Set forth below is the sixtieth “Texas Shout” column. The concluding installment of a three-part essay, (Part 1, Part 2,) it first appeared in the April 1995 issue of the West Coast Rag now known as The Syncopated Times. The text has not been updated.

Set forth below is the sixtieth “Texas Shout” column. The concluding installment of a three-part essay, (Part 1, Part 2,) it first appeared in the April 1995 issue of the West Coast Rag now known as The Syncopated Times. The text has not been updated.

The snare drum snuck in there somewhere, though it had nothing to do with jazz (but it may have helped me with the washboard, with which I later dabbled on an amateur basis). I was still a trombonist when I first reported to the motley assemblage laughingly referred to as the Swarthmore College Marching Band.

Swarthmore had only 900 students at the time, so the band was, to put it kindly, a loosely organized, less than imposing ensemble. We would gather Saturday morning before the game with whoever showed up (as many as 30 on a good day), pick a few tunes for half-time and rehearse our “formations.” Eventually, we would walk out on the field and rearrange ourselves into a series of amorphous globs while the stadium announcer, who had been carefully primed, triumphantly told the audience what we were supposed to be representing.

The snare drum is the crucial instrument in such high-jinks because it is setting the time to which the others are marching in step. Fortunately, Ted, our snare drummer, was all that we could have hoped for, but he graduated at the end of my freshman year. (Believe it or not, I next saw Ted 32 years later at Friday Harbor when he walked out of the audience after a Rent Party Revellers’ set and re-introduced himself.)

Not to worry. The incoming freshman class included Freddie, who appeared to have impeccable credentials as a drummer, so we gathered that fall for our first drill with confidence.

Snare drummers in a marching band commonly strap the drum to their left leg to keep it from swinging around while they’re simultaneously marching and drumming. Freddie, it turned out, had done lots of concert work, but had never attempted to drum with his snare bobbing up and down on his leg.

After an hour of stumbling and skipping across the gym trying in vain, along with the others, to march to the spastic rhythms Freddie was emitting, I approached the long-suffering area music teacher who had been dragooned by Swarthmore into the thankless job of trying to make the Marching Band into something that might get by on a foggy day. The following conversation ensued:

“How’s about me strapping on a drum for the game tomorrow to help Freddie out?”

“Can you play a snare drum?”

“No, but I can keep steady time. Freddie can do all the fancy stuff.”

After a prayerful glance Heavenward for aid in appraising his obviously distasteful alternatives, he agreed. Thus, I became, for the next three years, probably the only person who ever led a college band drum section without being able to play a sustained roll. I still can’t and never did learn what a paradiddle is.

After a prayerful glance Heavenward for aid in appraising his obviously distasteful alternatives, he agreed. Thus, I became, for the next three years, probably the only person who ever led a college band drum section without being able to play a sustained roll. I still can’t and never did learn what a paradiddle is.

While we’re on miscellaneous instruments, I became enamored of the bass saxophone as a result of two fine Riverside LPs, a contemporary one by Carl Halen’s Gin Bottle Seven and a reissue by the California Ramblers. In the 1960s, the bass saxophone was even rarer than it is now. In fact, I had never even seen one.

However, I figured that I’d have a better chance of finding one in Boston than in Wilmington. So, one morning shortly before graduating from business school, I put in the four hours required to call every music store in the Boston yellow pages.

Two of them had bass saxophones on hand. One horn had been ordered new from France, but had been sitting unpurchased for so long that the owner, unwilling to let a sucker off the line, offered to knock $360 off the retail price if I’d drive downtown and buy it. The other was a used Conn that the owner had, mirabile dictu, acquired that very morning and had not yet priced – and his store was across the street from the first one!

I did not know how to play a saxophone, my sole experience with reed instruments being a few squawks I had elicited from a World War II metal clarinet that somehow wound up in my growing stack of instruments. So, I asked the reedman in my band if he would be my expert in making the choice.

Tom tried both, stating that the Conn was every bit as good as the new horn, and that if he could get such a bargain on a baritone sax, he’d buy it in a minute. Thus for $295, I got a bass saxophone, a hard case, a box of reeds, an instruction book, an adjustable metal stand with rollers, and a harness so you could play it standing up if you had the physique of Godzilla. The store’s prices were so good that I also purchased a straight soprano saxophone that day for another $95.

I was driving an MGA, which barely has room for two people, let alone a bass saxophone, so we folded back the roof, sat the horn upright in Tom’s lap (where it topped out at a level about twice as high as the car), pulled out into the bumper-to- bumper Boston rush hour traffic and crept back to Cambridge as a sudden downpour soaked us both (but not the horns).

The hard case was the size of a small coffin, and our apartment was about the size of a large broom closet. The only place big enough to store my bass sax was the middle of our living room floor, where it resided for the few months left until we moved.

If you know how to play Dixieland tuba lines, you can translate them to the bass saxophone fairly easily. I played my first gig on it less than a week after buying it. It’s really a fun instrument to play but, as with the trombone and tuba, the demands of the cornet and piano have kept me from it except for one gig about twenty years ago.

Actually, piano is my first love. Next to spending time with my wife Nancy, playing piano is the thing I enjoy most.

I quickly learned to sight-read lead sheets on piano, but never had to do much in the way of reading piano scores because ragtime, the only piano music that interested me much, was almost completely unobtainable commercially during the 1950s. I remember staying up two straight nights until the wee hours, in those pre-photocopier days, handcopying Scott Joplin’s “The Cascades” that a friend lent me, because it was the only way I knew to acquire the music to it.

The reading came in 1963, when Max Morath privately published 100 Ragtime Classics, a thick folio containing a cross-section of the best Missouri Valley classic rags. I got four copies, so I could play everything in this marvelous volume without having to turn any pages.

Max had picked rags ranging from easy to demanding, and it was that variety that got me through the agonies of getting comfortable with reading. I worked on the easier numbers until I was at home with them and then discovered that a few slightly harder ones in the volume had thereby come within my grasp, and so on through the entire contents.

Now, because I am used to the conventions of ragtime scoring (and because I never bother with much of anything else), I can pick up a fairly challenging rag at sight and usually get something out of it. However, if you put some other kind of music in front of me – say a simple church hymn scored in half notes – I may still wind up puzzling it out the way I did so many years ago with “Maple Leaf Rag.”

Piano comes much more easily to me than the cornet, which I find to be a devilishly high maintenance instrument. If someone had told me, back in the mid-sixties when I first turned to cornet, that I would one day be the cornetist with a major-league Dixieland band appearing regularly at national festivals and cruises, I’d have wondered what he was smoking.

Much as I enjoy playing with the Red Lions, I begrudge the practice time I have to put in on the cornet. I told myself, back in 1964, that I would hang up the horn after 25 years (if the Red Lions lasted that long) and concentrate on the piano.

Then, in 1982, The Rent Party Revellers came along. The RPR has proved to be a dream come true for me. I’m having too much fun with the Revellers to think about stopping. As long as they stay on the boards, I’ll probably keep squaring off against the cornet for an hour or so each day.

I suppose that most aspiring Dixielanders hope for a day when they can get up on a stage with a band full of ace jazzmen/ jazzwomen, play the living daylights out of a bunch of tunes, and leave the crowd cheering. I’ve been very fortunate in that respect. As a member of the Revellers, that experience now happens to me several times a year. Let me tell you, it’s just as much fun each time as it was when the Revellers first took the stage in December 1982.

Anyway, that’s the saga of how one Dixieland-struck kid fought his way into playing music, via a series of coincidences, determination, and jerry-built ad hoc musical systems, in those days before the advent of high school stage band programs and jazz colleges. I think many Dixielanders my age could tell you similar stories.

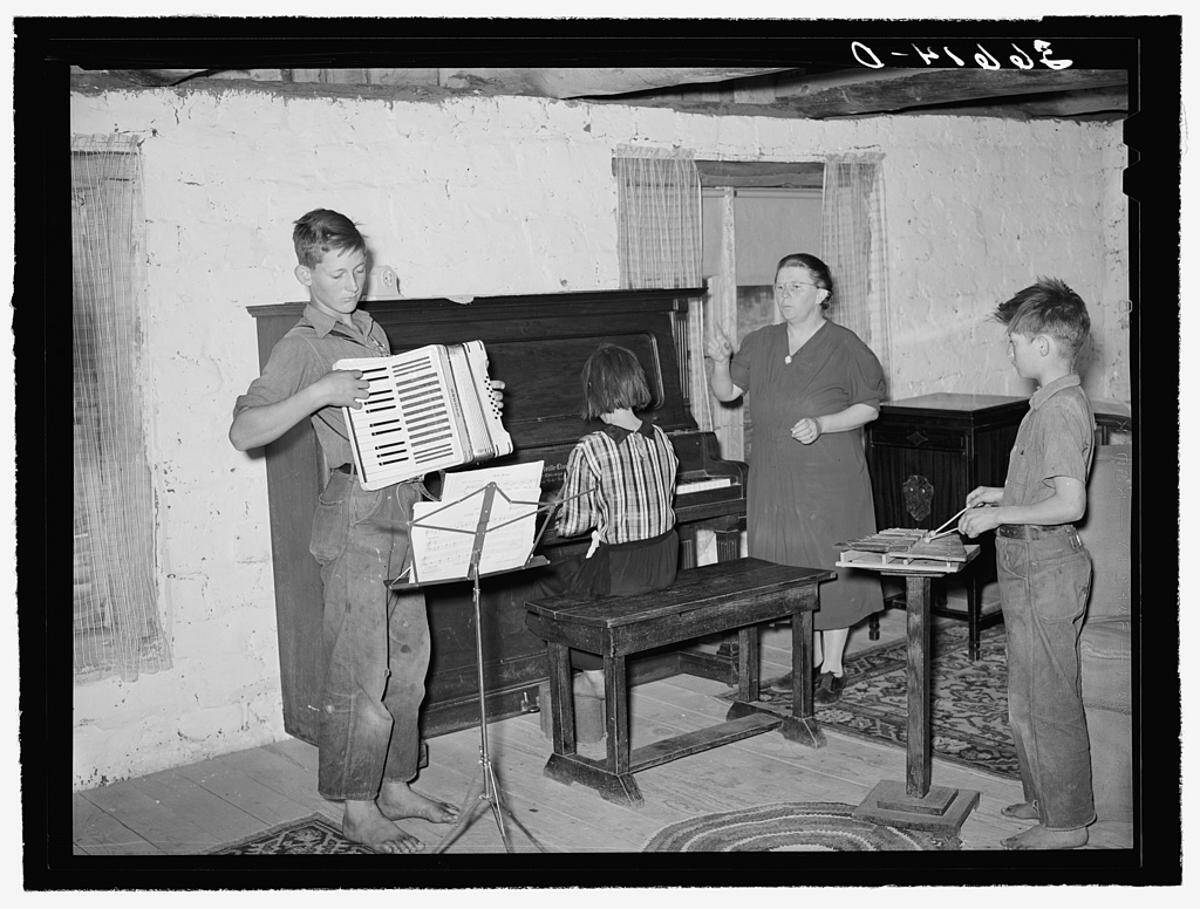

Now in our late fifties, we’re too old to start over. Many of us missed out on the teaching devices widely used today in public schools that could have given us better technique more quickly. The ones we devised on our own were constructed of dreams, spit and baling wire. What we did was analogous, in a way, to experiences of some early Dixielanders who, entranced by jazz, made guitars out of cigar boxes and drummed on kitchen chairs.

On the other hand, we were forced to pay close attention to what we wanted to say with our music, because we were on our own to figure out how we were going to get the chops to say it. Maybe that’s not too bad a trade-off, after all.

Want to read ahead? Buy the book!

Want to read ahead? Buy the book!

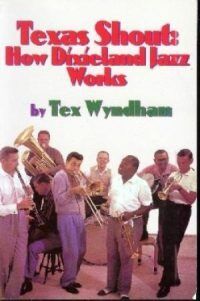

The full run of “Texas Shout” has been collected into a lavishly illustrated trade paperback entitled Texas Shout: How Dixieland Jazz Works. This book is available @ $20.00 plus $2.95 shipping from Tex Wyndham, On request, Tex will autograph the book and add a personalized note (be sure to tell him to whom the note should be addressed).

Tex Wyndham’s 3 CD Guide to Dixieland with music and commentary is available for $20 plus $2.95 shipping. The separate CD, A History of Ragtime: Tex Wyndham Live At Santa Rosa, is available for $13.00 plus $2.00 shipping. On request, Tex will autograph the inner sleeve and add a personalized note (be sure to tell him to whom the note should be addressed).

Send payment to Tex Wyndham, P.O. Box 831, Mendenhall, PA 19357, Phone (610) 388-6330.

Note: All links, pictures, videos or graphics accompanying the Shouts were added at the discretion of the Syncopated Times editorial staff. They did not accompany the original columns and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of Tex Wyndham.

From roughly 1970-2010, Tex Wyndham was: (1) one of the best-known revivalist Dixieland jazz musicians in the US, as cornetist, pianist and bandleader, (2) one of the best-known ragtime pianists in the US, and (3) one of the most respected critics in the US of Dixieland jazz, ragtime, and related music. He is the only person about whom all three of those statements can be made.