Set forth below is the thirty-third “Texas Shout” column, the conclusion of a two-part essay that first appeared in the September and October 1992 issues of the West Coast Rag (now The Syncopated Times). Read part one HERE. The following introduction was added when the column was reprinted in March and April of 1999:

Set forth below is the thirty-third “Texas Shout” column, the conclusion of a two-part essay that first appeared in the September and October 1992 issues of the West Coast Rag (now The Syncopated Times). Read part one HERE. The following introduction was added when the column was reprinted in March and April of 1999:

“The text has not been updated. However, I should note that, since October 1992, a few combos have been formed which feature the jazz style discussed therein, in large part via re-creations of Original Dixieland Jazz Band performances. Also, seeing no point in reprinting detailed comments on a recording issued in 1992, I have tacitly trimmed the record review that closes the article.”

I believe that white New Orleans Dixieland jazz is generally misunderstood, too often judged by the wrong criteria. In my view, you can see white New Orleans players and bands in proper perspective more easily if you remember that they are working within a distinctive Dixieland style, one that maintains an upbeat mood and does not have significant blues content or other emotions. If you do so, you are less likely to criticize its musicians for failing to do something that they are not trying to do in the first place, and you are more likely to judge the music for its strengths, which are considerable.

It helps that process if you step back a pace or two and remember what jazz is all about. As I discussed in “Texas Shout” in November and December of 1991, I believe the distinguishing characteristic of jazz, the one thing that sets it apart from other musics, is its feeling of compelling and passionate forward momentum, often referred to as “hot and swinging”. [See: Texas Shout #23 Dixieland vs. Ragtime Part 1, Texas Shout #24 Dixieland vs. Ragtime Part 2]

Note that this distinction has nothing to do with emotional range or with improvisation. Although I have often seen it said that jazz goes hand in hand with blues content and with improvisation, I personally believe that neither characteristic is essential to a jazz performance and that neither characteristic is unique to jazz.

I don’t want to beat this subject to death again in today’s column, but with respect to emotional range, you can find the complete range of emotion in many types of non-jazz music, such as grand opera, ordinary American popular music of 1900-1950, country, folk, and ragtime. You don’t need to go to jazz to hear music that is blue, happy, nostalgic, humorous, wistful or any other emotion you wish to choose.

Similarly, improvisation – the extemporaneous rendition of musical passages during a performance – is a regular, accepted part of many non-jazz musics, e.g., blues & gospel, country & western, rock ‘n roll, ethnic (the raga music of India, among others), folk and, yes, even ragtime (notwithstanding the opinion of some ragtimers that the only worthwhile ragtime is composed in advance and executed as written). Improvisation, in and of itself, doesn’t constitute “jazzing up” a piece of music nor is improvisation essential to jazz. It’s not too difficult, for example, to find hot dance jazz rides from the twenties, swing from the thirties, progressive or bop from the forties, that contain no improvisation whatever and are as hot and swinging as any jazz fan could want.

The quality that sets jazz apart from other music is that its players articulate the notes, whether blue notes or non-blue, written or improvised, in a way that is hot and swinging. One could conclude from that statement that the hotter and swingier a jazz performance is, the jazzier it is.

Said another way, a hot swinging jazz performance which displays only one emotion is jazzier, more worthy of a higher ranking on the jazz scale of artistic merit, than a slightly less hot, slightly less swinging performance which contains a wide range of blues and other emotions. That is the conclusion I’ve reached after much thought on the subject, but I will warn you that the majority of jazz criticism I’ve seen does not agree with me.

I believe most critics would say that, at least to some degree, a jazzman may (and should, if the goal can’t be attained any other way) cut back on swing and heat in order to achieve a broad range of emotional expression. Doing so may well produce a satisfying overall result. I might even prefer to listen to it under some circumstances. However, in my opinion, a jazzman who follows that approach winds up with a product that may be more well-rounded but is also less jazzy.

At any rate, if you adopt my view of the matter, the work of the white New Orleans Dixielanders gets a new lease on life. If you’re looking for flat-out heat and drive, I’ll match the blistering 1/27/27 Columbia version of “After You’ve Gone” by the Charleston Chasers with just about anything you want to name. For sheer effortless straight-ahead steadily building momentum, Albert Brunies’ incredible Halfway House Orchestra was the equal of any group that recorded in the twenties.

If you don’t knock musicians for failing to play blues, you’re much more likely to be able to appreciate the talents of Red Nichols, one of the most technically gifted cornetists who ever played our music. He had a big round brassy tone, an authoritative attack, the ability to hit pitch dead center across the full range of his instrument and a flexibility which enabled him to execute acrobatics on his horn that would eviscerate most cornetists. Moreover, Nichols’ exceptional skills stayed with him throughout a long and productive career, his latter-day Five Pennies unit being one of the best Dixieland bands of its day, its 1958 Marineland concert on Capitol ranking as a classic of the revival period.

[The following recording is likely from that concert.]

There are those who seem to feel that, by praising someone, you are somehow denigrating or downgrading someone else. Let me say, then, that by trying to raise your consciousness towards the merits of the white New Orleans Dixielanders, I am most emphatically not saying that their accomplishments in any way diminish the work of such immortals as Oliver, Morton, Dodds, Armstrong, Teagarden, Hines and all the others on your list and mine of all-time greats of our music.

I am saying, however, that the white New Orleans material remains thoroughly satisfying when heard today, that some of it deserves to rank alongside the best Dixieland jazz ever waxed, that it should be regarded as part of a distinctive and valid Dixieland style having objectives and standards somewhat different than those of the Black New Orleans musicians, and that its musicians should be judged according to how well they met their objectives and standards. And, I submit, if their music is viewed in that light, it deserves a place on our stages and in the record bins that is larger than the zero it gets now.

Fine, you say, I’m sold, Tex. Now where can I hear some of this great music?

Well, that’s a tough question. As I’ve said, the records haven’t been easy to come by. However, now that the CD era is upon us, I seem to be seeing more archival CD sets that present complete recordings of given artists or bands. Perhaps we’re due for some reissues of the New Orleans white bands of the twenties, Phil Napoleon, Red Nichols, Miff Mole, etc.

[Ed. Note: The Jazz Oracle label has released three 3-CD sets, BDW 8062, 3 & 4 — 9 CDs in all — containing everything Red Nichols ever recorded for Brunswick, including all of the alternative tracks, over 200 sides total.]

European labels have been quicker to recognize the values of the white New Orleans style. Most of the recordings I own of white New Orleans are imports obtained directly from England or through domestic specialty dealers.

It takes a bit of digging to find the right stores or dealers, but if you keep your eyes open reading the Dixieland press, you’ll run across some. I subscribe to a couple of British jazz magazines, keeping a want list culled from records covered in the reviews or ads – sooner or later I’ll discover the albums on a dealer’s flyer or in the rack of some big-city specialty store.

Where can you hear the white New Orleans style at a festival? Beats me. Because the records haven’t been around, today’s bands have had no chance to pick up any significant influence from the white New Orleans musicians. As a result, you can discern only occasional flashes of the style in a musician here and there or in portions of the music of a band that mostly plays some other style.

For example, I hear some white New Orleans surface from time to time when listening to the Hot Frogs, a band that plays a variety of Dixieland from funky New Orleans-ish four-beat to good-natured West Coast revival. The presence is doubtlessly attributable to trumpeter Mike Silverman’s acknowledged appreciation of Red Nichols.

Some of the early Buck Creek recordings contained an element of white New Orleans. This was surely a coincidence because, to my knowledge (and I’ve played a number of gigs with the band), none of the Buck Creekers pays much (if any) attention to the early white New Orleans style bands. At any rate, that flavor isn’t as strong as it used to be, Buck Creek apparently having elected to move closer to Black New Orleans as filtered through the influence of the New Black Eagles.

However, this column was inspired by the arrival on my doorstep of a review copy of the debut recording of the Jazz Salvation Company. As I listened through, I realized that, in spirit and general approach, the Salvations could well have handled the gig at the Halfway House on Albert Brunies’ night off.

I decided to talk about it here as a way of telling you about a style that I personally enjoy very much. (I’ve already told you in these pages that my Halfway House album is my desert island record.) I’d like to alert you to the fact that the white New Orleans musicians did have their own way of playing Dixieland, a worthwhile way which is not, as some writers seem to believe, some kind of flawed imitation of the Black New Orleans approach.

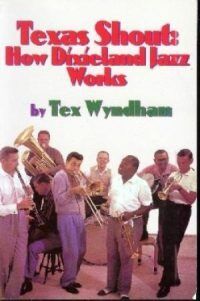

The full run of “Texas Shout” has been collected into a lavishly illustrated trade paperback entitled Texas Shout: How Dixieland Jazz Works. This book is available @ $20.00 plus $2.95 shipping from Tex Wyndham, On request, Tex will autograph the book and add a personalized note (be sure to tell him to whom the note should be addressed).

Tex Wyndham’s 3 CD Guide to Dixieland with music and commentary is available for $20 plus $2.95 shipping. The separate CD, A History of Ragtime: Tex Wyndham Live At Santa Rosa, is available for $13.00 plus $2.00 shipping. On request, Tex will autograph the inner sleeve and add a personalized note (be sure to tell him to whom the note should be addressed).

Send payment to Tex Wyndham, P.O. Box 831, Mendenhall, PA 19357, Phone (610) 388-6330.

Note: All links, pictures, videos or graphics accompanying the Shouts were added at the discretion of the Syncopated Times editorial staff. They did not accompany the original columns and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of Tex Wyndham.

From roughly 1970-2010, Tex Wyndham was: (1) one of the best-known revivalist Dixieland jazz musicians in the US, as cornetist, pianist and bandleader, (2) one of the best-known ragtime pianists in the US, and (3) one of the most respected critics in the US of Dixieland jazz, ragtime, and related music. He is the only person about whom all three of those statements can be made.