Peggy Lee (nee Norma Deloris Egstrom) was one of the vocalists who made their mark with big bands in the 1940s. Some of these included Helen Forrest (whom Lee replaced in Benny Goodman’s band), Helen O’Connell, Helen Ward, Doris Day and on the male side, Frank Sinatra, Billy Eckstine, Ray Eberle.

Peggy Lee (nee Norma Deloris Egstrom) was one of the vocalists who made their mark with big bands in the 1940s. Some of these included Helen Forrest (whom Lee replaced in Benny Goodman’s band), Helen O’Connell, Helen Ward, Doris Day and on the male side, Frank Sinatra, Billy Eckstine, Ray Eberle.

Lee’s career was lengthy—from her start with Goodman through the 1990’s and includes many highlights: a number of hit songs in the ’40s, a classic album Black Coffee in the ’50s, roles in several films, including an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress in Pete Kelly’s Blues (1955), a hit song, “Fever” (1958) and a final hit with “Is That All There Is” (1969). She wrote about 200 songs and started a company called Peggy Lee Enterprises, which includes music publishing firms and a production unit for television and films.

Lee grew up in 1930s North Dakota and hooked into the popular music of the day on the radio-Goodman, Dorsey, James, Basie. She recognized her own talent and saw her musicality as a way out. She sang on local radio and played area gigs until being brought up to the big time by Benny Goodman in 1941.

Musically, Peggy Lee was slightly less talented than some female vocalists of the era and slightly more talented than others, with less dynamic range and a lighter voice-more likely to convincingly coo than to growl. Critics have likened her to Billie Holiday and there is sometimes a similar light and slightly girlish quality to their voices, but overall, Holiday was more of a risk taker. Peggy Lee was singular, though, with an instantly recognizable voice, rhythmic flexibility and the ability to win over an audience and gain the respect of musicians.

I believe Lee is most effective when she is not trying too hard and approaches a song with almost a throwaway naturalness. “Just in Time” in the Ultimate Peggy Lee collection works because of that. There is an effort to “sell” the song, but there’s an archness to it that draws attention to itself. “I know you’re watching me and I’m watching you watch me.” It marks the kind of bond that she sometimes locks into with the listener. However, when she tries to get into the blues or Rhythm & Blues—there’s a lack of grittiness. She did have an early hit with “Why Don’t You Do Right,” which is in this collection, but despite the earthiness of the song, she plays the lyric as a fed-up-yet-wistful mistress and the message becomes more yearning and less waspish.

Her 1953 album (with more tracks recorded in 1955) Black Coffee was an early “theme” record, exploring the fragility of love. Since the 1940s, Lee’s personal life had become rocky. She was able to attack a song like “Black Coffee” and make it fit like a glove. It’s not a blues, but Pete Candoli’s muted trumpet and sparse Lou Levy piano give it a properly forlorn bluesy quality.

She wrote several songs in 1955 for Lady And The Tramp including “We are Siamese.” It’s catchy, but it must have also served to introduce 1950s American children to the cheesy approach followed by generations of composers scoring TV or films set in the “Orient”: pentatonic riffs with slight permutations (here she doubles down by harmonizing with herself in open fifths) in everything from “Charlie Chan,” “Mr. Moto,” “Fu Manchu,” and “I Spy” episodes in Hong Kong.

The next big song for Lee, in 1957, was “Fever.” She was asserting more and more control over her career and began to purvey an image of sophisticated, elusive glamour. Her voice grew huskier, but any seductiveness still seems filtered, in contrast to the more overt sexuality of singers like Julie London or June Christy. She takes credit for the arrangement of “Fever”—just bass, a little percussion, and finger snaps. In fact, there are finger snaps on the original by Little Willie John, but in any case, there’s a lot of space in the recording and more than 60 years later, it still works.

In the 1950s, most popular singers, Lee included, had Latin and Brazilian material in their repertoire. She fits well into the Bossa Nova context, as here on “Sweet Happy Life.” “(You Gotta have) Heart” done as a mambo is not exactly in her wheelhouse but is worthy enough to throw on the turntable if you want to roll up the rug and cha-cha in the living room. “Too Close for Comfort” is the kind of swinging suburban tune you could put on the turntable after the cha-cha if you want to switch to a coy fox trot.

“You Deserve,” is a throwaway with a descending bass line that opens up ample space for the Lee purr. “Big Spender” is a natural, although the arrangement here is a little hyperbolic. In “World on a String,” she does a nice job of varying her rhythmic approach. “I’m a Woman” is not convincing. She doesn’t do gutsy very well. “It’s a Good Day” is a nice piece for Lee. She ditches the darkness and gets down to the program of pitching a rosy American positivity: “Take a deep breath and throw away the pills.”

“The Folks Who Live on the Hill” is another foray into nostalgic Americana and I admit not caring for very much for this tune. There’s an appropriate emotional quaver in Lee’s voice as she sketches out a scenario of future rural bliss; moving into what I imagine would actually be the factory owner’s big house, located up on the hill so he could keep a close eye on his investment. Unfortunately, the arrangement brings out the bathos lurking in the song.

The track “Try a Little Tenderness” was apparently unreleased when it was recorded in 1963. Written in 1932, it was given a new life in Otis Redding’s impassioned 1966 version. This was a good choice for Lee; an old song, crafted in the old style. Lee touches lightly on each word in the verse, like skipping stones across a pond, then she digs in a bit in the bridge.

Lee worked consistently, but did go through periods of relative obscurity. As with Frank Sinatra, she made some ill-fated efforts during the rise of Rock to regain popular traction, but several times, she was able to hone her identity, find the right material and re-emerge. In 1965, Sinatra hit with “When I was Seventeen” and in 1968 “Is That All There is” worked for Lee, making it to #1 on the Adult Contemporary charts. Jerry Lieber and Mike Stoller, more noted for their many rock and roll and R&B songs, wrote “Is That All There is.”

For those who don’t know the song, it’s in the world-weary cabaret style of Kurt Weill and Jacques Brel. The lesson is: life stinks, so we might as well have a drink. This is “Black Coffee” taken to its logical conclusion. The song arrived at a point when Lee’s public persona had been solidified as the classy lady who’s seen it all and seldom leaves her penthouse and her poodles. The decadence limned by the arrangement and fleshed out in her world-weary performance stood out starkly in the cultural frenzy of 1968. This too, stands up well in the passage of time.

Although Lee recorded until 1993 and continued to perform, this was her last hit. The sound of Lee’s voice is almost the opposite of “tough as nails,” but that’s what she had to be in order to make her career work as well and as long as she did. She set the table for the female power shift that we saw with Madonna in the 1980s and which continues though Lady Gaga, Beyonce, and others. Lee herself acknowledged the limitations of her voice, but she understood how to communicate a lyric with musicality and an individual style, with material that ranged from novelty, mainstream, exotic, and introspective ballads. You can find all these represented on the Ultimate Peggy Lee collection.

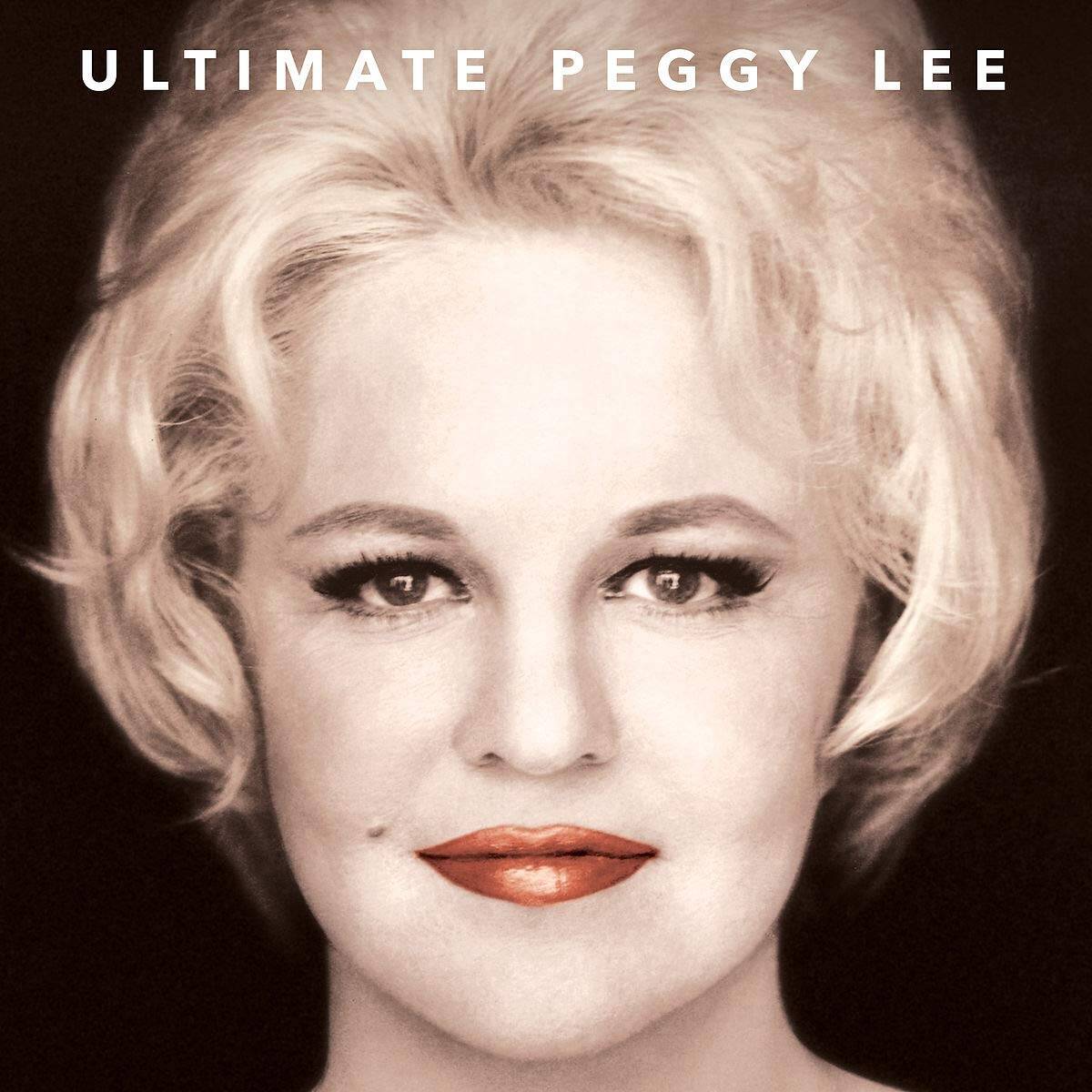

Ultimate Peggy Lee

Capitol Records (www.umgcatalog.com)

Steve Provizer is a brass player, arranger and writer. He has written about jazz for a number of print and online publications and has blogged for a number of years at: brilliantcornersabostonjazzblog.blogspot.com. He is also a proud member of the Screen Actors Guild.