Live concerts, location recordings and broadcast transcriptions of Duke Ellington and his Famous Orchestra from 1940 to 1963 reveal a distinctive body of work separate but parallel to the studio sessions. The music heard below highlights Ellington’s biggest stars recorded at dances, live shows and the legendary 1940 Fargo, North Dakota concert. Newly restored broadcast tapes from Duke’s Birthday Sessions recorded in Portland 1953-54 are also heard.

Live concerts, location recordings and broadcast transcriptions of Duke Ellington and his Famous Orchestra from 1940 to 1963 reveal a distinctive body of work separate but parallel to the studio sessions. The music heard below highlights Ellington’s biggest stars recorded at dances, live shows and the legendary 1940 Fargo, North Dakota concert. Newly restored broadcast tapes from Duke’s Birthday Sessions recorded in Portland 1953-54 are also heard.

Heat of the Moment

“Duke” Ellington (1899-1974) was an inventive, charming, gifted, hard-working jazz musician and composer of some 2000 musical works. Yet, considered solely as a performing bandleader and pianist he would be ranked a premier jazz musician — his other vast accomplishments aside.

Thanks to nationwide network radio hookups from the Cotton Club in Harlem, Duke Ellington and his Famous Orchestra achieved widespread fame by 1930. But they soon realized there was a significant difference between their studio sessions versus live concerts and dance dates.

Thanks to nationwide network radio hookups from the Cotton Club in Harlem, Duke Ellington and his Famous Orchestra achieved widespread fame by 1930. But they soon realized there was a significant difference between their studio sessions versus live concerts and dance dates.

The drive, enthusiasm and spontaneity of playing for dances or live audiences was muted in the theatricals, stage shows or terse constraints of a 3:00-4:00 minute 78 rpm disc — though Duke was a master of that medium. Fortunately, a plethora of excellent live performances and concerts were recorded on audiotape or transcription disc dating back to the mid-1930s.

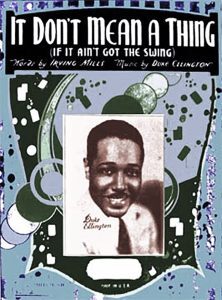

1) Los Angeles 1945 – It Don’t Mean a Thing & Air Conditioned Jungle.mp3

Beginning in the late-1950s mainstream record labels discovered the marketability of Ellington’s live shows. They issued albums made from tapes recorded at Newport and Monterey jazz festivals or from concerts in Paris, Cote d’Azur, Stockholm and Berlin. Today hundreds of live Ellington concerts and performances are available on CD, LP or subscription streaming services.

Fanning a Spark

From their 1927 opening at the famed Cotton Club nightclub in Harlem, Duke Ellington and his Famous Orchestra (as they were officially billed) set the highest standards for musicality, solo improvisation, imaginative ideas and classy presentation. Duke wrote and recorded thousands of tunes, performing all over the world, maintaining a continuously working orchestra for more than four decades.

It has rightfully been said that Ellington’s true instrument was his orchestra. He often created music to feature a specific instrumentalist, highlighting their particular talents and adapting or refining their themes. Yet he was a keyboard master second to none — subtle, imaginative, stylish and tasteful — his grace notes offering counterpoint and commentary.

One of America’s most productive composers, many of his tunes became durable jazz classics or popular standards of the American songbook. Incidentally, all the selections presented here were composed by Duke except for “Basin Street Blues.”

2) Fargo A – Mood Indigo, Sepia Panorama & Rumpus in Richmond.mp3

Hot in Fargo, 1940

Except for true Dukeophiles, the live dance and concert transcriptions from Fargo 1940 remain little-known treasures, though excerpts have occasionally been issued. They mark an elevated creative plateau for the Ellington orchestra that stretched into the mid-1940s. And Ellington had recently hired arranger, writing partner and aide-de-camp Billy Strayhorn and tenor saxophone master Ben Webster.

Only days earlier the multi-instrumentalist Ray Nance had joined the band, taking over the featured trumpet role of Cootie Williams — who had just left to join Benny Goodman. Ray also added jazz violin to Duke’s tone palette. Another fresh arrival was the remarkable young bass player Jimmy Blanton – who transformed and modernized Duke’s rhythm section.

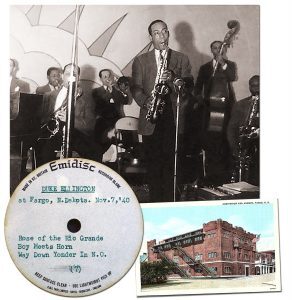

Fargo was unseasonably warm that November, a balmy contrast to their previous venue in frigid Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. The Crystal Ballroom (named for its central suspended glass reflecting-ball two feet in diameter) was the location for a remarkable performance preserved thanks to a couple of young music enthusiasts.

With Duke’s permission, Jack Towers and Richard Burris brought a portable disc recorder to the venue, cutting a microphone signal directly into the grooves of 33 & 1/3 rpm acetate discs during the concert and broadcast. As musicians heard some of the playbacks they rose grandly to the occasion.

The remastered LP tracks heard here — and Towers’ photos of the concert — are from the 1980 Grammy Award winning Book of the Month Club boxed vinyl set, Duke Ellington at Fargo, 1940 Live (BOMC-5622).

3) Fargo B – The Mooche, Harlem Airshaft & Ko-Ko.mp3

Stellar Soloists and the Small Bands

Having a stable roster of outstanding soloists allowed the composer to tailor custom materials for his gifted virtuosi. He crafted music highlighting their instrumental voices and personal motifs.

Fargo, and surviving the live recordings in general, feature Ellington’s most popular stars at their best. Because musicians often remained in the orchestra for decades, it was said that you could still be “the new guy” after five years.

Eager to let his thoroughbreds run, Duke and the record labels launched a series of spin-off groups led by his most illustrious stars: Johnny Hodges, Barney Bigard and Rex Stewart. The so-called Ellington Small Bands waxed 140 studio recordings between 1936-41. Consistently generating exquisite masterpieces, the sessions were usually seven instruments but ranged from 6-9 pieces, with Ellington or Strayhorn on piano — written, arranged and staffed by Duke.

Alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges (1907-70) was arguably the biggest star of the Famous Orchestra. A major stylist, he practically invented the alto as a jazz instrument, bringing unprecedented eloquence, articulation and lyricism to the saxophone. He was incomparable for emotional expression, economy of phrase, melodic creativity and exquisite tone, influencing listeners, critics and generations of saxophonists from Ben Webster to John Coltrane.

Johnny Hodges and his Orchestra was the most successful of the Ellington spin-off bands, waxing some 50 sides between 1937-41. After his departure in 1951 Johnny enjoyed international stardom but returned often to partner in creative endeavors.

Hodges and Duke devised endless, luscious melodies highlighting Johnny’s superlative, sensuous interpretations of blues and ballads. A couple such mini-concertos for alto were captured at Fargo: “Never No Lament” (also the melody for “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore”) and “Warm Valley.” The latter is included despite the intrusion of an off-mic broadcast announcer assuring us “a swell evening’s entertainment at the Crystal Ballroom in Downtown Fargo” with dancing until 1:00 am.

Never No Lament – Fargo 1940.mp3

Deeply influenced by Johnny Hodges, Ben Webster (1909-1973) was the first tenor saxophone star of the Ellington orchestra. A dynamic soloist, he was a catalytic force, galvanizing the saxophone section during three stints at productive peaks in 1935-36, 1940-43 and 1948-49. Nicknamed “The Brute,” he was said to be pugnacious when drunk – yet was a protective mentor for young bassist Jimmy Blanton.

Emerging from Kansas City in the mid-1930s, Webster was a leading stylist of the tenor saxophone. He quit the highly successful Cab Calloway Orchestra to join Duke in 1935. Known for his rich smoky tone and seductive sound, he was in steady demand for studio sessions and accompanying singers like Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday.

The call-and-response structure of “Cottontail” seems intended to feature his talent for rhythmic momentum, muscular tone, assertive lead and capacity to carry the whole band on his broad shoulders. Note that as the disc runs out, Ben was set-up for yet another solo chorus.

The unrivaled baritone saxophonist Harry Carney (1910-1974) was THE foremost early jazz stylist of the baritone instrument. He joined the orchestra in 1927 and remained until his death — shortly after Duke passed away in 1974. The Ellington saxophone sections were second to none, setting the pace in jazz for nearly 40 years.

Singer Ivie Anderson (1905-1949) performed for a decade with Ellington. In 1932 she was the first to sing “It Don’t Mean a Thing (If it Ain’t Got that Swing)” on record. Her warm personality and effervescent scatting made her very popular with audiences.

Ivie’s blues-inflected singing, depth of emotion and rich lower range brought her critical acclaim and favorable comparison to Billie Holiday. Her bubbly and flirtatious “Oh Babe, Maybe Someday” dates back to the Cotton Club era.

Oh Babe, Maybe Someday – Fargo 1940.mp3

New Orleans-born clarinet player Barney Bigard was hugely popular with audiences, retaining his Creole heritage and training during 15 years with the Famous Orchestra. His spin-off group, Barney Bigard and his Jazzopators, was yet another successful Ellington Small Band that cut two dozen excellent sides. After leaving Duke in the late-1940s, he worked intermittently for a decade and a half with Louis Armstrong.

“Clarinet Lament” was a feature for Bigard co-composed with Ellington. An extended variation on “Basin Street Blues,” it was also known as “Barney’s Concerto.”

Clarinet Lament – Fargo 1940.mp3

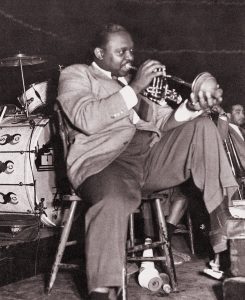

Rex Stewart (1909-1967) was a horn-playing star (cornet actually) in his own right — before, during and after his mere eleven years with Ellington. About twenty very good Ellington Small Band sides were issued under Stewart’s name.

Among his professional pursuits after retiring from music were working in radio and television and writing about jazz for publications like DownBeat and Playboy magazine. He subsequently owned a 100-acre dairy farm in upstate New York, operated a restaurant in Vermont, attended the Cordon Bleu cooking school in France and dedicated his life to fine cuisine.

Stewart and Ellington jointly conceived dozens of tunes exploiting his personal tonal vocabulary utilizing cup-mute effects, upward rips, baritone growls, flutter tonguing and his famed “half-valve” technique for bending, squeezing and smearing notes. The sassy “Boy Meets Horn” is a tasting menu of Rex’s sauces and seasonings for horn – and was the title of his posthumously published autobiography.

Boy Meets Horn – Fargo 1940.mp3

Birthday Sessions in Portland and “The Great James Robbery”

The relatively obscure Birthday Sessions (late April 1953 and ‘54) were recorded at McElroy’s Ballroom in Portland, Oregon during a series of dates celebrating Duke’s birthday (April 29th). They captured the high excitement of Ellington’s Famous Orchestra in live performance during an era of mostly dreary studio albums.

4) Portland Birthday Sessions – Sophisticated Lady & VIP’s Boogie.mp3

The sudden departure in 1951 of three longstanding Ellington comrades was a shock. Going their own ways were Johnny Hodges, trombonist Lawrence Brown (a veteran of nearly two decades) and drummer Sonny Greer who had been with him for 30 years.

Ellington rebounded quickly, raiding the orchestra of Harry James. In what the music press labeled “The Great James Robbery,” he purloined alto saxophonist Willie Smith and energetic young drummer Louie Bellson, a veteran of the Dorsey and Goodman bands.

Ellington rebounded quickly, raiding the orchestra of Harry James. In what the music press labeled “The Great James Robbery,” he purloined alto saxophonist Willie Smith and energetic young drummer Louie Bellson, a veteran of the Dorsey and Goodman bands.

Duke rehired valve trombone player Juan Tizol (1900-1984). Born in Puerto Rico, he was considered the most highly skilled musician in the band by his peers. Formerly with the orchestra from 1929 to 1944, Tizol was co-composer with Duke of “Caravan” and “Conga Brava.”

On the Portland roster were outstanding reed players Russell Procope, Jimmy Hamilton, Paul Gonsalves and Harry Carney. The brass section featured trumpeters Clark Terry, Ray Nance and high-note specialist Cat Anderson with trombone players Juan Tizol, Quentin Jackson and Britt Woodman — seen in this Three Kings promotional ad.

Caravan – Portland Birthday Sessions.mp3

“Floorshow” Ray Nance

For 23 years Ray Nance (1913-1976) filled several roles for Ellington. A fine trumpet player and jazz violinist, the diminutive musician and over-sized stage personality was an accomplished dancer, beguiling singer and all-around showman. An audience favorite, his crowd-pleasing antics garnered him long minutes of thunderous applause, numerous encores and the nickname ‘Floorshow.’

Nance was one of the most popular singers Duke ever presented. The Birthday Sessions vividly illustrate that by the 1950s Ray was a show-stopping entertainer and world-class ham. Note his intriguing amplified violin tone and attack in “Lay By” — a coy duet with Duke in Paris 1963.

5) Ray Nance A – Just Squeeze Me & Lay By.mp3

6) Ray Nance B – Tulip or Turnip & Basin Street Blues.mp3

Painting on a Broader Canvas

An accurate picture of the orchestra’s performances cannot omit Ellington’s extended suites and tone poems. By the late 1930s his composing and concertizing had moved well beyond the conventions of Jazz and Swing. He strove to find broader horizons for expression, attempting to expand the scope of his music. Nonetheless, he always left room in his scores for improvised elements — brilliant soloing, collectively devised head arrangements or spirited call-and-response.

Ellington composed numerous extended works and narrative suites: “Harlem,” “Reminiscing in Tempo’” “Liberian Suite,” “Deep South Suite,” “Suite Thursday,” “Such Sweet Thunder” and “Far East Suite.” He mounted three Sacred Concerts (1965, 1968, 1973) which he called “the most important thing I have ever done.”

The ambitious 45:00-minute tone poem “Black, Brown and Beige” was a three-movement suite for jazz orchestra. He presented it nearly complete on just one occasion to mixed response at Carnegie Hall in 1943. Accompanied by 29 pages of narrative text, it traces “the history of the Negro in America” from slavery to modern times, though the unorthodox format confused his fans and critics. Later, the segment “Black” was performed at the White House in June 1965.

7) Extended Work – excerpts from Brown – Carnegie 1943.mp3

Ellington loved to travel, and the orchestra loved performing. They may have toured further, longer, more often and widely than any other similar band. The live performances highlight their broad range — from lively dance beats for delighting the jitterbugs to Duke’s nuanced tone poems.

Performances were electric with excitement, spontaneity and confidence, hosted by a charismatic and urbane master of ceremonies. Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington quietly drew audiences close with modest flattery, summed up in his catch phrase “We do love you madly.”

Duke Ellington and his Famous Orchestra were beyond category for musical range, invention and depth of expression. Aside from his monumental studio discography, the live recordings are a massive alternate body of work offering an intimate view of Duke’s ensemble at its most inspired.

Closing Number: Rockin’ in Rhythm

This was one of Ellington’s many theme songs over the years, summarizing the orchestra’s strengths. The 1931 rendition — which this writer used as a radio broadcast theme for a decade — featured a short, ragtimey piano introduction. But in performance over the years it grew to a substantial prelude showcasing Ellington’s piano chops.

Duke’s call to assembly, “Rockin’ in Rhythm,” also served as a vamp for summoning his often-wayward flock to the stage at show start or after intermission. As heard in Fargo 1940, the ensemble portion was the vehicle for a tightly executed series of cascading crescendos.

Rockin’ in Rhythm – Fargo 1940.mp3

Sources:

Beyond Category: The Life and Genius of Duke Ellington, Hasse, Edward (Simon & Schuster, 1993)

Duke Ellington at Fargo, 1940 Live (Book of the Month Club, BOMC-5622, 1980)

JAZZ, Geoffrey C. Ward and Ken Burns (Knopf, 2000)

The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz (St. Martin’s Press, 1988)

Dave Radlauer is a six-time award-winning radio broadcaster presenting early Jazz since 1982. His vast JAZZ RHYTHM website is a compendium of early jazz history and photos with some 500 hours of exclusive music, broadcasts, interviews and audio rarities.

Radlauer is focused on telling the story of San Francisco Bay Area Revival Jazz. Preserving the memory of local legends, he is compiling, digitizing, interpreting and publishing their personal libraries of music, images, papers and ephemera to be conserved in the Dave Radlauer Jazz Collection at the Stanford University Library archives.