Like many people, I imagine, I first became aware of the term “Creole” in relation to some jazz musicians, such as Jelly Roll Morton, Sidney Bechet, and Kid Ory, among others, who were often termed, or referred to themselves as, “Creoles”; I also became familiar with King Oliver and his Creole Jazz Band. Beyond that my idea was that the term simply meant “being biracial,” although certainly Oliver and most of the band members did not appear to be “biracial.” (It turns out I was only partially correct. Rather than accepting the limited criterion of “biracial,” Vézina opts for “mixed descent” as being more accurate.) And at the same time, I never gave thought to how jazz might have been influenced by the concept.

Like many people, I imagine, I first became aware of the term “Creole” in relation to some jazz musicians, such as Jelly Roll Morton, Sidney Bechet, and Kid Ory, among others, who were often termed, or referred to themselves as, “Creoles”; I also became familiar with King Oliver and his Creole Jazz Band. Beyond that my idea was that the term simply meant “being biracial,” although certainly Oliver and most of the band members did not appear to be “biracial.” (It turns out I was only partially correct. Rather than accepting the limited criterion of “biracial,” Vézina opts for “mixed descent” as being more accurate.) And at the same time, I never gave thought to how jazz might have been influenced by the concept.

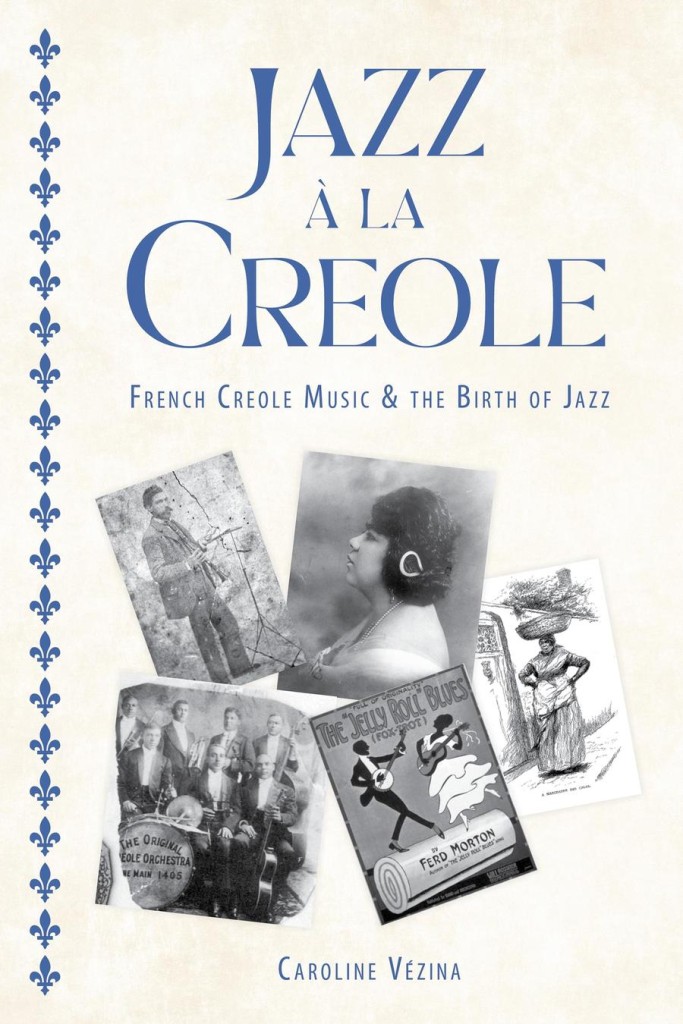

In this book, Jazz à la Creole: French Creole Music & the Birth of Jazz, Caroline Vézina attempts to clarify any misconceptions by presenting the results of a thorough investigation of how jazz was influenced by all things Creole—the music, the musicians, the culture—focusing especially on New Orleans. She begins her research with the turn of the 19th century when Louisiana was still a colony

Initially Creole referred to “people of European parentage born in the colony,” according to one researcher and to “people born in the colony” without reference to color, claimed another. “European” in this case usually meant French or Spanish, most frequently the former. And this criterion was lasting. So we find Jelly Roll Morton keen to flaunt his French heritage as did others, such as Kid Ory. The Creole language that many Creoles spoke was decidedly French in origin as we can see when looking at the lyrics to some of the Creole songs included in the book.

After the end of the Civil War and the Emancipation it engendered, the civil turmoil that resulted was apparent also in the Creole world. Thus we have various subgroups, all trying to hold their place in the hierarchy, particularly since the “one drop rule” (the Code Noir) defined everyone with any Black ancestry, no matter how little or far back in time, as Black. Thus most Creoles fell into that “one drop” category and were desperate to hold on to their cultural superiority, as they saw it. They were educated, appreciated the finer things in life such as classical music, opera, dress, etc. They were schooled musicians: they could read music and most were not eager or happy to become affiliated with Black uptown musicians who could not read and played “ratty” music by ear with lots of improvisation. None of that amounted to anything with the passage of the Jim Crow laws and the segregation they enforced: any Creole with any black ancestry, no matter how little, was Black. Period.

The first part of the book, some 121 pages in length, begins with a short “history” of the development of all things Creole. After this chapter, Vézina goes on to analyze how Black American folk music, plantation songs, and work songs, all part of Creole music, contributed to the development of jazz. In similar fashion she considers other Creole elements, such as French religious music from the ubiquitous Catholic Church in Louisiana along with European music and dance, classical music, even military music and how they found their way into jazz.

The second part of the book considers a number of early jazz Creole musicians, including the Tio family, Jelly Roll Morton, Kid Ory, and Sidney Bechet. Vézina does not mean these to be full biographies, of which there are many, but rather to be brief examinations of how the musicians’ being Creole contributed to the development of jazz from the early period of the 1920s through the revival period of the 1940s. Following that is a chapter on Creole songs and their role in the jazz story. These include such well-known titles as Eh, La Bas and Les Ognons.

Finally, the last parts of the book are devoted to appendices which contain the piano scores and lyrics to a number of French cantiques (religious songs somewhat akin to Protestant hymns), then a section (28 pages) of notes, some substantial, to all of the previous chapters; and lastly a concluding bibliography and select discography.

While the book is not exactly a tome, being only a little over 200 pages total, it is a scholarly work which requires close attention. It is not light reading. Most importantly, it closes, to a great extent, the gap that previously existed in the history of jazz. It is available at Amazon in both the UK and the US.

Jazz à la Creole

French Creole Music and the Birth of Jazz

By Caroline Vézina

Series: American Made Music Series

University Press of Mississippi

www.upress.state.ms.us *248 pages, 1 table;

29 b&w figures; 20 musical examples

Hardcover: 9781496842404, $99.00

Paperback: 9781496842428, $30.00

Born in Dundee, Scotland, Bert Thompson came to the U.S. in 1956. After a two-year stint playing drums with the 101 st Airborne Division Band and making a number of parachute drops, he returned to civilian life in San Francisco, matriculating at San Francisco State University where he earned a B.A. and an M.A. He went on to matriculate at University of Oregon, where he earned a D.A. and a Ph.D., all of his degrees in English. Now retired, he is a professor emeritus of English at City College of San Francisco. He is also a retired traditional jazz drummer, having played with a number of San Francisco Bay Area bands, including And That’s Jazz, Professor Plum’s Jazz, the Jelly Roll Jazz Band, Mission Gold Jazz Band, and the Zenith New Orleans Parade band; he also played with some further afield, including Gremoli (Long Beach, CA) and the Phoenix Jazzers (Vancouver, B.C.) Today he reviews traditional jazz CDs and writes occasional articles for several publications.