An Enlightened Jazz Era

The Berkshires of Western Massachusetts with its historic landmarks, museums, and performing arts venues have long been a vacation mecca for tourists, and New Yorkers in particular, especially those seeking cultural entertainment. In the years immediately following World War II, it was an easy two-and-a-half hour drive from Manhattan on the Taconic State Parkway to any of the quaint New England towns that had long attracted summer visitors.

The Boston Symphony Orchestra had established its summer home at Tanglewood in Lenox. Ted Shawn’s dance entourage held forth at Jacob’s Pillow in Becket, and there were summer theater companies in Stockbridge and Williamstown.

The Barbers

In 1950, a young couple from New York, Philip and Stephanie Barber purchased a portion of the summer estate of the late Countess de Heredia, property that straddled the towns of Stockbridge and Lenox, and converted one of the buildings into an inn. Their plan was to recreate a cultural environment in this pastoral setting for the kind of company, conversation, and conviviality that they had come to treasure back in metropolitan New York.

On a July evening in 1950, the Barbers opened the doors of the renovated farm buildings they had named Music Inn and invited Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, Alan Lomax, and Rev. Gary Davis to perform in what had been a carriage house for an audience of 50 people who were the first guests at the Inn. Things became a bit chaotic later in the evening when the Inn’s ancient water pipes ceased to function, and the Barbers had to send their guests to their rooms with bottles of ginger ale to flush the toilets.

Folk & Jazz Roundtable

Among the early guests was Marshall Stearns, an English professor at Hunter College in New York City and a noted jazz historian and critic. At the urging of the Barbers, he organized The Folk and Jazz Roundtable, considered one of the first serious inquiries into the origins and development of jazz. Langston Hughes read poetry and introduced Mahalia Jackson to the Barbers, which led to the gospel singer’s first performance for a white audience outside of her church.

A unique aspect of these gatherings was that the musicians who were invited to perform at the Inn participated in the discussions. Critic Nat Hentoff remembered the time Charles Mingus exclaimed, “Hey, I’ve got roots!” after hearing a ragtime solo by pianist Willie “The Lion” Smith. When Dr. Willis James, an authority on field hollers, demonstrated a field holler in five-four time, Dave Brubeck was convinced his quartet was on the right track in playing their complicated time signatures.

Berkshire Music Barn

Berkshire Music Barn

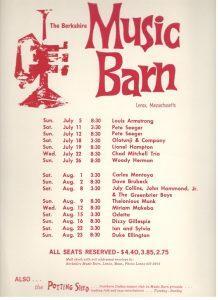

The popularity of the Roundtables increased to such an extent that in 1955, the Barbers remodeled what had been a hay barn on the estate into a 600-seat auditorium to house a summer-long series of jazz and folk concerts. As the Berkshire Music Barn, it was one of the first venues devoted solely for the presentation of jazz and folk music. The 1955 lineup included the likes of Coleman Hawkins, Jimmy Rushing, Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry, Thelonious Monk, Carlos Montoya, Mary Lou Williams, Gene Krupa, Eddie Condon, and the Wayfarers.

Over the next decade the Barn hosted the leading artists of the period, including Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, the Weavers, Miriam Makeba, and Odetta. The Modern Jazz Quartet became a group in-residence, and Atlantic Records recorded them with Sonny Rollins on the Barn stage. Dave Brubeck and his family spent an entire summer living in guest rooms on the property. In 1956, 24 musicians joined in a jam session recorded by the Voice of America as the “Historic Jazz Concert at Music Inn.”

Lenox School of Jazz (1957-60)

Another development that came out of the Roundtable discussions was the establishment of the Lenox School of Jazz in 1957. With John Lewis of the Modern Jazz Quartet as artistic director, four three-week sessions were held on the Music Inn grounds over the next four summers. Musicians who served on the faculty during that period included Ray Brown, Herb Ellis, Dizzy Gillespie, Oscar Peterson, Bob Brookmeyer, Connie Kay, Percy Heath, Jimmy Giuffre, Max Roach, J.J. Johnson, as well as Marshall Stearns and Gunther Schuller.

Recognized internationally, the School accepted 155 students from 20 states and from as far away as Africa, Brazil and India. As John Lewis commented, “The School of Jazz was a groundbreaking experiment, and although it lasted only a short time, its impact was felt far beyond the confines of Music Inn.” The School inspired the introduction of jazz studies at major universities and conservatories, and hastened the collapse of the artistic and social barriers between the classical world and the world of jazz. The integration of related disciplines —composition, theory, improvisation and history—into a single course of study provided the model for future jazz instruction.

In 1957, the Barbers bought and moved into Wheatleigh, the main house of the original estate and began converting it into a palatial inn. After a few years, they found that running the two places was more than they cared to handle, and they decided to sell the Music Inn and Berkshire Music Barn.

The Soviero Years (1960-67)

The new owner was Donald Soviero, a New York lawyer by training, who had been operating a ski resort in the area where he introduced snowmaking to the Berkshires. He had also been a partner in a New York City booking agency that numbered Ray Charles among its clients. A story circulated that Charles wanted to buy Music Inn and convert it into a drug and alcohol rehabilitation center for musicians. But the deal fell through due to a personal quarrel between the two principals.

With Soveiro in charge, he expanded the concert attendance capacity out onto the lawn to accommodate audiences of 5-6,000. Seating in the Barn was on wooden folding chairs and in bleachers, with the overflow scattered outside on blankets and lawn chairs. The “Green Room” where the artists relaxed before performing was a rather stark, dimly-lit facility with a dirt floor. It was all quite casual.

Many of the same performers from the 1950s continued to play at the Music Barn in the 1960s. A then-unknown folksinger named Bob Dylan was introduced by Joan Baez at a concert in the early ’60s. The Potting Shed, a cocktail lounge the Barbers had opened in 1957, became a fancy Northern Italian restaurant with entertainment by Randy Weston, Josh White, the Simon Sisters, and a pre-“American Pie” Don McLean on the musical menu.

My Indoctrination

I cut my teeth as a jazz journalist the three years I was publicist for the Berkshire Music Barn and Potting Shed. I was operating a small advertising/ public relations agency in Springfield, Mass. when a phone call summoned me to the Berkshires to meet one of the most flamboyant and unpredictable people I had ever met—much less work for.

Since my job was to provide advance publicity for the weekend concerts, my interviews of the artists were usually brief and impromptu, but in looking back, provided a wonderful and very broad introduction to jazz and folk music. Imagine having close-up contact and conversations with Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Dave Brubeck, Stan Getz, Pete Seeger, Odetta, Joan Baez, Judy Collins, and Peter, Paul, and Mary.

Recollections

I would occasionally record an interview with a touring artist for a local radio station. My first contact with Louis Armstrong left me unimpressed. I apparently caught him when he was tired and out of sorts, for he was most uncommunicative. However, once he got on stage, the Armstrong grin and charismatic personality came to the fore. The next year when I saw him, he could not have been more outgoing and cordial when we had an in-depth discussion about Swiss Kriss, his laxative of choice.

Duke Ellington did not travel on the band bus and would arrive in a Cadillac or Lincoln town car driven by the band’s “straw boss,” saxophonist Harry Carney. One year, Duke was ill, so we had Cab Calloway fronting the band and Billy Strayhorn on piano. Erroll Garner’s manager would call me almost daily for two weeks prior to his concert to inquire about the status of ticket sales. Apparently we filled the house because Erroll sent a vase to my wife as a token of his appreciation.

I found Stan Kenton to be the most cordial and cooperative of the visiting bandleaders, and we engaged in an interesting conversation as to what type of music was played on the bus sound system while traveling. (It was a bit of everything.) I asked Count Basie if he had any idea of how many times the band had played its theme, “One O’Clock Jump.” (He had no idea.) On another occasion, Carlos Montoya took great delight in showing my 10-year-old son how to play the flamenco guitar.

As time went by, it became obvious that Soviero may have been an adroit promoter, but he was not a good businessman. In the fall of 1967, he declared bankruptcy and walked away from the place. His last known sighting was in Hong Kong.

Times Were Changing

By 1970, new owners opened shops and a movie theater on the property and promoted live musicin a hillside amphitheater by such performers as Van Morrison, Bruce Springsteen, Tina Turner, and the Kinks, with the thought of creating a “Woodstock in the Berkshires.” But the concert scene and audience had changed. As the size and noise of the crowds grew, complaints from town officials and neighbors increased. Crowds would gather hours, even days before the concerts, and the two-lane New England roads were not equipped to handle the volume of traffic generated by concerts attended by up to 15,000 frenzied fans.

Matters came to a head at an Allman Brothers concert in 1979 when concertgoers charged the gates and battled security forces, and the curtain finally came down. By the mid-1980s, the grounds had been transformed into a condominium complex with little other than a single building that was once the Potting Shed Restaurant to recall the glory days of the Music Inn, the Lenox School of Jazz, and the Berkshire Music Barn.

Lew Shaw started writing about music as the publicist for the famous Berkshire Music Barn in the 1960s. He joined the West Coast Rag in 1989 and has been a guiding light to this paper through the two name changes since then as we grew to become The Syncopated Times. 47 of his profiles of today's top musicians are collected in Jazz Beat: Notes on Classic Jazz.Volume two, Jazz Beat Encore: More Notes on Classic Jazz contains 43 more! Lew taps his extensive network of connections and friends throughout the traditional jazz world to bring us his Jazz Jottings column every month.