Set forth below is the thirty-first “Texas Shout” column. It first appeared in the August 1992 issue of the West Coast Rag (now The Syncopated Times).

Set forth below is the thirty-first “Texas Shout” column. It first appeared in the August 1992 issue of the West Coast Rag (now The Syncopated Times).

Because the text has not been updated, I should mention that some of the people who supplied information for this article, and who are named therein, are, sad to say, no longer among the living. Also, the performances cited as appearing on Good Time Jazz LPs have since been reissued on CD.

One of the most important recording dates of the Dixieland revival, the session which first focused attention on the uptown New Orleans style, took place on June 11, 1942 in the third-floor piano storeroom of Grunewald’s Music Store in New Orleans. It marked the recording debut of veteran trumpeter Bunk Johnson, backed by a band which, in the late 1950s under the leadership of its clarinetist George Lewis, went on to achieve worldwide popularity and lasting influence.

One of the numbers recorded by Johnson on that historic occasion was an old pop tune that has gone on to be a great favorite of West Coast revival-style combos. In attendance was David Stuart who, in the liner notes to a 1962 reissue of these sides, Good Time Jazz M12048, said of this particular selection:

“Storyville Blues” was the third number. The tune has been recorded since under several titles. “Storyville” was chosen because it’s a good honest word and as far as I know hadn’t before been used as a song title.

Thus, we know that the piece now widely played under the title “Storyville Blues” did not start out with that appellation. For those who are interested, I’d like to spend the balance of this column sharing with you such information as I’ve been able to gather regarding the origins of this now-familiar anthem.

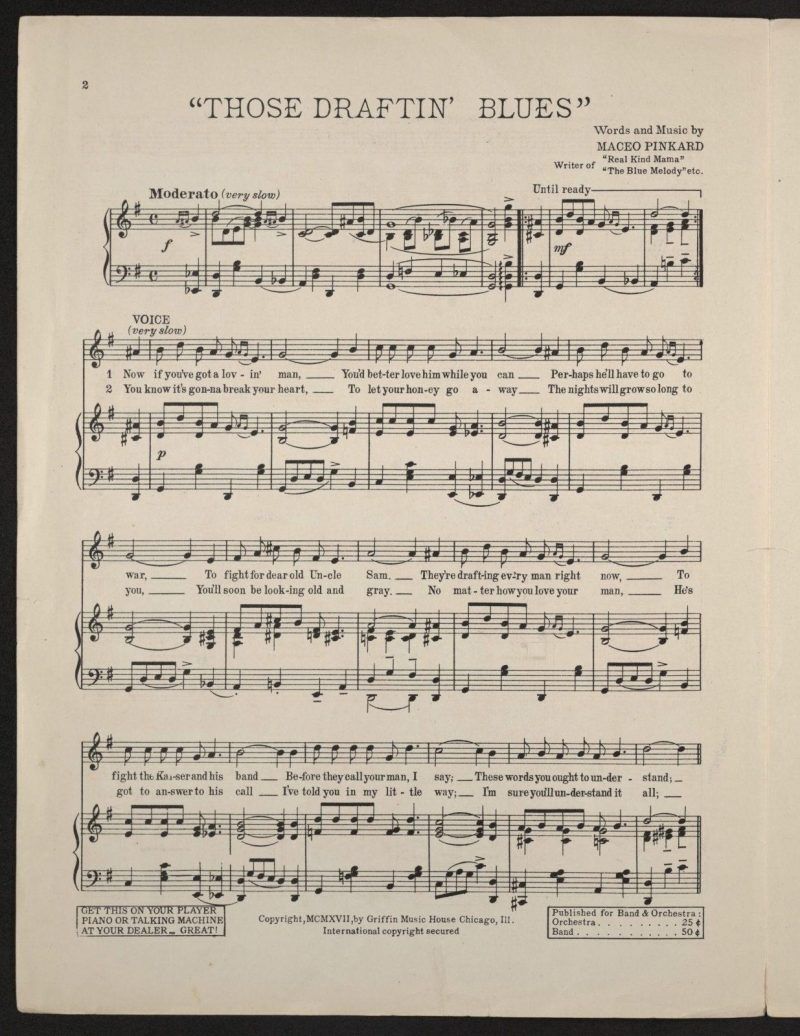

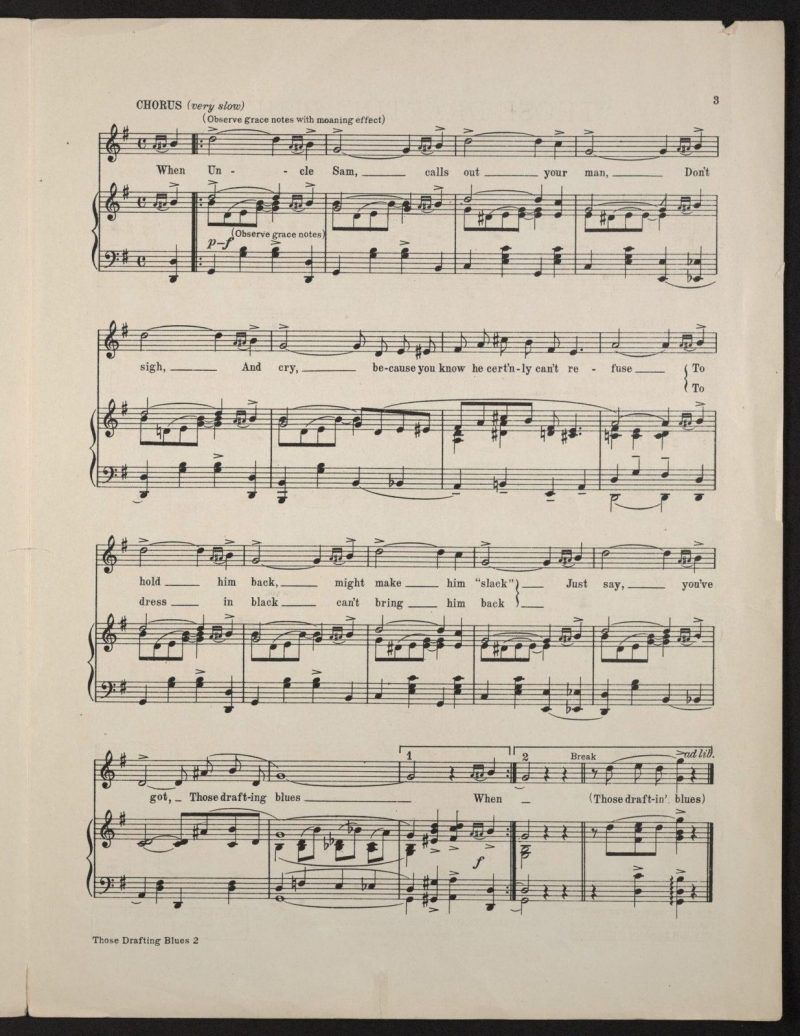

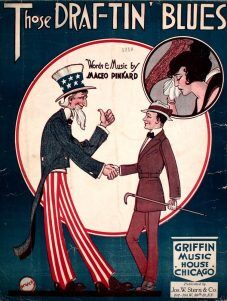

Acting on a tip I got years ago, from (if memory serves) sheet music collector and piano-roll expert Mike Montgomery (but it might have been Thornton “Tony” Hagert) at a Ragtime Society Bash in Toronto, I went looking for a piece of sheet music called “Those Draftin’ Blues.” The cover and both pages of the music are reproduced alongside this column.

Examination of this material shows beyond question that it is indeed “Storyville Blues.” The differences between “Those Draftin’ Blues” and the customary way of playing “Storyville Blues” are so trivial as to be insignificant – easily attributable to lapses in Bunk Johnson’s memory (which subsequent research has shown to be highly suspect in a number of respects).

The song sheet credits the 1918 tune to Maceo Pinkard, a successful Tin Pan Alley denizen whose works are still heard on the jazz scene. He is the composer or co-composer, for example, of such standard Dixieland tunes as “Sweet Georgia Brown,” “Sugar,” “(I’ll Be A Friend) With Pleasure” and “Them There Eyes.”

It wasn’t easy to turn up a copy of “Those Draftin’ Blues.” The song is not a common item to find on music dealers’ lists, a fact which implies that it was not popular and did not sell in large numbers.

An analysis of the sheet music reveals why the tune might not have been a hit. To be popular, a song has to contain an effective combination of lyric and melody. The lyric to “Those Draftin’ Blues,” even after allowing for the heated patriotism found in many ditties from the World War I days, is rather downbeat and somewhat maudlin. Moreover, its melody, consisting in large part of long notes within the chords, mounted on a plain-vanilla chord progression, can hardly be called inspired.

I make the foregoing points not to disparage “Those Draftin’ Blues” as a jazz tune. The qualifications for a composition to be a good jazz vehicle do not coincide with the requirements for success as a pop tune.

(As an aside, quite a few tunes that we regard today as staples of the jazz repertoire did not make it in the popular market. One such title that comes readily to mind is “China Boy.” The reprint copy in my collection suggests that “China Boy” was originally a pseudo-oriental lullaby, meant to be played slowly. In fact, its never-heard verse couldn’t breathe if played at the heady pace typically used for “China Boy” today.

It seems unlikely that “China Boy” was a commercial success as a pop song. Copies are so rare that, in thirty years of collecting sheet music, I have never seen an original edition of it, nor has an original ever turned up on any of the lists regularly sent to me by dealers. Yet, I doubt that there is a sizeable Dixieland festival that takes place in the U.S. today at which “China Boy” isn’t played at least once.)

My reason for observing that “Those Draftin’ Blues” is not a remarkable piece of composition relates to the effort to trace the tune to its roots. Once we’ve located its first publication, we can ask ourselves if there is anything that precedes the song sheet – that is, did Maceo Pinkard write this tune, or does it have some pre-existing life that Pinkard appropriated, much as W.C. Handy (as Handy freely admitted) adopted melodies he heard from itinerant singers into his world-famous blues?

My reason for observing that “Those Draftin’ Blues” is not a remarkable piece of composition relates to the effort to trace the tune to its roots. Once we’ve located its first publication, we can ask ourselves if there is anything that precedes the song sheet – that is, did Maceo Pinkard write this tune, or does it have some pre-existing life that Pinkard appropriated, much as W.C. Handy (as Handy freely admitted) adopted melodies he heard from itinerant singers into his world-famous blues?

Because “Those Draftin’ Blues” is a relatively ordinary work from the viewpoint of musical structure, and because Pinkard is known to have composed several other more successful and imaginative numbers, I have no trouble reaching the following conclusions: (1) Pinkard had no need to “steal” this fairly commonplace idea. (2) He was certainly capable of writing something at or above the level of inspiration found in “Those Draftin’ Blues.” (3) The composition does, most likely, start with him.

Having formed those views, I’ll turn to the persistent rumor, which I’ve seen from time to time (most recently in an article in the June 1991 West Coast Rag), that the “Storyville Blues” theme can be traced back to 1897, that it originated in New Orleans, and that it is attributable to Tom Turpin, the great ragtime pianist from St. Louis. Personally, I have never believed the Turpin attribution – the musical structure of “Storyville Blues” is totally unlike any portion of Turpin’s authenticated compositions of which I’m aware.

However, to dispose of this question, I called my friend Trebor Tichenor, a world-class expert on piano rolls and ragtime sheet music, the excellent pianist for the St. Louis Ragtimers, and probably the foremost authority on the activities of St. Louis-based turn-of-the-century ragtimers. I called Treb at the right time, because he was just putting to bed a book on Turpin, projected for eventual publication by the Smithsonian.

Treb had also heard that Turpin has been put forth as having written the “Storyville Blues” theme, but he does not believe this claim. Treb has never found any evidence tending to substantiate Turpin’s authorship. Further, Treb agrees with me that the tune is stylistically at odds with the musical portrait of Turpin emerging from Turpin’s other established works. In the absence of concrete evidence to the contrary, Treb’s opinion on this point is good enough for me.

With regard to the alleged New Orleans origins of the “Storyville Blues” theme, I called another friend, Al Rose, author of several major volumes of jazz lore and probably the definitive voice on early Crescent City jazz tunes. Al said that, to his knowledge, the tune has no New Orleans connection and that he knows of no reason why it should not be thought of as having been written by Maceo Pinkard at the time of its publication in 1918. Again, unless someone comes up with something more solid than hearsay and speculation, Al’s pronouncement on this matter ends the discussion as far as I’m concerned.

At this point, we’ve concluded that the correct title for “Storyville Blues” is “Those Draftin’ Blues” (and I think it should be played under that title going forward), that it was not written by Tom Turpin, and that it was written by Maceo Pinkard for publication in the song sheet that illustrates this column. Having done so, we need to examine another loose end about the tune.

Most contemporary renditions of the number end with a variation on the chorus that begins each phrase with a series of ascending half-notes played in a crescendo. This chorus does not appear in the original sheet music (nor, Trebor informs me, in Maceo Pinkard’s piano roll of “Those Draftin’ Blues”). Where did this chorus come from?

Oddly enough, the general genre discographies are not usually indexed by song title. However, my examination of three references that are, Roger Kinkle’s The Complete Encyclopedia Of Popular Music 1900-1950 and Brian Rust’s discographies of jazz records and of British dance bands, produces only two citations to issued vintage-period records of “Those Draftin’ Blues.” The first is a 1918 side by Wilbur Sweatman and the second is a 1940 rendition by Skeets Tolbert. I have not heard them, so I don’t know if either contains the crescendo chorus.[*]

Although I can’t be certain that there are no others, I believe the next three recordings of this theme are Johnson’s 1942 version; Lu Watters’ Yerba Buena Jazz Band’s 1946 version (which was titled, for reasons discussed below, “Bienville Blues”); and Turk Murphy’s Jazz Band’s 1950 version (reissued on Good Time Jazz L-12027). I have all three in my collection. The first two do not contain the crescendo chorus, but Turk’s does.

I have seen it said somewhere, although I can’t recall the reference (but I do remember that no supporting evidence was given for the statement), that Turk Murphy wrote the crescendo chorus. In an attempt to nail this point down, with the generous assistance of clarinetist (and leader of the Zenith Jazz Band) Earl Scheelar, I put the question to Turk’s widow, Harriet, and the following alumni of Turk’s combo: Bob Helm, Wally Rose, Pete Clute, Bill Carroll, Bill Armstrong and Jim Maihack.

Of those who had any opinion on the subject, all believed that Turk wrote the crescendo chorus. However, as reported below, only Jim Maihack was able to cite an instance in support of that view from his own first-hand knowledge. (To be precise, Bob Helm was uncertain when first asked – by Earl – but when I asked him again a few weeks later, Bob was willing to say definitely that Turk wrote the crescendo chorus. I’m not sure, in light of the sequence of events, how much weight to give Bob’s second try.)

Jim told me of one occasion when Turk described a conversation some years ago between himself (Turk) and Ward Kimball, trombonist/leader of the Firehouse Five Plus Two. In that discussion, Kimball told Turk that the FH5 had recently waxed an album made up entirely of traditional material. Turk concluded his story by saying to Jim words to the following effect: “I didn’t have the heart to tell Ward that I had written that one part of ‘Storyville Blues’ myself.” (Incidentally, the recording Kimball referred to was released as Good Time Jazz M12040, entitled “Dixieland Favorites”; it includes a 3/21/60 performance of “Storyville Blues” played with the crescendo chorus.)

Even without regard to the foregoing anecdote, looking at the question from a purely musical viewpoint, I am prepared to believe that Turk is the composer of the crescendo chorus. At the same 5/8/50 session at which his band first waxed “Storyville Blues,” Turk also recorded “By And By.” On the latter number, the band plays an eight-bar interlude in which the horns are voiced in whole and half notes, much like the crescendo chorus of “Storyville Blues.” This eight-bar interlude does not appear in my two hymn-book editions of the music to “By And By” (which are titled “When Morning Comes” and “When The Morning Comes”). These circumstances suggest to me that Turk wrote the eight-bar interlude, and that he did the same sort of thing for its session-mate, “Storyville Blues.”

For whatever it’s worth, the rideout on Turk’s performance of “See, See, Rider” on Columbia CL 650 is a variation which, as far as I know, had not appeared in any previously recorded version of the tune. It is a chorus in which the horns play a climbing figure in harmony. To me, this “See, See, Rider” finale, which I’d guess that Turk wrote, bears stylistic similarities to the crescendo chorus of “Storyville Blues.” Thus, I’m satisfied to credit the evidence supplied by Jim Maihack and to attribute the “Storyville” crescendo to Turk.

As a postscript, I asked Helm and Rose, who were on the Watters 78, how Watters came to play the number under the title “Bienville Blues.” Both were sure that Turk had picked the title, but neither could recall why.

Jim Maihack also supplied that missing piece. Turk told Jim that he (Turk) picked the title from a map of New Orleans’ French Quarter and used it on a whim to see what would happen. He (Turk) added that, sure enough, a few years later another band did record the tune as “Bienville Blues.”

What questions remain? Well, I am a bit puzzled by Stuart’s 1962 comment, quoted above, that, since Johnson’s 1942 recording, “the tune has since been recorded under several titles” (emphasis added). Between 1942 and 1962, to my knowledge, it was recorded under only two titles, “Storyville Blues” and “Bienville Blues.” I wouldn’t think that two instances are enough to constitute “several,” but maybe I’m being too picky over Stuart’s phrasing.

Anyway, if you’re still awake, you now know as much as I do about “Those Draftin’ Blues/Storyville Blues/Bienville Blues.” I would be very interested in knowing if there is any additional reliable first-hand or documentary evidence on this subject.

*After this column was published, I received communications from two generous readers, Pete Pepke and Don McGrath, confirming that the crescendo chorus does not appear on either the Sweatman or the Tolbert 78.

Back to the Texas Shout Index.

The full run of “Texas Shout” has been collected into a lavishly illustrated trade paperback entitled Texas Shout: How Dixieland Jazz Works. This book is available @ $20.00 plus $2.95 shipping from Tex Wyndham, On request, Tex will autograph the book and add a personalized note (be sure to tell him to whom the note should be addressed).

Tex Wyndham’s 3 CD Guide to Dixieland with music and commentary is available for $20 plus $2.95 shipping. The separate CD, A History of Ragtime: Tex Wyndham Live At Santa Rosa, is available for $13.00 plus $2.00 shipping. On request, Tex will autograph the inner sleeve and add a personalized note (be sure to tell him to whom the note should be addressed).

Send payment to Tex Wyndham, P.O. Box 831, Mendenhall, PA 19357, Phone (610) 388-6330.

Note: All links, pictures, videos or graphics accompanying the Shouts were added at the discretion of the Syncopated Times editorial staff. They did not accompany the original columns and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of Tex Wyndham.

From roughly 1970-2010, Tex Wyndham was: (1) one of the best-known revivalist Dixieland jazz musicians in the US, as cornetist, pianist and bandleader, (2) one of the best-known ragtime pianists in the US, and (3) one of the most respected critics in the US of Dixieland jazz, ragtime, and related music. He is the only person about whom all three of those statements can be made.