Every pianist has their own style, and as we study the accompaniments of the earliest acoustic recordings of the regular studio pianists of the 1890s and 1900s their different styles are obvious. Of these, one pianist clearly stands out from the rest. Fred Hylands was not from the East Coast, where all the other pianists came from. Hylands was from one of the regions believed to be the cradle of ragtime, and from this brought a unique style that can still educate listeners about vernacular styles of music. He was able to make even very mundane and simple accompaniments very interesting and distinct. Although forgotten in the century after his death, Fred Hylands’ accompaniments preserved an authentic ragtime style that wouldn’t be known to us otherwise.

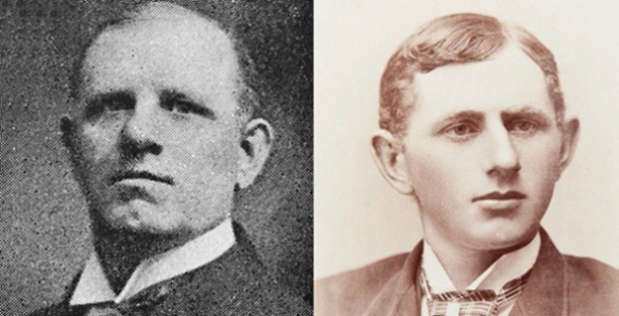

In 1896, the newly established musical craze of ragtime spread throughout white society, and took the music world by storm. At the same time, the Columbia phonograph company was setting up their new headquarters at 1155-1159 Broadway in New York, and with this big move from Washington they were looking for local talent. Edward Issler was still their primary accompanist at the time, but they were likely auditioning many other pianists for the job. Certainly Hylands charmed them and proved that he was a truly gifted accompanist, aside from his refined knowledge of ragtime. He also likely stood out from others they auditioned because of his imposing height, figure, and bright red hair. Even though he was loud and flamboyant, always making clever jibes at the performers, he could listen to them extremely well, and even in some cases anticipate the movement of the song. This made the ability of his accompaniments outstanding among all the others in the phonograph business at the time.

And then there was the ragtime. Columbia knew that hiring Hylands would be an advantageous move, as this new musical craze was sweeping the western world. From the beginning of his time there, he was playing that distinct syncopated style that was only hinted at in previous years. Listeners began to notice, and with this Columbia made sure to highlight and name the pianist responsible for this change in accompaniment on their records. While not from a Columbia catalog directly, this piece from The Phonoscope in July 1898 sums up the increasing hype of Hylands’ accompaniments:

Frederic Hylands, whose talents are now devoted to making Columbia records, is prominent as a pianist and composer. He has been musical director of some of the leading comic opera and musical comedy companies and pianist with Keith, Pastor, and Proctor of New York, and Hopkins’ and the Avenue Theatres in Pittsburgh. Mr. Hylands’ ragtime piano accompaniments, in fact all his playing for singers, has added much to the popularity of the songs thus added. Among his latest compositions are: “Old Fashioned Girl,” “Narcissus” Gavotte, and “Darkey Volunteers” March.

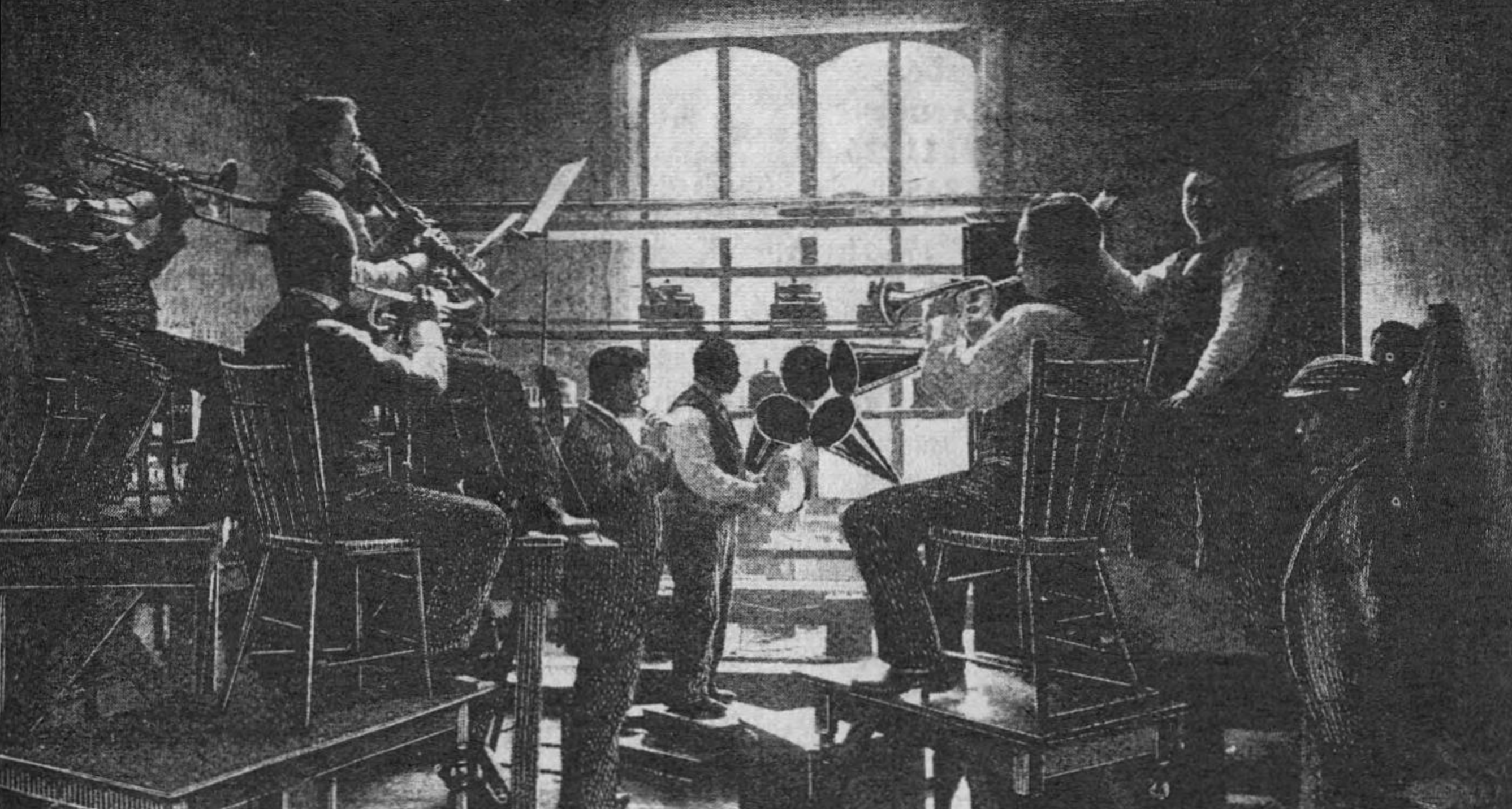

On the same page, Hylands is pictured in a very miniscule photograph of the Columbia orchestra in their lab, at the piano of course. Soon he was all over phonograph trade publications. Even with the publicity and favor, Hylands has yet to be found explicitly mentioned in a Columbia catalog or supplement.

What made him distinct was the “Cincinnati swing” in his playing. Unlike the other phonograph accompanists who he worked alongside, there was a distinctive lilt in his rhythm. He often incorporated eccentric methods of syncopation into this rhythm as well. It made almost every note he played seem syncopated, but he nearly always kept perfectly in step with the performer. It is what makes his accompaniments so addicting to listen to.

His records aren’t hard to come by, as he made so many, and for enough years to have a substantial legacy. He started at Columbia in 1897, and remained there regularly until at least the end of 1901. And now, it is believed, that he also worked occasionally for Zon-O-Phone and Berliner. His talents as an overall accompanist weren’t just clear to Columbia. When he was needed to accompany certain artists, such as George W. Johnson or George Schweinfesst, he was called in. Even infamously difficult performers quite liked him, such as Vess Ossman. Ossman liked very few accompanists, as he was very particular about what they were to add to his solos. Ossman liked Hylands so much that he, unbeknownst to Hylands, had his own arrangement of his “Darkey Volunteer” published with no credit to Hylands. After Ossman went on his very consequential tour of England in 1900, the piece became associated with Ossman, soon showing up in English banjo folios. If Hylands ever caught wind of this, he was likely outraged.

This kind of behavior was to be expected of Ossman, but leaving behind any mention or trace of Hylands’ contributions was an unexpected pattern throughout those who worked with him. Before Ossman claimed it for himself, he did record the piece for Zon-O-Phone at the very beginning of that company’s existence.He admittedly found working for Columbia very tiresome, and barely worth the time and money. Although his complaints were taken as humorous, he certainly didn’t find Columbia the most comfortable place to work. It is not known exactly what the work day was like there, but one account by an Edison musician made it out to be quite taxing. He stated that he had to be there by eight in the morning and would be finished with the day by six, or later depending on the quality of the records made and the amount of takes needed.

In the late 1890s, Columbia insisted that their talent show off the wondrous technology and process of recording to the public in exhibitions. These were commonplace within all record companies at the time, but Columbia took them a step further. The performers would host these programs for several hours a night, probably after a day of recording had already been done. They were held in the elaborate first floor of the Columbia building at 1155 Broadway, lit by hundreds of electric lights. Hylands often took other gigs outside of Columbia as well (as musicians do), so one could wonder when he ever had time to rest while working for them. It was likely this that brought him to join a performers’ union not long before he stopped showing up on Columbia’s records.

It was incredibly rare for these regional styles to have been recorded at the time, other than by local record companies, whose records are nearly impossible to find today. It is entirely possible that before Hylands left the Cincinnati area in 1892-93 he might have attracted interest of the local record company (which was substantial by that time), but finding evidence of this would prove difficult. Many of these vernacular styles were recorded at the very end of the ragtime era, but by the end of the 1920s these styles were becoming less distinct (an example of this is Benny Moten’s Kansas City records).

With all of this in mind, Hylands unknowingly preserved one of these ragtime dialects before the beginning of the 20th century, but it was just another gig to him. Oftentimes his accompaniments on Columbia are some of the best examples of piano ragtime recorded in the era. Even though he was hidden behind haughty singers and diva instrumentalists, we can still hear his Cincinnati-Indiana style, 110 years after his death.

R. S. Baker has appeared at several Ragtime festivals as a pianist and lecturer. Her particular interest lies in the brown wax cylinder era of the recording industry, and in the study of the earliest studio pianists, such as Fred Hylands, Frank P. Banta, and Frederick W. Hager.