Bandleader Ada Leonard was a dancer, singer and show business professional who led the first all-female Swing orchestra touring Army training camps during WWII filling the sustained demand for Swing music. Recently, keen interest has arisen about these so-called “all-girl” orchestras. Note that the term “girl,” meaning “woman,” is used here in its historical context.

‘The Sultry Siren of Swing’

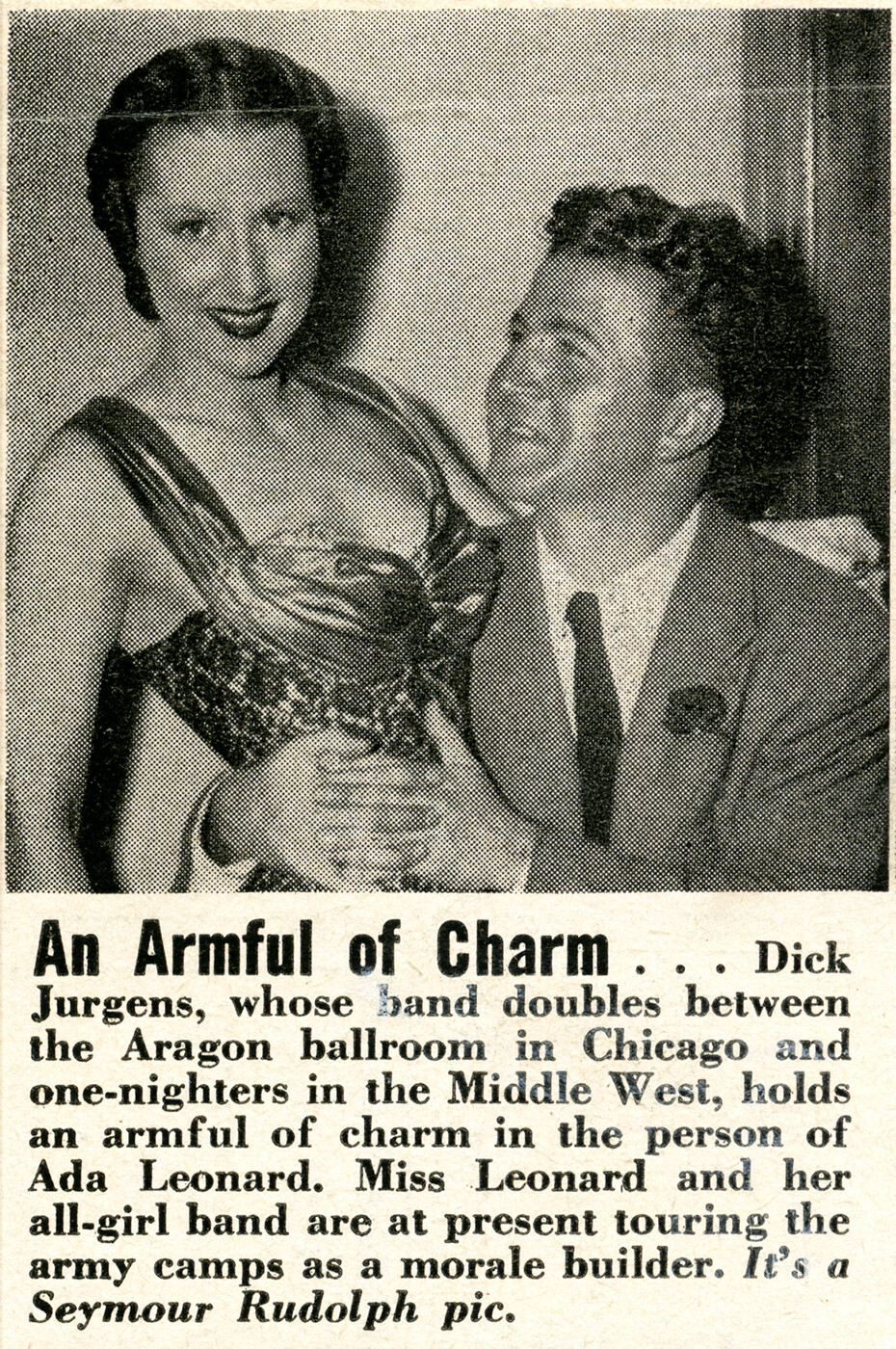

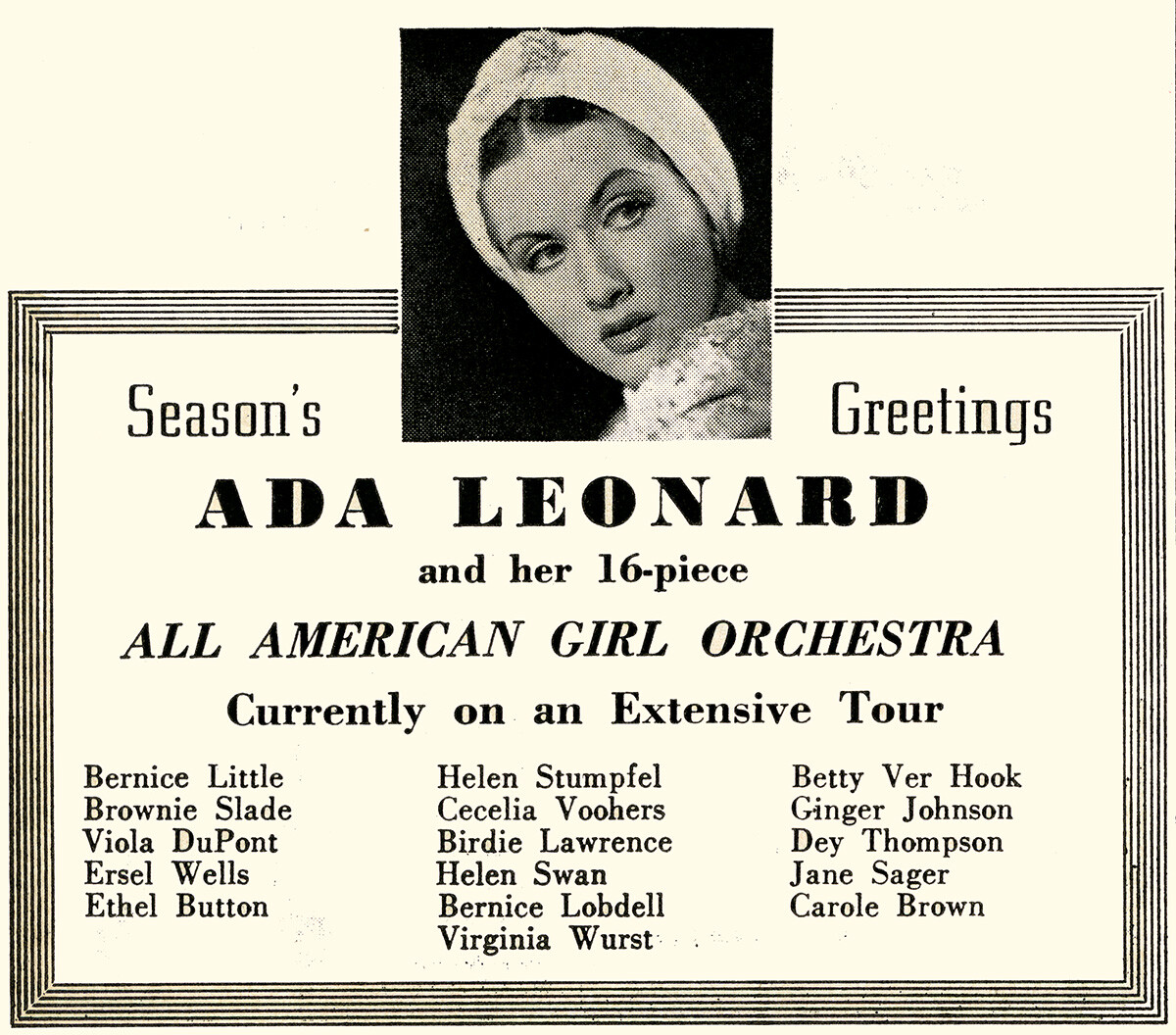

Forgotten today, Ada Leonard (b. Lawton, OK 7.22.15 – d. Santa Monica, CA 11.29.97) was an experienced entertainer and former exotic dancer. Her 16-piece orchestra was the first of about 100 all-female ensembles that toured Army training camps sponsored the USO (United Service Organizations).

Leonard had been a strip tease dancer. That’s what everyone KNEW about Ada, that she was a former “Burlesque Queen.” Bear in mind that stripping was actually quite modest in those days. Viewers were convinced they were seeing more than was revealed, as in the demure burlesque routine of Gypsy Rose Lee performed in the 1943 movie, Stage Door Canteen.

Billed as “The Sultry Siren of Swing,” she didn’t take the moniker seriously, making a fine art of being UN-glamorous offstage according to her former associates. When off duty she went incognito, wore no makeup, “frumpy” clothing and “basked in sloppiness” reading her favorite Popeye comic books. Admirers asking her whereabouts were told, “Oh, she’ll be along soon . . . in a limousine.”

In their one short film performing “(Back Home Again in) Indiana” the orchestra is spirited and competent. But it’s a precursor and not her actual band. Leonard had been hastily grafted onto the ensemble late in its development.

Conductor’s baton in hand, she engages the camera more than her musicians, gliding and wriggling suggestively consistent with contemporaneous reports. She soon took charge, leading her All-American Girl Orchestra through three coast-to-coast tours of USO-Shows and marquee commercial venues, 1941-45.

A Strategic Reserve of Glamor

In the 1930s, “all-girl” orchestras were novelties associated with an actress, dancer or impresario like Phil Spitalny. But they became a necessity as men went off to war and the supply of male musicians available dwindled. The disruptions of WWII generated opportunities formerly closed to women, who briefly achieved acceptance as instrumentalists and hot musicians in dance bands, the Hollywood studios and radio orchestras.

Excused from travel-related rationing, all-women orchestras toured the country, delivering a strategic reserve of Swing. These so-called “all-girl” orchestras made almost no records or films; even photographs are quite rare. Their formerly obscure identities and stories have only recently emerged in books, oral histories and documentaries.

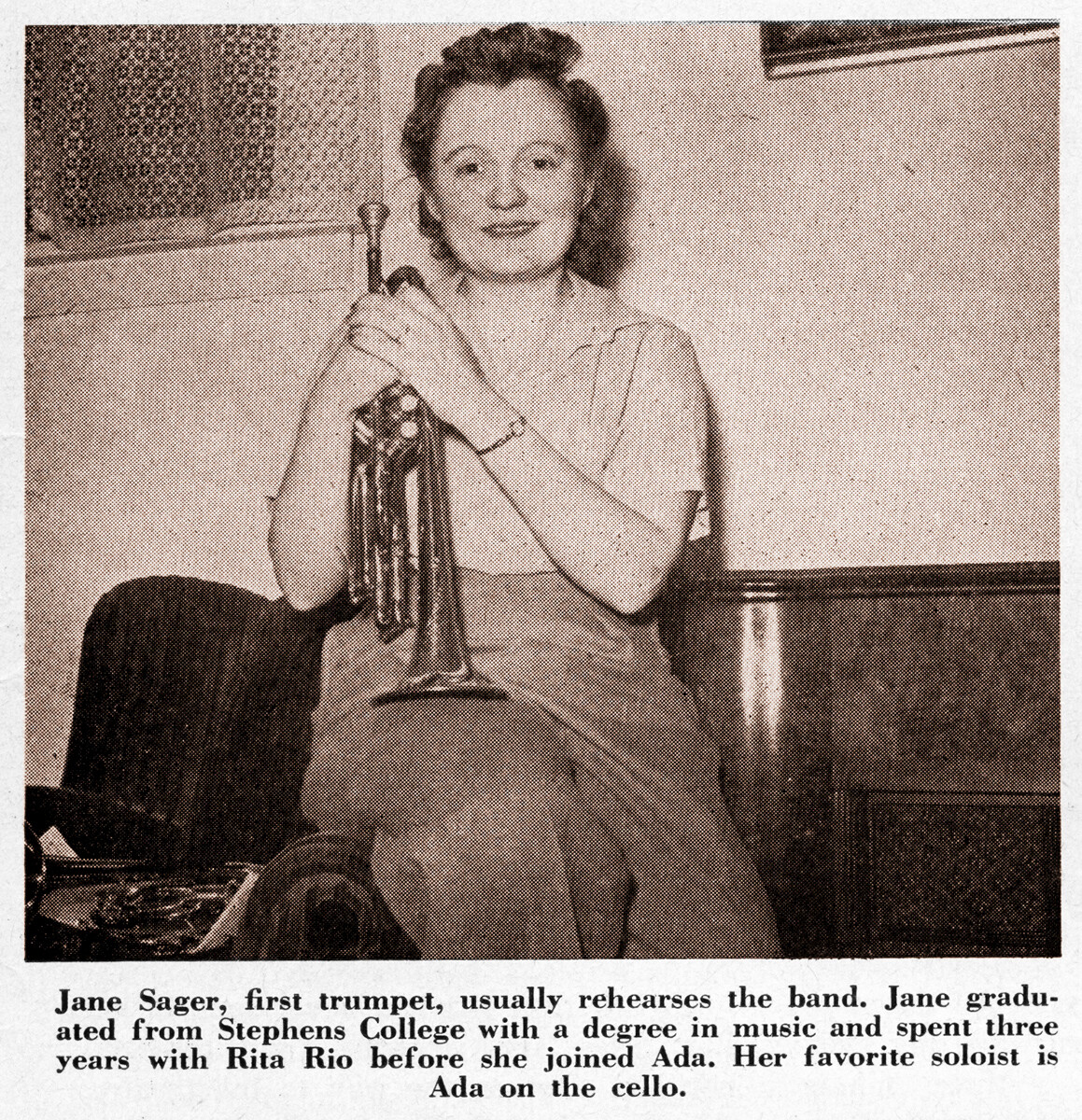

A detailed description of these courageous women and their remarkable ensembles is found in the groundbreaking book by Sherrie Tucker, Swing Shift: “All-Girl” Bands of the 1940s (Duke University, 2000) cited below. The author interviewed Ada Leonard, trumpeter Jane Sager and collected the memories of several musicians from the USO tours.

Working the USO ‘Victory Circuit’

In 1941-42 Ada Leonard and the All-American Girl Orchestra were the first of their kind on the Army-camp “Victory Circuit.” Despite membership in the American Federation of Musicians, they faced adverse conditions, including a 33% pay cut. They were designated Unit #9 of the USO-Show corps which eventually grew to some 800 entertainment units.

Logistical support was inadequate at first, provisions for their lodging and meals were non-existent. The musicians lived, ate and slept on the trains or buses hauling them across the country. Surviving on the “terrible sandwiches” from on-board food concessions, their train coaches were side-tracked in freezing weather for hours making way for higher priority troop transports.

They eluded attempted assaults by rioting sailors, were exploited by unscrupulous booking agents and pressured to play for injured soldiers on their days off. When a stunned nation was closed for business on the evening after Pearl Harbor, they were obliged to perform.

But USO support improved and Leonard signed up for two more stints, managing her 35-member troupe through a total of three 16- or 26-week tours. The first season they were performing back-to-back shows twice-nightly six days a week for hundreds or thousands of troops on USO stages across the United States.

The All-Girl Bands of Rita Rio, 1930s

Several of the musicians, including Leonard, had been affiliated with Rita Rio, the stage name of Eunice Westmorland (1914-1989). The effervescent actress ran all-female orchestras as part of her movie career.

A summation of her vivacious manner and fine example of a lively ‘all-girl’ orchestra from c. 1938 is “Feed the Kitty”. Rio left music behind in the 1940s when her career as movie actress Dona Drake flourished, making 55 films.

Trumpeters Bernice Lobdell, Carol Brown and Jane Sager worked for Rio. Leonard had danced in one of her traveling shows, telling Sherrie Tucker, “I thought to myself, I do all those things she does. I dance. I sing. I talk.” Ada went looking for a band to lead, male or female. An agent hooked her up with a newly formed orchestra of experienced musicians in need of dynamic leadership.

Jane Sager: ‘I Put the Baton in Her Hand’

Jane Sager (1914-2012) was a skilled trumpet and violin player who helped build the ensemble with founder and first saxophonist Bernice Little, telling Sherrie Tucker, “I helped organize this band.”

A Milwaukee native with multiple careers in Swing and Symphony, she had performed in Wisconsin ballrooms and nightclubs from the age of 14, sat-in with Roy Eldridge and toured with One-Arm Miller’s Traveling All-Woman Band in 1935. In the 1950s she was in Ina Rae Hutton’s all-female band on television and taught famed trumpeter Herb Alpert at her Hollywood studio.

Having observed Rita Rio, Sager understood the necessity for a vivacious mistress of ceremonies. Yet, the selection of Leonard as their new leader alarmed Jane and her associates at first. So, they scouted out her burlesque act at the Rialto Theater in Chicago and were favorably impressed: “Ada had ABSOLUTE CLASS – never ‘took off’ a thing and glided with beautiful grace across the stage.”

Having observed Rita Rio, Sager understood the necessity for a vivacious mistress of ceremonies. Yet, the selection of Leonard as their new leader alarmed Jane and her associates at first. So, they scouted out her burlesque act at the Rialto Theater in Chicago and were favorably impressed: “Ada had ABSOLUTE CLASS – never ‘took off’ a thing and glided with beautiful grace across the stage.”

Jane Sager befriended Leonard advocating for her leadership, telling Sherrie Tucker, “I put the baton in her hand.” They worked hard together woodshedding, upgrading her conducting chops. Ada lacked formal training, but that was not unusual among Swing musicians or bandleaders.

During the first season Sager had a rather large role and was, in effect, the music director or “straw boss.” She surreptitiously signaled for Ada the count-off beats for tunes with the tip of her horn. “I couldn’t have done it without Janie,” Leonard confided to Sherrie Tucker.

Deploying the All-American Girl Orchestra

Launching on December 20, 1940, their first lengthy residency was four weeks at Hotel Ohio in Youngstown, OH. Sager described a typical show of ninety-minutes or more.

Their programs opened with a bright instrumental like “Bugle Call Rag.” Then a vocalist, perhaps saxophonist Brownie Slade, would stir up the crowd singing a moving ballad like “White Cliffs of Dover” or “Once in a While.” “One O’clock Jump” and “St. Louis Blues” were in their repertoire, but Leonard kept the hot music limited, saying “People don’t expect girls to play high powered swing all night long. It looks out of place.”

Sager was a featured soloist taking a generous turn in the limelight with her famous rendition of “Trumpet Concerto” by Harry James. Then she asked for requests; picking one, she performed accompanied by only bass and piano. Dancer Mary Sawyer was featured in a number and there would be a comedy act. Leonard sang a torch song leading to the grand finale.

The trumpeter recalled their stodgy red and white striped blouses and deep blue skirts on the first tour. Which were subsequently replaced by more professional costumes ranging from sensible skirts and tailored blouses to bare midriff tops in floral patterns, or frilly “monstrous pink things” in the words of saxophonist Roz Cron. The petite leader’s stage costumes were always “form fitting and slinky” emphasizing her lithe figure.

Under Contract to Uncle Sam

The USO sternly warned entertainers that they were under contract to and representatives of the United States Government. Performers were expected to present only “100% clean shows.” Violation resulted in immediate dismissal, even overseas with transport home.

At domestic Army camps, shows were mounted in conventional recreation halls, movie theaters and such. But outdoors, and especially overseas, improvised stages might be roughly mounted on delivery docks, bare plywood on barrels, or even a truck bed. USO-Show contractors were expected to perform at their very best regardless of conditions, “whether it’s before 10 men or 10,000 men, play as though you were on the stage of Radio City [Music Hall].”

Leonard’s interpersonal encounters reflected the predominant male privilege and blatant sexual harassment of the era. Some commissioned officers for instance, assuming that visiting girl bands were a personal perk, expected social intercourse, dates or sex. Ada and her musicians learned to parry, maneuver and deflect the worst kinds trouble.

Besides the entertainment on offer at USO clubs, enlisted men could write letters, get free coffee and donuts, socialize or receive pastoral guidance. At its peak in 1944-45, the United Service Organization hosted some 3,000 venues worldwide.

America’s Entertainment Corps Musters

The American entertainment industry — music, radio, film, theater and the related crafts — acted early and often supporting the troops. Leonard was soon joined on the USO circuit by the likes of The Andrews Sisters, Jack Teagarden and Duke Ellington. They were followed by a stampede of singers, dancers, comedians, theatrical actors, movie stars and the biggest names in show business: Bing Crosby, Bob Hope, Lucille Ball, Milton Berle, Jack Benny, Harpo Marx and Dinah Shore.

In February 1942, Down Beat magazine reported “USO Bookings Are Underway All Over US.” Orchestras performing in January and February alone included Count Basie (Windsor Locks, CT), Ted Lewis (Camp Grant, IL), Lionel Hampton (Fort Meade, MD), Ray Herbeck (Fort Hancock, NJ) and Benny Goodman in the New York area.

The most difficult and taxing undertaking for the All-American Girl Orchestra was visiting injured soldiers at hospitals. For one thing they were frequently pressured to make these appearances on their days off. And it was emotionally draining.

Sager recalled for Sherrie Tucker a wrenching moment that left a deep impression. While fulfilling a request for Bunny Berigan’s “I Can’t Get Started” from a multiple-amputee she struggled to maintain her composure:

“And he was a stump . . . I’ll never forget those eyes . . . They were the most terrifying eyes, yet, at the same time, so pitiful . . . You can’t blow a horn when you laugh or cry . . . but I’ll never forget those tears were pouring down. My eyes, the tears were running all down my face. It was the most terrible experience . . . It haunts me.”

Ada’s One-Woman Riot

During the first season, Leonard was continually thwarted by USO administration and clashing with commercial bookers and indifferent managers. Her staff were disgruntled about being prevailed upon to sacrifice their free time for hospital gigs. They were being denied days off and time needed for maintaining their clothes, costumes and personal equanimity.

Grievances mounted, relates Sager, until “Ada and all of us were just going crazy.” Leonard finally exploded, kicking a particularly disagreeable business agent in the testicles:

“. . . she kicked him so hard, he turned about five colors. She about near killed him. And then she called him a son of a bitch . . .

She broke every [makeup] light, she broke every mirror. She threw things. She threw their makeup all up against the walls. And then she took her gorgeous gowns and pulled them one after the other off the hangers. . . she went out of her mind. Well, let me tell you, after that, they changed their tune.”

A Free Agent

After the first USO tour, Leonard took the band commercial before resuming the training camp circuit in January 1943. Acting independently on subsequent tours she split their schedule between local theaters, dance halls and the USO.

The orchestra typically played one-nighters at army camps on weekdays, alternating with commercial gigs on the weekends. The orchestra also thrived in a second-tier marketplace of small-time venues known as “Kemp Time,” because most of the jobs were booked by Stan Kemp, the brother of bandleader Hal Kemp. And they performed at increasingly prestigious venues across the nation.

The USO offered the ensemble more than one opportunity to perform overseas. The leader left the decision up to a secret and unanimous vote of her band members. But “I couldn’t get the girls to go to Europe” recalled Leonard. “They were afraid.” USO travel could be hazardous and a few entertainers were injured or killed in airplane crashes overseas. Even though the ensemble sometimes traveled by military aircraft stateside.

Stars of the First Season Roster

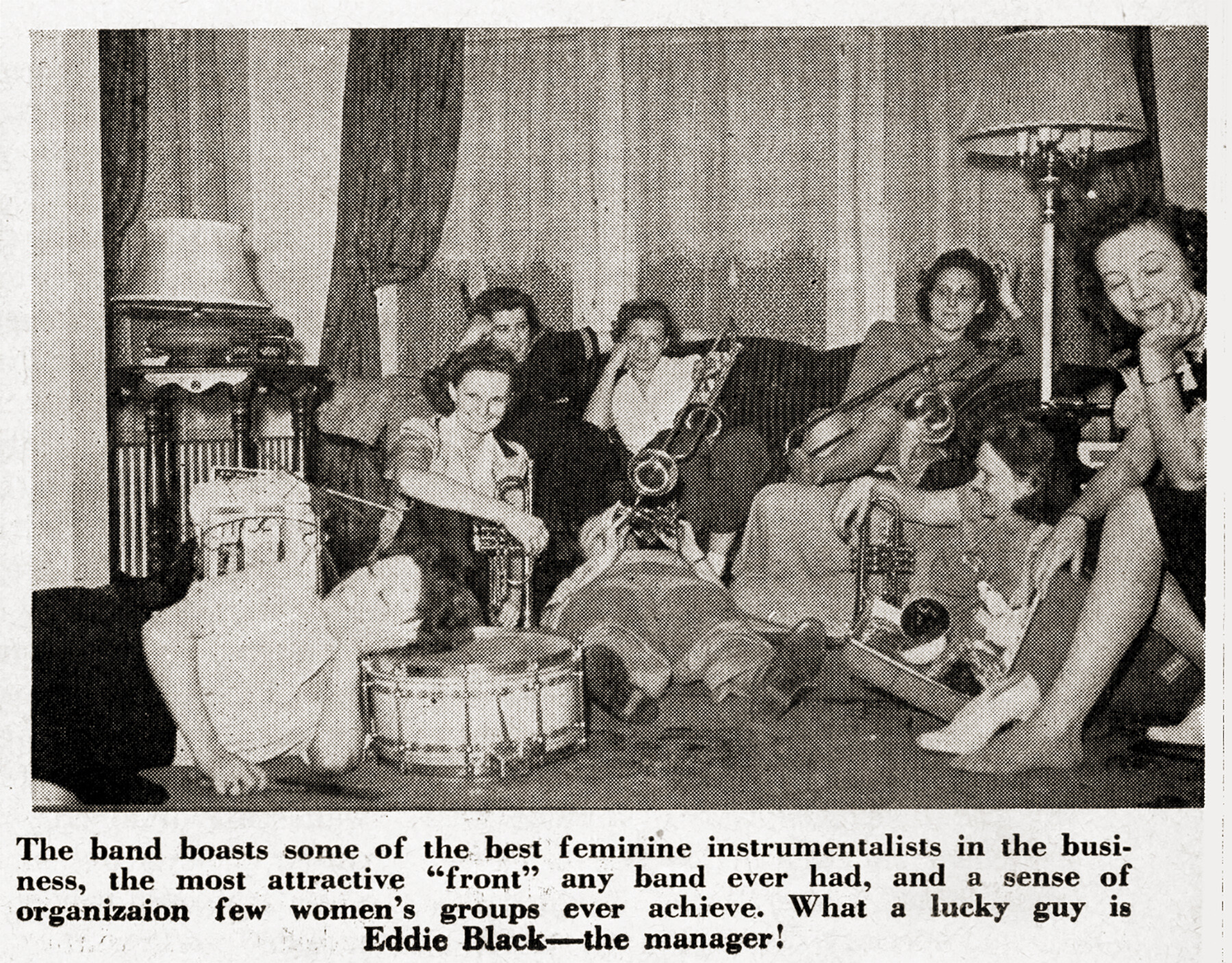

The All-American Girl Orchestra was brimming with accomplished professionals, alumni of Midwestern symphony orchestras and veterans all-women Big Bands. According to a September 1941 magazine profile, eight owned automobiles and the band often drove to gigs. Two were married and the average age was 25.

First saxophonist and founder Bernice Little was a former bandleader and had been in the Chicago Women’s Symphony for nine years. Violinist, Cecilia Toohey was with the Chicago Symphony for seven years and Joan Koupis was “concert mistress” for the University of Minnesota Symphony for four. Musicians often migrated to and from similar groups as with most popular orchestras.

Trumpet player Frances Shirley left to work for the Charlie Barnet orchestra. But she was “completely demoralized” by the cruel hazing from male musicians, driving her back to the Leonard outfit for a season.

Brownie Slade played tenor and alto sax and sang. Jane Sager had studied violin at Stephens College with further tutelage from professionals of the Chicago Symphony, building a multi-faceted career playing both violin and trumpet. Drummer Dez Thompson who took “flashy solos” worked six years with Phil Spitalny’s All-Girl Orchestra.

Boston-born and Jewish, Rosalind “Roz” Cron (1925-2021) had played flute, clarinet and saxophone from the age of nine. Touring with Leonard at age 18, she moved to The International Sweethearts of Rhythm in 1944, playing lead alto sax for three years. Cron joined ‘all-girl’ bands because, “It was my only way to go on the road and perform.”

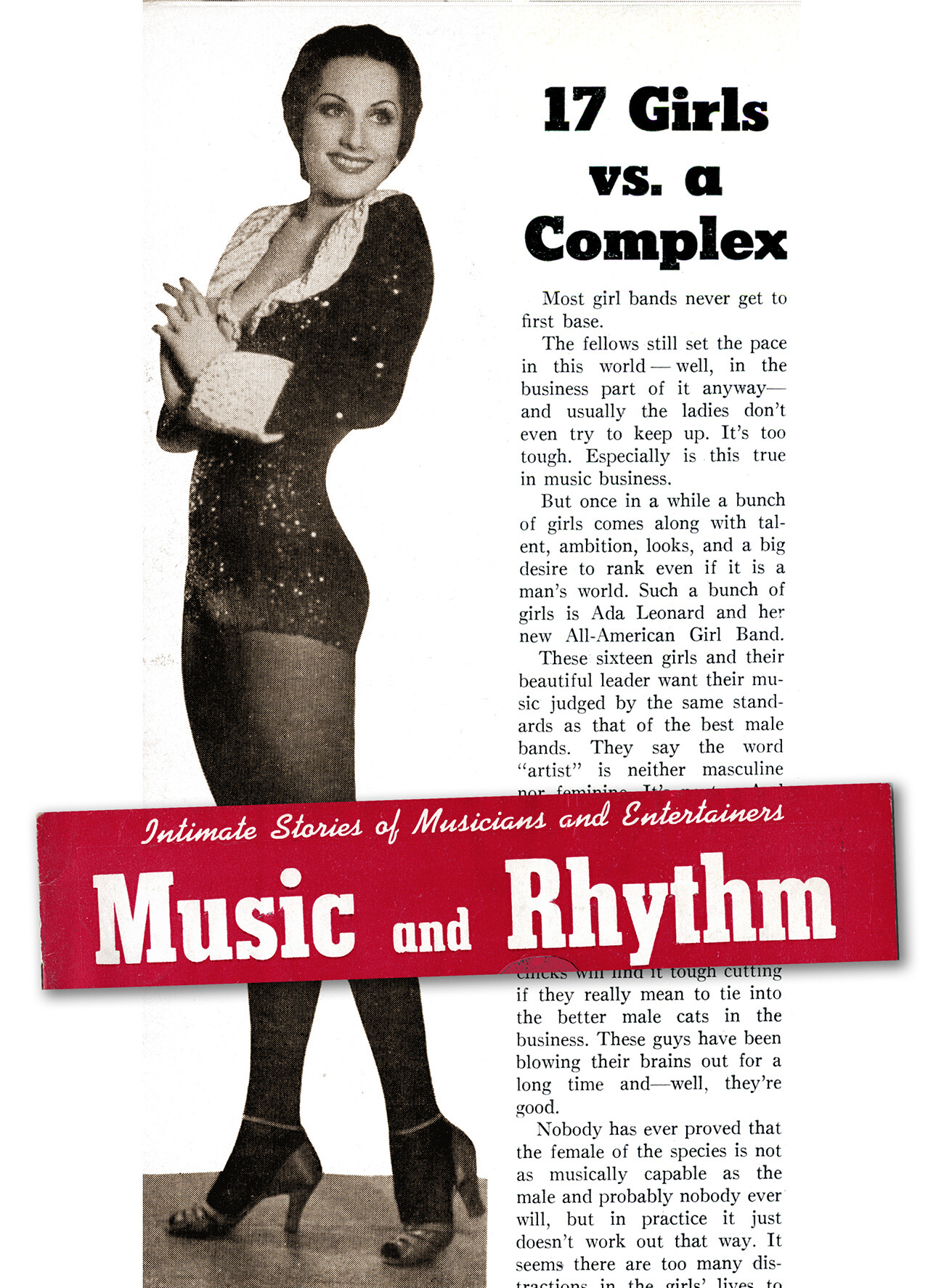

Music and Rhythm Magazine

A popular magazine, Music and Rhythm, featured the All-American Girl Band [sic] in September 1941, offering a two-page spread with ten photos, several reproduced above, three depicting the musicians in baggy pajamas. The editors ignored the available facts, stooping to disrespectful psychobabble instead:

“It seems that there are too many distractions in the girls’ lives to let them stay with music, and really stay, the way a guy does. So, the poor dears are torn in two directions, and they usually settle the problem by throwing away their instruments somewhere between harmony and counterpoint. It’s either that or a lifelong battle with the old maternal complex.”

Such disparagement faded away after Pearl Harbor. But the paternalism, ridicule and hostility resumed once the national emergency had passed and male musicians returned seeking their former jobs and social positions.

A She-roic Tale

This is an uplifting, perhaps even heroic tale of feminine solidarity, camaraderie and empowerment only possible during a brief bubble of opportunity that dissolved at war’s end. Leonard successfully navigated her own course between a military-USO bureaucracy and the commercial marketplace.

Sherrie Tucker compiled excellent research and precious oral histories for Swing Shift making huge contributions to our understanding of these musicians and their motivations. But her narrative line is blurred by preoccupation with how their unconventional cultural, social and gender roles reconciled with pre-feminist America.

Sherrie Tucker compiled excellent research and precious oral histories for Swing Shift making huge contributions to our understanding of these musicians and their motivations. But her narrative line is blurred by preoccupation with how their unconventional cultural, social and gender roles reconciled with pre-feminist America.

Operating a Swing orchestra was a challenging venture in the best of times, an exercise in managed chaos during WWII. Struggling against male prejudice for a decade and a half, Leonard was an effective bandleader who parlayed modest talents and golden opportunities into a meaningful career.

Part two investigates the subsequent travels of the Leonard orchestra, extant into the 1950s. Also profiled is an all-female ensemble that toured overseas for the USO: The Sharon Rogers Band. Part three features the all-female International Sweethearts of Rhythm including their tour of Germany.

Links:

Find more at the Ada Leonard page of the Jazz Rhythm website: www.JAZZHOTBigstep.com

Dynamic Women of Early Jazz and Classic Blues, Pt 1

Dynamic Women of Early Jazz and Classic Blues, Pt 2

Women of Jazz – five radio programs

Books:

Swing Shift: ‘All-Girl’ Bands of the 1940s, Sherrie Tucker, Duke University Press, 2000

The Sharon Rogers Band, Pat McGrath Avery, self-published, 2010

Periodicals:

Music and Rhythm Sept. 1941

Down Beat, 1941, 1942

Metronome, 1943

YANK: The Army Weekly, Sept. 10, 1944

Dave Radlauer is a six-time award-winning radio broadcaster presenting early Jazz since 1982. His vast JAZZ RHYTHM website is a compendium of early jazz history and photos with some 500 hours of exclusive music, broadcasts, interviews and audio rarities.

Radlauer is focused on telling the story of San Francisco Bay Area Revival Jazz. Preserving the memory of local legends, he is compiling, digitizing, interpreting and publishing their personal libraries of music, images, papers and ephemera to be conserved in the Dave Radlauer Jazz Collection at the Stanford University Library archives.