A Conversation with Michael Feinstein on the Enduring Appeal of Popular Music

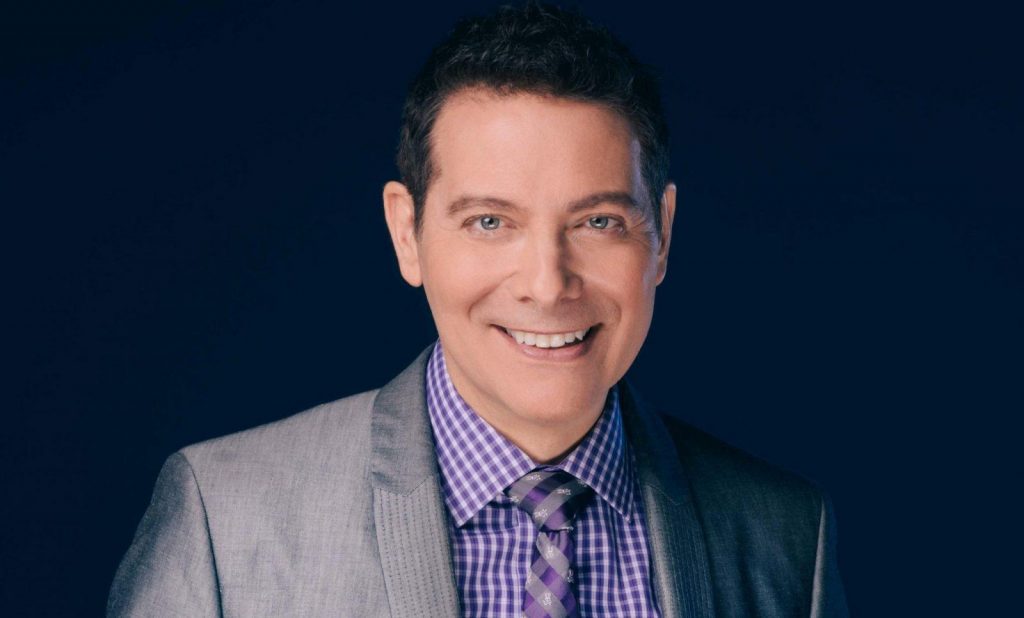

For aficionados of the Great American Songbook, Michael Feinstein needs no introduction. The man wears many hats—pianist, singer, arranger, songwriter, author, conductor, educator, nightclub owner, archivist, and historian all with an eye on presenting and preserving popular music from the first half of the 20th Century. His talent and passion have earned him a global following and scores of accolades including multiple Grammy and Emmy nominations. Feinstein also possesses arguably the greatest private collection of sheet music and music memorabilia in the world. He has donated the collection to Center for Performing Arts in Carmel, Indiana, for the establishment of the Michael Feinstein Foundation for the Preservation of the Great American Songbook. The center’s president told The New York Times in 2011 that the collection “could fill a 70,000 square foot building.”

Feinstein spoke with The Syncopated Times from San Francisco, where he owns the nightclub “Feinstein’s at the Nikko” in the Nikko Hotel.

TST: When you were growing up in Columbus, Ohio during the 1950s, why did the music of decades earlier resonate with you? You have said your parents played a lot of music but what made you want to spend your life wanting to play it and preserve it?

Michael Feinstein: To answer “why” is very difficult. Music causes an emotional response in a human, and in my case when I was very young, the music that most appealed to me was older music. It is music that was mainly on the old 78 rpm records, and when I started playing the piano, music that I found on old sheet music. There was something about the harmony, the orchestrations, the way that the music was constructed that was more appealing to my soul—and my heart—than the contemporary music, which simply did not have the same emotional resonance. It simply didn’t interest me. So, I simply followed and continued to listen to and play the music that appealed to me.

TST: That connection led you to Los Angeles at the age of 20 in 1977. You wanted to perform but found a job as archivist, researcher, and friend to the legendary Ira Gershwin. How did that experience change you and what did you learn from him?

MF: Meeting Ira was certainly a watershed experience in my life. I never felt that I would meet any of the creators of the songs that appealed to me as a kid. He was 80 years old, and the experience was one that was truly life-changing, because he taught me so many things that I could not have learned in any other way—not only about interpreting the songs, and very specific information about the songs, but also introducing me to his contemporaries and having the access to his materials. He was a very kind man. He never had children, so I was like the grandson that he never had. It was all very extraordinary and heavy, especially at the age 20, which is an important age in anyone’s life, because we are forming ourselves in many ways. And so, he transformed my life incalculably.

TST: The love of the Gershwins’ music, and access to Ira’s personal collection, led you to write the beautiful and heartfelt best-selling coffee-table book The Gershwins & Me: A Personal History in Twelve Songs (Simon & Shuster, 2012). Did you write it because you wanted to ensure that future generations would have an accurate account of their life and work?

MF: I don’t really think in terms of future generations for myself. I did want to preserve what I could with my experiences with Ira and what I learned from him, and what I knew about the Gershwins. Even though I am involved with high school kids through the foundation I created to pass on the music, I am pretty much focused on “right now.”

TST: Tell us about the mission of the Feinstein Foundation and what kind of work are you doing there with young people?

MF: About 10 years ago I created the Great American Songbook Foundation, and the purpose of that organization, first of all, was to preserve the artifacts that I have collected through the years in the way of memorabilia, sheet music, recordings, and other materials related to American popular music. In addition, I wanted to find a way to pass this music on to other generations. And so, we started an annual high school Songbook Academy that exists for the purpose of teaching young people interested about interpreting these songs and actualizing it in their lives. We have this annual event where 40 kids are picked from all over the United States, from all 50 states, who come to Indiana for a week and experience this Songbook Intensive, which is life-changing and wonderful in the way that they are mentored and learn how to connect with their souls in a deeper way.

TST: What do they learn from the music?

MF: Through the music, they learn things about the ability to express emotions and connecting deeper with who they are and connecting also with other people their age who are on a similar path. By the end of the week, we have an event at our theater, the Palladium, that is open to the public and sells out, that is like our personal American Idol, only kinder and gentler and generally with better music [Feinstein laughs].

TST: Young people are always using online services like Spotify and Apple Music that gives them access to almost every piece of music ever recorded. Before that, you have to have a record or compact disc to listen to music and now it is all in their pockets. Do you think that kind of access is helping to keep this music alive?

MF: It’s remarkable because when I was younger, it took me sometimes years to find some of the things I was looking for. When I was trying to find a recording of the Gershwin second rhapsody, when I was in high school, there were no recordings of that piece in print. There were no recordings available, so one had to find it through used record stores. We’d have to write letters and make long-distance calls to places all over. And I eventually found the Oscar Levant recording, and many years later I stumbled upon the Leonard Pennario recording of the Gershwin second rhapsody (Capitol Records, 1952) which was the only recording in stereo. Now it really is at the touch of the fingertip, but like anything you have to be led there, you have to know about it.

TST: In your work as an archivist, are there any songs or songwriters from the first half of the 20th century that have maybe been unfairly overlooked, or should be better remembered today?

MF: Many! There are many great songwriters who are unacknowledged. I mean, Johnny Green [1908-1989], who was a marvelous songwriter, he only had like a half a dozen hits. They were big hits, especially “Body and Soul,” “I Cover the Waterfront,” “You’re Mine You,” but he was an incredible songwriter and wrote other songs that were great. [Another is] Burton Lane, [composer, 1912-1997] who was known for Finian’s Rainbow and On a Clear Day You Can See Forever. Burton only wrote four book shows for Broadway, and he was not prolific, but he was extraordinarily gifted. [Feinstein recorded two tribute albums in 1990 and 1992: Michael Feinstein Sings the Burton Lane Songbook, Vol. 1 & Michael Feinstein Sings the Burton Lane Songbook, Vol 2; both recordings feature Lane on piano.]

TST: Anyone else come to mind?

MF: Willard Robison [composer, vocalist, 1894-1968], who was sort of like the country version of Gershwin. He deserves to be better known. There were just so many prolific and great writers. Dana Suesse [musician, 1909-1987] was incredibly gifted [as was] Louis Alter [songwriter, 1902-1980]. I mean, we’re talking [about] a time in American music when it was so rich with creation that it is truly an unmined vein of gold. And then there are all the concert works, the people who were trying to emulate Gershwin. When Paul Whiteman had these annual concerts, his continuing experiments in modern music, where all these other composers and creators were writing orchestra pieces that were a bridge between American popular songs and concert music. There’s a lot. And I don’t know that we’ll ever get to all of it.

TST: In an episode of your PBS series Michael Feinstein’s American Songbook, you talked about how you won’t have enough time in your life to listen to all of the music you’ve collected. But that hasn’t stopped you from adding to your immense collection.

MF: That is true. It’s incredible what’s out there, especially with sound recordings where there are radio broadcasts, production discs, home recordings, and studio discs, and all kinds of other things that are hard to put your hands on, and there’s millions of them. It gets into millions of items. It’s dizzying, and all these things that repose in libraries and other repositories. Some of them are obscure, [and] people don’t even know that they are there. They’re also aren’t people that know how to play them or preserve them. It’s a big issue.

TST: What do you think of the state of the music today? There are many younger artists who are out there not only playing the music but living it. Do you think this is going to perpetuate it?

MF: I think that it’s always the grassroots effort and everything that one does, plants little seeds, it’s exposing people to the music. I think that especially young people, who are more open-minded than their elders who may have become set in their ways, once they are exposed to it, it’s a fait accompli. It doesn’t replace other music choices, but it becomes another avenue of musical expression that has meaning.

TST: You’ve been critical about some of these pop performers who have latched onto the Great American Songbook. We don’t have to name names here, but you’ve been quite vocal in that. Do you think it takes a certain type of performer to relate and understand and present these songs in the matter of which the creators hoped that they would be performed?

MF: It’s very simple, really. The songs are about the lyrics. And if they’re not given interpretations that are really connected to the lyrics, and if one doesn’t follow an assemblance of what the writers wrote musically, then it becomes something that is like a faint copy of the Mona Lisa. There are many pop artists who have made recordings of these standards because they have an arrogance about it. They think “Oh, I can do that” and they just sing them superficially, not understanding that it comes with the fine-tuning and the depth of interpretation. Just as a number of opera singers have sung standards, and they sing them technically perfectly, but they are bloodless. It’s just about the interpretation. However, in the case of somebody like Rod Stewart, whose recordings bore me to tears, he’s sold millions of recordings, and hopefully they’ll lead other people to those interpretations.

TST: You have not been shy about being critical of Stewart’s Songbook series of recordings.

MF: The thing that people don’t know about Rod Stewart—and his manager told me this—is that when you listen to his first album of standards, for example his recording of “You Go to My Head,” he is literally doing a vocal impression of Billie Holiday. [Feinstein sings in an imitation of Billie Holiday— you go to my he-ad…] I’m not kidding. Play them back to back. You’ll hear that he’s doing Billie Holiday! That was his frame of reference, [and] that’s what he’s doing. So—you know—he likes Billie Holiday—so that’s a plus [Feinstein laughs].

TST: Your new show for this year, Shaken & Stirred: Reimaging Songs features singer Storm Large, who’s sung with “Pink Martini.” Please tell us about her.

MF: Storm has had a formidable career and extraordinary life. She wrote a very beautifully written autobiography a few years ago about her very unique existence up to this point. And she is an incredibly gifted singer whom I first heard in Australia when she was doing an autobiographical show. And she’s mainly a rock ’n’ roll singer but can sing other things. Storm is the kind of performer with whom I love to collaborate, because she not only is incredibly eclectic musically, but stretches me as an artist.

TST: And what’s the focus of the show?

MF: The show will present a lot of standards, but also will have different kinds of interpretations of the standards. Because you take someone like Louis Prima, who in the ’40s and ’50s took standards and re-interpreted them for his band, and then for his small group. The fun new ways to do the songs. So, I like the idea of expanding the Songbook and doing the songs in ways that will appeal to the different styles that have been done by different generations. And that’s the way that these songs are still alive.

TST: You are debuting the show at the Chautauqua Institution, a place that has a special connection to music.

MF: It’s a very special, wonderful place for music, and it will be a great honor to be there again.

George Gershwin spent time at Chautauqua in 1925. [NOTE: Gershwin finished his “Concerto in F” in Chautauqua Institution’s music practice rooms.] It’s that connection that always delights me because I always imagine him there. I’m treading the same paths that he did. And I believe that energy and ghosts leave their mark there, and that energy remains, so it adds a little bit of excitement to the experience for me.

TST: For a show like Shaken & Stirred, how much time goes into making sure that you have the right songs chosen and the right arrangements?

MF: A lot of time. It’s also an evolution, because things happen extemporaneously on stage. It’s one of the fun things. Live performing is not only an evolution, but it’s interactive with the audience. And the audience interaction is important for me and for Storm because we both play off the audience. And you learn from the live experience the things that you cannot learn in a vacuum without the audience.

TST: And the audiences learn from you in your live performances. You explain the history of the songs and their composers and writers. Is that still part of your new show?

MF: That’s always an important part of the marginalia, the anecdotes, the stories, and the jokes, the funny things that relate to the songs. The humor is a very important part of the shows. Number one, these shows always have to be entertaining, but I’ve always slipped in the educational stuff. The people, hopefully, never know it, because it is about having fun, and it’s about enriching people’s lives through the gift of music.

For tickets, as well as for Michael Feinstein’s complete tour schedule and other information, please visit www.michaelfeinstein.com.

Brian R. Sheridan, MA, is the chair of the Communication Department at Mercyhurst University in Erie, PA (hometown of Ish Kabibble) and a longtime journalist in broadcast and print. He also co-authored the book America in the Thirties published by Syracuse University Press. Sheridan can be reached at bsheridan@mercyhurst.edu. Find him on Twitter @briansheridan and Instagram at brianrsheridan.