”

Curiously, most of the San Francisco musicians featured above were piano players. For no particular reason, the region has been a rich source of locally grown or adopted keyboard talent such as Dave Brubeck, Burt Bales, Vince Guaraldi, Peter Clute . . . and Wally Rose.

Wally Rose at the Keyboard

Wally Rose played piano in the Bay Area for more than half a century. He was a local star before, during and after his years with the Lu Watters’ Yerba Buena and Turk Murphy jazz bands, 1940-55. Wally’s Ragtime specialties with Yerba Buena and best-selling piano records inspired a mid-century rebirth of Ragtime music. He performed as a soloist in nightclubs throughout the Bay Area and with symphony orchestras, easily alternating between the concert hall and saloon.

Early in his career, Rose had worked for the cruise lines operating out of San Francisco. Sailing to Hawaii, China and the Far East they offered lucrative jobs, drawing aspiring musicians from across the West. Similarly, the Treasure Island World’s Fair of 1939 attracted skilled performers, setting the stage for the next round of musical transformations at Baghdad-by-the-Bay.

An international port-city, San Francisco was shaped by its libertine boomtown origins, relative isolation and Western outlook. Its individualistic citizenry built a culture of distinctive architecture, food, music and dance.

Part two offers fresh insights on the rowdy Traditional Jazz of Lu Watters and explores the lively “Harlem West” atmosphere of The Fillmore/Western Addition. During the 1950s and ‘60s, North Beach nightlife became a world-class attraction, while Asian entertainers found new expressive freedom in ethnic nightclubs such as Forbidden City.

You may find related video clips on my “Dave Radlauer” Youtube channel. Or please join me on Facebook.

Video clips:

Barbary Coast 1 – Sid LeProtti

Barbary Coast 2 – King Oliver

Barbary Coast 3 – Jelly Roll Morton

“Clem’s Blues” – Clem Raymond (clarinet and scat vocal), Dick Oxtot’d band, mid-1950s

“B-Flat Blues” – Clem Raymond (clarinet and scat vocal), Dick Oxtot’s band, mid-1950s

Barbary Coast TV show trailer

Anson Weeks medley

Bob Crosby with Anson Weeks Orchestra, Rhythm on the Roof, 1934

Ernie Hecksher Orch — The Continental, 1958

Del Courtney V-Disc:

Sweets Ballroom:

“Varsity Drag, “Edna Fischer

“Rag Doll,” Edna Fischer

Bibliography & Sources:

Jazz on the Barbary Coast, Tom Stoddard (Heyday Books, 1982, 1998)

Dangerous Rhythms: Jazz and the Underworld, T. J. English (Harper Collins, 2022)

Review of the above book: https://syncopatedtimes.com/dangerous-rhythms-jazz-and-the-underworld

San Francisco Jazz, Medea Isphording Bern (Arcadia Publishers, 2014)

Sid LeProtti’s Barbary Coast

https://exhibits.stanford.edu/sftjf/feature/sid-le-protti-s-barbary-coast

Clem Raymond Interview – Music Rising, Tulane University

https://musicrising.tulane.edu/listen/interviews/clem-raymond-1958-08-25/

Dave Radlauer is a six-time award-winning radio broadcaster presenting early Jazz since 1982. His vast JAZZ RHYTHM website is a compendium of early jazz history and photos with some 500 hours of exclusive music, broadcasts, interviews and audio rarities.

Radlauer is focused on telling the story of San Francisco Bay Area Revival Jazz. Preserving the memory of local legends, he is compiling, digitizing, interpreting and publishing their personal libraries of music, images, papers and ephemera to be conserved in the Dave Radlauer Jazz Collection at the Stanford University Library archives.