Set forth below is the fifty-eighth “Texas Shout” column. The initial installment of a three-part essay, it first appeared in the February 1995 issue of the West Coast Rag.now known as The Syncopated Times. The text has not been updated.

Set forth below is the fifty-eighth “Texas Shout” column. The initial installment of a three-part essay, it first appeared in the February 1995 issue of the West Coast Rag.now known as The Syncopated Times. The text has not been updated.

So that I could find it conveniently in my files, I gave the title “Learning To Play” to the full collected three sections of this article. I don’t want to oversell what follows, but you might find it interesting to know that, based on the amount and type of feedback I received, I believe that “Learning To Play” was the most popular of all the “Texas Shout” columns. This result surprised me because, though I tried to include some material of broader interest (such as the discussion below of the four “magic chords”), I considered it basically a fluffy good-natured piece of nostalgic chit-chat.

After writing the last essay (#56 & #57) I told the publication’s then editor, Woody Laughnan, that (1) I felt I had covered all of the topics I really wanted to discuss in “Texas Shout” and (2) I was accordingly closing down the column. Woody was unhappy at hearing such news and asked me to keep “Texas Shout” going a while longer. I wound up scratching out copy for eighteen more issues before tossing in the pen. “Learning To Play” was my first effort in that direction.

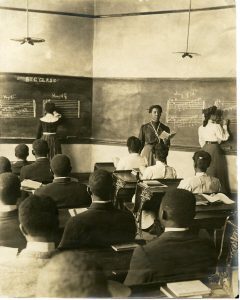

The techniques used to teach musical instruments today are nothing short of amazing. School-age children are regularly taught to sight-read flypaper, spend all evening in the screech range, and generally execute with regularity things thought to be impossible in the twenties.

The techniques used to teach musical instruments today are nothing short of amazing. School-age children are regularly taught to sight-read flypaper, spend all evening in the screech range, and generally execute with regularity things thought to be impossible in the twenties.

This phenomenon is an outgrowth of the stage band movement, which really started to grab hold in our high schools in the sixties. Although the teachers thereof typically pay no attention to Dixieland, believing that jazz really started with Charlie Parker, one has to admire what they’ve taught their charges and to wish that such instrumental coaching had been available in our day.

This thought got me to reminiscing about the home-grown ways in which many of today’s veteran Dixielanders, obsessed with a desire to play our music but unable to find anyone who would teach it to us, learned how to operate our instruments. I’ll share some of my own stories on that topic with you in a moment, but before I do so, I want to make a point about technical virtuosity and jazz playing.

No one in his right mind denigrates technique. We all practice diligently to maintain the technique we have and to try to expand it.

All jazzmen yearn for the chops to reach up one more half-tone, play one more closing chorus, toss off a dazzling run, etc. We can’t help feeling a touch of envy when we hear highly skilled jazz technicians, and when we see their startling accomplishments being rewarded with thunderous applause.

From an audience viewpoint, technique is readily recognizable, easily accessible, and highly exciting. If a trumpeter steps up on his first solo and hits double-high Z-sharp with a big fat tone and ringing volume, and then manages to squeeze 473 cleanly articulated notes into every beat, even a tin ear in the crowd will be forced to take notice.

Such an accomplishment deserves recognition and gets it. Even so, a Dixieland fan should be careful to remember a number of things regarding instrumental technique.

First, there are many impressive players who are unable to resist putting their entire bag of tricks into every solo. One need not disparage their talents to find this practice getting old fast. Once you’ve shown the audience everything you can do on the first tune, what’s left for the second?

When I encounter such a player, I usually jump to my feet after the opening number, applaud warmly on the next, begin to experience deja vu on the third, and start looking to see who’s playing at the other venues on the fourth. It’s not how many notes you play that counts, but playing the right notes that pays off in jazz. Technique is useless if it is not put to the service of creating a distinctive, valid and fresh vision of the material.

Second, the rules of Dixieland were set down before these super-fancy techniques were known to exist. Someone who deploys, to an excessive extent in a Dixieland framework, the busy lines and extreme ranges available to modern technicians will upset the balance of the band.

There is a place, to be sure, in Dixieland for dramatic highs, fleet runs and angular out-of-chord notions. For example, I wish I could hit a high concert E♭ on my cornet. I encounter occasions when it seems right to do so; instead I need to invent an alternative way to make my musical point.

However, such occasions don’t come up that often, and if I spent the whole gig up around that E♭, the other Dixielanders in the band would be unable to do their jobs, which is to find something to blend with my lines. In short, compared to more advanced jazz forms, where instrumental virtuosity is more highly valued for its own sake, there aren’t so many times when it will really advance the ball for a Dixielander in a meaningful way.

In fact, many immortal Dixielanders had techniques that probably wouldn’t pass muster in today’s high school bands. Jim Robinson is one of Dixieland’s most imitated trombonists, not because of the notes he played (which are fairly easy to replicate), but because he had a matchless gift for selecting notes that drove the combo forward relentlessly. Muggsy Spanier is reported to have joked that he never hit a high C in his life, but that doesn’t keep jazz history from placing his name high on the list of all-time hot lead Dixieland horns.

Third, while all Dixieland players would like to have more technique, it should be recognized that, in the wider musical community, technical virtuosity is fairly common. Schools like Juilliard, Berklee and North Texas State turn out dozens of musicians annually who have technique coming out their ears and who possess much more of it than the typical Dixielander, including many famous ones, can begin to approach.

If you really want to applaud technique, you’re reading the wrong publication and attending the wrong concerts. You should be listening to, among other things, modern jazz or classical music. If you want to listen to Dixieland, you should be looking for bands and musicians who can surprise you, who seem always to have something special to say, even if they manage to say it with a couple of half notes in the mid-range followed by a long rest.

Stage bands weren’t around in 1945 when I was eight years old and in the fourth grade at a suburban public school. That fall, Mt. Pleasant School sent around a letter to parents saying that piano lessons were available for a nominal charge. My parents signed me up, even though we did not then have a piano at home, over my protests (the lessons were given on part of the lunch hour and I wanted to go out on the playground).

We took the “Visual Method.” There was one piano in the room, an upright with its keys wired to a replica of a keyboard on its top. We sat at wooden blocks carved to represent about two octaves on a piano keyboard.

The teacher struck a note on the piano, it would light up on the replica, and we would place our fingers at that spot on the wooden block. Once a period, we came up to the real piano so the teacher could see if we were doing it right.

Those of us who didn’t have pianos were given folding cardboard keyboards to take home. We would spread it out on the dining room table and practice fingering. (I still have my keyboard, though fortunately for me, my folks acquired a piano shortly thereafter from a business associate who was getting rid of his furniture following a divorce. For that matter, I still have that piano.)

I took the Visual Method through the fourth grade and for a few weeks into the fifth. It taught me how to read music as well as how to recognize a major, minor and seventh chord (but it did not teach any theory or chord progressions).

My parents then had me take private lessons, but within a few months I was bored by the finger exercises and simplified classical pieces with which I was confronted. We did not have much music in our home, and the titles meant nothing to me. Besides, none of my friends wanted to hear me play “Santa Lucia” or “The Blue Danube.”

So I stopped taking lessons. However, just about that time, I heard some piano music on the radio. (Remember, in the late forties, commercial radio played all kinds of popular music, by contrast to today’s scene, where rock predominates.) I had no idea what it was, but I thought it sounded great. I wanted to play piano that way.

I went to Wilmington’s largest music store where, believe it or not, the last song plugger in our city was still going strong. Able to read anything at sight, she stood behind a small counter with a piano and piles of colorful music sheets displayed on racks behind her. If a piece caught your eye, she would demonstrate it for you on the spot.

I tried describing the music I’d heard on the radio. I had no idea that it had any kind of a name, but the lady was very patient with this enthusiastic child. (I told this story once at the office, only to have a colleague speak up and say “That was my mother!” Small world.)

She eventually figured out that I was probably talking about ragtime, a type of music that was then dead as a doornail. She walked behind her music racks and started rummaging through a drawer. I could see her blowing dust off the song sheets as she examined them.

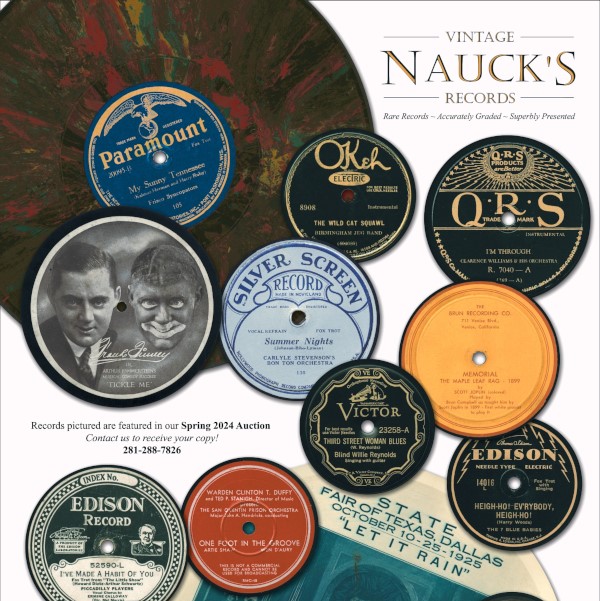

She emerged with reprint copies of “Smoky Mokes” and “Maple Leaf Rag.” Once she played them for me, I knew that this was the music I’d heard and gleefully snapped up both of them.

You couldn’t keep me away from the piano. My parents, bless their hearts, must have had the patience of Job, because they never once complained about hearing these same two tunes over and over, hour after hour.

“Smoky Mokes” is a fairly easy cakewalk which I soon got under control, but “Maple Leaf Rag” is hard and my little hands had a lot of trouble pushing down those thick cluster chords in the trio. It would take me about forty-five minutes just to get through it once (played accurately up to tempo, it should take about three). Then as I only had the two tunes, there wasn’t much else to do but try it again. Never a word from Mom or Dad, unless I was holding up dinner.

I couldn’t find any more ragtime commercially in those days, but I did buy some simplified pieces that sounded like they had some similar elements. I remember particularly two easy-to-play boogie woogies. Still, I was limited to the printed scores until an unforgettable day that opened wide the doors of popular music for me.

I was in junior high school and a member of the cast of a Saturday morning kids’ radio show on WILM. I would banter with Harry Hubbel (dressed as Wilmo The Clown before a live studio audience) and maybe play a little piano or do a recitation.

One day at rehearsal, when just the two of us were in the studio, Harry said “Tex, do you know how to play piano by ear?” “No.” “There’s nothing to it. You can play any song using only four chords.”

I was dumbfounded. Remember, my Visual Method had taught me nothing about chord progressions. However, I was certain that more than four chords were needed to play all of the songs in the world, and I said so. Harry then left me slack-jawed by sitting down at the piano and running off a long string of popular hits, all of which needed only four chords.

I now realize that the basic building blocks of pre-rock pops are a major chord on the tonic note (called a I chord), a major chord on the fourth note of the scale (a IV chord), a seventh chord on the fifth note of the scale (V7) and a chord on the second note of the scale which might be either a seventh or a minor chord (II7 or IIm). Thousands of twelve-bar blues use only the I, IV and V7 chords. Harry, of course, was selecting only tunes that would work with the four basic ones, but he could go on like that indefinitely.

Suddenly the whole universe of music seemed within my grasp. I quickly memorized the chords, which were in Harry’s favorite key of F: F, B♭, C7 and either G7 or Gm.

Now I no longer had to live with “Smoky Mokes” and “Maple Leaf Rag.” I would pick out the melody to a tune I wanted to play. If it wasn’t in F, I would immediately transpose it to F, so that I could apply the “magic chords” to it.

(Although I can now play the piano easily in any of the common jazz and ragtime keys, to this day F seems especially comfortable for me at the keyboard. Moreover, it took me a while to become completely weaned from F.

When I got to college, and was initiated into jamming Dixieland tunes, I’d be thinking something like: “If this tune were in F, the next chord would be a D♭ – three whole tones down from F, but we’re playing in A♭, so that means I need to go three whole tones down to an E chord.” I still can’t believe I could make that intricate thought process work while playing at high speeds, but it got me through until I reached the point where I automatically knew progressions in the different keys.)

You would be astonished at all the tunes that got played with Harry’s four chords. “Stardust?” No problem. “1812 Overture?” Piece of cake.

However, my ear soon began telling me that, for some tunes, none of the four chords would work. I tried others. If I was harmonizing a D note in the melody, I would try a D chord of some kind. If that didn’t work, I’d try some other chord that had a D in it. Eventually after months of this process, I taught myself, by brute force, the circle-of-fifths chord progression, the basic progression used in American popular music prior to the Beatles.

By this time, as a result of reading They All Played Ragtime, I had discovered what ragtime was, and via 78s by The Firehouse Five Plus Two, I was into Dixieland jazz. I couldn’t do much more than play melody and chords to tunes, but a friend of mine at school had taken lessons in popular piano at a downtown studio. His name was Rick Cordrey, later to spend fifteen years as pianist for my Red Lion Jazz Band and then to become the first 88er for the Buck Creek Jazz Band.

In another session I’ll never forget, Rick was kind enough to come to my home after school and show me some of the tricks he’d learned at the Horace Hustler studios. I came away with one special effect for each hand – voicing the treble in octaves to get a bigger sound, and a “fake bass,” rolling my left hand without moving it on the keyboard, to get a light-but-accurate rhythm at fast tempos.

I practiced these incessantly (for some years I could play treble runs faster in octaves than in single notes, just the reverse of what is comfortable for most pianists). However, now that Rick had alerted me to looking for pianistic tricks, I was able to pick up others from records and even invent a few of my own.

I was on my way. My patchwork method was a cruder school than Juilliard, and I’ve often wished that I had more formal lessons (it sometimes took me years of fooling around at the keyboard before I understood a fact that a teacher could have taught me in five minutes), but at least I had enough grounding to play some gigs, form a band, and even investigate methods of getting sounds out of other instruments than the piano.

Want to read ahead? Buy the book!

Want to read ahead? Buy the book!

The full run of “Texas Shout” has been collected into a lavishly illustrated trade paperback entitled Texas Shout: How Dixieland Jazz Works. This book is available @ $20.00 plus $2.95 shipping from Tex Wyndham, On request, Tex will autograph the book and add a personalized note (be sure to tell him to whom the note should be addressed).

Tex Wyndham’s 3 CD Guide to Dixieland with music and commentary is available for $20 plus $2.95 shipping. The separate CD, A History of Ragtime: Tex Wyndham Live At Santa Rosa, is available for $13.00 plus $2.00 shipping. On request, Tex will autograph the inner sleeve and add a personalized note (be sure to tell him to whom the note should be addressed).

Send payment to Tex Wyndham, P.O. Box 831, Mendenhall, PA 19357, Phone (610) 388-6330.

Note: All links, pictures, videos or graphics accompanying the Shouts were added at the discretion of the Syncopated Times editorial staff. They did not accompany the original columns and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of Tex Wyndham.