Set forth below is the twenty-eighth “Texas Shout” column. It first appeared in the May 1992 issue of the West Coast Rag, (now Syncopated Times.)

Set forth below is the twenty-eighth “Texas Shout” column. It first appeared in the May 1992 issue of the West Coast Rag, (now Syncopated Times.)

In the May 1991 issue of Jersey Jazz, a periodical published by the New Jersey Jazz Society, its excellent editor, Warren Vaché, Sr. (also a fine string bass player) authored one of his typically thoughtful and provocative essays, this one dealing with the selection procedures for a Jazz Hall Of Fame that had been established some years before by the Society. Warren particularly lamented that a number of worthy players from jazz’s earliest years had not yet been enshrined, his selected list of nominees including trumpeters Nick La Rocca and Manny Klein.

I sent in some comments on the matters raised by Warren, which he published in the next issue of Jersey Jazz. Upon rereading my submission, I think that it stands pretty much on its own apart from Warren’s article and that it contains some thoughts which might interest WCR readers. Accordingly, the balance of this month’s “Texas Shout” consists of a reproduction of the text of my letter.

# # # # #

I read with great interest your thoughts in the May 1991 Jersey Jazz regarding the nominating procedure for the Jazz Hall Of Fame. I agree that, comparing the names on your list of nominees with the names that have been selected to date, it appears that the nominators do not have a broad-based view of jazz history.

I think this deficiency is unfortunate. However, it is understandable if one keeps in mind the wrenching changes that jazz has undergone in its brief lifetime.

All styles of jazz require players to have ensemble skills (the ability to improvise meaningfully with other improvising jazzmen) as well as solo skills. However, the emphasis on these skills, as well as the musical vocabulary used for them, has changed drastically over the years.

I have been able to identify seven different pre-swing styles of jazz, each with its own objectives and approaches: the white New Orleans style, sometimes confusingly referred to as the “Dixieland” style, pioneered by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band and carried forward through such combos as the Original Memphis Five and the various Red Nichols groups of the twenties; the downtown Black New Orleans style (exemplified by most of the recordings made in the twenties by Black New Orleans musicians, such as King Oliver, Jelly Roll Morton, Louis Armstrong and Sidney Bechet); Chicago style; hot dance; uptown New Orleans (exemplified these days by The Preservation Hall Jazz Band); West Coast revival; and British trad.

The latter three are revival-period styles. West Coast revival and uptown New Orleans first attracted major attention in the early 1940s, while British trad came along in the late 1950s.

Of these seven styles, six put a higher value on ensemble skills than on solo skills. Only the Chicago style puts a higher value on solo skills than on ensemble skills. (Note again that both skills are always regarded as important — it is the relative emphasis that makes the difference.)

By contrast, all of the other, so-called “advanced” styles of jazz — swing, mainstream (improvised small-band jazz played by swing musicians), progressive, bop, etc. — put a higher value on solo skills than on ensemble skills. Further, while the onset of swing changed this emphasis, the development of bop, with its deliberate rejection of much of the preceding vocabulary of jazz, introduced a further radical change in emphasis — the reharmonization of tunes to use higher chords, the utilization of step-wise chord progressions vs. the more typical circle-of-fifths, the superimposition of jagged melodic phrases above the normal four-bar phrase length and the like.

The effect of these changes is that jazz has been divided into three fairly large bodies, each with its own rules. As you move from pre-swing styles into swing-era styles, you need to adjust your values from ensemble orientation to solo orientation, and as you move beyond swing into the”modern” styles, you need to make an adjustment to your ears to accommodate the very different sounds you’ll encounter.

Most people can’t or won’t make those adjustments. Very, very few jazz fans are able to say honestly that they appreciate Dixieland, swing, and bop in equal measure.

That, I think, is the difficulty with having one panel of experts to nominate names for a Hall of Fame. If you believe that jazz really started with Charlie Parker, you are very likely to consider jazz based on a Dixieland vocabulary as being simplistic, dated, crude and noisy. Conversely, if you believe that, after Jelly Roll Morton, jazz degenerated into a bunch of soloists playing as high and as fast as possible, you will probably think that Dizzy Gillespie belongs in a Hall of Infamy rather than the reverse.

I am not surprised that the Hall of Fame sponsored by the New Jersey Jazz Society contains musicians who, by and large, reflect the general Chicago/mainstream/ swing taste of the Society’s membership and officials. However, if a truly balanced Hall of Fame were desired, you might be more likely to get it by having three different panels make the nominations.

One panel would be comprised of “experts” whose main area of interest was in jazz styles based on the twenties styles, including revival styles thereof. The second would deal with musicians of a post-twenties, pre-bop persuasion, covering swing, mainstream, jump and, maybe, progressive. The third would cover bop, free and other styles of”modern” jazz. Anyone qualified in more than one area, of course, could serve on more than one panel.

In that manner, names of musicians such as the ones nominated in your article could get consideration by experts who understand them, and so could such equally worthy names as Lu Watters and Thelonious Monk. As things now stand, I think it would be nearly impossible to assemble a panel of jazz experts that would be likely to vote in the same year to place, say, a Miles Davis, a Nick La Rocca and a Manny Klein into a Jazz Hall of Fame.

As a related point, many of the “experts” involved in making such selections tend to see jazz as always moving forward. For that reason, they are inclined to downplay major changes in the field that occur in older styles of jazz.

If, however, changing the course of a given stream of jazz qualifies you for consideration in a Hall of Fame, as I think it should, then musicians who choose to work in older styles should be recognized for such accomplishments. The same statement can be made of musicians who have exerted a wide influence on the playing of other musicians.

As a case in point, the two most widely imitated clarinetists in all of jazz today have to be Benny Goodman and George Lewis. Partly because Goodman was on the cutting edge of jazz in his day, everyone is willing to rush him into his deserved place in the jazz pantheon. However, Lewis began recording during the revival period of Dixieland, a factor which, in some people’s minds, diminishes his claim to the same honor.

Similarly, the three most widely imitated trombonists in pre-swing jazz are, virtually beyond question, Jack Teagarden, Jim Robinson and Turk Murphy[*]. With so many musicians around the world trying as hard as they can to imitate them, Robinson’s and Murphy’s influence continues in a measure well beyond that of many musicians routinely put forward as potential immortals. Whether one prefers their styles or not, Robinson and Murphy left their marks in a way that few jazzmen did. They deserve recognition for that very significant accomplishment.

How many jazzmen have, virtually single-handedly, created styles of jazz that took hold and inspired disciples who preach their gospels decades later? Lu Watters did, founding the West Coast revival style of Dixieland. So did Ken Colyer, working in tandem with Chris Barber regarding British trad.

Personally, in addition to the names you list, I can think of seven revival period musicians whose impact on jazz was so powerful that, under any reasonable criteria for selection, each ought to be in a Jazz Hall of Fame: Bunk Johnson, George Lewis, Jim Robinson, Lu Watters, Turk Murphy, Ken Colyer and Chris Barber. I would think that a jazz buff who has devoted as much time to swing styles, or “modern” styles, as I have to Dixieland styles would be able to come up with a comparable list of names in those styles that cry out to be enshrined.

I doubt that the present procedure has a chance of giving balanced consideration to many such jazzmen. However, as I’ve said before, it’s NJJS’s Hall, so NJJS and its members are really the only ones that need to be happy with the selections. If I ever open my own Hall, though, Turk will be in it and (much as I dislike “modern” jazz) so, probably, will Ornette Coleman.

# # # # #

[*] Warren added an Editor’s Note to my letter, observing that many other trombonists have been highly influential on their successors, that all jazzmen borrow from each other, and that most players, quite properly, avoid deliberate imitation in favor of selectivity from various available sources. I couldn’t agree more. I believe that deliberate imitation is a musical dead end and that the better players recognize a need to go beyond mere imitation.

Nevertheless, there is a certain amount of imitation in jazz. With regard to Dixieland trombone, I see Turk, Big Jim and Tea clearly leading the pack in terms of numbers of conscious out-and-out imitators. Whether imitation is desirable or not, if a musician does inspire a significant group of imitators, that factor tells me that he is impacting the music to a degree that his name ought to be considered when Hall of Fame nominations are being discussed.

Back to the Texas Shout Index.

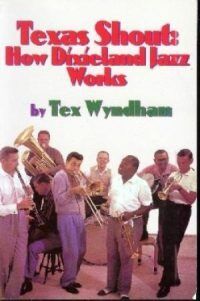

The full run of “Texas Shout” has been collected into a lavishly illustrated trade paperback entitled Texas Shout: How Dixieland Jazz Works. This book is available @ $20.00 plus $2.95 shipping from Tex Wyndham, On request, Tex will autograph the book and add a personalized note (be sure to tell him to whom the note should be addressed).

Tex Wyndham’s 3 CD Guide to Dixieland with music and commentary is available for $20 plus $2.95 shipping. The separate CD, A History of Ragtime: Tex Wyndham Live At Santa Rosa, is available for $13.00 plus $2.00 shipping. On request, Tex will autograph the inner sleeve and add a personalized note (be sure to tell him to whom the note should be addressed).

Send payment to Tex Wyndham, P.O. Box 831, Mendenhall, PA 19357, Phone (610) 388-6330.

Note: All links, pictures, videos or graphics accompanying the Shouts were added at the discretion of the Syncopated Times editorial staff. They did not accompany the original columns and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of Tex Wyndham.

From roughly 1970-2010, Tex Wyndham was: (1) one of the best-known revivalist Dixieland jazz musicians in the US, as cornetist, pianist and bandleader, (2) one of the best-known ragtime pianists in the US, and (3) one of the most respected critics in the US of Dixieland jazz, ragtime, and related music. He is the only person about whom all three of those statements can be made.