The role of each instrument in a jazz ensemble has changed as the music has changed, but the most dramatic transformation has been the role of the bass. Initially, the string bass was a mere imitator of the tuba’s oom-pah, outlining the harmony and helping maintain the rhythm and pulse. But, for the last fifty or so years, it’s increasingly expected that bass players move between supporting roles as members of the rhythm section and equal participants in soloing.

Some of the key players who get credit for evolving the role of the bass are: Bill Johnson, Steve Brown, and Wellman Braud in the 1920’s, Jimmy Blanton in the late 1930’s and Oscar Pettiford and Paul Chambers in the 1940’s and 50’s. But there are two bass players who, although well known, are not fully appreciated for their importance in moving the bass to the front of the bandstand: Slam Stewart and Major Holley. They accomplished this largely because of their genius in using the bow-and for the ability to use their voices in tandem with their bowed solos.

The earliest work on “the bottom” in jazz was most often done by the more easily heard tuba or sousaphone. The best way for the string bass to imitate that sound was by using pizzicato-the plucked string. In the studio, the attack of a single note by a tuba or a plucked bass string was much easier to record in the era of acoustic recording, which continued until the mid 1920’s. With the introduction of electronic recording, the string bass began to supplant the tuba. There was a transitional period and for a few years it was easier to get a gig if you played both, but within a few years, string bass replaced tuba except in some bands that played traditional New Orleans jazz.

Apart from pizzicato, there was playing using a bow-the more standard approach in classical music, called “arco” playing (Italian-“arco”-bow, from Latin arcus). In 1920’s jazz there was some arco playing-not soloing-notably in parts written by Duke Ellington for Wellman Braud, as in the tune “The Blues With a Feelin’” from 1928.

Then, in the mid-1930’s, Leroy Elliot “Slam” Stewart arrived on the scene (1914-1987). From New Jersey, Stewart went to the Boston Conservatory of Music and heard violinist Ray Perry in a club singing along with his violin, which inspired him to do the same with his bass. He began freelancing in New York City in 1935 and started playing in that style. That’s when he got his nickname: ”At times, I slapped the bass when I played,” he told The New York Times. ”It had the same sound as a slam. They gave me the name Slam, and I’ve been stuck with it ever since. But I’m very used to it and prefer it to Leroy.”

He found a compatible partner in singer/pianist/guitarist Slim Gaillard and in 1937, they formed the group “Slim and Slam.” The duo had a unique sound that straddled swing/bop and early R&B and in 1938 they broke through and had a hit with “Flat Foot Floogie”. Listen for Stewart’s arco work-completely unique at the time.

One may also find on YouTube Stewart’s masterful 1945 performance of “After You’ve Gone” with Benny Goodman’s sextet, and this well-known version of “I Got Rhythm” from the same year with tenor saxophonist Don Byas. On the latter recording, Stewart is in full voice, singing both in unison and in harmony with his complicated bass lines.

One may also find on YouTube Stewart’s masterful 1945 performance of “After You’ve Gone” with Benny Goodman’s sextet, and this well-known version of “I Got Rhythm” from the same year with tenor saxophonist Don Byas. On the latter recording, Stewart is in full voice, singing both in unison and in harmony with his complicated bass lines.

Major “Mule” Holley, from Detroit, was a decade younger than Stewart (1924-1990). Holley first played the violin and tuba and said that in 1939 when he heard a Slim and Slam record called “Champagne Lullabye” he decided to take up the string bass: “I elected to play that style because it intrigued me how anybody could make a bass sound like that…I like the freedom. If I want to sound like a jet plane taking off, I can do it.”

Major “Mule” Holley, from Detroit, was a decade younger than Stewart (1924-1990). Holley first played the violin and tuba and said that in 1939 when he heard a Slim and Slam record called “Champagne Lullabye” he decided to take up the string bass: “I elected to play that style because it intrigued me how anybody could make a bass sound like that…I like the freedom. If I want to sound like a jet plane taking off, I can do it.”

Stylistically, he was a swing and “mainstream” player whose soloing is very similar to Slam’s, but his voice is distinguishable by the fact that it’s both more nasal and also commands the deepest registers. So, while Stewart often sang an octave or two above his bass, Holley often sang either in unison or just an octave above. His bowing and basso profundo may be heard on video footage of Internationale Jazzwoche (International Jazz Week) in Burghausen, Germany, in 1990 and in a 1974 session performing “Angel Eyes.”

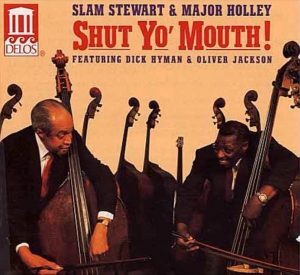

The careers of Holley and Stewart followed similar paths. They played with many of the same people and both worked as sidemen for Art Tatum and Benny Goodman, but they didn’t meet until 1961 and didn’t record together until 1977. Here are Slam and Major together, with a parody version of “Close Your Eyes” from their album Shut Yo’ Mouth. It’s kind of astonishing that this level of virtuosity and musical skill was done in almost a throwaway fashion. After this primer, you should be able to tell who goes first and who goes second.

Also from Shut Yo’ Mouth one may hear a remarkable version of “Undecided.”

The man who picked up the mantle of arco greatness from them was Paul Lawrence Dunbar Chambers. Known as P.C., Chambers (1935-1969) was, appropriately, about a decade younger than Holley. Both came from Detroit and studied at Cass Technical High School-must be something in the water. Chambers picked up the arco baton from the Swing-era Holley and Stewart and brought it into the rarified harmonic realms of Bop. Here’s an example of what he could do. He takes the last solo on a live version of “Walkin’” (recorded live with John Coltrane in 1960). (The video is is from Coltrane’s first trip overseas, touring as a member of one of Miles Davis’s first great quintets. The footage was taken on March 28, 1960. in Düsseldorf, West Germany, a night Miles Davis sat out.)

Stewart and Holley had successful careers and played with the greatest jazz musicians of their respective eras; influencing generations of bass players, such that, by the 1960’s, it was common for bass players to use bows as part of their musical arsenals. (Modern practitioners who excel playing arco in the tradition of Stewart and Holley include: Christian McBride, Edgar Meyer, Michael Moore, Rufus Reid, Ari Roland, Miroslav Vitous, Red Mitchell, Dave Holland, George Mraz and Niels Henning Orsted Pederson. None has surpassed the arco virtuosity of Stewart and Holley).

There was no weakness in the playing of Stewart and Holley who, apart from their special skills could also “walk” the bass as well as anyone ever has in jazz. I think the reason they aren’t seen as the influential musicians they actually were is the fact that they developed techniques that were not just musically substantial, but kept audiences entertained.

There’s something intrinsically upbeat about their music and, although it seems odd to say this, I think there is a subtle tendency among jazz critics and writers to undervalue players because their persona and their music don’t carry the requisite gravitas-as if only one part of the spectrum of human values can represent jazz. Jazz has thrived and will continue to because it is capable of communicating the full range of human emotion. Time to give Slam Stewart and Major Holley the credit they deserve

Steve Provizer is a brass player, arranger and writer. He has written about jazz for a number of print and online publications and has blogged for a number of years at: brilliantcornersabostonjazzblog.blogspot.com. He is also a proud member of the Screen Actors Guild.