Any seasoned record collector is likely aware of the baritone Steve Porter. He was a main fixture of the famous American Quartet, and a common voice on many a minstrel record in the acoustic era, but his career was much more varied than these roles. He got his start as a minor engineer and friend of the burgeoning phonograph crowd, and lasted well into the electric era.

Stephen Carl Porter came from a moneyed past. His father S. B. Porter was a powerful attorney in the Buffalo, New York, area. The family lived comfortably in Buffalo until about the end of the 1880s or early 1890s, when Steve was summoned out to Colorado to help work on telegraphs there. A common background among the earliest recording engineers was that of the telegraph. It was the only technology at the time that could be considered similar to that of the newly emerging phonograph. While out west, Steve met a woman named Emma Fanchon, and the two decided to get married in 1890. By 1894, they were back in New York, this time in the big city.

Around 1895, Steve started to get involved with that eccentric phonograph crowd. It is not known exactly how they found him, but his substantial wealth may have helped. He was a very cultured man, wearing flashy bright ties, ambitiously styling his blond hair, and occasionally sporting more ar

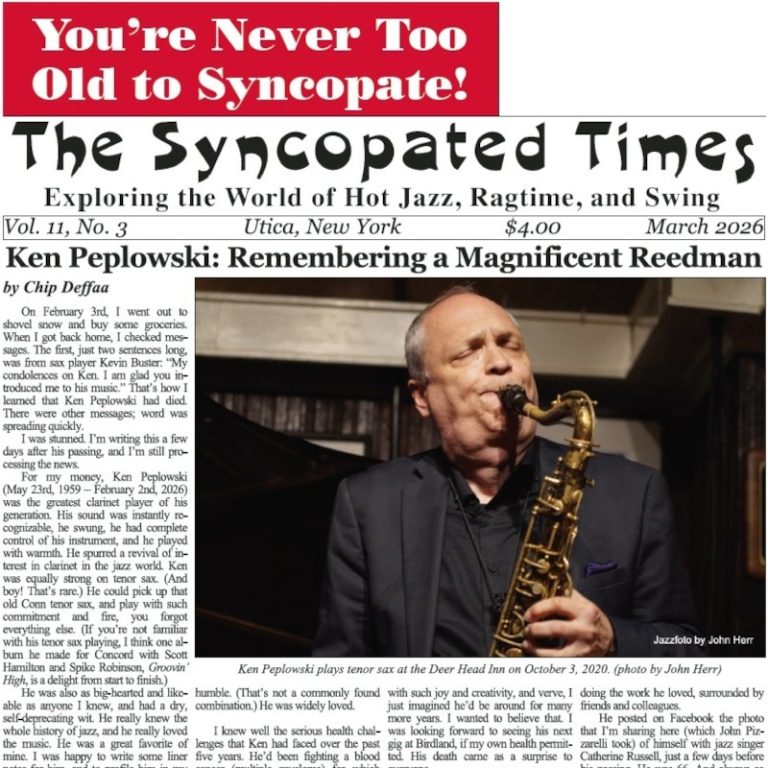

You've read three articles this month! That makes you one of a rare breed, the true jazz fan!

The Syncopated Times is a monthly publication covering traditional jazz, ragtime and swing. We have the best historic content anywhere, and are the only American publication covering artists and bands currently playing Hot Jazz, Vintage Swing, or Ragtime. Our writers are legends themselves, paid to bring you the best coverage possible. Advertising will never be enough to keep these stories coming, we need your SUBSCRIPTION. Get unlimited access for $30 a year or $50 for two.

Not ready to pay for jazz yet? Register a Free Account for two weeks of unlimited access without nags or pop ups.

Already Registered? Log In

If you shouldn't be seeing this because you already logged in try refreshing the page.