Set forth below are the combined 19th-21st “Texas Shout” columns. This three-part essay appeared in the July, August, and September 1991 issues of the West Coast Rag, (now Syncopated Times).

Set forth below are the combined 19th-21st “Texas Shout” columns. This three-part essay appeared in the July, August, and September 1991 issues of the West Coast Rag, (now Syncopated Times).

A postscript that was included when the Shouts were reprinted in the late 90s will explain why the complete article is not being reprinted now. To discover the omitted portions the reader is encouraged to buy the book.

When I was five years old, Spike Jones and his City Slickers came up with their first big hit record, “Der Fuehrer’s Face.” I loved it, not only the comedy but the musical parts as well.

At that time, as I have written before in these pages, the Dixieland scene was dominated by Chicago-styled bands, which usually use a guitar and string bass in their rhythm sections. While commercial radio was then more broad-based than it is now, and played some Dixieland on occasion, bands with banjo-tuba rhythm sections virtually never appeared thereon.

Spike Jones, of course, made the funniest musical parodies of all time, gems of comedy that stand up beautifully today. His gags, however, were supported by a brand of pseudo-Dixieland that included banjo and tuba. Indeed, when the band wanted to (as airchecks of it prove), the City Slickers could play some formidable two-beat Dixieland.

For that reason, many revivalist fans my age will tell you that Spike Jones’s 78s were key elements in shaping their musical preferences. I collected those platters avidly, listening to them over and over until I knew every note by heart, and then still replaying them.

One day, browsing through one of my local record shops, I stumbled across “Tiger Rag”/”The World Is Waiting For The Sunrise” by The Firehouse Five Plus Two. Hearing it in the audition booth of the store, I felt that a bright light had been turned on. Here was a whole side of just the type of music I’d been responding to all those years, without the distraction of Jones’s jokes (great though his jokes were)! I immediately started acquiring FH5 disks and playing my trombone along with every one as soon as I got home from school each day.

At about this time, I had learned that the music I liked was called “jazz.” I went to the public library and tried to read something about it, to discover how it worked and where to find more of it.

My tastes at that time had been heavily conditioned in favor of the revivalist two-beat sound. I had discovered Turk Murphy (who instantly became my favorite musician) and Lu Watters, but my local stores carried very little of their styles in the racks. There was plenty of Dixieland, but its rhythm sounded too smooth to me and its ensembles too disorganized. I had trouble relating to it. What I was hearing was, of course, Chicago style.

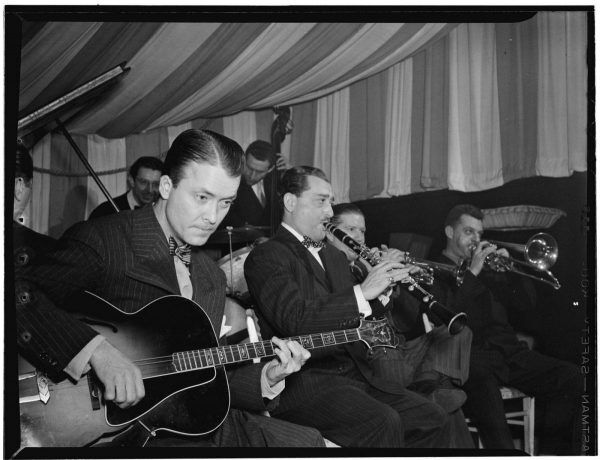

Well, I tried to maintain an open mind and continued reading my way down the jazz shelf in the library, whereupon I ran across some books by a guitarist named Eddie Condon. Condon was a witty and erudite spokesman for older-style jazz, particularly the branch he played which, I later realized, was called Chicago style. I enjoyed his writing so much that I decided to seek out his recordings, hoping that they would be good, not knowing that any intelligently-compiled list of the all-time greatest Chicago sessions will be dominated with dates on which Condon was either the nominal or de facto leader.

Well, I tried to maintain an open mind and continued reading my way down the jazz shelf in the library, whereupon I ran across some books by a guitarist named Eddie Condon. Condon was a witty and erudite spokesman for older-style jazz, particularly the branch he played which, I later realized, was called Chicago style. I enjoyed his writing so much that I decided to seek out his recordings, hoping that they would be good, not knowing that any intelligently-compiled list of the all-time greatest Chicago sessions will be dominated with dates on which Condon was either the nominal or de facto leader.

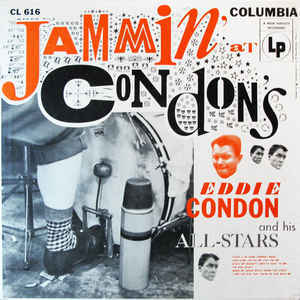

As it happened, I started out with an LP called “Jammin’ At Condon’s” which, in retrospect, turned out to be one of the best Chicago-style albums of its day. Again, that bright light flashed on. Hearing Condon’s incomparable crew of rugged individualists performing at their peaks cut through the problem I’d been having with the sound and approach. I understood what this music was all about, that it was indeed the same Dixieland jazz I’d been enjoying so much. As before, I set out to understand it and to find more of that quality.

At the time of the West Coast and New Orleans revival in the early 1940s, the revivalists were trying to right the imbalance that then existed on the scene in favor of Chicago-style Dixieland. Today, it seems to me, the scales are heavily weighted in the other direction. There are pitifully few high-quality organized Chicago-style bands on the scene, and several misconceptions abound in the Dixieland community about Chicago style.

First of all, I have seen festivals declaring themselves to be “traditional” festivals, when they intend to say to the potential audience not only that they do not hire musicians who play swing and other advanced forms of jazz, but also that they do not hire Chicago-styled combos. This terminology fosters the wholly inaccurate idea that Chicago style is not “traditional.”

To the extent that this point makes any difference to anybody, Chicago style is much more traditional than most of the so-called “traditional” styles prominently featured at “traditional” festivals. The “traditional” festivals regularly hire bands that play (1) uptown New Orleans style, a type of jazz that did not really come to public attention until Bunk Johnson began recording it in the early 1940s, (2) West Coast revival, a branch that originated with Lu Watters in the same early 1940s time frame and (3) British trad, a style that was developed in the 1950s by Ken Colyer, Chris Barber and other English revivalists.

By contrast, Chicago style was on the scene in the twenties, and was thriving before swing (and the changes in jazz that accompanied swing) had ever been thought of. If, by the word “traditional,” you mean authentic Dixieland jazz of the twenties, Chicago has a better claim to be represented than most of the bands usually on the bill at “traditional” weekends.

Second, many fans today don’t truly realize what Chicago style is. They’re so used to hearing banjo-tuba bands that they lump together all guitar-string bass units. I could cite instances where I’ve seen references to “swing” when the context indicated fairly clearly that what was being discussed was Chicago-style Dixieland. It seemed obvious to me that the commentator did not have a clear idea in mind of what constitutes Chicago-style Dixieland and how it differs from swing. Perhaps, therefore, it would be useful to mention some characteristics of Chicago style, together with some thoughts on why such characteristics developed.

Chicago style is, like the other six Dixieland styles I’ve been able to identify, a pre-swing form of jazz. That is, it uses the same musical vocabulary as uptown and downtown New Orleans, West Coast revival, hot dance, etc.

It does not use the thicker chords often heard in swing or other advanced jazz forms, nor does it use many chords that incorporate notes more than an octave above the tonic (i.e., not many 9th chords, no 11th or 13th chords, etc.). Similarly, Chicago jazzmen spend little time exploring the extreme ranges of their horns, in contrast to swing and more advanced jazz musicians, and play less cluttered, less extended lines than jazz players with a post-1930 orientation.

Thus, Chicagoans can, and do, perform from time to time, often as guest artists or sometimes in festival jam bands, with revivalist musicians and everyone gets along just fine. The main difference between Chicago and other styles is in the objectives of the musicians.

All improvised styles of Dixieland require musicians to reach competent levels of ensemble skills and solo skills. However, Chicago style is the only one of the seven styles where solo skills are more highly valued than ensemble skills. Hot dance, as I explained in my “Texas Shout” column in the February 1990 WCR, places its highest values on reading skills. The other five Dixieland styles place their highest values on ensemble skills.

Accordingly, to a Chicago musician, the solo is going to be the focus of the performance. In a typical Chicago format, the combo will play one or two ensemble choruses, and then each musician will take a turn soloing, attempting to find something distinctive, creative and personal to say about the material. Then the band will reassemble for a chorus or two to wrap it up.

The Chicagoans’ solo orientation explains why Chicago bands, by the early 1940s, typically played a fairly circumscribed repertoire of tunes (which, as I have argued in the December 1990 “Texas Shout,” are now unfairly ignored by the revivalist community). Because the rendition is going to center on the solos, during which the melody won’t be heard much anyway, the Chicagoan is just as happy to work with a tried-and-true tune, one with which he feels comfortable. He plans to give you a brand new performance, a different improvisation, a fresh vision of it, from the one he gave you yesterday. He doesn’t see it as repetitive to use that number again today.

Chicagoans prefer to work with the softer-edged guitar and string bass vs. banjo and tuba. Similarly, Chicago pianists often play light single-note treble lines with occasional chordal jabs in the bass.

If you asked a Chicagoan why those things are true, he would probably tell you that he believes the soloist has more freedom in that context. The Chicagoan would go on to say that, if a soloist wishes to construct a line using a few out-of- chord notes, he wants a backup that will still swing hard, but which won’t clash and drag him back into the basic chord the way the more insistent banjo, tuba and two-fisted stride piano will.

Along the same lines, Chicago-style bands, once past the opening ensemble, tend to play with a four-beat rhythm under the soloists. Again, my hypothetical Chicagoan probably believes that the soloist has more freedom that way — that is, he has more room to place his rhythmic accents where he chooses when his support is placing equal rhythmic accents on all four beats of the measure than if he is supported by two-beat jazz (which gives different rhythmic accents to beats one and three than to beats two and four).

I do not want to be in a position of setting up straw men here. Thus, I tested the preceding points with a friend of mine who is a fine Chicago musician. He confirmed that a typical Chicagoan would probably endorse them.

Personally, I would not agree with our hypothetical Chicago jazzman on either one. I do not think that any particular combination of supporting instruments is more conducive to creative soloing than any other, nor do I believe that either two-beat or four-beat rhythm is inherently superior for that purpose.

The most important thing that a soloist’s support can do to inspire good soloing is to be attentive and sensitive to the soloist. In my view, that factor dwarfs everything else you can name. I think most above-average Dixieland soloists would concur. As I see it, this point is, to a large extent, the key to Chicagoans’ aversion to two-beat rhythm and banjo-tuba bands.

Over the past 20-30 years, an increasing proportion of the organized Dixieland bands consists of banjo-tuba groups which strongly emphasize ensembles vs. solos. Further, Dixieland jazz has become a music played principally by hobbyists. Even if they are full-time musicians, most Dixielanders make their livings primarily from something other than playing Dixieland jazz.

Many of the best bands on the circuit, including a lot of my own favorites, are comprised of part-timers. Nevertheless, it is inevitable that the demands of a full-time non-musical (or non-Dixieland) job severely limit the time a hobbyist Dixielander can devote to mastering all the nuances of his music. If he chooses to concentrate the bulk of this limited time on developing ensemble skills, he is likely to be less attuned to the finer points of soloing.

An extensive essay could be written on the current state of soloing among such combos. Suffice it to say for now that these trends, in my opinion, have denigrated creative soloing on so much of the Dixieland scene that we now have quite a few bands out there — including some very popular ones — in which the musicians seem to have only a dim understanding of what a soloist is supposed to be doing with his time.

I suspect that it is the fallout from this unfortunate situation that has caused such deep-seated prejudice among certain Chicagoans against two-beat and banjo- tuba combos. A truly creative soloist is bound to feel hamstrung if he finds himself on stage with bands that are not properly sensitive to a soloist’s needs, particularly if the bandsmen are wielding relatively hard-edged instruments (such as banjo and tuba) or playing forcefully (i.e., two-fisted stride piano vs. right-handed spare jabs).

Part 2

If you’re a festivalgoer, and/or a fan who listens to recordings in your living room, why should you take the trouble to condition your ears to enjoy Chicago style? I can think of several reasons.

You like Dixieland jazz and are spending a lot of your life involved in it. Why not like all of it? After all, Chicago style is Dixieland jazz, and it uses devices that you applaud when your favorite revivalist bands employ them. You should be able to enjoy those licks just as much in the context of a Chicago instrumentation.

Like all styles of Dixieland, Chicago can be, and is, played every way from superbly to atrociously. Why cut yourself off from the chance to hear a top-quality Chicago band at a festival if the only other choices at that particular time slot might be revivalist bands with less promise?

In addition, Chicago bands are almost always single-mindedly aimed at keeping the performances hot and hard-swinging. They are not derailed, as revivalists sometimes are, by a desire to play obscure material without sufficient regard to its potential as a vehicle for cooking jazz, or by a desire to replicate certain figures from vintage recordings without sufficient regard to whether those figures add much to the development of the rides.

Whether they’re played slow or fast, soft or loud, hot performances that swing hard are, essentially, what Dixieland jazz ought to be all about. Chicago goes straight to the heart of the matter much of the time.

In fact, the Chicagoans regularly utilize effects that are aimed at keeping soloists on their toes and goosing the rides along. These devices include chase choruses and backup riffs behind soloists, two very effective heaters-up that are rarely utilized by revivalist bands. If you want to hear how these figures work, you’ll probably need to catch the Chicago band at the festival.

Finally, as mentioned above, the revivalist movement in some quarters has emphasized ensemble playing to such a degree that soloing has been virtually ignored. I hear many revivalist musicians playing solos, and often getting warm applause, who hardly seem to know what the purpose of a solo should be. The current lack of standards for soloists offers little incentive on the revivalist side for a truly creative solo performer, someone who stands out from the crowd in what he is able to do on his instrument and what he wants to say with it, to remain with the revivalist camp.

As a result, the overwhelming majority of the truly outstanding Dixieland soloists today have been driven to Chicago, where their accomplishments are recognized and highly valued. If you want to hear performers who have learned to use their instruments to give you consistently inventive versions of the tunes, you are going to have to spend some time with the all-star Chicago jams.

Many of you know that I’ve been championing the full Dixieland spectrum for years and urging individuals to enjoy more of their favorite music by becoming familiar with all seven branches thereof. In particular, because Chicago style seems on the verge of invisibility at many festivals these days, I’ve tried to point some of you toward it.

From time to time, one of you will report back and say something like “I went to the all-star jam at the festival this weekend, but I simply couldn’t stand all that endless soloing. Moreover, the ensembles were just a mess, with everybody blasting away. I guess this music isn’t really for me.”

I can understand your problem and your frustration. I had that same trouble until, as I mentioned above, I had a chance to hear some 100% undiluted Chicago- style jazz of the highest quality on the “Jammin’ At Condon’s” LP.

Unfortunately, many of the musicians appearing in the contemporary all-star jams are not true Dixielanders at heart. The top-name Dixieland soloists from the twenties who used to man the all-star sessions at Chicago-oriented festivals like the Manassas Jazz Festival are now all dead or inactive. Today’s performers may indeed be all-star jazzmen, extremely capable instrumentalists with enviable reputations on the jazz scene. However, some of them made those reputations playing in big bands, or performing swing or progressive jazz. These musicians, when soloing, have learned how to relate to their accompanying rhythm, and in ensemble have learned, to some extent, how to interact with the pared-down lineups favored by small swing or bop combos. In many cases, however, these artists have not learned the more complex ensemble skills that Dixielanders have—how to listen to as many as seven other improvising musicians playing at once, how to find the right few notes that will enhance and complement their activities, how to avoid moving up or down into the range occupied by another instrument, how to avoid using advanced chords that clash with the group’s harmonic orientation, etc.

These non-Dixieland musicians can’t be blamed, when they’re sent on stage at a Dixieland festival, for playing the kinds of lines that brought them fame in the jazz field. However, it doesn’t take many such players in a jazz band to reduce the proceedings to chaos during ensembles.

Thus, an all-star jam can be an iffy proposition for initiating your contact with Chicago jazz. If you’ve got a Yank Lawson, a Bob Haggart, a Kenny Davern, a Ralph Sutton, you can’t go wrong. These great soloists, and others of their stripe, are also steeped in the Dixieland tradition. Other great soloists, not as well grounded in pre-swing jazz, cannot function as effectively in these types of Dixieland jam sets and can push the whole proceeding out of kilter.

* * * * *

The concluding paragraphs of the foregoing column, and the third installment of the overall essay, will not be reprinted. This material attempted to guide readers toward worthwhile Chicago style by discussing some then-active bands and then-currently-available recordings.

The Dixieland scene has changed significantly during the decade since this article was written. Most of the combos mentioned therein have since disbanded or, in keeping with the substantially reduced audience for Dixieland, made swing a considerably more prominent part of their performances. The majority of the then-surviving veteran soloists, such as Yank Lawson, have passed to their rewards.

At this writing, cornetist Tom Saunders’ Wild Bill Davison Legacy Band, a reunion group not heard all that often, is about the only organized full-sized band that can be depended on to provide nothing but top-drawer unadulterated Chicago style. [ed. note: Tom Saunders himself is now deceased and the legacy band no longer playing.] Thus, in a development that should sadden all true Dixieland fans, Chicago joins white New Orleans and downtown New Orleans as Dixieland styles that are effectively extinct as far as the U.S. organized band scene is concerned.

Most of the recordings discussed in the third installment are out of print (assuming that material by disbanded combos is no longer on the market). Someone seeking good recordings of Chicago style would be well advised to request a free catalog from:

GHB Jazz Foundation

1206 Decatur St.

New Orleans, LA 70116

ph: 504.529.5559 Fax: 504.525.1776

On The Web: Jazzology.com

The Foundation’s various labels, particularly Jazzology (which was founded to preserve Chicago style), contain much top rank Chicago. Especially choice are the eleven multi-CD sets containing all of Eddie Condon’s wonderful series of jam session broadcasts from New York’s Town Hall, collectively featuring just about every great Chicago-style Dixielander of the period performing at peak.

Ed. Note: Part Three spent considerable space on Mosaic’s reissue of the complete Commodore jazz recordings, which contained sessions led by guitarist Eddie Condon that are considered to rank with the best Chicago-style sessions of all time. Those Mosaic sets are no longer in print, but Mosaic has selected choice Condon Commodore sides and combined them with some Condon material from Decca into an 8-CD boxed set that is available on Mosaic’s website.

Back to the Texas Shout Index.

The full run of “Texas Shout” has been collected into a lavishly illustrated trade paperback entitled Texas Shout: How Dixieland Jazz Works. This book is available @ $20.00 plus $2.95 shipping from Tex Wyndham, On request, Tex will autograph the book and add a personalized note (be sure to tell him to whom the note should be addressed).

Tex Wyndham’s 3 CD Guide to Dixieland with music and commentary is available for $20 plus $2.95 shipping. The separate CD, A History of Ragtime: Tex Wyndham Live At Santa Rosa, is available for $13.00 plus $2.00 shipping. On request, Tex will autograph the inner sleeve and add a personalized note (be sure to tell him to whom the note should be addressed).

Send payment to Tex Wyndham, P.O. Box 831, Mendenhall, PA 19357, Phone (610) 388-6330.

Note: All links, pictures, videos or graphics accompanying the Shouts were added at the discretion of the Syncopated Times editorial staff. They did not accompany the original columns and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of Tex Wyndham.

From roughly 1970-2010, Tex Wyndham was: (1) one of the best-known revivalist Dixieland jazz musicians in the US, as cornetist, pianist and bandleader, (2) one of the best-known ragtime pianists in the US, and (3) one of the most respected critics in the US of Dixieland jazz, ragtime, and related music. He is the only person about whom all three of those statements can be made.