Set forth below is the sixty-fourth “Texas Shout” column. The concluding installment of a two-part essay, (part 1,) it first appeared in the August 1995 issue of the West Coast Rag. Because the text has not been updated, I should mention that “This Month’s Records” was a record review column that I discontinued in 1998.

Set forth below is the sixty-fourth “Texas Shout” column. The concluding installment of a two-part essay, (part 1,) it first appeared in the August 1995 issue of the West Coast Rag. Because the text has not been updated, I should mention that “This Month’s Records” was a record review column that I discontinued in 1998.

The essay deals with the effects of the fact that a large majority of today’s Dixieland musicians are in their mid-sixties or older. Many of them, including some movers and shakers in the field, are behaving as if the scene hasn’t changed since the 1950s when they first became interested in the music.

At that time, only a dozen years into the Dixieland revival, there were still styles of Dixieland that were struggling to regain the stage and many worthy but neglected tunes that deserved resurrection. As the first installment of today’s column ended, I was citing examples of the way the 1950s mindset is distorting the current scene.

Incident One. Not long ago I was playing a gig with a lineup that included a musician in his twenties. A skillful player, he has become deeply interested in our music to the point where he is now an official of a Dixieland club and a member of a festival-quality band. However, his regular combo is one of those that worships at the cult of obscurity and will not add a tune to its book if it thinks that the number is currently being played by another band anywhere in the world.

We were working with a roughly sketched tune list, but about halfway through the second set, we hit one of those what-shall-we-play-next stage pauses. I suggested “Memphis Blues,” but our young friend didn’t know it. Undaunted, I tried “Ida,” but with the same result. Astonished that anyone could reach his level of ability without mastering such staples, I gave up at that point and let him make the calls for the rest of the evening.

Incident Two. A while back I was on lead with a combo that finished a set with a rousing “Clarinet Marmalade” to the general approval of all present. One of the sidemen was an excellent seasoned Dixielander, a member of one of the most famous and widely traveled units on the circuit. As we left the bandstand, he mentioned to me in a bemused way that he didn’t think he’d played “Clarinet Marmalade” in fifteen years.

My jaw just about hit the floor. I spent the next break, and a fair amount of time since, asking myself two questions: How could such an experienced in-demand artist have gone so long without playing “Clarinet Marmalade” or any other tune in the standard repertoire? Why would anyone want to go fifteen years without once participating in a rendition of such a can’t-miss hot number as “Clarinet Marmalade ?”

My jaw just about hit the floor. I spent the next break, and a fair amount of time since, asking myself two questions: How could such an experienced in-demand artist have gone so long without playing “Clarinet Marmalade” or any other tune in the standard repertoire? Why would anyone want to go fifteen years without once participating in a rendition of such a can’t-miss hot number as “Clarinet Marmalade ?”

What’s going on here? If you put those two incidents together, you can see the answer.

Those top thirty combos we listed at the beginning of this column consist of a pool of some 200-300 musicians, mostly age 50 or over. The majority thereof is on the revivalist side of the fence and came to the music in the 1950s and 1960s.

At that time, it was still true that, by and large, the music of such greats as Oliver, Armstrong, Morton and Dodds was not in common currency in the Dixieland community. Bands such as Turk Murphy’s, Bob Scobey’s, the Red Onions, the Dixieland Rhythm Kings, and Firehouse Five (all of which also played the standards, don’t forget) were introducing such material to the wider Dixieland audience by putting it into their regular books and recording it.

These outfits hooked a later generation of musicians, many of whom proceeded to develop and then religiously embrace an absurd dogma: that obscurity in itself is a virtue, that there is something wrong with playing the established Dixieland favorites, and that a band is making unacceptable concessions to commerciality if it plays requests or anything else that the audience actually wants to hear. They have been assiduously following these misguided principles for the past 20-30 years.

In the process, they have succeeded in virtually stamping out the standard repertoire from large segments of the Dixieland community, so that veteran musicians can now go fifteen years without playing a given standard. Even worse, the few young people who are attracted to our music are coming in somewhere in the middle, unexposed to the selections that once formed a common jazz vocabulary, learning tunes that nobody else knows, and unable to be fully functional outside of their regular bands. Can anyone in his right mind think that this situation is a healthy long-term one for Dixieland?

In the process, they have succeeded in virtually stamping out the standard repertoire from large segments of the Dixieland community, so that veteran musicians can now go fifteen years without playing a given standard. Even worse, the few young people who are attracted to our music are coming in somewhere in the middle, unexposed to the selections that once formed a common jazz vocabulary, learning tunes that nobody else knows, and unable to be fully functional outside of their regular bands. Can anyone in his right mind think that this situation is a healthy long-term one for Dixieland?

(Frankly, if a jazzman tells me that he won’t play the standard repertoire, I believe he’s really saying that his stock of imagination and creativity has become so exhausted that he can’t show you something you haven’t heard before without the help of a tune that’s new to you. He’s running on empty.

This topic actually belongs in a separate column, another one that’s really too depressing to write. However, anyone who listens to as many records as I do should have no trouble concluding that a disheartening number of well-known revivalist Dixielanders have long since said everything they have to say and have been reworking the same favorite licks through the same solos for years. This problem is less evident at in-person performances, where the immediacy lets you forgive chord-running more easily, but it hits you between the eyes on the records.)

Now that the standard repertoire has been driven underground, have the obscurantists replaced it with anything? No. The lemming-like search for more unknown titles just goes on. To show you what I mean, let me recount one more true-life adventure. All new recordings purchased for our collection get their first spin while we’re eating breakfast. We have them in the air, with one ear on them, just to get the lay of the land before we do the hard listening.

When records come in for review, if they are clearly appropriate for my review column, they go on the review shelf. However, if there is any doubt, they also get the breakfast treatment. We run through each one fully once, and if it turns out to be outside my scope of interest, I don’t review it but just note its availability in “This Month’s Records”.

When records come in for review, if they are clearly appropriate for my review column, they go on the review shelf. However, if there is any doubt, they also get the breakfast treatment. We run through each one fully once, and if it turns out to be outside my scope of interest, I don’t review it but just note its availability in “This Month’s Records”.

My wife Nancy is a knowledgeable and perceptive listener. We frequently comment to each other on various aspects of the breakfast serenades.

Sometimes the review copies turn out to be modern jazz of a type so jarring, noisy and unpleasant that it sounds like 65 minutes of someone torturing a cat while a string bass noodles in the background. Nancy and I both wonder if anyone really enjoys such musical anarchy, but she recognizes that I need to check out the album all the way through, just to make sure the last few tracks don’t make an unlikely turn into Dixieland territory.

Not long ago, we acquired one that seemed highly promising. The personnel consisted of top Dixielanders, artists frequently seen at festivals and mentioned in these pages. Several are long-standing friends of ours, so we anticipated delightful sounds as an aid to digestion that morning.

We were soon disillusioned. The disc was rife with pedestrian material, obscure to be sure, but deservedly so – trivial vintage pops, imitations of personality entertainers, marginalia from the old days – rendered with no spark or buoyancy whatsoever.

As I was suffering through yet another soggy version of a tune better left in its grave, and wondering why such fine musicians were wasting their time with it, Nancy spoke up. She said, for the first, and so far only, time in our twenty-plus years of breakfast jazz listening, “Do we have to listen to this album to the end?” I then realized that it was time to write this column.

Anyone who’s seen me perform knows that I am the first one to appreciate a neglected gem. However, we have long since left behind the 1950s and 1960s. The discographies of the great vintage bands are no longer a secret to Dixieland musicians and haven’t been for decades. Nevertheless, many aging revivalist musicians and revivalist-oriented record producers can’t tear themselves away from the supposed virtues of continued rediscovery. Their obsession with refusing to record anything anyone’s ever heard of is now becoming detrimental to the scene.

A finite number of songs were recorded and written in the twenties. Surely we have no need to “rediscover” every one of them, right down through the fourth-rate Tin Pan Alley hackwork that is now being dredged up in some circles.

A finite number of songs were recorded and written in the twenties. Surely we have no need to “rediscover” every one of them, right down through the fourth-rate Tin Pan Alley hackwork that is now being dredged up in some circles.

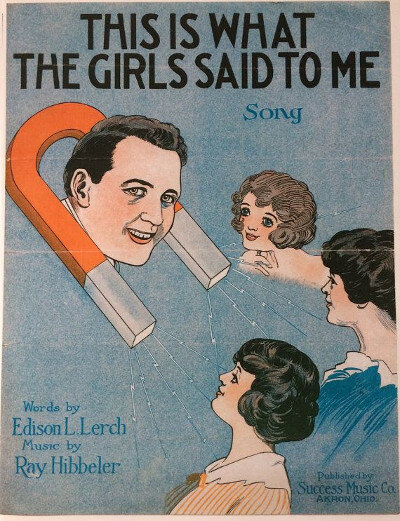

Said another way, after decades of combing old records and sheet music for overlooked treasures, we have bands that are simply choosing, by default, tunes that everyone else has rejected after three or four decades of revivalist research. I doubt that there are many fans on the scene who care to listen to such leftovers.

Moreover, because the opportunities for regular work for full six-or-seven piece bands have constricted substantially in the last three decades, many of today’s recordings are being made by one-time-only studio groups that confront the material for the first time at the recording session. The results often show only too clearly that they are not only struggling to get acclimated to the particular personnel of the day, but also attempting to overcome the additional substantial handicap of doing so while learning the tunes on the fly. From the uninspired readings given with increasing frequency, it is equally obvious that most of the team isn’t particularly turned on by the forgotten pieces that the titular leader has elected to resurrect for the occasion.

Recordings produced this way are not only below par on an absolute scale, they are going the wrong way in terms of today’s vital need to attract new fans to Dixieland. Few enough people outside of our community will buy an album by a nonexistent band that contains no titles which they recognize. Those that do purchase aren’t likely to come back for more once they’ve been subjected to the often plodding interpretations thereon.

As I have said before in this column, the fact that a tune is obscure is very likely to mean that it wasn’t so good in the first place, not that it is an undiscovered masterpiece. This is especially true today with respect to titles waxed in the twenties by jazz artists, nearly all of which have been reissued somewhere since the dawn of the LP era. If one of those ditties hasn’t been picked up by now, it probably doesn’t deserve to be.

Somebody needs to say out loud that, if our journey of rediscovery is not actually over, we are far enough down the road to rest awhile and consolidate our gains. If you look through the catalogue of Stomp Off or G.H.B./Jazzology, just to name our two biggest labels, you’ll find literally hundreds of perfectly good tunes that have been recently revitalized, recorded once or twice, and then abandoned, relapsing back into oblivion to make room for the less meritorious stuff being waxed now.

Somebody needs to say out loud that, if our journey of rediscovery is not actually over, we are far enough down the road to rest awhile and consolidate our gains. If you look through the catalogue of Stomp Off or G.H.B./Jazzology, just to name our two biggest labels, you’ll find literally hundreds of perfectly good tunes that have been recently revitalized, recorded once or twice, and then abandoned, relapsing back into oblivion to make room for the less meritorious stuff being waxed now.

Can’t we concentrate on learning some of those for a while? I’d like to propose a moratorium on revival of unknown selections, and suggest a couple of rules of thumb that ought to lead to improved recordings.

If you have a regular organized band, please plan your albums the way the original revivalists typically did. If you’re going to wax a tune, first put it in your book and play it for a while until everyone is comfortable with it and knows what he/she wants to say about it.

Then, if you record it, tell yourself that you will continue to feature it on your gigs. After all, you found this tune and inflicted it on the rest of us. If you don’t care enough about it to keep it alive, why should the rest of us pay any attention to it?

If your band is going to be a one-shot recording-only team, make sure that at least 75% of the titles you record are ones that will be reasonably familiar to every sideman before he/she gets to the studio. Such a procedure will go a long way to insure that the date will have a satisfactory measure of heat and swing.

If there is a bright spot in all of this, it is that (revivalists will wince at these words) the above-described problems are not especially evident on the Chicago side of the Dixieland scene. Chicagoans, being solo-oriented, have always understood that repertoire, charts and all the other frills mean absolutely nothing when measured against creativity, heat and swing.

A searing version of “When The Saints Go Marching In” has more artistic merit on the jazz scale than a less full-blooded ride on the most complex and obscure work you can name. If you do not agree wholeheartedly with that statement, you do not fully understand what Dixieland jazz is all about and you may unwittingly be contributing to its demise by encouraging the practices criticized above.

Have I beaten these points, some of which I’ve discussed before in this column, to death by now? Maybe so, but we need to wake up and smell the coffee.

Dixieland is going up in flames all around us. It is our turn to put out the fire by recruiting the next generation.

However, too many of us are, unintentionally to be sure, pouring gasoline on the conflagration by perversely refusing to do for today’s audiences the very things that our idols did when we were first exposed to them, the things that drew us to Dixieland decades ago. We have got to stop behaving in this suicidal way, or Dixieland itself will be reduced to ashes.

Want to read ahead? Buy the book!

Want to read ahead? Buy the book!

The full run of “Texas Shout” has been collected into a lavishly illustrated trade paperback entitled Texas Shout: How Dixieland Jazz Works. This book is available @ $20.00 plus $2.95 shipping from Tex Wyndham, On request, Tex will autograph the book and add a personalized note (be sure to tell him to whom the note should be addressed).

Tex Wyndham’s 3 CD Guide to Dixieland with music and commentary is available for $20 plus $2.95 shipping. The separate CD, A History of Ragtime: Tex Wyndham Live At Santa Rosa, is available for $13.00 plus $2.00 shipping. On request, Tex will autograph the inner sleeve and add a personalized note (be sure to tell him to whom the note should be addressed).

Send payment to Tex Wyndham, P.O. Box 831, Mendenhall, PA 19357, Phone (610) 388-6330.

Note: All links, pictures, videos or graphics accompanying the Shouts were added at the discretion of the Syncopated Times editorial staff. They did not accompany the original columns and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of Tex Wyndham.

From roughly 1970-2010, Tex Wyndham was: (1) one of the best-known revivalist Dixieland jazz musicians in the US, as cornetist, pianist and bandleader, (2) one of the best-known ragtime pianists in the US, and (3) one of the most respected critics in the US of Dixieland jazz, ragtime, and related music. He is the only person about whom all three of those statements can be made.