A little-known fact in the Billie Holiday death saga is that jazz singer Adelaide Hall made a personal visit to Billie’s bedside at the Metropolitan Hospital in June 1959, a few weeks before Billie died. What happened that day in Billie’s hospital room has never before been publicly disclosed. However, it was privately documented on at least two occasions; once to the journalist Max Jones during a taped interview Hall gave for a British Library jazz project in 1988,1 the other to the writer and long-time friend of Miss Hall’s, Iain Cameron Williams.2

Although Adelaide could not count herself as a close friend of Billie’s, they did know of one another. Brooklyn-born Adelaide lived in London, so the two singers did not revolve in the same circles. When Billie first toured Europe in 1956, she stopped off in the UK for concerts in Manchester, London, and Nottingham. After receiving such a warm reception from UK audiences and finding the British lifestyle considerably more agreeable than back home, she gave serious thought to resettling there.

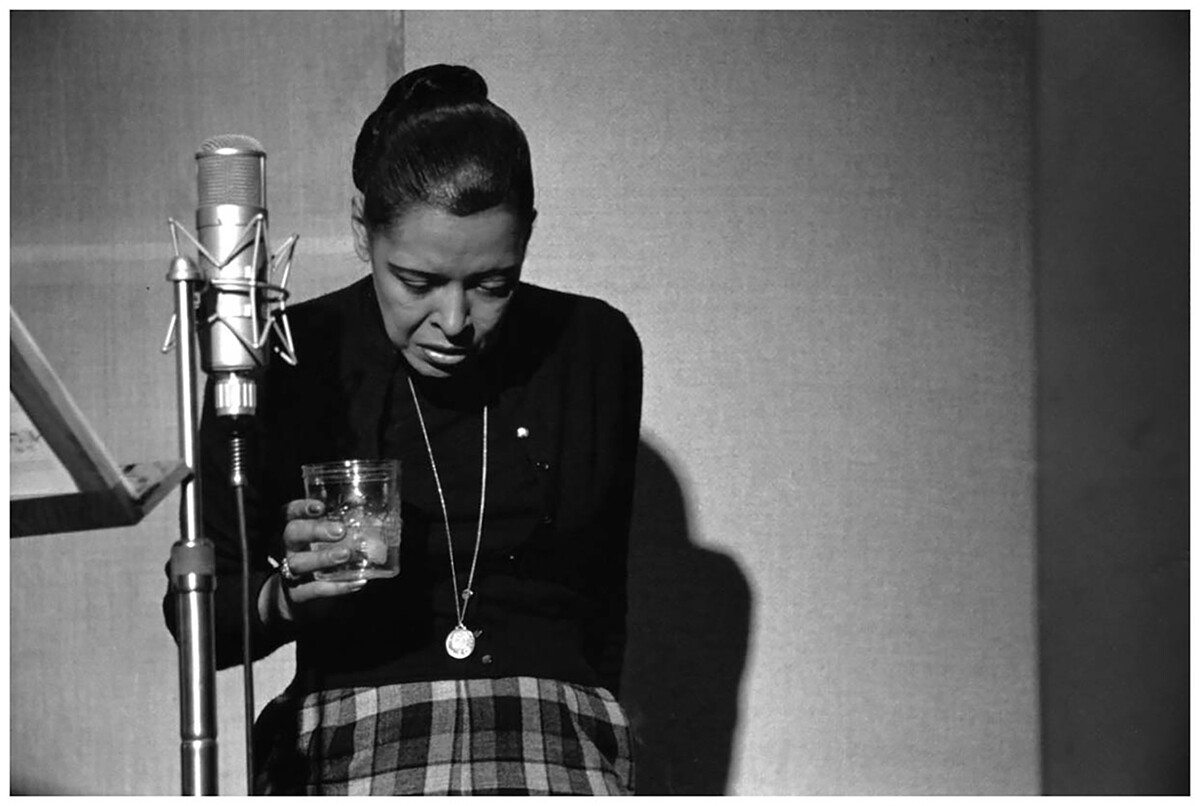

Billie once described her crazy life as trying to live 100 days in one day. “I myself have tried to please so many people. I guess we all suffer.” It was as if she knew she might not be around for too long; both of her parents had died before reaching fifty.

Adelaide had spent the past two years in New York co-starring on Broadway in the hit musical Jamaica. The show opened on October 31, 1957, and ran for 558 performances, giving its last airing on April 11, 1959. Fifteen days later, on Sunday, April 26, Adelaide attended a Spring Cocktail Party thrown in her honor at Wells Restaurant—“Famous Home of Chicken and Waffles”—on 7th Avenue in Harlem. Wells’ owner Joe T. Wells had personally arranged the evening. Adelaide was never one to refuse a dinner invitation, especially if a floorshow was included.

Shortly afterward, Adelaide sailed to London to spend a couple of weeks with her husband, Bert, who had recently been unwell. It could have been that she performed cabaret aboard during the five-day voyage in return for a fee and complimentary passage, one of the perks of being a star. Certainly, Adelaide did, for a period during the 1960s, work on cruise liners as an entertainer. The trip may have been one of her early assignments under that arrangement.

In New York, at 2 p.m. on Sunday, May 31, 1959, Billie collapsed in her small rental apartment at 26 W. 87th Street and fell into a coma. A police ambulance stretchered her to the Knickerbocker Hospital, where she remained unattended for over an hour before a doctor misdiagnosed her as suffering from the effects of alcoholism and narcotics dependency before arranging for her to be transferred to Harlem’s Metropolitan Hospital.

After undergoing a thorough medical examination at the Metropolitan, a different diagnosis emerged; Billie was suffering from liver and heart ailments.

During Adelaide’s return voyage to New York, she heard about Billie’s hospitalization on a radio bulletin. Knowing all too well the effects isolation can have on an artist, Adelaide took it upon herself to telephone the Metropolitan Hospital from the ship to enquire if Billie was well enough to have visitors. She was informed only family or close associates were permitted. When Adelaide passed her name over, the telephonist, realizing who Adelaide was, agreed they could make a special concession for her. However, she was forewarned that Ms. Holiday may be semi-sedated or sleeping when she visits due to the medication she was on. One of the first things Adelaide did when she reached Manhattan was to hail a cab to the Metropolitan Hospital.

The two singers would undoubtedly have had much to talk about. Since 1954, Billie had spoken about settling in the UK, where drug addiction was considered an illness instead of a crime. In February 1959, she made another fleeting visit to London to film three songs for the Granada TV show, Chelsea at Nine.3 Adelaide and her husband Bert lived in London, where they’d become established figures in the entertainment world. They owned a spacious townhouse in Earl’s Court with numerous bedrooms, and Bert had managed various London clubs, including the Calypso in Regent Street. Billie was also good friends with the British music journalist Max Jones and his wife, Betty.4 These were great contacts to have if Billie was serious about living in England.

When Adelaide arrived at the hospital, she was shown up to Billie’s private room, Nº 6A12. No sooner did she step into the room than it became apparent that Billie was semi-sedated, staring blankly at the wall.

“Hello Billie, I don’t know if you remember me,” asked Adelaide while introducing herself, but Billie was unresponsive, “not a smile or anything.” Hence, for the duration of her visit, Adelaide did the talking, at the end of which she promised to return when Billie was in better health and able to receive visitors. Adelaide bade Billie goodbye and left. The following morning, Adelaide heard that two of Billie’s friends visited Billie after Adelaide had left. They brought the “powder” with them. Once they were inside Billie’s room, the two visitors asked the nurse if she could find something out for them, which entailed her leaving the room to source the information. While the nurse was absent, the two visitors administered the “powder” to Billie. When the nurse returned, the two visitors were ready to leave. Shortly after they departed, the nurse noticed specks of white “powder” beneath Billie’s nose on her lip.

Billie was arrested on Friday, June 12, for narcotics possession. The cops confirmed a nurse had uncovered a package of white powder (later proven to be heroin) in Billie’s room. Billie claimed it had been stashed at the bottom of her pocketbook.5 It was widely suspected the drug had been planted. However, the cops weren’t convinced and believed a visitor smuggled it into her room for her to use. They intended to question all her previous visitors. Intriguingly, Adelaide was never contacted or questioned by the police. In 1988, during Adelaide’s interview with Max Jones, Max told Adelaide he knew the name of one of the visitors but did not reveal who it was.

Later, in Billie’s hospital room, while observing all the commotion around her, the singer suddenly remarked to the cops and nurses, “why don’t you all slow down a little.” This was not Billie at her most troubled; those days had passed. This was Billie taking stock of her life. Remarkably, Billie’s health began to rally over the next couple of weeks, then worsened, and on Friday, July 17, at 3:10 a.m., she died, aged 44. Although she had been arrested for drug possession, she had not yet appeared in front of the magistrate. That was scheduled to take place later that morning.

I never mentioned the Billie episode in my biography of Adelaide for two reasons: the period I cover in the book does not go beyond 1939, and I didn’t have additional evidence to back up the story; I only had Adelaide’s one-to-one account. I never heard her talk about it again. Then, in 2021 I came across excerpts of Adelaide’s 1988 interview with Max Jones on the British Library website. In the transcript summary, I noticed that Adelaide mentions the Billie incident to Max. Having since heard the full two-and-a-half-hour interview, I realized I now had the additional verification I was looking for.

With the 63rd anniversary of Billie’s death fast approaching, it seemed an appropriate time for me to knuckle down and chronicle the event.

If Billie’s arrest happened the same day the nurse spotted the “white” specks of powder on Billie’s face, it’s fair to assume that June 12 was probably the day Adelaide visited Billie.

For a time after Billie’s passing, Adelaide returned to wearing a white gardenia in her hair as a tribute to the singer, a fashion she’d previously copied from her several years earlier. Adelaide never released any information to the media about her visit to see Billie; she felt it was too personal and did not want to see Billie’s name further sullied. I always felt Adelaide confided the story in me because she wanted it to be documented for posterity, but, as has come about, not until after she too had passed away. Adelaide Hall and Max Jones both died in 1993.

Text © Copyright Iain Cameron Williams, 2022.

1 Adelaide Hall and Max Jones transcript, part 2 (tape 2), British Library, 96 Euston Road, London, NW12DB.

2 During interviews conducted by Williams with Adelaide for the biography Underneath a Harlem Moon.

3 Billie filmed her segment for Chelsea at Nine at the Chelsea Palace theater in London.

4 The Max Jones Archive: www.maxjonesarchive.uk

5 United Press International (UPI), 13 Jun 1959.

Iain Cameron Williams was born in Sheffield, Yorkshire, of Scottish and Welsh ancestry. His mother was born in New York and his father was born in Kalimpong, West Bengal, India. Iain Cameron Williams is the writer of The KAHNS of Fifth Avenue (2022), The Empirical Observations of Algernon (2019), and Underneath a Harlem Moon: The Harlem to Paris Years of Adelaide Hall (2003). The KAHNS of Fifth Avenue by Iain Cameron Williams (ISBN-13: 978-1916146587) is available to purchase via Amazon and all good bookstores or via the website www.thekahnsoffifthavenue.com.