Chris Barber died on March 2nd, 2021. Find our obituary here: British Trad Jazz Pioneer Chris Barber has Died

Strange as it seems, there was a time when it was not unusual for trad jazz recordings to be on the pop charts in Great Britain. Such recordings as Kenny Ball’s “Midnight In Moscow” (which also made an impact in the U.S.), Acker Bilk’s “Stranger On The Shore” (an easy-listening feature for his clarinet with strings), Humphrey Lyttelton’s “Bad Penny Blues,” and Chris Barber’s version of Sidney Bechet’s “Petite Fleur” (which sold over one million copies and made it to #3 on the U.K. Singles Charts) were well known.

Starting with George Webb’s Dixielanders in the mid-1940s and picking up steam throughout the 1950s, trad jazz was embraced by many young listeners and amateur musicians in addition to the pros. In a bizarre but significant British movie, It’s Trad, Dad, the fictional story (which has many appearances by top British bands) portrays the Dixieland-oriented music as anti-establishment, sort of like rock and roll was depicted in the U.S., and blamed for loosening the morals of young people, resulting in potential riots! The trad movement lasted until 1963 when the rise of the Beatles and other rock groups forced it back underground.

Of all of the major bandleaders who were active during that era, only trombonist Chris Barber is still on the scene today. An open-minded player who has stretched his group’s music to include a variety of blues, r&b, and mainstream swing in addition to New Orleans jazz, Barber has been an important bandleader since at least 1954.

Chris Barber was born as Donald Christopher Barber on April 17, 1930, in Welwyn Garden City, Hertfordshire, England. He started playing violin when he was seven, primarily playing classical music. Barber originally planned to become an actuary and was always skilled at mathematics but, after becoming interested in traditional jazz, he bought his first trombone in 1948 when he was 18. Barber developed very quickly and in 1949 he worked with Beryl Bryden’s Backroom Boys, briefly with clarinetist Cy Laurie, and formed his first band. On October 11, 1949, 69 years ago, he made his recording debut, leading a sextet through four classic jazz songs from the 1920s. It was a rather fast start for the young trombonist.

Barber worked with Reg Rigden’s Original Dixielanders for a time during 1949-50 and led another privately issued record session. Although already a fine musician, he worked on his skills by studying trombone and string bass at the Guildhall School of Music during 1951-54. Barber headed a few Dixieland-oriented dates for the Esquire and Tempo labels in 1951 and recorded four songs with a Danish trad band in Copenhagen in 1952. Later that year, he formed a quintet that included clarinetist Monty Sunshine and banjoist-singer Lonnie Donegan, both of whom would become major names in the near future. With Pat Halcox on trumpet, they performed in London during December 1952 and the following January. However Halcox was not ready to give up his job as a research chemist to become a full-time musician, so he turned down the chance to officially join the band.

Chris Barber had heard of Ken Colyer, a British cornetist who was so in love with New Orleans jazz that, during his visit to the U.S., he had overstayed his visa to play in New Orleans and been arrested. When Barber heard that he would soon be deported back to England after spending a short time in the local prison, he not only offered him a job with the band but the opportunity to be its leader.

The arrangement lasted for 14 months. The pianoless group (with Colyer, Barber, Sunshine, Donegan, Jim Bray on bass and tuba, and drummer Ron Bowden) started to become quite popular in the British trad world but there was a problem. Colyer wanted their music to be ensemble-oriented New Orleans jazz in the tradition of Bunk Johnson and George Lewis. Barber preferred that the music be polished and have much more variety, ranging from 1920s classics and the New Orleans jazz that Colyer preferred to more recent material. Their arguments eventually tore the group apart. Each of the musicians gave Colyer their two weeks’ notice and Barber was appointed the new leader. Pat Halcox, who had finally decided on music for his career, became the band’s trumpeter. While Barber and Colyer would later make peace and have a few recorded reunions, they went their separate successful ways.

1954 was the breakthrough year for Chris Barber. Not only did he have his own increasingly successful band and start recording for the Decca label, but he met Ottilie Patterson (1932-2011). Originally a classical pianist and a soft-spoken art major from Northern Ireland, she had fallen in love with early jazz, particularly the recordings of Bessie Smith. Patterson had a powerful voice and sounded very much like an African-American blues singer from the 1920s; audiences were always surprised the first time they saw her. She had enjoyed the music of the Ken Colyer/Chris Barber Band and, after sitting in with Barber’s group in the summer of 1954, she was quickly hired. Ottilie Patterson was a major attraction with the group during 1955-62, recorded both with Barber and as a leader, and was married to the trombonist during 1959-83. Health problems resulted in her singing less often starting in 1963 although she appeared with the trombonist on an occasional basis up until 1983.

Another major event for Barber in 1954 was the recording by banjoist Lonnie Donegan (1931-2002) of the huge hit “Rock Island Line.” Donegan, who originally played guitar, was born Tony Donegan but changed his first name to Lonnie after Lonnie Johnson. With Colyer’s encouragement the previous year, Donegan began singing a British version of folk music and blues that would soon be dubbed “skiffle.” He performed with a trio from the band as a change of pace during their performances, a practice that Barber continued when he took over the group. When “Rock Island Line” (which has Barber playing bass) and its B-side “John Henry” were released in 1956, they sold a million copies in the U.K. and made the top ten in the United States, starting a skiffle craze. Donegan soon left Barber’s band and had a prosperous career of his own, having 31 hits in all. His style was influential and inspired John Lennon to form the Quarrymen with Paul McCartney in 1957. Donegan and Barber remained friends and participated in reunions as late as 1998.

Chris Barber was fortunate to have very stable personnel during most of his career although his rhythm section underwent some changes as the group became more and more famous. Micky Ashman became the band’s bassist in mid-1955 and was succeeded by Dick Smith the following year. When Donegan was on his way to becoming a major name, he departed in April 1956 and was succeeded at first by Dickie Bishop and then for a long time by Eddie Smith. Graham Burbidge took over on drums in 1957.

Monty Sunshine (1928-2010) was an important member of Barber’s band until 1960. His fluent clarinet solos fit perfectly in the ensembles and he had his own sound. In 1956 Sunshine recorded a version of Sidney Bechet’s “Petite Fleur” that, when it was released in 1959, became such a major hit that he formed his own band the following year; Ian Wheeler became Barber’s new clarinetist. As was true of Donegan and Colyer, Sunshine participated in several Barber reunions during his later years before his retirement in 2001.

Unlike most of the other British trad bands of the era, Chris Barber’s was open to accompanying American guests on their European tours, including those from the blues world, a situation that delighted Ottilie Patterson. Among those who were featured on recordings with Barber’s group were such greats as Sister Rosetta Tharpe (1957), Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee (1958), Champion Jack Dupree (1959), James Cotton (1961), clarinetist Edmond Hall (1962), Louis Jordan (1962), gospel singer Alex Bradford (1963), Sonny Boy Williamson (1964), Jimmy Witherspoon (1964), Howlin’ Wolf (1964), Albert Nicholas (1968), Ray Nance (1974), Russell Procope and Wild Bill Davis (1976), Trummy Young (1978), Muddy Waters (1979), and Dr. John (several times in the 1980s). The flexible band adapted themselves to each of their guest’s repertoire and also gave them a New Orleans jazz setting that cast fresh light on their music.

With the success of “Petite Fleur,” the Barber band visited the United States on a fairly regular basis starting in 1959 when they appeared at the Monterey Jazz Festival. The following year their American tour included New Orleans where they recorded an album apiece with Billie and DeDe Pierce, and Sidney DeParis and Edmond Hall.

The first half of the 1960s was a particularly busy time for Chris Barber with constant performances, recordings and tours. His band (with Halcox, Wheeler, Smith, Smith, and Burbridge) had no personnel changes at all for four years until mid-1964 when electric guitarist John Slaughter made the group a septet. His playing, which crossed over into rock and electric blues, did not always please Barber’s veteran fans but Slaughter became a long-time member of the ensemble as the group’s music continued to expand and sought to remain relevant after the trad boom ended. Stu Morrison, who took over for Eddie Smith later in 1964, primarily played banjo which worked well as a contrast with Slaughter.

Other key members of what became known as the Chris Barber Jazz & Blues Band were clarinetist-altoist John Crocker (starting in 1968), banjoists Johnny McCallum (who debuted with Barber in 1973) and Paul Sealey, guitarist Roger Hill, bassists Jackie Flavelle (who often played electric bass in the 1970s) and Vic Pitt, and drummers Pete York (after Burbridge ended his 19-year stint in 1976), Norman Emberson, Russell Gilbrook and Alan “Sticky” Wickett. Ian Wheeler returned in the late 1970s to give the group a second reed next to Crocker, a place later filled by John Defferary. Through it all, a constant was trumpeter Pat Halcox (1930-2013). For 54 years, an association that topped Harry Carney’s 49 years with Duke Ellington and Freddie Green’s 50 years (with a one year “vacation”) with Count Basie, Halcox contributed a melodic lead, lyrical solos and consistently satisfying improvisations to Barber’s groups. He spent virtually his entire career with Barber, retiring in 2008.

Barber debuted a new unit in 2001, the Big Chris Barber Band. This group, which is still active and has been Barber’s main band ever since, is 10 or 11 pieces with two trumpets, two trombonists, three reeds, one or two guitarists, bass and drums. The music is more swing than New Orleans-oriented but still retains Barber’s roots in early jazz.

Fortunately most of his recordings from the early days have been compiled and reissued by the Lake label (www.fellside.com) including ones titled The Complete Decca Sessions 1954/55, 1955, 1956, 1957-58, 1959-60, and 1961-62; all are two-CD sets except 1955. Many of Ottilie Patterson’s main recordings with Barber are available on the single discs That Patterson Girl and Blues Book And Beyond.

While the 88-year old trombonist has naturally slowed down during the past decade, he still appears fairly regularly in England and happily is being celebrated while he is still with us. Chris Barber’s impressive musical legacy should be explored by any listener interested in classic jazz.

Reviews of currently available Chris Barber albums.

Chris Barber’s Jazz Band in Detroit

Chris Barber has been a major part of the British trad scene for over 70 years. While he recorded studio sides as a leader as early

Chris Barber: Back In Berlin 1960

Chris Barber has had a remarkably long career. The 86-year old British trombonist first led a trad band in 1953, one that was co-led by

Chris Barber & The Clarinet Kings

British bandleader-trombonist Chris Barber was very fortunate to have two great clarinetists in his band for extended periods: Monty Sunshine (1953-60) and Ian Wheeler (1961-68).

Chris Barber Goin’ To Town In Carlisle ’94

Trombonist Chris Barber formed his first band in 1949 and retired in August 2019. The Big Chris Barber Band will carry on, and continue to

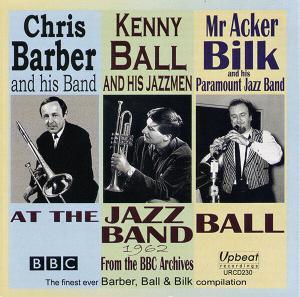

Barber, Ball and Bilk: At The Jazz Band Ball

Three of the greatest and most popular British trad jazz bands were led by trombonist Chris Barber, trumpeter Kenny Ball, and clarinetist Acker Bilk. Each

Chris Barber: Back In Copenhagen 1961

British trombonist-bandleader Chris Barber, who recently turned 90, retired from playing last year after a 70-year career. But even though he has stopped performing, it

Chris Barber at the BBC, with Special Guest Joe Harriott

This concert for the BBC Jazz Club program opens with what to Chris Barber fans will be the familiar signature tune of the band, “I

Chris Barber’s Jazz Band & Ottilie Patterson • The Allan Gilmour Tapes

While Paul Adams and the Lake label have been slowing down a bit in recent times, whenever he runs across a valuable and previously unheard

Chris Barber • Back in Copenhagen 1961

Aged 90 and now retired from playing, Chris Barber is an institution in the annals of British traditional jazz, having been on the scene since

A Jazz Club Session with Chris Barber’s Jazz Band

Since Chris Barber has retired from playing, one might expect that there would be no more “new” Barber CDs forthcoming, but that would be a

Since 1975 Scott Yanow has been a regular reviewer of albums in many jazz styles. He has written for many jazz and arts magazines, including JazzTimes, Jazziz, Down Beat, Cadence, CODA, and the Los Angeles Jazz Scene, and was the jazz editor for Record Review. He has written an in-depth biography on Dizzy Gillespie for AllMusic.com. He has authored 11 books on jazz, over 900 liner notes for CDs and over 20,000 reviews of jazz recordings.

Yanow was a contributor to and co-editor of the third edition of the All Music Guide to Jazz. He continues to write for Downbeat, Jazziz, the Los Angeles Jazz Scene, the Jazz Rag, the New York City Jazz Record and other publications.