Set forth below is the sixty-second “Texas Shout” column. It first appeared in the June 1995 issue of West Coast Rag, now known as The Syncopated Times. The text has not been updated, but the following introductory note was added when this essay was reprinted in July 2003.

Set forth below is the sixty-second “Texas Shout” column. It first appeared in the June 1995 issue of West Coast Rag, now known as The Syncopated Times. The text has not been updated, but the following introductory note was added when this essay was reprinted in July 2003.

This was the last “Texas Shout” to deal exclusively with ragtime. Thus, perhaps a few words about the ragtime scene since June 1995 are in order to supplement the remarks in the column, which are essentially still accurate at this writing.

Everything published during ragtime’s heyday is now in the public domain and may be reprinted free of royalties and other original copyright restrictions. As a result, most well-stocked music stores, and some of the large book store chains, have at least one sizable volume of vintage rags on the shelf.

The availability of the music has encouraged a small number of younger musicians to play ragtime, some of whom are exceptionally talented performers. However, as with the current situation for younger Dixieland players, their friends do not come to see them play at ragtime societies, festivals and concerts.

Thus, though the current ragtime audience is not quite as superannuated, on average, as that for Dixieland jazz, it still consists primarily of older folks and is not getting any larger. There are a number of ragtime societies and weekends dotting the landscape, but most of them are quite small.

The societies, even ones that have been up and running for years, attract so few people to their periodic gatherings that, in most cases, a person can count attendees on his fingers and toes. Some such meetings occur in members’ living rooms.

Ragtime festivals can finish in the black because their acts are typically solo performers, many of whom, as mentioned below, are playing for fees below cost in return for a chance to get together with well-known ragtimers. Still, even the long-running events draw so poorly that to call them “festivals” is a little misleading. The second largest ragtime festival in the U.S. — a profitable weekend well into its second decade which (1) regularly offers a blockbuster lineup of top-name ragtimers, (2) is publicized in every ragtime- oriented publication and (3) is held in one of the nation’s most thickly-populated regions – gets only about 300-400 people to attend each of its three days.

Ragtimers aren’t what they used to be. I’m not saying they’re better or worse, mind you, just different.

I discovered ragtime in the 1950s through two sources. One was the wonderful book They All Played Ragtime. It happened to be on the library shelf of music books through which, as a youngster trying to learn about this music, I was systematically reading my way. I was captivated by the brilliantly told and researched story of what was then America’s completely forgotten popular art form.

The second was the music of Joe “Fingers” Carr (a pseudonym used by pianist Lou Busch for recording ragtime). Carr’s performances were usually of vintage pop tunes played in a two-fisted virtuoso novelty ragtime style with a breezy rhythm accompaniment. They were popular enough to support a string of albums for Capitol during the early LP years and to get occasional radio play – about the only ragtime consistently heard on popular music stations back then.

(Incidentally, the recordings of Carr and other ragtimers of that period, such as Johnny Maddox, are unfairly dismissed by many of today’s ragtimers. This injustice occurs because a major portion of the current ragtime community, for reasons stemming from developments of the early 1970s (discussed below), has been conditioned to accept an incorrect belief – namely that shallow commerciality taints any ragtime performance which deviates much from Missouri Valley/Joplin-style ragtime played per score with a fair amount of academic restraint.)

A lot of ragtimers my age will tell you that these two influences were the ones that started them down the ragtime highway. Unfortunately, it didn’t do us much good. There was no organized ragtime community in those days. Also, the music simply wasn’t available, either in published sheet music form or on record.

If you were a pianist looking for classic rags, you were limited to a couple of commercial folios. The Ragtime Folio, from Melrose Music, contained nine rags from John Stark’s legendary catalog, including works by Joplin, Scott and Lamb. Play Them Rags!, from Mills, contained thirteen pieces – a few Joplins plus a number of Tin Pan Alley rags, some, unfortunately, of no special distinction.

Beyond that pair of collections, you were on your own, sifting through the antique store/auction/flea market circuit, if you had the time and dedication. I didn’t have the time, or indeed much money for sheet music, while in high school and college. Thus, I could have counted on the fingers of one hand the number of additional legitimate ragtime piano solos I’d managed to collect after years of nursing a consuming interest in ragtime.

The same was true of recordings. There were, as mentioned, ragtime LPs of popular standard songs, but no one was recording the rags celebrated in They All Played Ragtime. You could read the book and be tantalized by its descriptions of the delights of “The Easy Winners,” “Efficiency Rag,” “St. Louis Rag,” “Ragtime Nightingale,” etc., but just try to hear them. In fact, I had graduated from college, law school and business school before I even met another person who could play a classic-period ragtime piano solo.

By the 1960s ragtimers had begun trying to find each other. St. Louis’ Trebor Tichenor, a formidable force in ragtime today, was involved with a publication called The Ragtime Review. A bit later, some folks in Toronto established The Ragtime Society, which became the principal focal point for ragtime from the late sixties through most of the seventies.

Not surprisingly, the ragtimers who gathered in Toronto for the Society’s annual Bash were primarily historically oriented. Because we had little first-hand exposure to the idiom, we were spending much of our time simply trying to find the old pieces, to understand what they were all about and what kind of people wrote them. We were sheet music and record collectors.

Few of us were composers. Except for Trebor and the late Tom Shea – and of course, Eubie Blake, a pioneer who never stopped composing – virtually no one was writing much new ragtime.

Then through an incredible series of coincidences, a marvelous thing happened, something beyond our wildest expectations. In the early 1970s, three completely independent projects focusing on Scott Joplin came to fruition: (1) The New York Public Library financed the first publication of Joplin’s collected works. (2) A college in Georgia sponsored the first full-scale public production of Joplin’s opera “Treemonisha.” (3) Joshua Rifkin, a young pianist, recorded an LP of Joplin’s rags, played with proper academic attention to the scores, for the classical Nonesuch label; as a result of a rave notice by The New York Times’ classical reviewer, the album shot to the top of the classical charts.

These developments had two beneficial effects. The legitimate musical establishment began focusing on ragtime, principally Joplin’s oeuvre. The general music market became alert to the possibility that, at least for the time being, there appeared to be the chance to make money out of ragtime.

One of the New York Public Library volumes – the one with all the rags – was published in a soft cover version for sale in music stores throughout the country. Classical pianists began trying to duplicate Rifkin’s success by recording Joplin.

(By the way, playing ragtime accurately per score is no great trick for a classically trained pianist. While there are many technically demanding rags, quite a bit of quality ragtime, including several Joplin works, isn’t particularly difficult. Ragtime, which came along before commercial radio and at a time when few people had many records, couldn’t have become as popular as it did unless the published music was within the grasp of the average parlor pianist of the day.)

These two flurries of interest in Joplin led to an even more unbelievable break for ragtime. Arranger Marvin Hamlisch was commissioned to adapt Joplin’s music for the sound track for a major Hollywood film.

If the film had been a flop, believe me, today’s ragtime scene would probably be very different from the way it is. How, I don’t know, but there can be no dispute that the shock waves from this film still reverberate through ragtime today.

As everybody knows, the movie turned out to be a winner in every way. The Sting(1973) won seven Oscars, including Best Picture. Hamlisch’s single of Joplin’s rag “The Entertainer” (which became popularly known as “The Sting”) rose to the top of the hit parade, the last piece of ragtime to occupy that exalted position.

[As a side note, the ragtime/jazz community has the perverse propensity to bemoan the fact that its music isn’t commercially popular and then berate any jazz or ragtime artist who becomes popular as having “sold out” and “gone commercial.” Thus, it became de rigueur in some ragtime circles to disparage Marvin Hamlisch as having perpetrated some kind of evil pollution upon Joplin’s pristine art.

The fact is that Hamlisch was commissioned to rework Joplin’s music for the film using the format of Gunther Schuller’s 1973 Red Back Book LP for the Angel label by The New England Conservatory Ragtime Ensemble. Had he not taken the assignment, it would have gone to someone else, someone who is unlikely to have equalled the splendid job Hamlisch did (as the film’s sound track LP demonstrates).

Hamlisch’s music is faithful to the period scoring and to the spirit of Joplin’s inspiration while adding immeasurably to the flow of the movie. Who can forget, for example, the evocative way the solo piano playing the closing strains of “Solace” brings out the longing in the film’s “love” scene (remember, nothing in this story turns out to be what it seems at first).

Further, on Oscar night in 1974, when Marvin Hamlisch first stepped up to the podium to accept an Academy Award for his work, he made sure to use a few seconds of his very limited time to pay specific tribute to Scott Joplin. Watching the show live, I thought that was a very high-class un-Hollywood-like thing for him to do. I have never seen Hamlisch given any credit for this generous statement, heard worldwide, by anyone in the ragtime community.

At any rate, Marvin Hamlisch’s work wound up providing ragtime with a public visibility for which it could never otherwise realistically have hoped. The ragtime community owes him a debt of gratitude. It’s high time somebody stood up and said so.]

For a short time, the country was ragtime crazy. The boom didn’t last, but it did leave behind some lasting benefits for ragtime.

First, it brought a lot of vintage ragtime back into print. Major publishers combed their files for material to gather into folios that appeared on music counters everywhere. Except for ones dealing with Joplin, they sold very poorly and were not maintained in the catalog. However, for a short time, literally hundreds of rags, in nearly all of the vintage ragtime styles, could be picked up for a song at your nearest music store.

Dover Publications, a New York book publisher specializing in reprinting material no longer under copyright, is the only one that has kept its ragtime on the market. Through Dover, as of this writing, one can own over 200 turn-of-the-century rags, including all of Joplin’s and most of Scott’s and Lamb’s. The collections concentrate on Missouri Valley and early folk rags, but taken together, Dover’s folios contain more rags than most professional ragtimers have at their fingertips.

Second, as mentioned, the “legitimate” musical establishment’s attention was caught by ragtime during the 1970s boom. Some portion of it still spends time on ragtime. Professional concert pianists occasionally include rags in their recitals, almost always Scott Joplin’s and often as encores or throwaways, but the rags are there. Conservatory-trained pianists are showing up on the ragtime circuit, something that almost never happened prior to The Sting.

Third, the publicity showered on ragtime coaxed some composers out of the woodwork, a trend that has lasted to the present day. As in the past, today’s compositions range from brilliant to execrable. Many are hopelessly derivative of Joplin and other Missouri Valley composers. Some, proclaimed by their composers to be rags, aren’t at all, consisting of a few ragtime syncopations stuck into the middle of arch-modern licks.

Even so, this is a positive thing for ragtime. The music will become a museum piece unless there are people willing to write new works in the idiom.

Ragtimers can only rejoice in these developments. We hoped for years to have ragtime taken seriously by “serious” musicians, and now it is, though perhaps not to the extent we’d have desired. Similarly, we longed for the day when neighborhood music stores would again carry ragtime on their shelves, and now they do. However, like most of life, these uppers are not entirely without their down sides.

There isn’t much point in discussing the negatives at length because ragtime has now become so pervasively a hobby music. There is virtually no one left making a full-time living exclusively from ragtime. Even major ragtime weekends depend to a significant extent on the willingness of featured artists to perform without pay or at less than out-of-pocket cost.

In these circumstances, where economic viability is frequently a secondary or irrelevant factor, the community inevitably is going to drift in whatever directions the whims of the relatively few movers and shakers in the field dictate, regardless of what commentators may write. Sad to relate, nothing anyone says about the scene makes much difference anymore.

Let me just briefly note, then, that I believe a disproportionate emphasis has been given to Scott Joplin since The Sting, even though he is unquestionably ragtime’s all-time greatest composer. For example, most record stores, if they have any ragtime at all, have ragtime browsers devoted almost exclusively to Joplin. Someone who only casually comes into contact with the music could easily be misled into believing that worthwhile ragtime pretty much begins and ends with Scott Joplin’s compositions.

Nevertheless, as true ragtimers recognize, Joplinesque Missouri Valley classic ragtime is not the only ragtime style. Even within that style, (1) both Scott and Lamb produced quite a few rags that are in every way the equal of Joplin’s finest and (2) other ragtime-era composers, though perhaps not as prolific or consistent, left us a wealth of ragtime that is also comparable in quality to top-rank Joplin.

Further, the emphasis on Joplin encourages the already-existing tendency of the ragtime community to focus on ragtime piano solos while regarding ragtime songs and other ragtime compositions as of secondary interest. However, as Ed Berlin points out in his excellent book Ragtime: A Musical And Cultural History,”… songs were the most conspicuous species of ragtime ….” In addition, ragtime was commonly composed for all musical formats, from solo xylophone to full concert band.

It also disturbs me that so many ragtimers who’ve come to the music since 1973 have little knowledge of or interest in the artists who were keeping it alive during the 1950s and 1960s. Quite a few of these pre-“Sting” revivalists are still around and capable of providing quality entertainment at ragtime weekends.

Lastly, I regret that ragtime functions, like Dixieland festivals, are now being invaded to a significant extent by non-genre music, that is, music which isn’t ragtime. I understand why this change is occurring (see, e.g., “Texas Shout” for April 1990). However, I don’t happen to live near any ragtimers, and when I go to a ragtime festival, I’m dying to hear ragtime, not light classics, Latin numbers, etc.

Anyway, ragtimers aren’t what they used to be. I guess that’s to be expected.

However, ragtime itself never changes. We can haul Charles Hunter’s “Just Ask Me” from 1902, Charlie Straight’s “Hot Hands” from 1916, Billy Mayerl’s “Virginia Creeper” from 1925, Joe “Fingers” Carr’s “Rapscallion Rag” from 1952, Max Morath’s “One For Amelia” from 1964, David Thomas Roberts’ “Roberto Clemente” from 1979 and all of the others off our shelves, depress the notes exactly as these fine composers set them down for us years ago, and experience the same uplifting experience that captivated audiences when these works appeared. I suppose that’s what really counts after all.

Want to read ahead? Buy the book!

Want to read ahead? Buy the book!

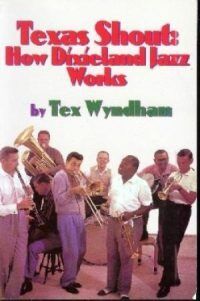

The full run of “Texas Shout” has been collected into a lavishly illustrated trade paperback entitled Texas Shout: How Dixieland Jazz Works. This book is available @ $20.00 plus $2.95 shipping from Tex Wyndham, On request, Tex will autograph the book and add a personalized note (be sure to tell him to whom the note should be addressed).

Tex Wyndham’s 3 CD Guide to Dixieland with music and commentary is available for $20 plus $2.95 shipping. The separate CD, A History of Ragtime: Tex Wyndham Live At Santa Rosa, is available for $13.00 plus $2.00 shipping. On request, Tex will autograph the inner sleeve and add a personalized note (be sure to tell him to whom the note should be addressed).

Send payment to Tex Wyndham, P.O. Box 831, Mendenhall, PA 19357, Phone (610) 388-6330.

Note: All links, pictures, videos or graphics accompanying the Shouts were added at the discretion of the Syncopated Times editorial staff. They did not accompany the original columns and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of Tex Wyndham.

From roughly 1970-2010, Tex Wyndham was: (1) one of the best-known revivalist Dixieland jazz musicians in the US, as cornetist, pianist and bandleader, (2) one of the best-known ragtime pianists in the US, and (3) one of the most respected critics in the US of Dixieland jazz, ragtime, and related music. He is the only person about whom all three of those statements can be made.