“A horn is just like the voice. Person have no voice, they can’t sing.” – Edward “Kid” Ory.

The question was: “How do you know what to play when you have no music in front of you.” It came last fall during a break at Ken’s Steakhouse in Framingham, Mass. from a lady who’d flown down from Anchorage to hear the Black Eagles. It was a fair question, which I tried to answer in a few words, but much later, I was left wondering just how I do manage to play without having the music in front of me.

Part of the answer may be the family genes. My grandfather on my mother’s side, William Lester Bates, was not only a Boston school principal but also music director and organist for the 2nd Congregational Church in suburban Newton, Mass. My dad, Myron S. “Vinny” Vincent, as a young violinist was advertised as the “Boy Wonder of New Hampshire.”

Another possibility: Growing up as the youngest child in a household filled with music, my mother played the piano, my two sisters listened and sang two-part harmony to records non-stop, and my dad had a great collection of his own. From my earliest years I loved music, and when I started trombone in the 8th grade, the only thing I could think about was playing music. I took a few lessons, but the most fun I had was sitting next to the record player and “playing by ear” -hour after hour.

It wasn’t until later, after playing in school and college bands and orchestras, reading charts on weekends with small dance bands, and spending a couple of years in a U.S. Army band, that I learned that to “play by ear” meant being able to play an instrument as easily as one can whistle or sing along to a tune. If you can hum along with the music, you can play an instrument by ear. It just takes time, determination and a lot of practice. It helps, too, to understand harmony, chords, and to have an ability to “hear” the music in your head.

– Playing without Music Charts –

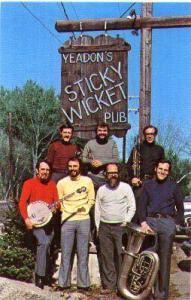

Trying to answer the question raised by the lady from Anchorage left me with a broader question: How do six or seven musicians playing together, especially those with no music in front of them, manage to create great music? Two jazz bands helped me answer that question. In 1957, the Chesapeake Bay Jass Band was the first band that introduced me to the unique qualities of “traditional” jazz, and it taught me what my place was in a band playing this kind of music.

The CBJB was led by Ed “Doc” Kittrell and his wife Jean Kittrell. Ed, a 6’ 4” WWII vet from Birmingham, Alabama, was an economics professor and self-taught cornetist who played in the style of King Oliver, staying close to the melody and never repeating himself. Jean, also from Birmingham and a music major, played foot-stomping, barrel-house piano and sang lusty Bessie Smith songs. They were then living in Norfolk, Virginia, Ed teaching in a local college, Jean raising their two little girls.

Their band also included locals Bob Fishbeck, reeds, and Ben Splan, tuba, and from across the bay at Ft. Monroe, Bob Giles, banjo, and myself on trombone. The music was straight ahead, New Orleans-influenced—basic chords, blues, marches, spirituals and some up-tempo tunes. The CBJB quickly became the toast of the town—busy on weekends playing for parties, the Norfolk Boat Club, and live radio and TV. The lesson learned here was, “Keep it simple.”

The Kittrells moved to Chicago in 1959. That summer I rejoined them for a tour of Germany and the Netherlands in a band they called the Chicago Stompers. Filling out the front line was John Carlson, clarinet, and in the rhythm section Carl Lunsford, banjo, and Don Franz, tuba. It was a very tight and hard-driving sextet. We rehearsed afternoons and played very long hours seven days a week. The young fans, hungry for American traditional jazz, were enthusiastically supportive. How the Kittrells approached their music, and in particular small ensemble playing, had a great and long-term influence on my playing. I still hear Ed crying out, “Too many notes!”

– The Subtleties of Ensemble Jazz –

The second band to teach me the subtleties of successful ensemble jazz was, and is, the New Black Eagle Jazz Band. In 1971, it was formed in Cambridge MA from the remnants of Tommy Sancton’s Black Eagle Band after Tommy and trombonist Jim Klippert left the Harvard Yard for the real world. There to pick up the pieces were Tony Pringle, cornet; Pete Bullis, banjo; C H “Pam” Pameijer, drums; and Eli Newberger, tuba. Joining them to make it a 7-piece group were Bob Pilsbury, piano; Stanley McDonald, reeds; and yours truly on trombone. Much of what I had learned from Ed and Jean Kittrell I was able to bring to the NBEJB, but this was a whole new experience.

From the start the NBEJB paid respect to the New Orleans and Chicago roots of jazz. Along the way, we added some rags, and soon were including some of Ellington’s early works. We force-fed ourselves to add more and more new tunes by taking “learning tapes” with us in our cars and scheduling rehearsals a couple of times a month to work out the chords and create our own arrangements. On stage, we stressed the importance of paying attention to each other, being conscious of where Tony was taking us, what the front line was doing, what the rhythm section was doing, the tempo, and especially the dynamics. Classically-trained chamber musicians pay attention to these same things, but I believe they are particularly important for musicians with no music in front of them.

Edward “Kid” Ory (1886-1973), one of the greatest New Orleans tailgate trombonists, had something to say about this subject. Ory was the lone trombonist on King Oliver’s 1926-7 recordings, held the trombone chair for two years in Louis Armstrong’s historic Hot Five recordings, and was there to celebrate Jelly Roll Morton’s Red Hot Peppers sessions.

Interviewed in 1960 at his home in California, Ory was asked his ideas about improvising: “Number one is to have a good tone….Then knowing what you’re doing and not overplaying…. It’s best to make less notes and make ‘em in the right place…. If it doesn’t fit and is done with a bad tone, you haven’t got nothing…. The melody is important. Listen to those Louis Armstrong records. He played melody with the band, then made up something different by himself…. In three-part harmony [cornet-clarinet-trombone], somebody has to have the straight melody, the other two harmonize.” – (Richard B. Hadlock, The Complete Kid Ory Verve Sessions, 1999)

The Boston-based New Black Eagle Jazz Band celebrates its 45th anniversary this fall.

Related: Tony Pringle, Founding Member of the New Black Eagle Jazz Band, has Passed, Remembering Tony Pringle, 1936-2018, Peter Bullis, Banjoist for the New Black Eagle Jazz Band, has passed, New Black Eagles Remain Aloft, Jean Kittrell The “Red Hot Mama” of Dixieland Jazz, Has Died

Stan Vincent has been playing traditional jazz trombone in leading bands since the 1950s. Most notably as a member of The New Black Eagles Jazz Band.