Musicians who worked in phonograph studios in the acoustic era were basically forced to fend for themselves for pay. The Musicians’ Union as we know it did exist starting in 1896, but there were still many things to improve on it. What is interesting is that, during the acoustic era, many unions were founded and organized within the world of the arts, but none of them had to do with recording.

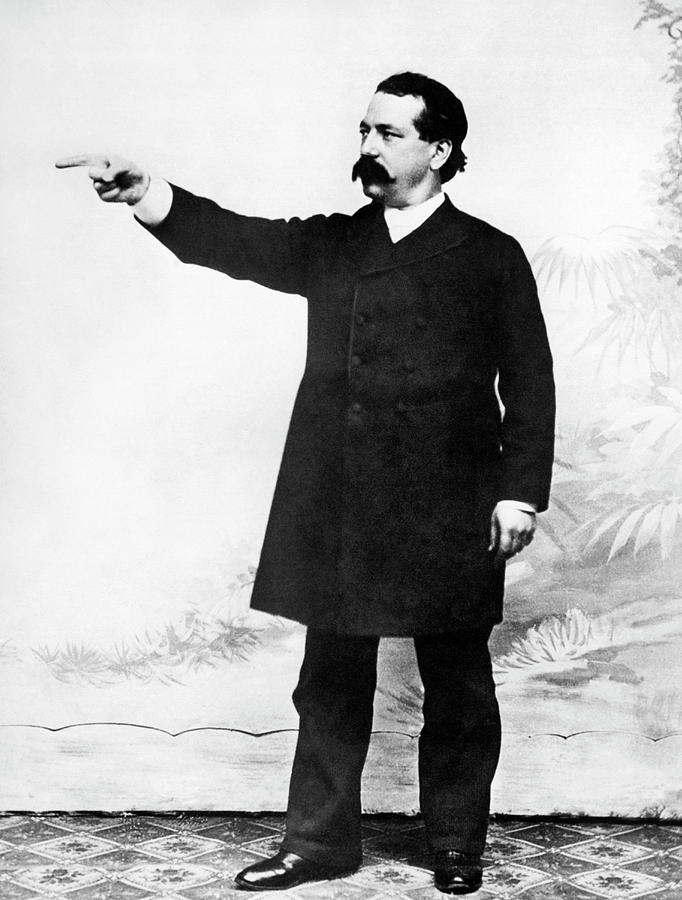

Recording before 1925 was difficult; this has been well-established in this column. Once many musicians heard what it was like to make recordings, most of them vowed they would stay away from them. John Philip Sousa was a prime example of this mindset, famously being very opposed to recording in general. However, he only thought that recordings in the long term would delegitimize the appeal of live concerts and musicians—he wasn’t considering how difficult the process was.

There were very few musicians before 1910 who would have even considered recording, sharing similar beliefs to Sousa. But there was one musician two years younger than Sousa who had the opposite feelings surrounding recording. Edward Issler thought differently than most musicians of his generation; rather than find recording only a novelty, he found it to be one of the most fascinating things invented at the time, and therefore embraced it.

Issler became one of the most recorded people of the 1890s (if not the most), not just making the records with his small orchestra, but also taking part in the experimentation of the process. During the decade or so that he made recordings (1889-1899) he was, like all others at the time, forced to make records by the round, as in playing the same song dozens of times to meet the demand of certain titles. This, as could be expected, was extremely tiresome, so only the toughest people would actually last this gruesome process. Issler and his five other musicians endured sometimes 12 hour days of this process, and oftentimes, especially before 1892, they also had to keep track of the ledgers, filling in each title they performed.

It is likely because of this that Issler left recording so early, and why in 1896, right at the beginning of its history, he became a charter member of the Musicians’ Union. At the time it was formally organized, it was called (and sometimes today) the American Federation of Musicians. Issler was proud of his position within the union, becoming one of the most recognized men in Newark, New Jersey, because of it. At the time, Newark was home to many musicians who worked in New York—as much like today, it was cheaper to live there than in the city itself. In the years after the formation of the union, Issler likely encouraged many of his fellow musicians to join, and soon other phonograph musicians were joining unions left and right.

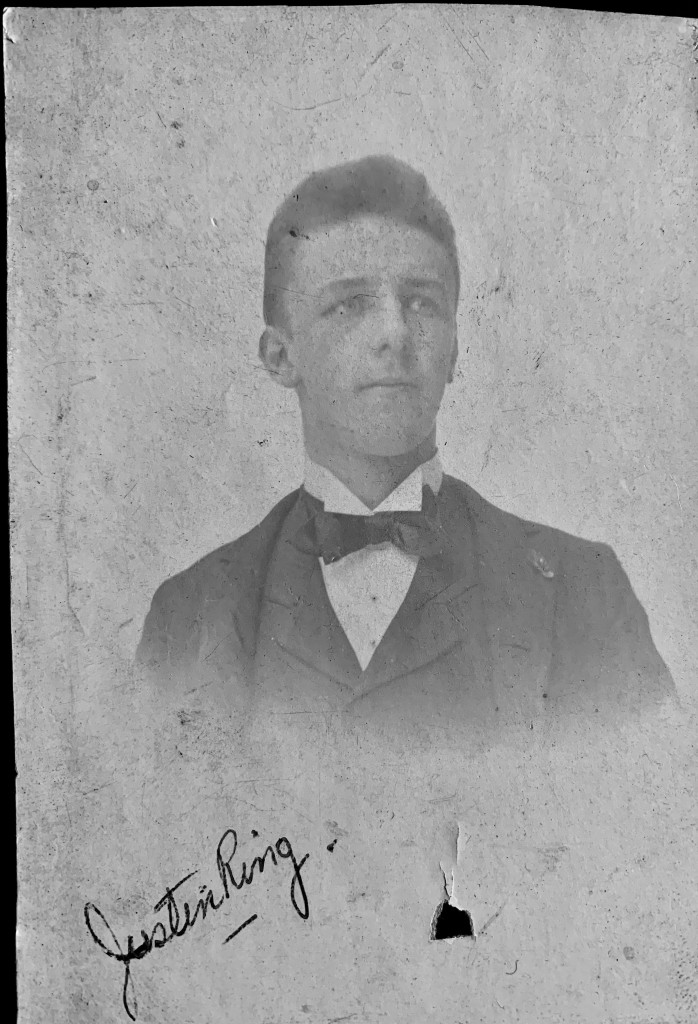

Justin Ring recalled in a short autobiography that,

At that time there wasn’t any musicians union so I joined Samuel Gompers who was very active in the cigar makers union. A few years later I became a charter member of Local #802 of the musician’s union…

While this excerpt is very vague, it does say quite a lot. Ring at the time of wanting to join the forming Musicians’ Union was one of the youngest advocates in the field. While we do not know exactly when he began, we can be sure it was before 1896. He would have been in his late teens at the time. It is also very notable that Ring, even as a teenager was engaging with giants like Gompers, who, although he knew nothing of the music world, was willing to find some sort of understanding with the young firebrand from Avenue A. It is also very likely that Ring was well acquainted with Issler, not just in the recording world, but also in the local 802. Issler and Ring stayed in the union even while they were basically slaving away in recording studios. Issler probably got fed up with this tedious work, and left recording around 1900 to focus more on the rights of his fellow musicians.

Also in 1900, another important union began to organize, the White Rats actors’ union. At that time, only a few men owned most of the newly built theaters in the United States, and this started to wear on the many actors and performers who worked for them. Many recording artists joined this union right at the beginning, two of them being Edward M. Favor and Will F. Denny.

As helpful as this was, this still had nothing to do with recording. Recording at this time was seen more as a gig for the singers and actors who made them. For the singers and featured musicians, this was fully the case, as their actual line of work lay elsewhere. Fred Hylands famously joined this union around 1902, likely because of the influence from his fellow recording folk. Unlike the others, Hylands rose up the ranks in the White Rats, becoming one of their most notable members. We can be sure that part of the reason Hylands disappeared from recording at the end of 1902 was because of this sudden change in opinion. He had begun his time in recording at the end of the round era, so he did have a valid reason to leave so quickly. Hylands stayed with the White Rats until his death in 1913.

This was a bit different for the staff musicians however. Most of them still worked regularly in orchestras and outside bands, but there were a select few whose job was actually in the studio. Justin Ring was one of these musicians. He was working at regular gigs until 1900 when he started making records with Fred Hager. Although he still considered himself a traditional musician, at that point he was working exclusively for record companies.

The working conditions even at the beginning of Ring’s career in recording was certainly not kosher for the Musicians’ Union. The era of the rounds had passed, but he and Hager were working for so many companies at the same time that the amount of work was essentially the same. Additionally, he and Hager also had to basically run Zon-O-Phone because the management was so often in court for patent litigation. Not to mention that Ring played several different instruments in more than one orchestra Hager led. Surely the union found this amount of work abuse perpetrated by Hager. Regardless of what the union thought of this, Hager was made an honorary member. His paperwork and identification card still survive to this day.

Another musician was Frank P. Banta. Banta, as stated by more than one of his obituaries in 1903, that he was a member of the union as well. These sources also stated that he was part of a German based union as well. This might come as a surprise, as Banta was quite literally the first victim of overwork in the phonograph business. Somehow the organizations he was part of saw little to no reason to include recording into their protections, even if this was the thing that was killing him slowly. Things did change after his death, as many studio musicians only stuck to one or two companies instead of more. Thankfully at this time, a new generation of musicians and performers entered in the business to add more diversity to those working there.

Even into the 1910s, Issler was still very well respected and acknowledged for his accomplishments in the Musician’s union. Several sources in the mid 1910s mention special Masonic events held in his honor, showing that many other musicians and recording folk found his impact significant. Although it took many years for unions to consider recording a legitimate business that needed to be regulated, it did eventually happen once Hollywood began to take over as a media capital.

Some former recording studio musicians were invited to work in Hollywood, one of them being Jimmy Hager. Hager had been working constantly as a musician since about the age of 15, and by 1928 had seen every improvement in the technology. He was skilled enough as a percussionist to be offered this job, but declined. In the long term it was generally better that he didn’t move his whole family to California to begin a new life after already having one. There is also little evidence that he was in any sort of union, making him an obvious outlier in the business. He wasn’t in the Masons either, another thing that was extremely common among his comrades.

Nowadays it can be difficult to book any sort of recording session in Hollywood without permission from the Musicians’ Union. This is quite a difference from the shunning of recording in its earliest days.

R. S. Baker has appeared at several Ragtime festivals as a pianist and lecturer. Her particular interest lies in the brown wax cylinder era of the recording industry, and in the study of the earliest studio pianists, such as Fred Hylands, Frank P. Banta, and Frederick W. Hager.