When I started pursuing the legendary scrapbook that once belonged to Fred Hager, one of the aspects of this ultimate treasure was a steamer trunk full of ephemera. For years I heard about it potentially existing, containing perhaps all the secrets of the acoustic recording era we have all wanted to know. Not until I started to communicate with Fred Hager’s great-nephew did I finally learn of the trunk’s existence, and even more recently got to handle its remaining contents. Nothing was quite as exciting as finally putting together the pieces of this puzzle. Even with this, there is still more to find. Nothing in this trunk was junk.

Way back in 2012 I first learned of a big dump of Fred Hager’s papers on various auction sites. Around that time, the direct descendants of Fred sold off large portions of what was left of his papers. According to Jim Walsh, and Hager’s own words, there was once a massive collection within the Hager family, and a majority of it belonged to Fred. There were thousands of records, catalogs, periodicals, books, sheet music, stock arrangements, and anything else that could be thought of by a passionate collector. Toward the end of his life, Hager realized that there were some collectors who wanted to preserve the earliest history of recorded sound, this including the contributions of Hager. Meeting these younger collectors in the 1940s and ’50s, this inspired Hager to start giving pieces away. This new found passion brought so much joy and inspiration to old Hager. Jim Walsh said in a 1950 article that:

I believe the first artist to arrive was Fred Hager…Fred had brought with him a batch of rare record catalogs that made my mouth water, as well as a dubbing of the first disc made for the Columbia company — a band record which Fred himself conducted.

This was part of an article Walsh wrote in the December, 1950 issue of Hobbies, recounting a large reunion of old recording stars hosted in Freeport earlier in the summer. This event was famously filmed, although silently, but can be viewed online, and is currently preserved by the Library of Congress.

It was stated in several other articles by Walsh that Hager had a massive and important collection, by Walsh’s own account, and Hager’s to-be-expected brags. Even with all this hype, little of what was actually in this collection was discussed, and after Hager died in 1958, things got split up. All three of Fred’s siblings were still living at the time, so it seemed that pieces were scattered within the homes of Jimmy, and sister Georgiana. However, when Jimmy died in 1961, much of the larger pieces were gone. Jimmy unfortunately had Alzheimer’s in the last few years of his life, and he told the family to sell off all of the pieces he had collected over the years. According to Jimmy’s grandson, there was once a basement full of drum equipment and trunks full of ephemera. Likely many pieces that once belonged to brother Fred were sold with the rest.

Fast forward to the auctions of the last decade or so. At the end of 2019, I acquired some of Hager’s papers from a collector in Alabama, after a year of attempting to make a deal. Within these papers was a single decrepit scrapbook, some newspaper clippings, and a few bound screenplays and media pitches by Hager and Justin Ring. We still have yet to put all the pieces together on what happened to the supposed trunk between Jimmy’s death and the last decade. Only in the last year was the actual trunk recovered. When I first started communicating with Fred Hager’s great-nephew, he told me of a legendary large steamer trunk that was once filled with records and sheet music. After over a year of communicating, and two visits, he was excited to tell me that the trunk of his youth was found. He and two other family members moved the supposedly massive trunk back into his house, where it had once been decades ago (note that I have not yet seen it in person). He was kind enough to transfer much of what was left inside to a more compact and less ragged box for preservation.

So on my last trip to New York, I got to see some of the material. Not at all did I expect to see this stuff on this trip. It was a spontaneous decision of Hager’s nephew to bring along the box of papers. A few friends and I took a tour of the Louis Armstrong House Museum, under the supervision of Ricky Riccardi, and on the way to the house, Don (Hager’s nephew) called me to tell me that he decided to bring along some pieces from the trunk. You could imagine my shock and excitement at that moment. After the tour, everyone regrouped and we met with Don. Due to the spontaneity of the situation, physically going through the box was quite an affair. While we were driving around Queens (two in front and three of us crammed in the back), and as the sun was setting, I manically combed through the historic papers. We were all trying to decide on where to eat dinner at this point.

One of the most off-putting things to note is that one of the first things I saw after opening it up was a few small newspaper clippings about Elvis. Yes, that’s right, Elvis. The rest of what was in there made more sense with the context. It was one handwritten manuscript after another, elegantly tagged with the loving initials JR.

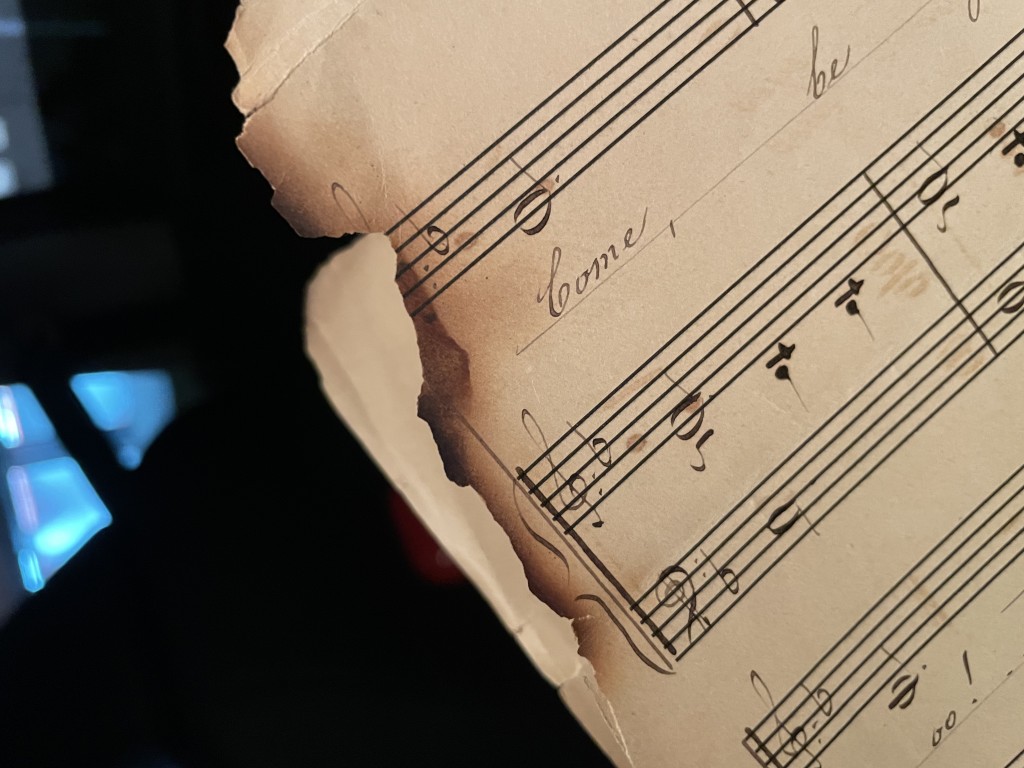

For years I had wondered if any of Justin Ring’s famous arrangements had survived, and it seems that we now know where many of them have remained. These pages were certainly older than the 1920s, as they are the size of typical large format sheets of the time. They were exquisitely penned, with each line and note clear as could be. A far cry from the supposedly difficult-to-read arrangements that Arthur Pryor handed to his and Sousa’s bands. Many of these pieces were actually quite unfamiliar, one of them being called “Kangaroo Jiggers,” one that may not have been published. Another few were pieces by Hager, one being from his “Wildflower suite,” which was recorded around 1915.

For years I had wondered if any of Justin Ring’s famous arrangements had survived, and it seems that we now know where many of them have remained. These pages were certainly older than the 1920s, as they are the size of typical large format sheets of the time. They were exquisitely penned, with each line and note clear as could be. A far cry from the supposedly difficult-to-read arrangements that Arthur Pryor handed to his and Sousa’s bands. Many of these pieces were actually quite unfamiliar, one of them being called “Kangaroo Jiggers,” one that may not have been published. Another few were pieces by Hager, one being from his “Wildflower suite,” which was recorded around 1915.

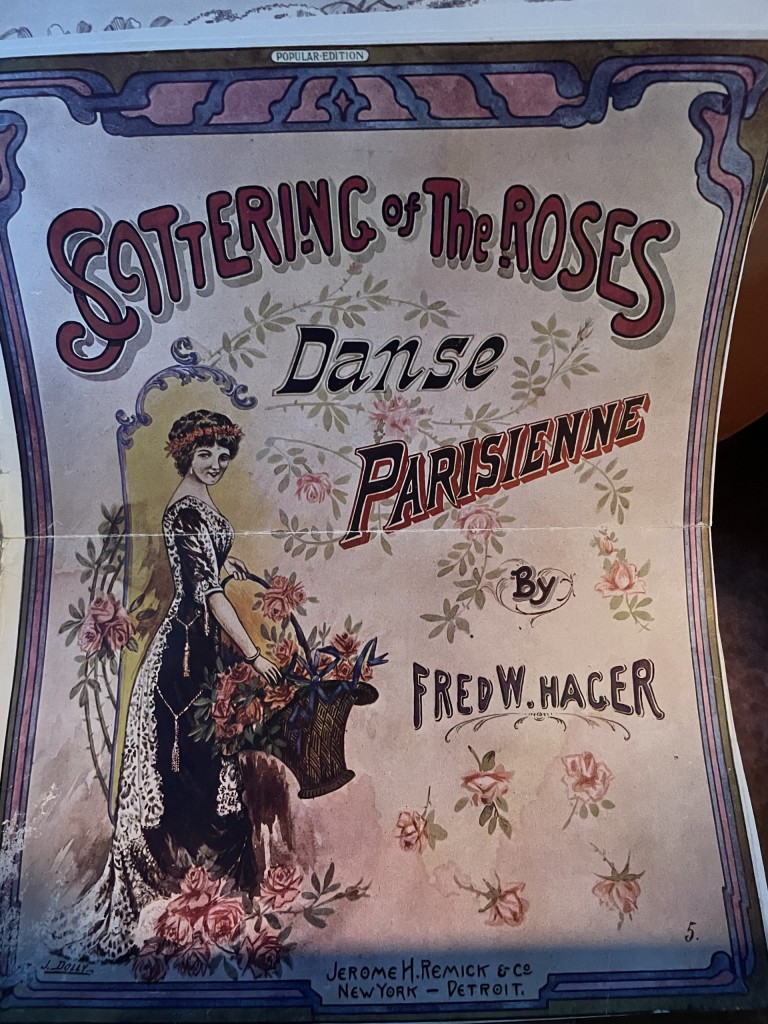

As I dug deeper, I found many pieces of sheet music that were marked with his personal stamp in blue ink, PROPERTY OF FREDERICK HAGER. Many of these sheets were untouched, but others had been doodled upon by Hager himself. Some of them had reminder notes on them, but others had very strange doodles that appeared to be pitches for other sheet covers. He wrote notes and reminders on what seemed like any piece of paper he could find. Some pages were dedicated to lyrics alone, most of which were not very well written (and poorly typed), but a few were more absurd. One of them without a date (but probably from the 1930s) was called The Toilet Seat, written in some type of dialect, and was a little off-color. Something that is curious to note about what was in this stash is that very little of it had to do with actual recording. There were no catalogs, supplements, etc, but there were a few autographed photos of recording stars. The most interesting one to note was that of Arthur Collins. It is likely that Hager had much more ephemera like this, but he gave it away.

There was no way I could have poorly photographed everything that was in the stash, as did I mention we were in a moving car as this was happening? Among the most interesting and historically significant things I saw in there was an original draft of Ring and Hager’s first piece together, I’ve Got my Eyes on You. This piece was originally self published in 1902, but it seems that the piece goes back to at least 1901, as Ring (or Hager) wrote at the bottom of the page. The lyrics are nothing like the final published version (of which there was also a copy in the folder with this manuscript), and are a bit more overt than the published version. Clearly this piece meant quite a lot to Hager, the fact that it survives (though there are burn scars on the top corner) speaks volumes. There were also two copies of this manuscript, not just the one.

Although there were no letters to or from Justin Ring, Hager indicated on several pages that there were many at one time. Where they all went is another thing to discover. They do not exist with Ring’s family as far as I and his descendants know. Perhaps they were burned? Who knows. There is still plenty to uncover.

It was fascinating to be able to put these pieces together with the papers of Hager’s I already had. It was clear that all of these papers were once stored together. Even though they had been spit by many thousands of miles, they once all lived in this trunk. Going through these papers is as close as one can get to meeting the man, the material itself speaks to everything about Hager. Seeing these doodles and drafts get us into his head, and truly give us an intimate look into how he thought. Hager had a large personality, which can be evident from pictures of him, and was also at times uncomfortable to be around. All of these things made him an effective hustler for his band and partner Justin Ring, but this difficult personality is why his papers were scattered. He would certainly be over the moon knowing that someone like me so many years later cared so much about his music and career, as he was in the last two decades of his life.

It was fascinating to be able to put these pieces together with the papers of Hager’s I already had. It was clear that all of these papers were once stored together. Even though they had been spit by many thousands of miles, they once all lived in this trunk. Going through these papers is as close as one can get to meeting the man, the material itself speaks to everything about Hager. Seeing these doodles and drafts get us into his head, and truly give us an intimate look into how he thought. Hager had a large personality, which can be evident from pictures of him, and was also at times uncomfortable to be around. All of these things made him an effective hustler for his band and partner Justin Ring, but this difficult personality is why his papers were scattered. He would certainly be over the moon knowing that someone like me so many years later cared so much about his music and career, as he was in the last two decades of his life.

While it might seem that the mystery of Hager’s steamer trunk has been solved, there is still a lot more to find. I have yet to spend hours of meditative time going through all of what is left. There are still more pieces out there than once belonged to Hager. It is in fact possible that many of Hager’s own records are scattered in our record collections. Many of the surviving Zon-O-phone test pressings likely were in his collection at one time. I actually have one of his records in my collection (it came with the scrapbook when I bought it).

Not only will I never forget seeing these papers in person, but the adventure that went along with it. The chaos of the moment seemed appropriate to the apparent chaos Hager could bring to any situation. There is more to be seen and held, stay tuned for more!

The author expresses her thanks to Don Seubert for his kind help and encouragement, and for sharing Hager’s documents with her.

R. S. Baker has appeared at several Ragtime festivals as a pianist and lecturer. Her particular interest lies in the brown wax cylinder era of the recording industry, and in the study of the earliest studio pianists, such as Fred Hylands, Frank P. Banta, and Frederick W. Hager.