While mourning the loss of leader Tony Pringle, the band plays on

Cornetist Tony Pringle always told his bandmates in the New Black Eagle Jazz Band that if he ever stopped playing—for whatever reason—he expected the group to forge on without him. The British-born horn player died May 3 in Massachusetts. He was 81 years old. And, just as Pringle wished, the New Black Eagles intend to carry on.

“Tony had expressed numerous times that he would want the band to keep going if he ever stopped playing,” wrote clarinetist Billy Novick shortly after Pringle passed. “He also believed that we should continue to perform the soulful and uncompromising style of New Orleans jazz that he helped create. We fully intend to do that, for many reasons, not the least of which would be honoring his spirit.”

Pringle’s death was caused by complications following heart surgery. “Basically, he went in for an operation that he thought would have him in the hospital for four or five days,” Novick explained. Six weeks later he died there. His final gig with the Black Eagles was on February 15, at the Regattabar at the Charles Hotel in Cambridge, Mass.

After joining the band in 1969, Pringle emerged as the Black Eagles’ musical leader and conscience. In 1967, Pringle and his wife, Norma, relocated to America and he soon joined the Exit Jazz Band with Stan Vincent, Stan McDonald, and Gil Roberts. Before long, the British cornetist was introduced to the fledgling Black Eagles.

New Orleans native clarinetist Tommy Sancton named that group in homage to the 1900’s-era Black Eagle Social Club, a black organization in uptown New Orleans. The original lineup was Tony Pringle, trumpet; Stan Vincent, trombone; Eli Newberger, piano; Dave Duquette, banjo; Ray Smith, drums; Tommy Sancton, clarinet; and Jim Klippert, trombone.

In 1970 the Black Eagle Jazz Band took up residence in Passim’s Coffee House across from the Harvard Coop in Cambridge, Mass. and played there regularly until breaking up in late spring 1971.* During their Passim’s residency in 1970, Pringle switched from trumpet to cornet – a move he never regretted. Later that year, the band added a singer—Bonnie Bagley. This ensemble, with Chester Zardis on bass, played at the 1971 Jazz & Heritage Festival in New Orleans, a prestigious booking that turned out to be the swan song of Sancton’s Black Eagles.

In 1971, after Sancton and Klippert left the band, the musicians regrouped and rebranded as The New Black Eagle Jazz Band. It didn’t happen overnight, but it started with a gig in Worcester by the Boston Bayou Jazz Band featuring Tony Pringle, Pam Pameijer, Peter Bullis and Eli Newberger from the old Black Eagle Jazz Band. Added were Stan Vincent on trombone, Stan MacDonald on clarinet and soprano sax, and Norm Stowell on string bass. But the band name didn’t stick.

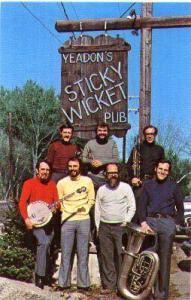

This same band—with Newberger switching to tuba and Bob Pilsbury added on piano— appeared on the S.S. Peter Stuyvesant at the Boston harbor on Sept. 30, 1971, playing their first-ever show as the New Black Eagle Jazz Band. In October of that same year the band began its famous residency at the Sticky Wicket Pub in Hopkinton, Mass.

The few changes of personnel until 2001, when Newberger left the band, were to the clarinet chair. In 1980 Brian Ogilvie replaced Stan MacDonald; in 1981, Hugh Blackwell took over; and Billy Novick replaced Blackwell on Thanksgiving 1986.

Flying high, the New Black Eagles became a fixture on the international jazz scene, bringing the sounds of New Orleans jazz to audiences worldwide. “Many observers regard us as the premier band playing in the traditional jazz style,” the band’s website proclaims. “We do regard ourselves as the ‘Keepers of the Flame.’”

Over its four decades, the band has released dozens of recordings including the Grammy-nominated On the River (1973). Their music has been featured in Ken Burns documentaries and on National Public Radio.

While the septet has entertained at major festivals from Newport to Edinburgh, the New Black Eagles remain beloved in New England. “Cape Codders enjoy recalling the many summer evenings when the band played beneath the stars on the grounds of the Heritage Plantation,” wrote JazzTimes critic Mick Carlon. “Pure bliss.”

Certainly, the band has impressed audiences everywhere with its enormous and eclectic repertoire from the 1920s and ’30s. The group regularly demonstrates a mature mastery of this music— from Louis Armstrong and Jelly Roll Morton to early Duke Ellington to Cole Porter, from blues to rags to popular songs of the Roaring Twenties.

The most recent personnel featured four original Eagles—Bullis, Pameijer, Pringle, and Vincent. Reedman Billy Novick has been with the band for the past 30 years. Tuba virtuoso Eli Newberger played with the band from 1971 to 2001. More recently, Herb Gardner took over for Pilsbury on piano and Jesse Williams joined on string bass.

When it came to remaining true to the Big Easy spirit, Pringle held the band’s feet to the fire, but he did so without rancor. “Tony was so much fun to be around,” Novick recalled. “He was warm, earthy, totally unpretentious, humble, extremely smart and inventive, great sense of humor, and, most of all, he had an irrepressible love of life.”

Pringle’s cornet playing was informally featured on tunes such as “Tight Like This” (not to be confused with “Tight Like That”) and “Michigander Blues.” His personal favorite tunes included Black Eagle staples such as “Weary Blues” and “Panama.”

“Musically, he had a huge impact on me, something I didn’t fully realize until now,” Novick remembered. “I’ve always been drawn to music that is emotional, passionate, and soulful, and Tony’s spare and soulful playing grabbed me instantly the first time I heard it. There is so much sincerity and integrity in his playing.

“He never tried to do something needlessly technical or intellectual in his playing just for its own sake the way many people do. His approach was that every note had great meaning, every note was part of your voice, every note expresses something.”

While some jazz musicians focus on technique, rhythmic or harmonic conception or extending the range of their instrument, Pringle never really cared much about that.

“He cared about the depth of feeling in the music,” Novick wrote. “That was the way he was going to reach people, and he was totally uncompromising in that. That approach gave his playing a uniquely wide and nuanced range of emotions—from sad or bluesy to joyously uplifting, with a million spots in between that I can’t even describe in words. I was incredibly lucky and grateful to be able to play so many gigs with him.”

Besides playing a unique “barking” style cornet, Pringle vocalized many tunes and his gravelly baritone seemed especially suited to the blues. “I love playing with Tony Pringle,” once said Black Eagles trombonist Stan Vincent. “Before every set he gives us the list of tunes we’ll be playing. You have to be on your toes because there are always different keys and different tempos.”

While understandably crestfallen, the surviving members of the New Black Eagle JB plan to play on, just as Pringle wished. Over the past 25 years, the band has performed perhaps 100 concerts without their leader on stage, Novick reported. The combo will do so again from 7 to 9 p.m., July 31, at Southgate at Shrewsbury retirement community, 30 Julio Drive, in Shrewsbury, Mass. And at performances on Nov. 9, at Amazing Things Arts Center in Framingham, Mass., and Nov, 18 at the Cultural Center of Cape Cod in Yarmouthport, Mass.

“We have a great stable of subs we’ve used that have done a great job,” Novick wrote. “None do what Tony did for us, but they bring other strengths. I’ve led the band when Tony wasn’t there, and it still definitely sounds like the Black Eagles.”

In fact, in January even before Pringle’s hospitalization, the clarinetist officially took over leadership responsibilities “because,” Novick said, “Tony wanted more flexibility to travel.” Or so he had hoped.

Related Stories:

Tony Pringle, Founding Member of the New Black Eagle Jazz Band, has Passed posted 5/4/18

Remembering Tony Pringle, 1936-2018 Printed 6/1/18

Russ Tarby is based in Syracuse NY and has written about jazz for The Syncopated Times, The Syracuse New Times, The Jazz Appreciation Society of Syracuse (JASS) JazzFax Newsletter, and several other publications.