Soon we’ll come to the end of life’s journey,

And perhaps we’ll never meet anymore;

Till we gather in Heaven’s bright city,

Far away on that beautiful shore.

If we never meet again this side of Heaven,

As we struggle through this world and its strife;

There’s another meeting place somewhere in Heaven,

By the side of the river of life.

Where the charming roses bloom forever,

And where separation comes no more;

If we never meet again this side of Heaven,

I will meet you on that beautiful shore.

Excerpt from “If We Never Meet Again (This Side of Heaven),” words and music by Albert E. Brumley

Leon Redbone—the ageless guitarist, vocalist, vaudevillian, and time traveler who, by his own account, was writing songs in the early 1900s—has left the galaxy. On the day of his final road trip, the following appeared on his website: “It is with heavy hearts we announce that early this morning, May 30th, 2019, Leon Redbone crossed the delta for that beautiful shore at the age of 127.”

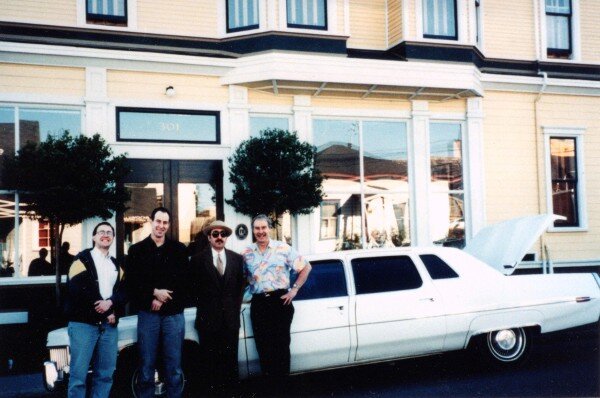

I was 24 in 1990 when I did my first tour with the man whose picture should appear in the dictionary under the word “enigma.” He was the iconic and laconic man-of-mystery in the hat and dark glasses—an image and character he’d created and cultivated to perfection. His debut album, released in 1975, was called—ironically—“On the Track.” His fans thought he was in his 80s or even 90s. In actuality, he was 40 at the time I joined his band. But in those pre-Wikipedia days, so thoroughly convincing was his character, so airtight were his alibis, that he had them all fooled. But unlike Mike Myers’ “Austin Powers,” Paul Reubens’ “Pee-wee Herman,” Sacha Baron Cohen’s “Borat,” and other characters who were left at the office when their creators went home for the day, Leon Redbone was Leon Redbone onstage and offstage. I never saw him without a hat and dark glasses.

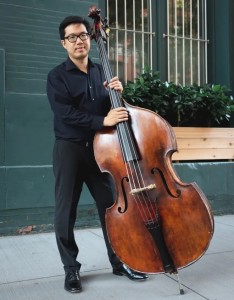

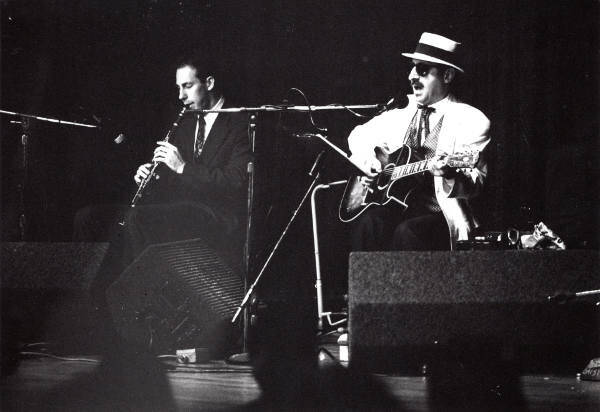

The musicians in his band were there to provide what he referred to as “incidental accompaniment.” I accompanied him on clarinet over a period of 25 years, beginning in 1990 and ending with his final recording sessions in 2015. Between 1996 and 2002, pianist Tom Roberts and I were the sole members of his touring “orchestra,” as he liked to call it, although the band was augmented with other musicians if the budget and the geography permitted.

An incomplete list of the world-class musicians who accompanied Redbone on recordings and/or live performances over the years, some quite extensively, includes Vince Giordano (who worked with him from c. 1981 to 2015 and whose 11-piece Nighthawks backed him up on several albums), Ken Peplowski, Bobby Gordon, Peter Ecklund, Jon-Erik Kellso, Tom Roberts, Paul Asaro, Brian Nalepka, Arnie Kinsella, Joe Muranyi, Yusef Lateef, Phil Bodner, Eddie Barefield, Lenny Pickett, Ed Polcer, Joe Wilder, Mike Davis, Vic Dickenson, Dan Barrett, Tom Artin, Herb Gardner, Andy Stein, Joe Venuti, Terry Waldo, Dr. John, Sammy Price, Mark Shane, Cindy Cashdollar, Leon McAuliffe, Béla Fleck, Eddy Davis, Howard Alden, Birelli Lagrene, Milt Hinton, Jay Leonhart, Giampaolo Biagi, Grady Tate, and Jo Jones.

Despite the predominance of jazz musicians and skillful improvisers in his bands, Redbone didn’t seem interested in hearing a lot of improvised solos. He enjoyed hearing the melody, especially on the slower numbers. Clarinetist Bobby Gordon, who accompanied Redbone for many years before I did, had a gift for playing melodies simply and expressively, and when I joined the band I tried to emulate Bobby. Through my work alongside Redbone, I grew to appreciate and embrace the unpretentious beauty of the melody, and most of my solos were simple interpretations of the melodies.

20, 1990 (first show with LR) (photographer unknown)

I’ll unabashedly admit that I was quite intimidated by him in the beginning. Like the public, I couldn’t figure him out, and never being able to see his eyes didn’t help. He didn’t do much to put me at ease, either. During the long hours we spent in his van driving from town to town during that first tour, he rarely spoke to me. I listened to tapes of his recordings and wrote out the simple arrangements and “road maps” for myself. He sat in the front passenger seat and I sat just behind him. On the second day of the tour, he turned around and sternly asked, “What are you doing?”

I felt my heart racing. I could barely get the words out. “I’m, um, writing out your arrangements.”

He seemed mystified and even annoyed by my reply. “Writing out my arrangements?”

“Yes.”

“What are you writing them out from?”

“Um, the tapes your manager sent me.”

He stared at me through his dark glasses for an awkward moment, then turned back around. I saw a smile come across his face as he leaned back in his seat, and I heard him mutter, “Excellent.”

That first tour and the trepidation within me culminated with an appearance at a jazz festival in Wichita, Kansas, where we went on right before Buddy DeFranco.

His manager and his fans called him “Leon.” The road manager on those first tours—Jake West, from Chapel Hill, North Carolina—called him “Reb-bown.” But he told me he didn’t like being called either “Leon” or “Redbone.” “So what should I call you?” I asked politely, during one of our first encounters. He pondered the question for a moment and then replied majestically, unsmiling, as he raised one eyebrow above the rim of his glasses: “Your Eminence.”

He wasn’t being smug, sarcastic or snobbish; he was just being him. So from that moment until the last time I saw him, 26 years later, that’s how I addressed him. I played it up and he ate it up. Sometimes, when I would greet him at the beginning of a tour, I would genuflect, throwing myself down on the ground at his feet, to which he would usually respond, “Lower.” He called me “Danley,” onstage and offstage—a play on Oliver Hardy’s moniker for his comedic partner, Stan Laurel, a character I channeled during our onstage banter.

Redbone’s music incorporated influences from a vast array of genres, including ragtime, early jazz, blues, country, folk, Americana, opera, Hungarian gypsy music, and more. He had a particular fondness for “sentimental numbers.” Most of his repertoire came from the early days of Tin Pan Alley—the late 1800s through the early 1900s. And where did the record stores, back in day, choose to put his albums? In rock. He should have had his own section—if ever there was an artist whose music was unclassifiable, it was Leon Redbone.

Our performances weren’t “concerts”; they were more like vaudeville shows. The music was, itself, “incidental” to the overall performance. While members of the audience unfamiliar with Redbone, thinking they were going to a concert, might grow impatient watching him spend five minutes tuning his guitar and then taking a sip of his drink, his people—the ones who knew what he was about—would sit, transfixed, for what seemed an eternity, hanging on his every word, his every move, and reacting to the slightest change in his facial expression. Sometimes he’d just raise an eyebrow behind his glasses, and somehow everyone would catch it—even the people in the back row. He’d strike a guitar string and look at the needle on the electronic tuner on the table to his left. If the string was flat, he’d shout “Rise, Lazarus!,” and slowly and deliberately turn the tuning peg in the appropriate direction; if it was sharp, he’d exclaim “Kneel, heathen!”

When he was finished tuning his guitar, he’d pick up the glass on the table, which was filled with Jägermeister, look at the contents and say, “You people really ought to do something about the water in this town.” He’d take a sip, slowly and deliberately, as before, and then strike his strings with his right hand while moving his glass over the strings of the neck with his left hand to create a slide guitar effect. As he did that, he’d say, “Greetings from Don Ho. That man sure knows how to relax.” Every move he made, every word he spoke, was perfectly and expertly calculated. It was a beautiful thing to watch.

Redbone was a Zen master of understatement and comedic timing. I learned a great deal from observing him. He incorporated a series of comic routines into his shows, which were inspired by the original vaudevillians. After a virtuosic solo piano feature by Tom Roberts, for example, Redbone would say, “You know, I was going to play that myself, but I haven’t been feeling well lately. I haven’t felt well for eight or nine days—almost a week.”

That was my cue to become his straight man. I’d say, “Did you go to that doctor I sent you to?”

“I did, but he didn’t do me a bit o’ good.”

“What did he tell you to do?”

“You know, that man, he told me to drink liquor one hour before going to bed.”

“Drink liquor one hour before going to bed?”

“That’s what I said.”

“Well, did you do it?”

“I tried for 45 minutes, but I couldn’t hold any more. And you know what else he told me to do?”

“No. What else did he tell you to do?”

“He told me to take one pill three times a day. But you know you can’t do that.”

“What about that specialist I sent you to?”

“Yeah, I went to him. That man knew what I had goin’ in and comin’ out.”

“What did you have comin’ out?”

“Comin’ out I didn’t have a thing.”

“What did you have goin’ in?”

“I had fifty-two dollars.”

At some point during the show, he’d place his hand, palm down and fingers outstretched, on the clipboard in front of him that held his lyrics. That was my cue for another setup: “Say, who was that lady I saw you walking down the street with last night?”

“That was no street—that was an alley. Besides which, she came up to me. She said ‘Gimme fifty dollars—I’ll do anything you want.’”

“What did you do?”

“Well, I gave her the fifty dollars!”

“What did she do?”

“She’s painting my house.”

People would occasionally ask me if I got tired of playing the same songs every night. Despite doing the same routines and playing—with some variation—the same songs at every show, it never got old and I was never bored. In fact, no two shows were ever the same. How is that possible? That was part of Redbone’s genius. It took me years to figure out that he didn’t like it when things went right during a show. We’d play what seemed to me to be a perfect show—all the music and routines worked without a hitch. We’d get offstage and he’d say something like, “What was the matter with you tonight? Did you have a stroke?”

Other nights, nothing would seem to be going right for me, and he’d walk offstage telling me how great I’d sounded. I don’t think he ever intentionally derailed the train, but he really did seem to enjoy when it went off the track.

Barnes)

The “Danley” character I developed for our shows was emotionless and expressionless. I sat immediately to his right. He’d be doing his shtick, but I’d continue looking straight ahead and not reacting. He’d occasionally look over at me, but I didn’t look back at him. That always got a laugh. It worked well up to a point. It seemed that at every show, something wouldn’t go as planned or he’d say something I’d never heard him say before, and I wouldn’t be able to keep it together. I often had tears in my eyes desperately trying to maintain that poker face. In retrospect, I think he must have known where my Achilles heel was.

By way of example, we played a show in Bend, Oregon in January 1997. It was 30 below outside, and Redbone had left all his gear—with the exception of his guitar—in the van overnight. He had a small, battery-operated fan on the table next to him onstage, and he did a bit where he’d turn on the fan, open a bottle of bubbles, take out the wand, and hold it in front of the fan. As he did that, Tom Roberts and I would play a slow, plaintive version of “I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles.” We’d usually only do a couple of choruses. But on this particular night, the bubbles weren’t working. I kept peeking over at the end of each chorus and saw he was having trouble, so we went into another chorus. After we’d played about five choruses, Redbone discreetly leaned over in my direction and whispered, “They’re frozen.”

Another time, Redbone and I played “Diddy Wah Diddy” as the final encore. Tom Roberts wasn’t on that particular show, so it was just Redbone and me—guitar and clarinet. We played that number at some point during every show. The arrangement involved playing a couple of hot instrumental “out-choruses” after his final vocal chorus. On this occasion, Redbone hit the big chord leading into the first of the two out-choruses, and then stopped. That left me playing unaccompanied solo clarinet. I figured he’d somehow forgotten about the two out-choruses, so I kept playing, assuming he’d jump back in at some point. I knew that if I stopped, it would really sound like a mistake. He never came back in. I played the two out-choruses by myself, and then we stood up and walked offstage. “What happened?!” I asked.

“When I hit that chord, my thumb pick got stuck between the sound hole and the string. I knew if I pulled my finger out, the pick would come off and get stuck inside the guitar. So I was trying to get my thumb out without losing the pick.” To the audience, it must have looked like a scene from a Woody Allen film. I was glad I didn’t look over while all that was happening.

During a show in Annapolis, Maryland once, unbeknownst to Tom Roberts and me, Redbone had given his laser pointer to the sound engineer before the show, with specific instructions. At one point, Redbone looked over at Tom and said, “Doesn’t your ex-wife live in this town?” At that moment a red dot appeared on Tom’s forehead.

Despite the tendency at every show for our best-laid plans to go awry, I never felt as though Redbone wasn’t in complete control of the performance in his own subtle way. During the years that Tom Roberts and I were “the orchestra,” I don’t remember a show ever spinning recklessly out of control. Redbone knew precisely how far the antics could go before things needed to be reined in. He once told me, “There’s a line. If you cross it, it’s not funny anymore. It just becomes silly.”

He was constantly bombarded with prying questions from reporters, talk show hosts and fans. In the beginning I worried that he’d be cornered and end up in an awkward position. But I grew to learn that he had this character down. He was armed to the teeth with stock answers to prying questions:

“How old are you?”- “Almost 5000.”

“Is it true you’re from Toronto?”- “I’ve heard that.”

“What’s your favorite kind of music?”- “Silence.”

“Do you speak any other languages?”- “Yes. All languages.”

It was always his interrogators who ended up feeling awkward.

He also had stock phrases he’d insert during interviews and in conversation, which exemplified his sense of humor and irony. One of them was “The mind is a terrible thing.” Invariably, someone in the conversation would completely miss the point and add “to waste, I know.”

Barnes)

While I wouldn’t classify him as a “germophobe,” he was very conscious of how germs are spread, and he took extra precautions to avoid being in contact with them. If somebody in the van sneezed, he’d roll down his window, take out a bottle of Ozium he kept in the glove compartment, and spray it one time. It was a hilarious routine, and in all those years I was with him he never missed. On one occasion, the road manager, Eric Milby—who was driving—sneezed. He, Tom Roberts and I thought Redbone must have been asleep because he didn’t do his thing with the Ozium. He was in the front passenger seat, and we could see from the side that his eyes were closed. We watched and waited. A minute went by. And then we heard the window go down, the glove compartment open, and the familiar “chhhhht.”

photo by Leon Redbone)

Redbone had a Polaroid camera onstage—the kind that had a motor that ejects the photo immediately after the photo is taken, and you watch it develop. At every show, he’d take a Polaroid snapshot of the audience. He’d begin by saying “Uno momento, por favor!” Then he’d pick up the camera, hold it in his right hand, look through the viewfinder, motion with his left hand for the audience to “move in,” press the button, and the photo would be ejected. He’d say, “If this comes out, in a little while I’m going to pass it around, and if you wouldn’t mind signing it for me, I’d appreciate it. I’m looking for a few good audiences to take out on the road with me. Just write your name, address and phone number at the bottom, and draw an arrow across the photo so I’ll know you. But please, please—write small.”

His public thought he was a heavy drinker and a cigar smoker, no doubt because he was always seen drinking during performances and had a “whiskey voice.” In reality, he would fill his glass with Jägermeister an hour before the show and drink during the show, but stop immediately after the show was over. In all the years I worked with him, I never saw him drinking outside of that hour prior to the show and during the show. And I never saw him smoking a cigar or smoking anything at all. In fact, when I was originally interviewed for the job in his band, I was asked if I smoked. He didn’t want a smoker in the band. I’m not sure where the misconception about him being a cigar smoker came from—I suppose that seemed to fit in with the hat-and-glasses look.

Redbone didn’t like to fly. He’d been in a plane crash many years before I met him. So whenever travel didn’t involve crossing a large body of water, he drove. For tours that began in a locale that was more than a reasonable driving distance from our homes, Tom Roberts and I would be flown to the location of the first stop on the tour, Redbone would pick us up at the airport, and we’d travel in the van with him to the other designations on the tour. Then we’d fly home after the last show.

The music Redbone liked to listen to during the long road trips was as diverse as the music he performed: French accordionist Gus Viseur, Irish tenor John McCormack, Hungarian gypsy singer Imre László, comedy duo Moran and Mack, vaudevillian/vocalist Emmett Miller, blues guitarist Blind Blake, clarinetist and contortionist Wilton Crawley, contemporary gypsy jazz guitarist Angelo Debarre, “The Singing Brakeman” and “The Father of Country Music” Jimmie Rodgers, zither player Ernst Naser, 1920s pop vocalists Lee Morse, Gene Austin, and Cliff “Ukulele Ike” Edwards, cornetists Bix Beiderbecke, King Oliver, and Freddie Keppard, Martinique clarinetist Alexandre Stellio, Argentinian tango pianist and bandleader Roberto Firpo, pianist Jelly Roll Morton, Yiddish theater star Aaron Lebedeff, and so many others, spanning a multitude of genres and eras. Some of that music—such as John McCormack—had a profound influence on me and went on to become the soundtrack of my life. Other music—such as his CD of Mongolian throat singing—inspired me to take my own vehicle whenever possible.

Redbone stopped listening to music in the car for a while after he hit a deer while driving, by himself, to a show in Minnesota in the middle of the night. The van was totaled—air bags deployed and everything. At the time of the incident, he was listening to one of his favorite recordings—John McCormack’s performance of “Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair.” He could never listen to that song again without reliving that moment. He told Tom and me that aliens must have dropped the deer on the road, because one minute it wasn’t there and the next it was.

During the years I toured with Redbone, the musical fare for our shows would include selections from the following incomplete list, in no particular order:

“The Ghost of the St. Louis Blues”

“Ain’t Misbehavin’”

“Diddy Wah Diddy”

“When Dixie Stars are Playing Peek-a-boo”

“If We Never Meet Again (This Side of Heaven)”

“Polly Wolly Doodle”

“Clarinet Polka”—my feature

“The Dream Rag”—Tom Roberts’ solo piano feature

“In the Shade of the Old Apple Tree”

“Champagne Charlie”

“Please Don’t Talk About Me When I’m Gone”

“Sweet Sue—Just You”

“Alabama Jubilee”

“Shine On, Harvest Moon”

“My Melancholy Baby”

“My Blue Heaven”

“Love Letters in the Sand”

“Big Time Woman”

“The Sheik of Araby”

“Sweet Mamma (Papa’s Getting Mad)”

“(Mama’s Got a Baby Named) Te Na Na”

“My Good Gal’s Gone Blues”

“It’s a Lonely World”

“Some Sweet Day”

“Another Story, Another Time, Another Place”

“Desert Blues (Big Chief Buffalo Nickel)”

“Some of These Days”

“Think of Me Thinking of You”

“Pretty Baby”

“Crazy Over Dixie”

“I Ain’t Got Nobody”

His spoken introductions to specific songs were as entertaining as the songs themselves. Before playing “Polly Wolly Doodle,” he’d say, “This song’s been around for over a hundred years, so you’ve had plenty of time to learn it. If you know the words, please hum along.” Before “Shine On, Harvest Moon,” he’d say, “This song was introduced to me by Nora Bayes and her husband Jack Norworth in 1907. It was inspired by a performance of Velluti the Castrato, who I heard on a wonderful summer evening in the Vatican in 1848. Let me see if I can imitate just a little bit of him.” He’d make a very faint, high-pitched squealing sound, and then suddenly his voice would drop down to its normal range and he’d say, “He had a high voice.”

NY, September 10, 2015 (photo by Peter Karl)

Redbone’s approach to music was aural and not based on having been formally trained in a conservatory. He learned to do what he did from many years of listening with open ears and an open mind. Occasionally he’d add or drop beats in a measure, but he was very much aware of it. He’d say, “Sometimes the music needs a little more room to breathe.” His band members knew to follow him. When we played “If We Never Meet Again (This Side of Heaven),” it would alternate between a 3/4 meter and a 4/4 meter—some bars would have three beats, some four, and the number of beats in any given bar was different every time we played it. Once I asked him, “Are we doing ’If We Never Meet Again’ in 3/4 or 4/4 tonight?” and he replied, “Are you counting again?!” Most songs were in “the people’s key of B-flat.” Since Redbone tuned his strings a whole step down from standard guitar tuning, that meant he would be playing in the same key as B-flat instruments such as trumpet and clarinet. So when we played in the key of B-flat, he was actually playing in C on his instrument. Those years on the road with His Eminence were memorable and loads of fun. As I was writing about them, I was there again. I could hear his voice speaking every word, singing his songs, and I could hear the unmistakable sound of his guitar. I began to long for one of those “sentimental numbers.” I’d like to think that right now, somewhere, he’s relaxing on a beautiful shore, listening to the strains of “Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair” with his old pals Emmett, Wilton, and Imre…and an extremely forgiving deer.

[Grateful thanks to Tom Roberts for corroborating my stories, reminding me of a few I’d forgotten, and filling in additional details of others. -DL]