The year 2021 marks 110 years since the birth of jazz trumpeter Buck Clayton, best known for his role in the classic early Count Basie orchestra and sensitive accompaniments to Billie Holiday on records. This narrative is based on his lovely memoir published 35 years ago, Buck Clayton’s Jazz World (Oxford University Press, 1986).

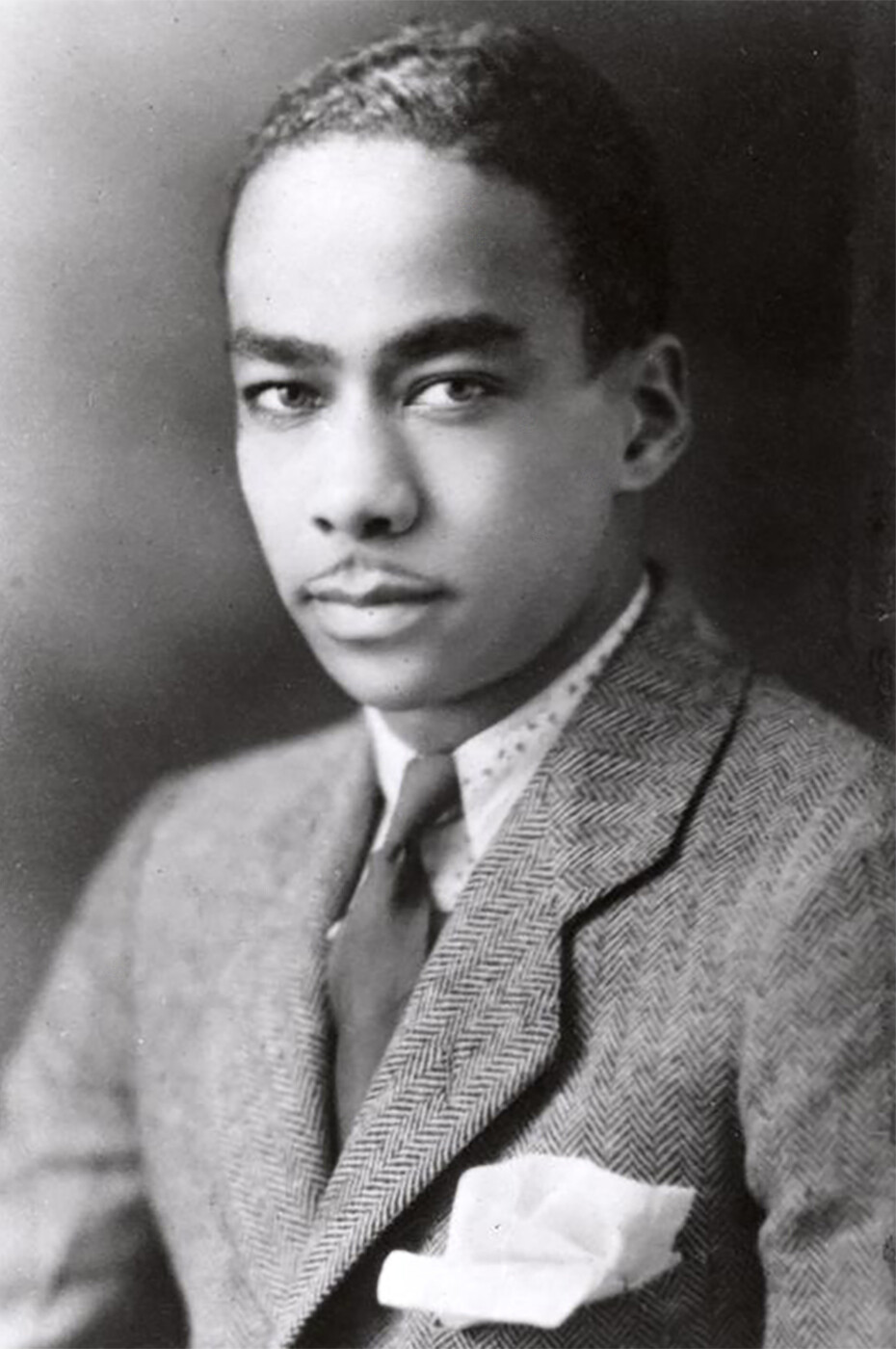

His signature trumpet sound was more intimate and smoother than his contemporaries, featuring a flowing and melodic approach to improvisation, refined tone, imaginative use of mutes and a great feel for the blues. His restrained style and melodic improvising made him a popular soloist and international Jazz star.

Clayton’s sly, muted horn licks were an essential component to innovative hits of Count Basie and his Orchestra. Widely respected among musicians, he was NOT a bravura soloist in the Louis Armstrong manner though he is reported to have displayed greater intensity in live performance, as heard in extant airshots and transcriptions.

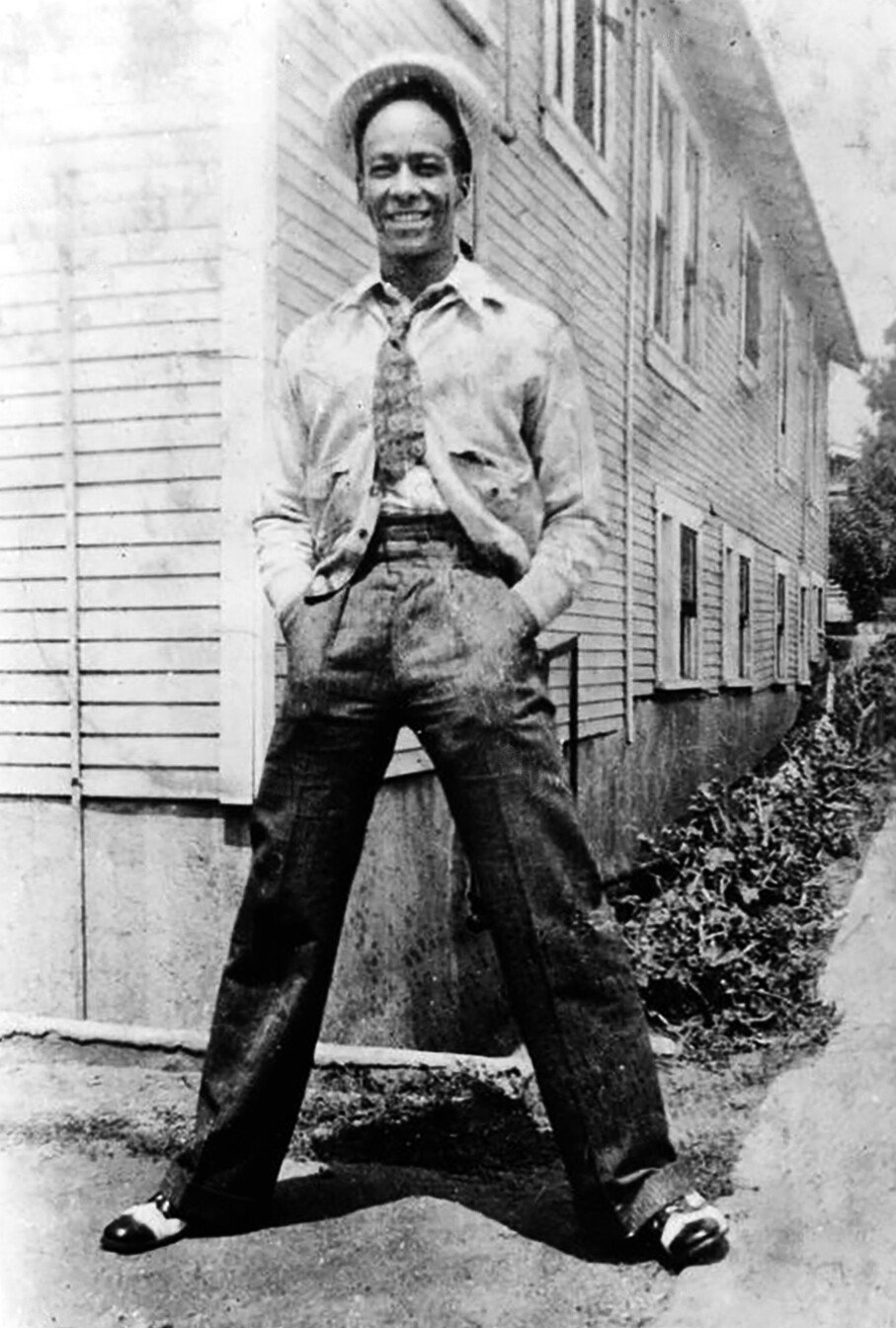

His burnished horn tone and distinctive use of cup-mute graced some of the biggest hits of the Swing era. His stylish wardrobe, striking good looks and memorable blue-green eyes won him the sobriquet “Cat Eyes.” Like his music, this memoir speaks with a distinctive voice modestly describing a life cinematic in scope.

Parsons, Kansas Origins

Wilbur Dorsey “Buck” Clayton (1911-1991) was named for inventor and aviator Wilbur Wright:

“My mother wanted me to have a name that wouldn’t have a nickname . . . However, she defeated her own purposes by nicknaming me Buck. When I was about 12 years old, wild [Native American] boys were known as bucks. She always said that I was pretty wild kid, so she named me Buck because of being part Cherokee Indian on my Dad’s side of the family.”

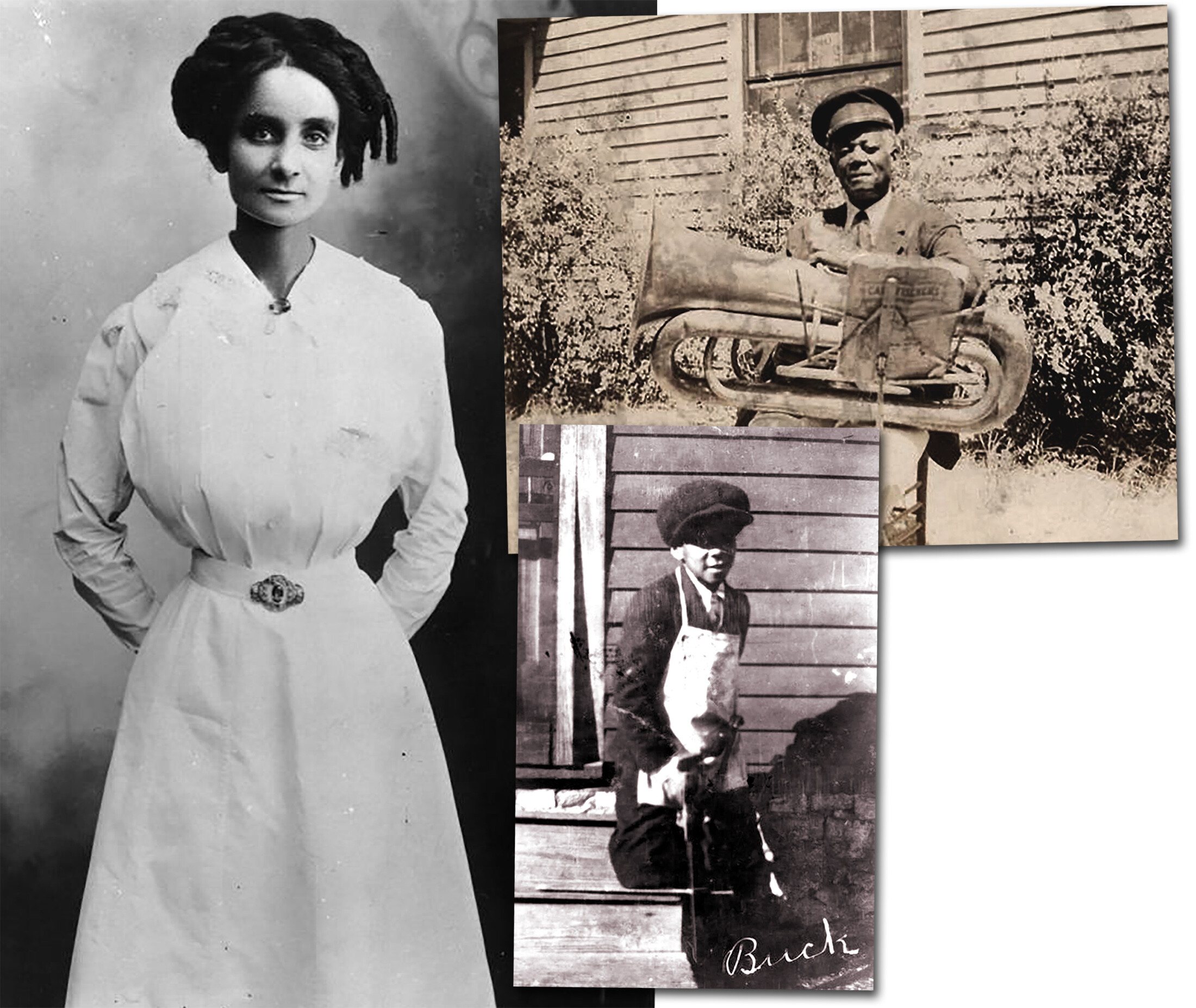

His father, Simeon Oliver Clayton was a capable and erudite man. A newspaper editor, poet and musician, he played brass bass and sang bass in a popular vocal harmony group, “one of the greatest singing groups of the territory” notes Buck.

From his mother Buck inherited a robust sense of morals and ethics. Aritha Anne Dorsey-Clayton was a school teacher, pianist and church-going woman (Methodist AME). He calls her a “freedom fighter” who was friendly with civil rights leaders. She once cleverly accelerated his piano lessons by bribing him fifty dollars to learn Rachmaninoff’s Prelude in C-Sharp Minor. His mother “never asked me not to play jazz, but she really didn’t like it too much,” yet relented after he performed at Carnegie Hall.

All of the Clayton family were musical. Buck became proficient on piano, then studied trumpet with his father so that he could play in the bands at school and church. Incidentally, the only instruction or mentoring that he acknowledges are his father and a hometown friend, another young horn player named Clarence Trice who later recorded with the Andy Kirk orchestra.

An Eagle Scout, Clayton was keen on becoming a boxer, but he and his friends were bored to death. After briefly working as a horn substitute for an ensemble passing through Parsons, he resolved to leave small-town Kansas.

Buck jumped a freight train headed West with his buddy Jack Medlock. The journey turned perilous when they were threatened by murderous bullies — not his first nor last encounter with belligerent white nationalists. Accidentally locked in an abandoned refrigerator car on a siding for a while, they arrived in Los Angeles after six harrowing days: “I swore that I’d never again in my life ride another freight train for anything in the world.”

Los Angeles, 1933-34

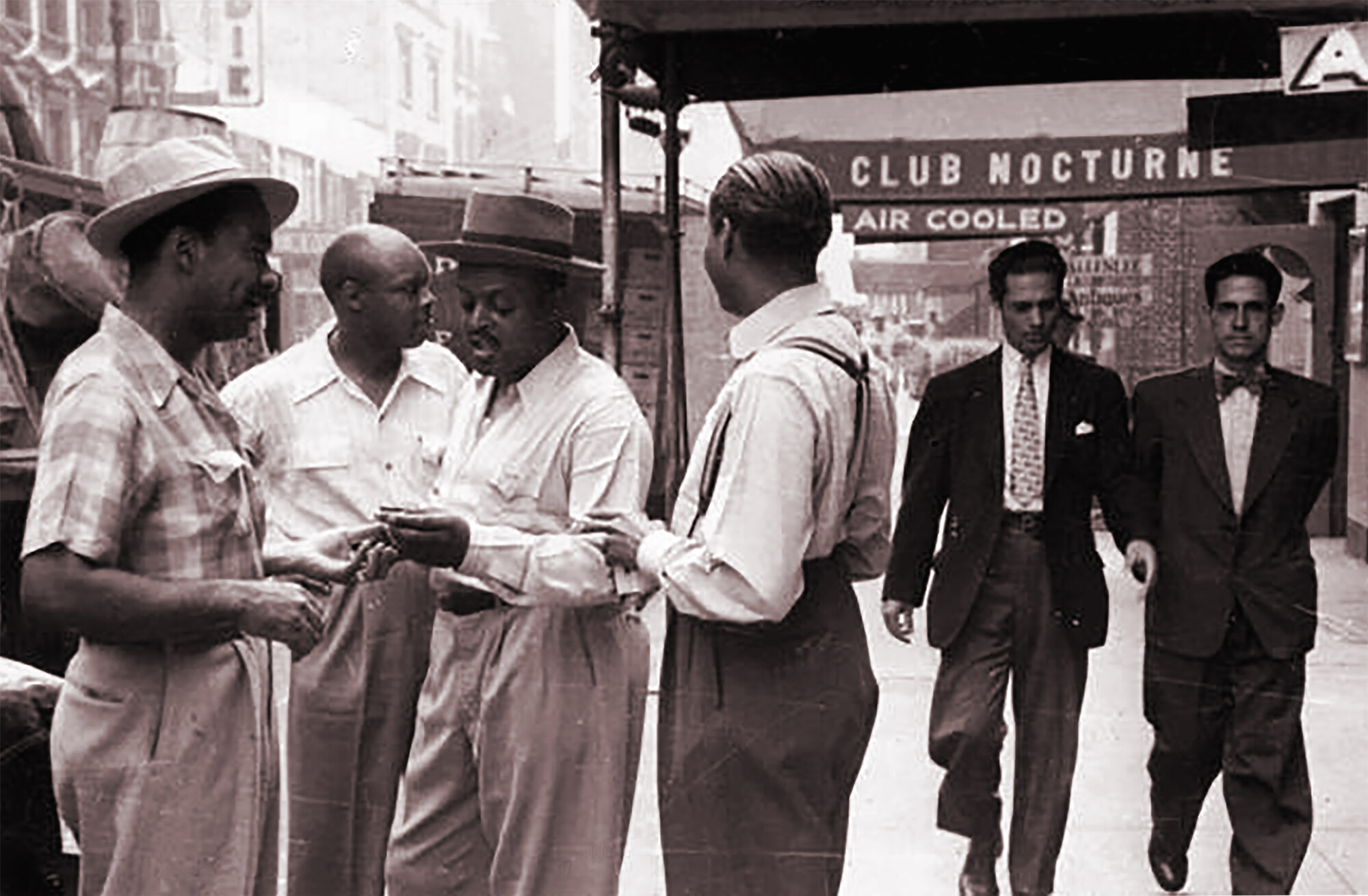

Generally overlooked, Clayton’s tumultuous years out West were formative, molding him into a professional musician. Fresh out of high school he was trying to break into the music business while working odd jobs at a barbershop or a garage. Taking a work as a bouncer at a tough pool hall he was given a hatchet to break up fights, “I never did chop anybody. . . but sometimes I was tempted to.”

He settled into the ethnically diverse community of Boyle Heights, ensconcing himself in the Central Avenue district of L.A., a jumping Jazz quarter. He became acquainted with notable musicians like trumpeter Jack Purvis, bassist Milt Hinton and bandleaders Paul Howard, Charlie Barnet and Lionel Hampton. He attached himself to New Orleans horn man Papa Mutt Carey for a while, but says he wasn’t influenced by his style.

Buck gradually found work playing in the meanest and toughest dives: “Every Saturday night was bloody.” Eventually, he put together a six-piece band of his own for a ‘taxi-dance hall,’ The Red Mill located not far from the iconic Los Angeles City Hall. Calling it “glamourous,” he played for more than a year at this dime-a-dance ballroom that catered mostly to “Filipino fellows. They would wear some of the neatest clothes that I ever saw. . . I admired their taste so much.”

Meeting Satchmo

Buck recalls how stylish Louis Armstrong was when he first saw him:

“His hair looked nice and shiny and he had on a pretty gray suit. He wore a tie that looked like an ascot tie with an extra-big knot in it. Pops was the first one to bring that style of knot to Los Angeles. Soon all the hip cats were wearing big knots in their ties. We called them Louis Armstrong knots. I only saw him for a few minutes, but he sure impressed me just by his appearance.”

It was around this time, and well into his development, when Clayton first encountered Louis’ music, writing “I guess I was spellbound.” Armstrong was then performing at, and broadcasting from Sebastian’s Cotton Club in L.A. In their first meeting, Pops showed Buck how to make a gliss (glissando: a bent note) and introduced him to marijuana.

Minor Celebrity and a Glamorous Wedding, 1934

Clayton worked briefly as a movie studio extra, encountering famous actors. He became familiar with flamboyant Hollywood celebrities like movie actor George Raft, a big star in the gangster films and a jazz hound. He recalls prominent local boxer Gorilla Jones strolling down Central Avenue with his lion cub on a leash. And character actor Stepin Fetchit “was always raisin’ hell on Central Avenue. Sometimes he’d go to work at the studios in five different Cadillacs like a big parade, right down Central Avenue.”

All that ambient sartorial grandeur rubbed off on Buck: “We would put on our latest clothes and get sharp as a tack and meet on corners of Central Avenue and try to out-dress each other.” He became legendary among his peers as one of the best-dressed cats of Jazz.

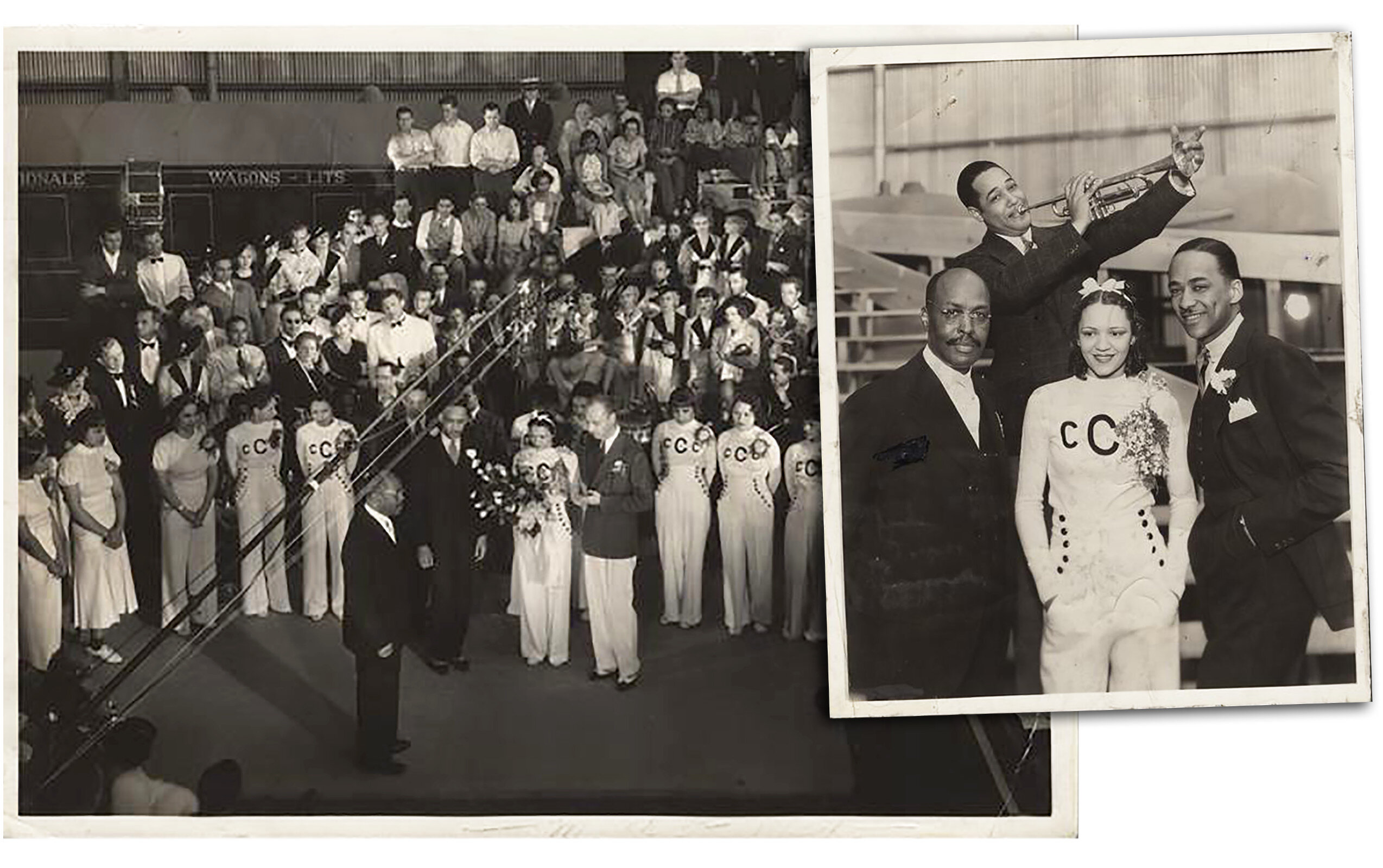

Duke Ellington and his Famous Orchestra visited Hollywood in 1934 filming the motion picture Murder at the Vanities. Becoming friendly with Ellington, Buck worked briefly for Duke who ‘surprised’ him by hosting a celebrity-studded wedding.

A grand affair, the Clayton nuptials took place at the Paramount film studios in Hollywood, the Reverend Napoleon P. Greggs officiating. A special stage with raised seating was packed with attending luminaries including actors Mae West and George Raft while the newsreel cameras whirred.

Duke’s orchestra performed for the ceremony and reception, “Ivie Anderson sang,” reminisces Clayton, “Duke did a concert of numbers . . . Cootie [Williams] and Tricky Sam Nanton growled the wedding march.” Two weeks later the newlyweds were on a slow boat to China, a voyage of 44-days via Hawaii and Japan.

Shanghai, China 1934-35

“I still say today that the two years I spent in China were the happiest two years of my life . . . My life seemed to begin in Shanghai. We were recognized for a change and treated with so much respect.”

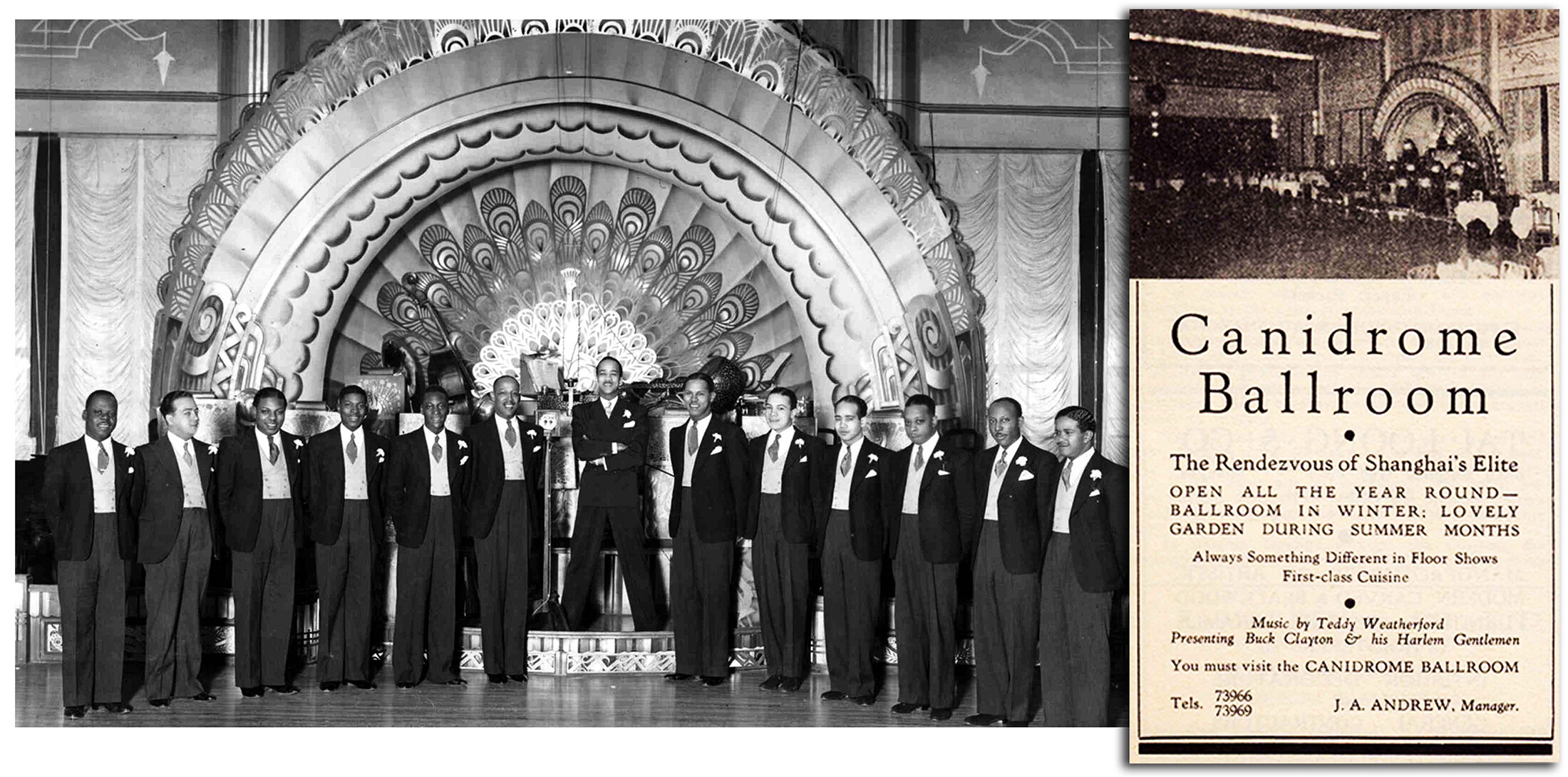

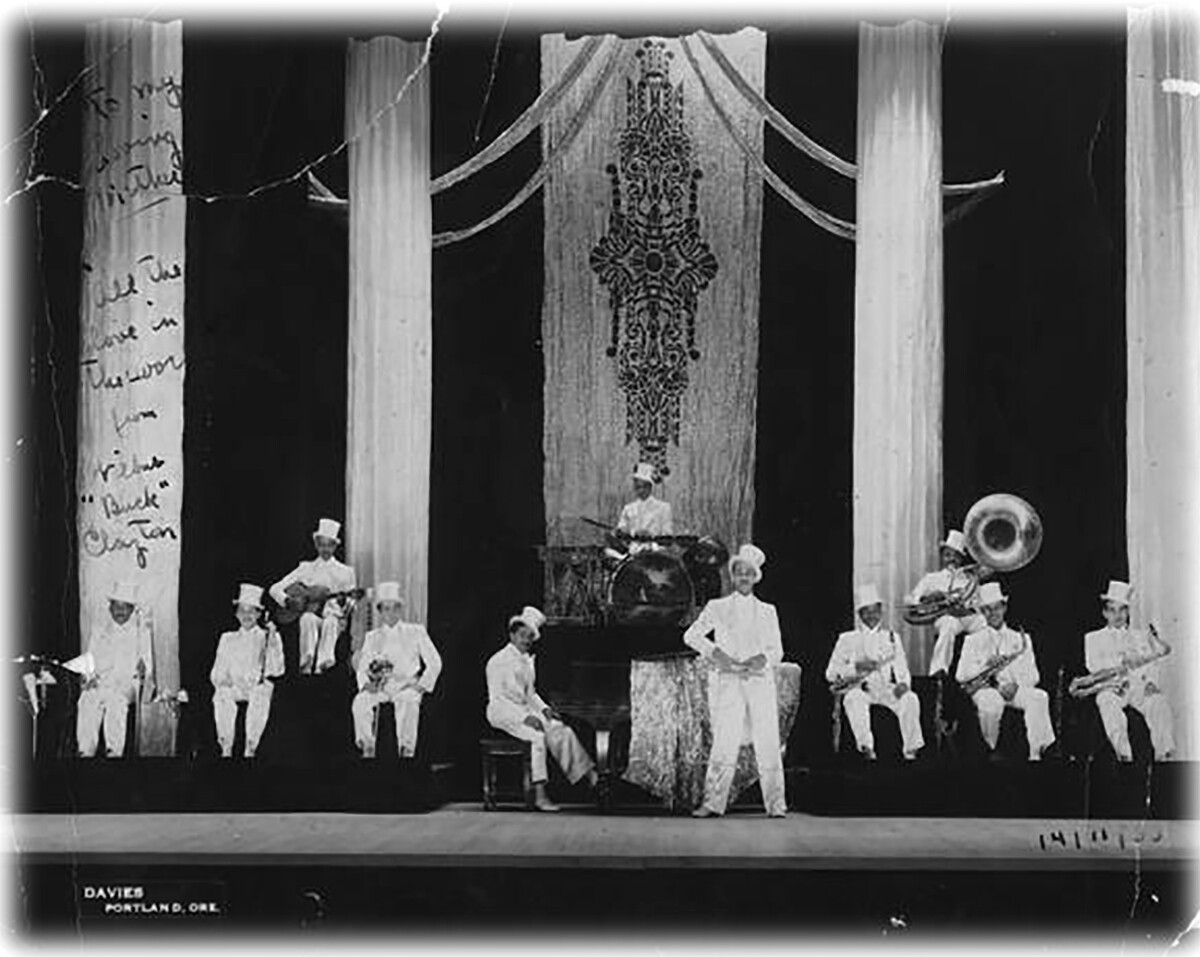

The Harlem Gentlemen, Clayton’s 12-piece ensemble went to Shanghai accompanying pianist Teddy Weatherford: “The personnel of the band was Teddy Buckner, Jack Bratton, myself (trumpets), Happy Johnson, Duke Upshaw (trombones), Eddie Beal (piano), Baby Lewis (drums), Frank Palsey (guitar), Reginald Jones (bass) and Joe McCutchin (violin).”

The musicians were warmly welcomed with ceremonies and a grand banquet and outfitted with dozens of tailormade custom band uniforms and suits. Provided private lodgings with servants and cooks, they went horseback riding “almost every week,” though Buck took more than one bad spill from the excitable former racehorses.

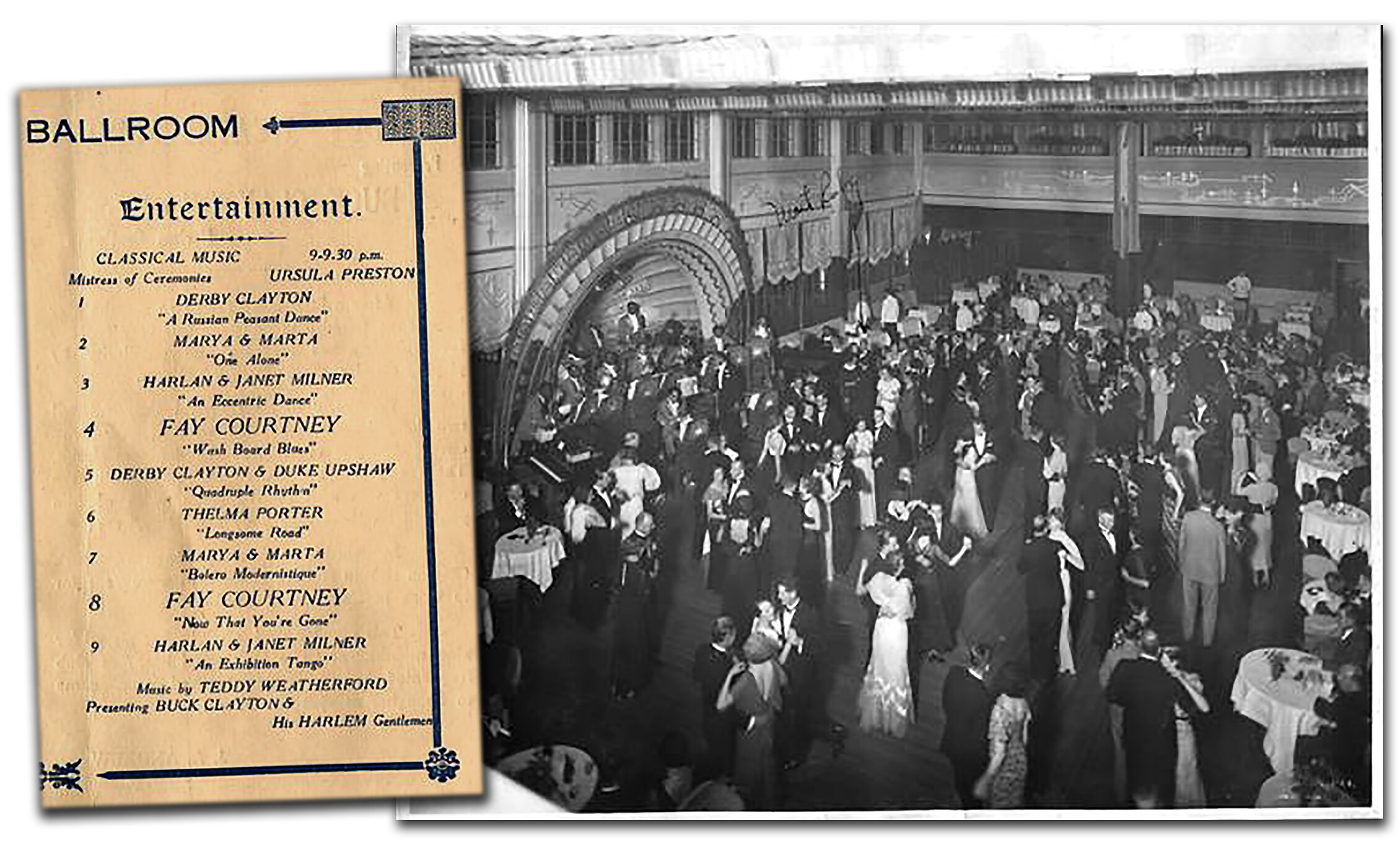

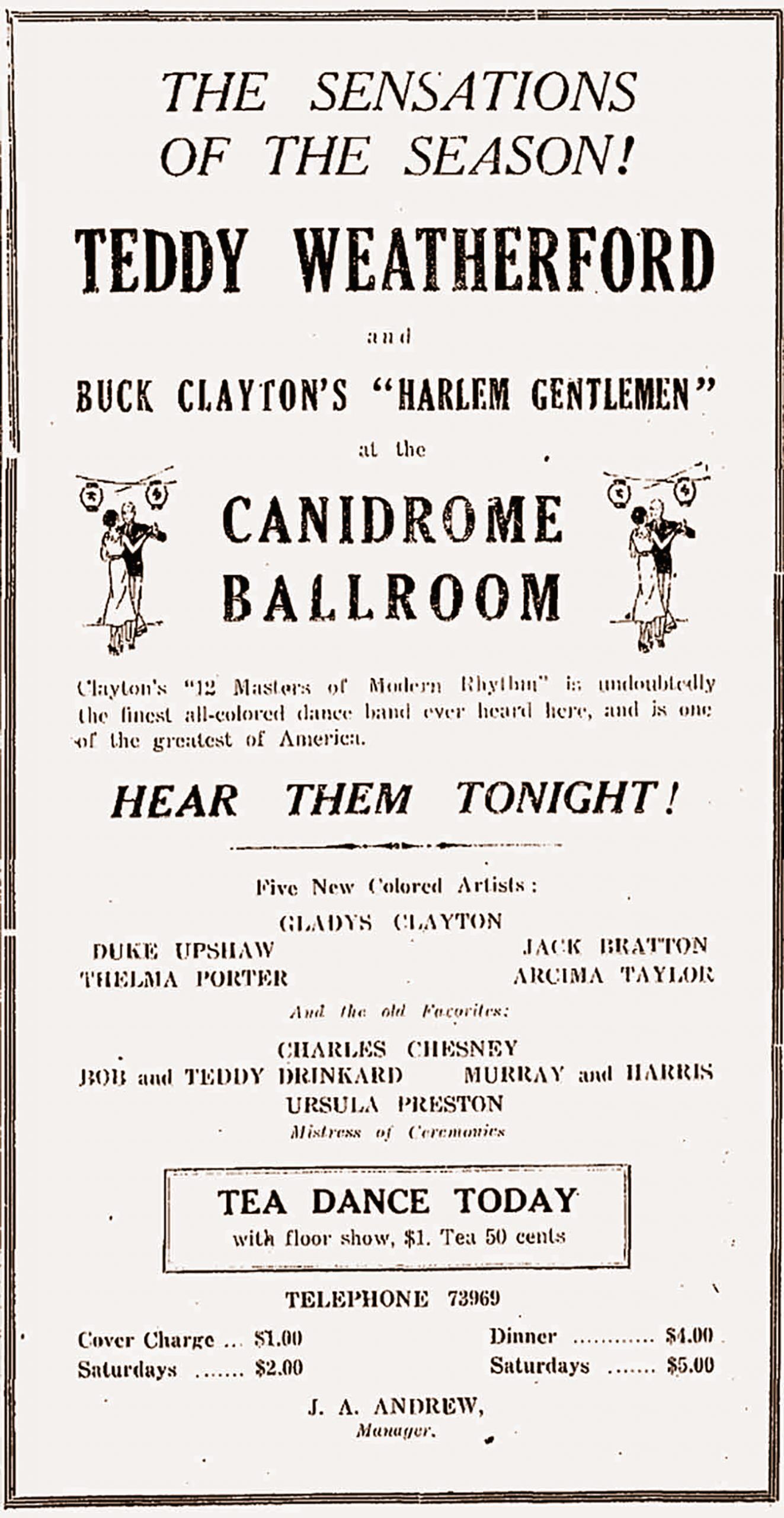

“There were other clubs in Shanghai, but the Canidrome Ballroom topped them all.” The opulent entertainment complex was a sprawling compound of nightclubs, casinos, bars and bungalows situated at a swank dog-racing course. Clayton and his orchestra were featured in the grand ballroom:

“We found the ballroom to be in a huge white building that must have covered several acres of land – spacious grounds that included several green lawns where the tea dances were held. In the back of the huge building there was a greyhound racecourse where every night there would be racing. The word ‘Canidrome’ means in some way ‘dog racing.’ I don’t believe that the whole time . . . I was in every gambling room in the building as there was so many.”

Opening at the Canidrome

Opening night was “fantastic” he writes. In attendance were Madame Chiang Kai-Shek — wife of the President/Chairman/Generalissimo — and her sister “who insisted on learning tap-dancing from my trombonist, [taking] lessons from him every Saturday afternoon for a while.”

They drew the local elite of English, French, Russian and Japanese expatiates resident in Shanghai:

“We started off the evening with classical music from nine o’clock to nine-thirty and after that it was back to Harlem. The menu was just unbelievable. There was a fourteen-course dinner for four dollars beginning with queen olives, stuffed roast capon and ending with coffee. Just four dollars.

Teddy Weatherford was playing four different nightclubs each night, so he could only play with us on one number before he would have to leave for another club to be in time for his show there . . . but at the end of the week he had four salaries coming to him.”

Teddy Weatherford was playing four different nightclubs each night, so he could only play with us on one number before he would have to leave for another club to be in time for his show there . . . but at the end of the week he had four salaries coming to him.”

Their big production numbers were “Rhapsody in Blue,” with pianist Weatherford the featured soloist, and Ravel’s “Bolero” which Buck loved directing. The act included singers and a ballroom dance exhibition by the Mistress of Ceremonies. And Derb Clayton was “asked to perform in the show because of her background at the Cotton Club in Los Angeles.”

Buck and his associates also played for the U.S. Marines stationed in Shanghai, “sometimes we would play for them at their dances and also we would play many benefits for them.” Despite that, he reports several violent fights that were provoked by racist American Marines. These brawls, with “southern crackers” in his words, were serious enough to generate death threats, ending the Canidrome gig.

After the Canidrome

Fortunately, they soon found work at the Casa Nova Ballroom, which included apartments above the club on the topmost floors, “not quite as elegant as the Canidrome, but at least a job where we could prove ourselves.” With only six or seven pieces, “it was better in a way that the other half [of the band] had departed for Los Angeles.”

Too modest by half, Buck fails to mention in his memoir that he collaborated with Chinese maestro and impresario Li Jinhui (1891-1967). Known as “The Father of Chinese Popular Music,” Li assembled the first all-Chinese jazz band. His scores and arrangements were predominant fare in the cabarets, nightclubs and recording studios of Southeastern Asia.

Clayton played a key role shaping Li’s popular style. He dabbled in the local idiom himself: “I sketched out some of the most popular Chinese songs at the time . . . playing it like we had been doing it a long time. It wasn’t too different from our music except the Chinese have a different scale tone.”

Meanwhile, Buck and his associates were becoming increasingly uncomfortable with the aggressive stance of the Japanese military which was brutally occupying much of China. They departed Shanghai just weeks before Japanese naval bombardment commenced, followed by invasion and occupation. Bassist Reginald Jones, who remained in China by choice, had a rough go of it but survived.

Buck Clayton’s Jazz World

Buck Clayton assisted by Nancy Miller Elliott

255 pages, photos, discography and index

Oxford University Press, 1986

Part Two follows Clayton back to the West Coast, the Jazz dives of Kansas City, joining Basie and becoming an international star. The storytelling continues at the JAZZ RHYTHM website: Buck Clayton

Links, Sources and More:

All photos are from University of Missouri-Kansas City

Clayton’s scrapbooks and personal photo collection are archived in the Wilbur “Buck” Clayton Collection donated to LaBudde Special Collections by Clayton’s wife, Patricia.

Swingin’ with Buck Clayton Radio Documentary (Part 1 and Part 2)

Swinging with Trumpeter Buck Clayton, by Dave Radlauer

Central Avenue Sounds: Jazz in Los Angeles, Editorial Committee (University of California Press, 1998)

Buck Clayton and Whitey Smith: Two Tales of Shanghai Jazz

Dave Radlauer is a six-time award-winning radio broadcaster presenting early Jazz since 1982. His vast JAZZ RHYTHM website is a compendium of early jazz history and photos with some 500 hours of exclusive music, broadcasts, interviews and audio rarities.

Radlauer is focused on telling the story of San Francisco Bay Area Revival Jazz. Preserving the memory of local legends, he is compiling, digitizing, interpreting and publishing their personal libraries of music, images, papers and ephemera to be conserved in the Dave Radlauer Jazz Collection at the Stanford University Library archives.