In 1899, recording artist Len Spencer decided to make a bold move: take his small group of phonograph friends on tour in a minstrel troupe. While minstrel shows are now considered insensitive and unsightly to people today, they were at one time a mainstay of American and European entertainment. After many months of planning and gathering the funds to accommodate, he was able to spend the end of 1898 into 1899 playing in various theaters, even with a terrible blizzard threatening to throw off the entire journey. A number of important things happened while he was on tour however, and when they all came back, the Columbia phonograph company was in shambles; it seemed that the old tight-knit crew would never be able to darn itself back together.

Since the beginning of his recording career (1888-89), Len Spencer had an idea to start his own troupe. In 1893, he decided to start an ambitious project that would end up being the first of its kind. He gathered a group of his closest friends in the phonograph world and made a series of minstrel show recordings, that were intended to be sold together as a set. What was unique about these recordings wasn’t just the nature of the content and sales, but was also that they included a black recording artist as the lead, George W. Johnson—something that was very rarely done with white minstrel troupes at the time. This troupe did not perform live as far as it is known, but it would pave the way for what was to come.

The rumors of this troupe started going around in the inside of the phonograph world around the middle of 1898, with their first performance as a group in November of that year. While the first few shows were purely live entertainment, the underlying purpose of these shows was to exhibit the unique abilities of the (Columbia) phonograph. One such entry from the January 1899 issue of The Phonoscope described it thus:

Len Spencer’s minstrels have met with great success during their recent trip. The company embraces many of the leading vocalists in the phonograph profession. One of the most interesting features of the big bill was the introduction of the Graphophone Grand, which was personally conducted by Mr. Len Spencer. At the close of the entertainment a blank cylinder was placed on the machine and the band started to play a popular air, the audience being invited to join in. The whistling in the gallery was plainly audible.

It is unknown whether this cylinder or others from these performances still exist to this day.

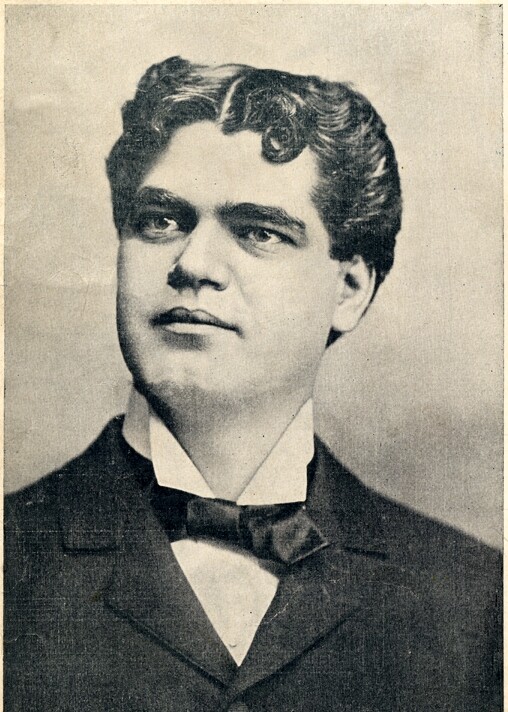

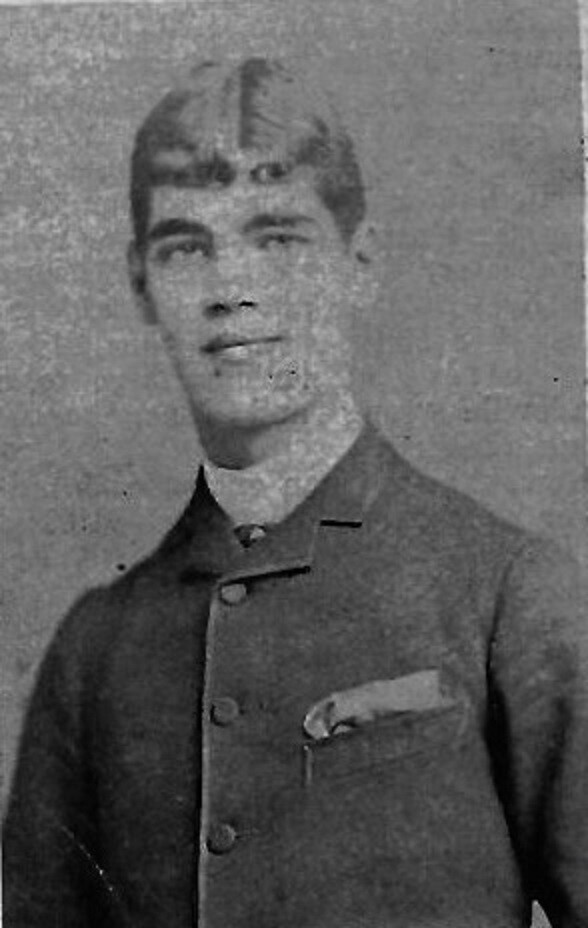

These performances got more elaborate as Spencer was able to acquire more talent and a better agent to make for a better show. Usually the shows always included names such as Billy Golden, Roger Harding, Steve Porter, Vess L. Ossman, musicians of the Columbia orchestra, and Fred Hylands.

By the end of the fall, the shows had picked up again, even with all the amount of work Spencer was already doing for Columbia, were able to get everyone together for some full-on minstrel shows. This time the dream he had for nearly a decade truly came to life. According to sources outside of the phonograph world, the performances were packed, or at least very close to sold out. Soon posters with a caricature of Spencer all in his stage attire were hung up in occasional theaters. One of these such posters still exists and at one time was in the collection of Jim Walsh; now it is preserved by the Library of Congress.

In November, with the first few shows proving well, Spencer decided that he should take the group on tour. All the shows they had done previously were done on their own, but he finally had the resources to plan a full fledged tour. He and Fred Hylands planned out a tour that mostly consisted of towns on the eastern edge of New Jersey, just outside of New York, and up into Connecticut. This was a typical minstrel show production, with various rotating acts within the Columbia phonograph company talent depending on the night. At a few of these shows, Hylands not only played piano, but also assumed the ever-important role of playing the bones and telling jokes.

Unfortunately, during this tour George W. Johnson had to be cast aside, since it was still considered rather rash at the time to have a mixed-race cast onstage. Johnson had also run into some personal issues at home, that, when they all returned, would tear them apart.

In December, they ran into more trouble when a huge blizzard struck New York, and it forced them to be stranded for a few nights and a few of their shows were canceled. Spencer feared the worst, but in his very determined way, intended that the next few engagements would go on. If you comb through various photographs dating from late 1898 in New York, the great destruction and inconvenience this blizzard caused is very clear. After a few days, the streets were cleared out enough that by Christmas the troupe was back on the move.

A few weeks later they set off again for a few theaters in Jersey and Connecticut. They had a few major sold out shows in Asbury Park, New Jersey, which were prominently advertised in the local papers.

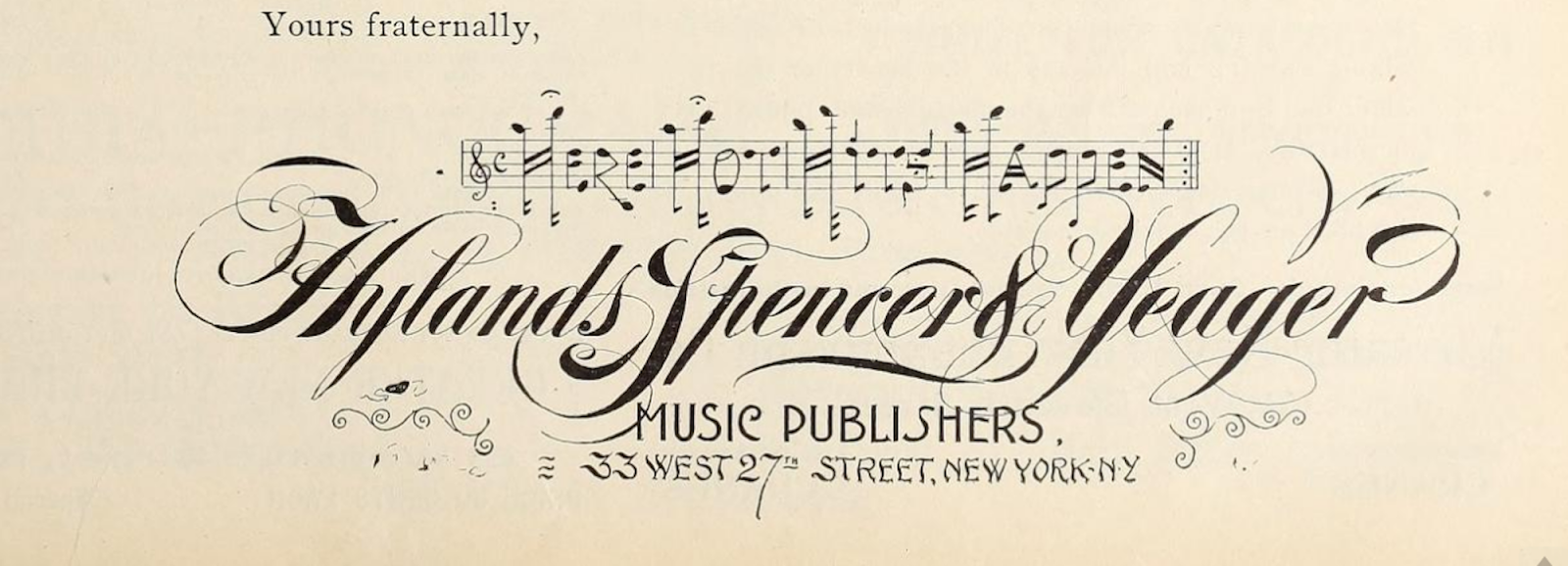

With all this success and tight bonds formed through these shows, in February of 1899 Spencer teamed up with Fred Hylands and Harry Yeager to establish a publishing firm, formally uniting the phonograph and music publishing for the first time. Spencer regarded Yeager as one of his most valuable promoters, as he was not only a skilled singer, but a well connected booking agent. From then on, Spencer engaged Yeager as his minstrel show producer. Hylands was also very well connected in the minstrel world, bringing the most aggressive and fringe ragtime into the firm and the shows.

By April, the publishing firm was well established, and earning lots of money and acclaim in the competitive safari that was Tin Pan Alley. They had published a few modest hits by then, earning a reputation on the vice-ridden row that was 27th Street. While Hylands led the way buried in these vices, Spencer and Yeager worked hard at “33,” the address number of the firm, and down the block at the Columbia company, the performances halted for a little while as the firm grew. During this time Hylands’ home base served not only as the location of the publishing firm, but also the booking office for Spencer’s minstrels.

According to all sources, their shows became even more smooth going and refined, with lots of variety and class acts, all connected to the phonograph in some way. It soon became expected to have some performance in the area immediately surrounding the Edison plant in Orange New Jersey, a rather strategic and convenient location to exhibit the Columbia machine and talent. While the shows diminished, the popularity of the publishing firm increased, and everyone at Columbia was raking in the dough. For once Fred Hylands had proved to everyone that he had some good ideas and intentions after all.

But, by the end of 1899, everything was starting to crack. In December 1899, George W. Johnson was put on trial for the suspicious death of his common law wife, Roskin. By this time Hylands had fallen out with several of the original minstrel troupe, and alienated many of his most moneyed donors (such as Roger Harding). Hylands and Spencer backed the defense in favor of Johnson, and Hylands even sent in one of his own lawyers to provide some of the most notable testimonies for the case.

Even though the trial had blown over and left Spencer and Columbia unscathed, the troupe was a mess, and Hylands was losing money fast. Spencer had also suffered some almost serious medical problems from the amount of stress he endured over the previous year. As a result, he was starting to change his mind about taking on such ambitious projects, even though he was merely 33 at the time. By the middle of 1900, they rarely performed as a troupe, as Spencer had started to sing much less. Also by this time, everyone had lost faith in Hylands to keep their investments together and they abandoned the publishing firm. By fall, Spencer had formally left, leaving any engagements with Hylands behind as well. They still performed together often on records, but the amount of work Spencer did was dramatically diminished.

Such ambitious ventures that Spencer took on wouldn’t be attempted again until the end of the next decade, so his efforts were not in vain. After this point, the tight-knit community that kept the core of the phonograph business fell to pieces, and paved the way for the next generation of popular singers and musicians at the start of the molded cylinder period.

R. S. Baker has appeared at several Ragtime festivals as a pianist and lecturer. Her particular interest lies in the brown wax cylinder era of the recording industry, and in the study of the earliest studio pianists, such as Fred Hylands, Frank P. Banta, and Frederick W. Hager.