Set forth below is the tenth “Texas Shout” column. It first appeared in the September 1990 issue of The West Coast Rag, now known as The Syncopated Times. It was the initial segment of a two-part article that was concluded in the following issue. It was the first “Texas Shout” essay that required more space than one column could handle, but multi-part articles eventually made up over 15% of the total number.

Set forth below is the tenth “Texas Shout” column. It first appeared in the September 1990 issue of The West Coast Rag, now known as The Syncopated Times. It was the initial segment of a two-part article that was concluded in the following issue. It was the first “Texas Shout” essay that required more space than one column could handle, but multi-part articles eventually made up over 15% of the total number.

Because the text has not been updated, I should mention that, shortly after this column appeared, I moved most of my record reviewing activities to The West Coast Rag in a feature titled “This Month’s Records”. It ran in every issue thereafter until I stopped reviewing records and closed it down in early 1998.

Today I want to talk a bit about reviewing records. Inasmuch as I do not review records for West Coast Rag, perhaps it is appropriate for me to explain to our readers why I feel qualified to talk about record reviewing.

My first published record review appeared in the November 1966 edition of the newsletter of the Toronto-based Ragtime Society. The story of how it came to be written appears in the October 1986 issue of The Mississippi Rag.

In the nearly quarter-century since, I believe that I have had published more reviews of recordings of ragtime, Dixieland jazz and related music than any other U.S.-based writer. All of these reviews have appeared in specialized, small-circulation musical periodicals, including The Second Line, Coda, the now-defunct Jazz Digest and, most particularly, the leading U.S. publication in the field, The Mississippi Rag. My first published review for The Mississippi Rag appeared in the February 1978 issue. During the following dozen years, my reviews have covered over 600 recordings, between one-third and one-half of all recordings reviewed in The Mississippi Rag over that period. On the average, I review over one recording a week, week in, week out, holidays and vacations included.

In the nearly quarter-century since, I believe that I have had published more reviews of recordings of ragtime, Dixieland jazz and related music than any other U.S.-based writer. All of these reviews have appeared in specialized, small-circulation musical periodicals, including The Second Line, Coda, the now-defunct Jazz Digest and, most particularly, the leading U.S. publication in the field, The Mississippi Rag. My first published review for The Mississippi Rag appeared in the February 1978 issue. During the following dozen years, my reviews have covered over 600 recordings, between one-third and one-half of all recordings reviewed in The Mississippi Rag over that period. On the average, I review over one recording a week, week in, week out, holidays and vacations included.

I know of only one stateside readers’ poll in recent years that has focused on Dixieland jazz and has included a category of “Favorite Jazz Critic” — a poll taken a few years ago by Jazzology Records. Participation was limited, but I finished third in the category, behind The New York Times‘s John S. Wilson and The New Yorker‘s Whitney Balliet, both of whom write for periodicals whose circulations dwarf any with which I’m involved.

Maybe the foregoing appears immodest to you, but I’m proud of that resume and it gives me reason to believe that I’m doing something right where reviewing is concerned. Against that background, let’s talk about the role of the record reviewer in today’s Dixieland-ragtime scene.

Maybe the foregoing appears immodest to you, but I’m proud of that resume and it gives me reason to believe that I’m doing something right where reviewing is concerned. Against that background, let’s talk about the role of the record reviewer in today’s Dixieland-ragtime scene.

There are a number of purposes served by record reviews. For example, a review announces the release of a record, much like an ad, so that the artist’s completist-fans can take steps to acquire it.

Because Dixieland is essentially a hobby these days for nearly everyone concerned with it, reviews serve an entertainment function, i.e., they should be written so as to engage the reader’s attention. Some reviewers use their space to present chatty personal anecdotes, or to relate colorful incidents about the artists, composers, etc., as a way of increasing the review’s entertainment value.

A review is a useful tool for educating the readership about what constitutes good Dixieland or where the music came from. Some reviewers take this latter goal to the extreme of spending more time on background than on the music being reviewed. Not long ago I read a review in which the reviewer, believe it or not, used virtually all of his space to cite discographical data about other artists’ vintage recordings of the songs on the record, but failed to supply similar information on the record he was reviewing!

A review serves the purpose of gratifying the ego of the artist, producer or fan in that such persons get the reinforcement, in many cases, of knowing that a supposedly informed writer agrees with their musical tastes. Conversely, if the reviewer fails to provide such reinforcement, some readers consider his comments as nothing less than a personal attack on their values. My files contain, for example, an irate letter from an individual involved with an album to which I had given a favorable review, taking me most severely to task for expressing certain reservations regarding selected portions of the music thereon.

A review serves the purpose of gratifying the ego of the artist, producer or fan in that such persons get the reinforcement, in many cases, of knowing that a supposedly informed writer agrees with their musical tastes. Conversely, if the reviewer fails to provide such reinforcement, some readers consider his comments as nothing less than a personal attack on their values. My files contain, for example, an irate letter from an individual involved with an album to which I had given a favorable review, taking me most severely to task for expressing certain reservations regarding selected portions of the music thereon.

To me, however, the principal purpose of a record review is to give someone who has not heard the record a basis for deciding whether to seek out and purchase the recording. That factor is the one that determines whether what’s being written is a “record review” as opposed to an announcement of newly-issued recordings, a discographical essay, or an historical article.

Dixieland record reviews are less important in that respect than they were in the pre-rock-and-roll era. Back then, most local record stores maintained a broad stock of all types of music. Dixieland musicians did not generally produce their own recordings, so any Dixieland records that were made usually wound up on nationally-distributed labels appearing in the racks of moderately-large stores in good-sized cities.

When I was growing up in Wilmington, Delaware, I had little opportunity to hear Dixieland or ragtime live. (In fact, I was nearly 30 years old before I ever encountered, face-to-face, another pianist who sat down in front of me and played a rag.) Nevertheless, I was able to get a firm grounding in the music because both of my downtown record stores, between them, not only had the major labels, but also such smaller ones as Good Time Jazz (on which my beloved Firehouse Five Plus Two were heard). When the first big shopping mall in town opened, not far from my home, it had a sizeable record store that stocked, among other things, the marvelous series of LP reissues of vintage jazz on the Riverside label.

When I was growing up in Wilmington, Delaware, I had little opportunity to hear Dixieland or ragtime live. (In fact, I was nearly 30 years old before I ever encountered, face-to-face, another pianist who sat down in front of me and played a rag.) Nevertheless, I was able to get a firm grounding in the music because both of my downtown record stores, between them, not only had the major labels, but also such smaller ones as Good Time Jazz (on which my beloved Firehouse Five Plus Two were heard). When the first big shopping mall in town opened, not far from my home, it had a sizeable record store that stocked, among other things, the marvelous series of LP reissues of vintage jazz on the Riverside label.

Handicapped by the then-typical youth’s shortage of funds for as large an investment as an LP ($4.00-$5.00 then), I tried to get as much information as I could about what to buy. Down Beat covered Dixieland for a while, and had some good reviewers. Coda had not yet gone so heavily into modern jazz and could also be relied on. I paid attention to what they said, and eventually, my own tastes started to take shape.

The scene is different now. Except for a very few specialty dealers in isolated spots around the country, most stores rarely stock any Dixieland records. The majority of such recordings today are produced by the artists themselves, and by far the largest portion of all Dixieland record sales are made at the sites of the artists’ personal appearances.

In these circumstances, record reviews play less of a role than they used to. If the crowd is enjoying a performer at a gig, it will step up and buy a record without knowing or caring about what some reviewer may have said about it. Even a highly positive review in a respected Dixieland publication today produces mail-order sales of about twenty copies, hardly a dent in the customary initial pressing of 1,000. (There are exceptions for recordings with unique characteristics — I was told by a producer that a favorable review I wrote of his LP by an extremely popular musician which was published shortly after that musician’s death resulted in nearly 60 orders.)

In these circumstances, record reviews play less of a role than they used to. If the crowd is enjoying a performer at a gig, it will step up and buy a record without knowing or caring about what some reviewer may have said about it. Even a highly positive review in a respected Dixieland publication today produces mail-order sales of about twenty copies, hardly a dent in the customary initial pressing of 1,000. (There are exceptions for recordings with unique characteristics — I was told by a producer that a favorable review I wrote of his LP by an extremely popular musician which was published shortly after that musician’s death resulted in nearly 60 orders.)

So, why bother with reviews anymore if Dixieland record reviews in genre publications aren’t read by very many people and if reviews have little influence on record sales? Is the relevance of reviews further diminished because the recordings themselves are relatively minor purchases, only costing a few dollars, or because in most cases, even their most dedicated devotees don’t take them off the shelf that often even after having owned them for a few months?

Answering for myself, I bother principally because I know there are avid Dixielanders out there who, like me years ago, can’t get to the festivals and gigs where the records are sold, don’t have access to well-stocked stores, and need some help in spending their limited record budgets. I’m still in that position myself regarding European releases; I rely heavily on reviews and ads in certain foreign periodicals in making up my want lists.

Those are the folks I write for. My reviews are aimed at bringing together people who’ve never heard the record, and may never have heard the artist, with recordings that they will feel are worth their money. Conversely, I try to assist people in identifying recordings that they won’t like. Finally, I attempt to do both of those things without regard to my own feelings about the record.

For that reason, I try to include in each full-length review a fairly explicit description of the following items: the style of music that is played (the best Chicago-style recording in the world won’t be welcome in the household of someone who is unalterably wedded to, say, Lu Watters or George Lewis as the barometer of good jazz); the positive aspects of the recording (no matter how bad I may think a record is, the artist has developed an audience or he wouldn’t have made the record — my job is to help that audience realize that this is a record they’ll like); and the negative aspects of the record (I may think the music on a given disc is so good that it overcomes inadequate fidelity, but a hi-fi addict probably won’t).

For that reason, I try to include in each full-length review a fairly explicit description of the following items: the style of music that is played (the best Chicago-style recording in the world won’t be welcome in the household of someone who is unalterably wedded to, say, Lu Watters or George Lewis as the barometer of good jazz); the positive aspects of the recording (no matter how bad I may think a record is, the artist has developed an audience or he wouldn’t have made the record — my job is to help that audience realize that this is a record they’ll like); and the negative aspects of the record (I may think the music on a given disc is so good that it overcomes inadequate fidelity, but a hi-fi addict probably won’t).

Being specific in my descriptions is very important to me. I do not like to read reviews that talk in generalized terms about how great, or how bad, the recording is. Such an approach gives me no help, as a reader, in making my own decision about whether to put the album on my want list.

Thus, I think it is necessary to say in my review, if I like something about a record, exactly what it is I like and why. Similarly, if I dislike something, I feel obligated to indicate fairly clearly what I dislike and why.

Therefore, if I’ve done my job right, I’ve put the reader in a position to make an informed purchasing decision, whether or not he agrees with me. For example, I recently reviewed a recording unfavorably because, in my opinion, much of the music on it was played too fast. The producer later wrote me, in a most friendly way, to tell me that he’s received about a half-dozen orders as a result of my unfavorable review. Obviously, those purchasers considered fast playing to be a plus. If my review helped them find a record they’ll enjoy, I think that’s great, even though the album didn’t do all that much for me.

Related: Texas Shout #11 Reviewing Records, Part Two

Back to the Texas Shout Index.

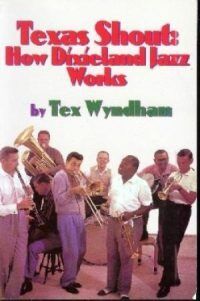

The full run of “Texas Shout” has been collected into a lavishly illustrated trade paperback entitled Texas Shout: How Dixieland Jazz Works. This book is available @ $20.00 plus $2.95 shipping from Tex Wyndham, On request, Tex will autograph the book and add a personalized note (be sure to tell him to whom the note should be addressed).

Tex Wyndham’s 3 CD Guide to Dixieland with music and commentary is available for $20 plus $2.95 shipping. The separate CD, A History of Ragtime: Tex Wyndham Live At Santa Rosa, is available for $13.00 plus $2.00 shipping. On request, Tex will autograph the inner sleeve and add a personalized note (be sure to tell him to whom the note should be addressed).

Send payment to Tex Wyndham, P.O. Box 831, Mendenhall, PA 19357, Phone (610) 388-6330.

Note: All links, pictures, videos or graphics accompanying the Shouts were added at the discretion of the Syncopated Times editorial staff. They did not accompany the original columns and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of Tex Wyndham.

From roughly 1970-2010, Tex Wyndham was: (1) one of the best-known revivalist Dixieland jazz musicians in the US, as cornetist, pianist and bandleader, (2) one of the best-known ragtime pianists in the US, and (3) one of the most respected critics in the US of Dixieland jazz, ragtime, and related music. He is the only person about whom all three of those statements can be made.