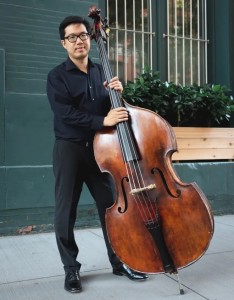

Judged by looks alone, Joe Temperley did not live up to any cliché of a jazz musician. Rather, he looked like a successful businessman, always well dressed with a reserved demeanor, who just happened to have a baritone saxophone draped over his chest. When approached he was always affable and with a warm smile. To Wynton Marsalis, he was “the most soulful thing to come out of Scotland.”

He was from a small Scottish town and while his parents were non-musicians, his influential older brother encouraged him to play the cornet and later the saxophone. He was a fast learner and soon earned spots in some of the best dance bands first in Scotland, then in Great Britain. He regarded as the apex of those years his almost decade long employment with Humphrey Lyttelton, whom he considered a close friend and important to his own artistic development.

Temperley fondly said of Lyttelton, “He was a brilliant, well-educated man, schooled at Eton and an officer in the Guards. He was very humorous. claiming that because his long-lost relative Oliver Lyttelton was involved in the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 (to blow up Parliament and kill the king), he was hung, drawn and quartered then buried in Surrey, Buckingham, Wiltshire and several other counties.”

A significant force in jazz on his own, the English band leader appreciated the importance of exposing his musicians to American jazz giants. When the Duke Ellington Orchestra toured England, Lyttelton arranged to have himself and his men attend most of their performances. Temperley not only meet his long-time hero Harry Carney, but spent enough time with him to develop a real friendship. That might have gotten him fired for almost missing one of Lyttelton’s gigs.

“What happened was I spent the whole day with Harry. He was in the Dorchester Hotel and had about five or six bottles of scotch on the shelf. We had a few drinks and got to talking and all of a sudden, I realized I was about an hour and a half late. When I got there, I was the best part of two hours late. So, Humph said, ‘Where have you been?’ I said, ‘I’ve been with Harry Carney.’ And he said: ‘Oh…well that’s educational.’ That’s how he dealt with it. He was a wonderful man. I loved him dearly.”

The Lyttelton’s band 1959 American tour brought Temperley here for the first time. In spite of the August heat, which he was not used to, the great Scot fell in love with New York and wanted to come back. He told his friend that he was moving to New York, even though he had nothing there waiting for him. Lyttelton understood. “He half expected it because I’d been with the band a long time and I wanted something different and I couldn’t see that happening in London. When I finally left the band, he gave me fifty pounds in an envelope and said: ‘Here, this is in lieu of a gold watch.’ That was a beautiful thing as fifty pounds was a lot of money then.”

In 1965, Temperley arrived with little prepared for him. “I had some American friends like Buck Clayton, Jimmy Rushing, and Harry Carney, but they were traveling and busy with their own careers. I was literally on my own, and it was Christmas.” He quickly got a job—selling radios in a department store, “… because I had to wait six months to get in the union. But at the end of the six months, Jake Hanna and Nat Pierce helped me get a seat in the Woody Herman band, and I went on the road with Woody for eighteen months.”

“That was quite a change from what I was used to. When you’re with a band in London and you’re on tour, you’re never more than two or three days out; you do three or four jobs and come back because it’s only a couple of hundred miles from wherever you are. Here our first job was in Kansas City, and I had to fly out. So, I found myself in all kinds of different places, and it was strange, but it was a wonderful experience to play with Sal Nistico, Joe Romano and Carmen Leggio in the saxophone section.”

Woody Herman personally seemed to thrive by being on the road, however the constant travel wore Temperley down and he left the band after about two years. Also, in New York he had numerous offers to choose from. “I didn’t want to travel any more after Woody. I wanted to rest from that. I worked a lot with Thad Jones and Mel Lewis to sub for Pepper Adams. Then Pepper’s mother got sick and he went back to Detroit, so I was a permanent sub in the band for three years, and I was always a sub with Buddy Rich’s band when they needed a baritone player.” The great drummer even tempted him temporarily back on the road. “I went to Canada with Buddy, but that was a saxophone section with Lew Tabackin, Eddie Daniels, Joe Romano, Sal Nistico and me. And Buddy was so great, He took us out for dinner every night, he was wonderful to us.”

Like so many other jazz artists, Temperley also spent time in the pits of Broadway. That was not only steady work with benefits, but it was also a way to meet more fellow musicians like Earl May, who became another good friend, and Al Cohn. “He was a very funny guy and intelligent as well. He could do the New York Times Sunday crossword puzzle in 10 to 15 minutes. One time I was in a recording studio with Ralph Burns, and Ray Charles came in. He said, ‘Ralph did the arrangement for my biggest hit “Georgia on My Mind.”’ He didn’t know that Ralph had farmed out the arranging to Al Cohn, so Al was responsible for it.”

When Harry Carney died in 1974, Joe Temperley performed “Sophisticated Lady” at his friend’s funeral. Mercer Ellington, who was by then leading his late father’s orchestra, was there and took notice. Temperley was soon in the Ellington organization playing the Carney charts. He continued to do so on and off for a decade.

When Wynton Marsalis formed the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, he wanted to focus on the Ellington canon. He filled it with many of the surviving Ellington alumni such as Britt Woodman, Noris Turney, Jimmy Woode, and Jimmy Hamilton as well as stellar sidemen of similar fame such as Frank Wess. He also asked Temperley, and Temperley found it an irresistible offer. The great Scot gave Mercer his notice, joined the JLCO and remained there for twenty-six years.

The organization behind the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra is a phenomenal entity that does far more than promote live jazz concerts. Its New York City home is to jazz what Carnegie Hall is to classical music – a setting fit for the spirit of its great band. The musicians are not just artistically excellent, they also have compatible personalities, and tend to stay for many years. Temperley explained, “Our band is very communal. We have softball games and football games, barbecues and things like that. There’s a lot of love and respect in our band. Everybody just hangs out with everybody else. I don’t participate in the sports events. I just monitor the arguments.”

Marsalis was the driving force for both the band and its impressive home. “I’m just so proud of Wynton for doing what he did,” Temperley said. “He doesn’t get the recognition he deserves about it.” Marsalis did everything he could to ensure everyone had an emotional commitment to the excellence of the new facility. As it was being built, “We watched it develop. We made periodic visits where we’d assemble, don hardhats and go in to see the creation of it all. It was fantastic to see it grow. We actually went at Christmas and played in the middle of all this scaffolding and things. We played for all the construction workers, we had a lunch spread out and we played all kinds of Christmas music for them. We did that several times.”

While Marsalis called Temperley, “The anchor and foundation of our orchestra,” the great Scot was probably best known for his tender and soulful playing of Ellington’s “The Single Petal of a Rose.” I’ve seen him bring tears to the eyes of his bandmates by his emotional renditions of it. He would use the bass clarinet with only a pianist accompanying him. One woman was so moved by it that she hired him and pianist Dan Nimmer to play it for her upcoming wedding in Paris, France. “She flew my wife and I first class and put us up for five nights in a hotel to play this one song at her wedding; which was a fairytale kind of thing.”

On another occasion he received a heartbreaking letter from another woman. “She wrote about her son who played bass clarinet. He was seventeen years old and took his own life last year. She felt that I played that tune and it was a message from her son through me to her. It was an emotional letter for me. The same song, it can be joyous or sad, it’s that kind of a piece.”

The renowned saxophonist was also dedicated to passing on his knowledge. As fellow JLCO section mate, Ted Nash recalled, “I first had the opportunity to play with Joe when I was still a teenager. We were playing a Duke Ellington piece with the National Jazz Ensemble, and I was playing lead alto with that teenage energy and Joe just stopped and said, ‘This is Duke Ellington. This is not rock and roll.’ But I didn’t need to hear his words. Just sitting in the section with him and hearing his spirit and soul and the way he approached music taught me so much over the years.”

Generous, but with a burly and intimidating figure, he proved to be a formidable educator at the Manhattan School of Music and at Juilliard. A former student told me that some students fondly called him “Bad Temperley.” He was proud that many of his students built successful musical careers. Indeed, one of them, Paul Nedzela succeeded him in the JLCO.

Year after year Temperley was usually the first to arrive for a gig and the last to leave the stage when it ended. As his health declined, he retired. The organization honored him several times and in several ways. At the conclusion of his last regular gig, as usual, the frail-looking figure gathered his things as most of the musicians left the stage; but this time all of the other saxophonists waited and exited with their ailing friend.

For a special JALCO concert, entitled “Celebrating Joe Temperley,” Mr. Marsalis composed a three-part suite entitled “Joe’s Concerto” in his honor, and several bandmates spoke movingly about him. Fittingly the event lasted about two hours, and as I write it’s still on YouTube.