These days we often take performers who sing and play piano for granted, but in the acoustic phonograph world things were a little different. Long before there was Jerry Lee Lewis and Fats Waller, there was Silas Leachman. Leachman was an itinerant musician and singer who came from Louisville with talent the phonograph world had not yet seen. His records are often very valuable to collectors today as he made relatively few and the quality of each was and still remains exceptional for their age.

In the earliest days of the phonograph, accompanists had a hard job. Before the technology had improved just enough to make many copies of records, the accompanists had to play dozens of takes of the same song, but they were just accompanists (most often pianists). Singers and instrumentalists were almost always separate from the pianists, but occasionally the crude recording methods meant that the performers had to do their own. Only in extreme circumstances did this occur, but this is where Leachman fits in.

Leachman was known for his “one man show” records. After spending much of his early life in Kentucky and the Ohio river valley, he settled in Chicago around 1890. He was an amateur minstrel singer and pianist, yet his talents were quickly noticed by others outside of the cheap vaudeville circuit. By 1892, he was making records for the North American phonograph company. He relished making records, so much so that he made sure to spend time perfecting the art of making recordings, and making sure his own accompaniment was appropriately balanced. In 1895, the Chicago Tribune wrote a long piece on him, where his process was described in exceptional detail. This is what was said:

He plays his own accompaniment on the piano and takes care of the machines. He prepares three “records,” as the wax cylinders are called, at one time.

To do this three phonographs are placed near the piano, with the horns at one side pointing away from the keyboard at an angle of forty-five degrees. The horns have to be placed very carefully, for a fifth of an inch makes a great difference in the tone the cylinders will reproduce. When the horns have been adjusted exactly right, Mr. Leachman seats himself at the piano, and, turning his head away over his right shoulder, begins to sing as loud as he can, and that is pretty loud, for he is a man of powerful physique, and has been practicing loud singing for four years. He has been doing this work until his throat has become calloused so that he no longer becomes exhausted after singing for a short time.

The article also states that he made hundreds of thousands of recordings, but this number is likely greatly exaggerated.

As soon as he has finished one song, he slips off the wax cylinders, puts on three fresh ones without leaving his seat, and goes right on singing until a passing train compels him to stop for a short time. In the four years he has been in the business he has made nearly 250,000 records. So great is the demand for them that he cannot fill his orders. It is such exceedingly hard work that he cannot sing more than four hours a day. He gets thirty-five cents for every cylinder that he prepares. He has a repertoire of four hundred and twenty pieces, and his work is put on the market under a score of names. He has a remarkable memory, and, after once hearing a song, cannot only repeat the words and music correctly, but can imitate excellently the voice and expression of the singer.

While he did almost certainly make thousands of recordings, few of these brown wax records survive. The mere mention that he could perform any song after hearing it just once is remarkable, and suggests that he learned his music by ear. Considering his talents, this alone could come as the most impressive. Not only had he an exceptional memory, he also possessed some of the most accurate pitch of any singer who recorded for the phonograph at the time. His pitch and vocal range were even praised at the time, as it was reported in The Phonoscope in 1898 that he mastered the technology so well that he could make a quartette record with only his voice:

Leachman, the twenty-fourth ward politician, is the fortunate possessor of such a voice, and he has made a number of quartet records in Chicago. The singer puts on the cylinder first whichever part it is easiest for him to sing. In putting it on only the one horn and recorder are in place. After he has put the one part on, the reproducing instrument is put on the part. The singer listens and as he hears his voice begin on the part recorded he chimes in, singing a second part in the quartet. Then he listens to both of these parts and joins in with a third part in the quartet. Lastly he listens to the three parts and sings the fourth. The quartet is then complete and four reproducers can be put upon the cylinder and the listener will hear a quartet, which has been made by only one voice.

Even comprehending the amount of experimentation it took to achieve this is dumbfounding. And this is only about his cylinder records, which are so rare, collectors can spend decades never seeing one in person. Owning one is better than gold.

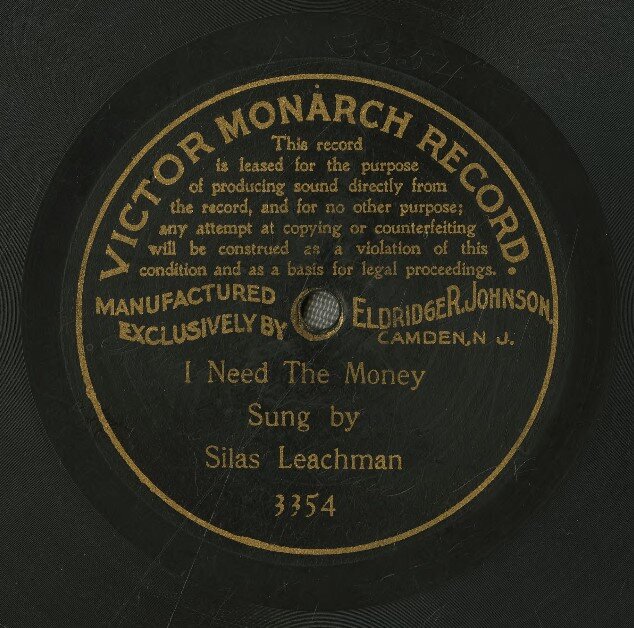

Leachman was asked by the Victor company to make records for them in 1901. It seems that before he went there the first time, he practiced his piano accompaniments, and made sure he understood how his voice could be appropriately recorded with them for the discs. On his first Victor session, he played his own accompaniment, keeping with what he was known for in the phonograph world.

Everyone knew he was unbelievably gifted, but record manufacturers weren’t lining up to contract him. Columbia manager Victor Emerson had some choice words for Leachman’s talents, stating much to the likeness that his accompaniments were a mess of music compared to his “decent” voice, Columbia was likely jealous that their enemy Victor got him first. It is also likely that hiring an accompanist and engineer for him was difficult, as he was used to running the operation all on his own.

Not all of his Victor records feature his own accompaniment, but his most exceptional records do. His accompaniment is fascinating to study, as he was almost certainly musically illiterate, and possessed truly natural talent, fostered in the rural areas of Kentucky. His style was not much different from that of composer Ben Harney and other studio accompanist Fred Hylands. He was a generation older than them however, so in some ways it was more primitive.

Though Leachman is generally underrated in history nowadays, those who are aware of his records and accompaniments cherish the valuable mark he left on recording that was only to return in future decades.

R. S. Baker has appeared at several Ragtime festivals as a pianist and lecturer. Her particular interest lies in the brown wax cylinder era of the recording industry, and in the study of the earliest studio pianists, such as Fred Hylands, Frank P. Banta, and Frederick W. Hager.