As news of festival closings came in a steady drip through December and January I found myself repeatedly assuring people that the sky was not falling—that it is the nature of festivals, even long-established ones, to come and go. I even broke out the old trope about organizations rarely surviving their founding generation.

And of course, that’s right. Festivals are often labors of love and a lifetime’s achievement. Succession planning must be ongoing and even then won’t always work. This is true even when, as is proper, the average festival goer has no idea how much work is being done behind the scenes or who’s doing it.

But what struck me most about the recent closings was that these were still profitable if diminished ventures and attendance, if lower, was still strong. My instincts tell me that where 20,000 people paid for a classic jazz festival in 2017 capitalism will ensure those people have a way to see their choice of music in the future.

More single acts may come through and fill community arts centers. Struggling clubs may find new life as sponsors of monthly events. A restaurant may offer a standing gig, making jazz available year round. Somehow the demand will be met.

Perhaps a new festival will open 40 miles down the road with stages for blues or zydeco or folk music to satisfy a generation with eclectic tastes—tastes that include traditional jazz without being cemented to it.

Along with early “hillbilly” styles and prewar blues, Americana-minded young people now include early jazz in what is collectively referred to as “roots music.” This wasn’t always the case. When I was coming up in the ’90s early jazz was outside the scope of what folk and country blues minded youth were focused on. (The swing revival of that time was something entirely separate.)

Today, people have clearer heads about how fluid the lines were in the ’20s and ’30s. The isolation of genres was in part a creation of the festival culture itself. They sprang up to preserve beloved styles.

The creation of Bluegrass to preserve a string-heavy sound outside the mainstream of commercial country is analogous to the contemporaneous rise of Dixieland as an alternative to commercial, and then academic, jazz. Both the Bluegrass and Dixieland communities held large festivals where like-minded friends could gather and jam beside the OKOM bumper stickers on their RV’s. Both communities have faced turbulent waters recently.

Some of the same forces weakening festivals today are also inspiring a more authentic revival of American musical history. That the upcoming generation recognizes less solid lines of demarcation should be promising, even for purists. It makes early jazz available to a broader array of stellar musicians with a passion for history—and the technical skills to bring it to life. Some are reviving charts not heard in decades, others are creating new compositions in old styles and proving the music is still vital to our culture.

In Lew Shaw’s February essay for this paper, “A Crisis of the Old Order”, he quotes jazz historian William Smith explaining the benefit of house parties this way:

Jazz lovers could hear the music in a comfortable setting rather than in a smoke filled club with folks who often were there for reasons other than the music. Musicians did not have to deal with extraneous noise—like bus boys rattling dishes, since food was not served.

My first reaction was to ruefully note that you could never walk five feet at a Grateful Dead show without hearing someone complain about the people who were there “for reasons other than the music.” It then occurred to me that the proscribed conversations and rattling dishes are just the thing that might draw people out to see a jazz show today.

There was a time in my life when I spent nearly my whole summer shuffling between festivals. These days I would rather see a jazz band at a bar, accompanied by dancing, or at a restaurant, with food, or at a small community arts venue where you can meet the band. The idea of pulling a lawn chair around in the sun or even hiking between indoor venues is of limited appeal. There are many like me, scared off by a 12 hour day of jazz who would welcome an evening of it.

Seeing dozens of shows in a few days also dilutes the experience. You can’t really be giving each group the attention they deserve. When I want to listen intently to an artist I do so at home. When I want to enjoy a group and feel the full effect of their music I seek them out live. Part of that feeling is the setting in which the music is played.

I see the slide in jazz festival attendance as part of a larger cultural shift. It isn’t that festivals as a whole are in decline—in some ways this is the age of the mega-festival, but the people attending Coachella conceive of their experience differently than the two generations who shaped their year around annual attendance at jazz festivals.

Festival going is now an independent experience, the crowd is conquered so that selfies can be taken and shared with the attendee’s “real” community online. Bonnaroo is a destination like the Eiffel tower. The New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival can create this vibe but it is unattainable, and even undesirable, at other traditional jazz events.

What kept two generations coming back to the same festivals year after year, the experience festivals offered, was a sense of community unattainable anywhere else. An exclusivity personified by the term OKOM. There is something special, a sense of family, that develops when you are near people you don’t see every day but share a passion with.

Even ten years ago a show meant bumping into folks you hadn’t heard from since the last show. Now the interest-based communities have all moved online and those in-person interactions have lost some of their punch. “You’ve gotta hear this band” is followed by a YouTube link. It is easier to tell yourself you won’t miss much staying home. The people you used to see only at the festival are now the people you talk to most frequently online, you can even follow them in real time as they share their experience of the festival you are missing.

The same attendance problem is plaguing clubs and civic organizations of all kinds. The Civil War Reenactment community is seeing a radical drop in attendance as the generation who rushed to the hobby after seeing Ken Burn’s Civil War ages out. Even the sesquicentennial wasn’t enough to counter the drop. After nearly 20 years of middle east deployments VFWs are struggling to recruit veterans under 60. The cartoon cliche of a house husband joining his friends at a bowling league is unintelligible to millennials, not because they don’t like bowling, but because joining clubs and leagues is as foreign to them as mailing a letter or subscribing to a print newspaper.

I don’t think this societal shift can be resisted but it can be adapted to. Just as the turn away from cable has sparked a golden age of television, a shift away from festivals might also be a source of artistic inspiration in the traditional jazz community.

Unseen opportunities may yet present themselves. And just like cable hasn’t gone away, festivals aren’t going to either. Some will need to “right size” and in a few specific cases expanding the range of genres may work. Recklessly done, however, that move can be catastrophic.

I think genre expansion is a bad idea except where individual bands bring closely related styles that will appeal to the core festival audience. I’m thinking of New Orleans brass bands, jazzy string bands, and jug bands, but there are other possibilities. Modern Jazz, however, will drown us out. The fans drawn to those styles have fundamentally different tastes.

I believe jazz festivals and events are best segregated by style because a public event is about the crowd. The casual fans that fill seats and make it possible. My sense is that most people have a block of tastes. Traditional jazz fans will have a set of other musical styles they enjoy. Modern Jazz fans will have a separate set of related styles. That is why a prog rock band can fit in fine at a large mainstream jazz festival but would be met with empty seats as the only crossover act at a trad jazz event.

Jazz society membership is a different animal. As that type of civic activity declines it may be necessary for the committed fans of all types of jazz to come together to support the musicians in their regions. These people will have in common the knowledge, commitment, and connections to be a boon to the local jazz scene by helping to arrange gigs for a modern trio at a local coffee shop or a Dixieland band at a concert in the park. Service orientated jazz fans with the time, resources, and skills are too few in number to not work together even if I think the events themselves, for the sake of the audience, should be style specific.

Festivals also need to consider their potential as destinations, events people set goals of attending—and less politely, events people can brag about attending. I think house parties inherently have this going for them and, because of that, there may be room for more of them. In some instances, these can be one time affairs. House parties will also continue to provide the comfortable and music-focused setting many reading this will prefer. Promoters should consider that festivals don’t all need to be annual events. There may be room for a jazz Woodstock every five years to pull people to an under-served region of the country.

Other Trends

Musicians will always find ways to be heard. In the time before radio even an ice cream parlor might try to draw people in with live music. To fill theaters, touring conglomerations came together providing the variety of entertainments known as Vaudeville.

Many feared that radio would be the end of record sales, but live programs allowed bands to reach broader audiences with everything they couldn’t cram into a three-minute side. For a while large clubs and hotel ballrooms dominated. (Those “busboys rattling dishes.”) Then tastes changed, economies changed, theaters stopped featuring live bands at movie premieres. Large clubs became small clubs. Restaurants put in more tables where the band used to sit. Live music slipped farther and farther from everyday life.

The festivals were an adaptation to these realities. They rose up as bands were disbanding, touring alone couldn’t cut it anymore, and standing gigs were becoming less common. They also filled a growing demand for a family-friendly environment to serve middle-aged fans of music that had once been disreputable but was now considered as American as apple pie. The musicians who wanted to play early jazz styles, and the acts that had never stopped playing, had places to share their music—and it worked for decades.

I’m very enthusiastic about the future of Traditional Jazz. It is easier than ever to share this great music, and the changing times provide many opportunities for the phenomenal groups working today. Some economic changes I foresee will bring us closer to the settings in which jazz music first arose and developed. This is great not just for the nostalgic, but for the fan. Hearing a style in its proper setting is hearing it anew. That’s why people go out to shows in the first place.

Driverless cars are poised to radically change a restaurant industry that has already started to boom from the effects of car services like Uber. As trepidation about intoxicated driving wanes restaurants are competing to keep people at their tables, drinks in hand. As they did in the distant past they are turning to live entertainment to draw crowds. This wave has barely started and because it is approachable, and broadly appreciated, classic jazz is uniquely positioned to benefit. A rock rhythm, or a country band, isn’t going to fly at Applebee’s, but even a casual listener will appreciate a competent traditional jazz band. Musicians follow opportunities to play, and more will appear to fill the demand.

The cities are filled by a generation that sees cooking for yourself as a hobby rather than a fact of life. So restaurants in big cities are already noting the live music trend. By 2025 I envision talented musicians from Boise to Louisville will be bouncing around town on a Friday to sit in with as many groups as they can. Not all of this will be great music obviously, but the more milk you have the more cream rises to the top.

As we enter the centennial decade the near future will also feature another inevitable revival of Roaring Twenties fashion and with it an increased interest in early jazz. “Nostalgia” is a touchy word for some people. My take is that young women like to dress up, young men struggle to appear less awkward, and the situation hasn’t changed in a century.

Lindy Hoppers of today are no less fashion-conscious than their great-great-grandparents were and it’s not surprising they would want to accompany the same music with the same clothing. People develop their musical taste by their twenties. Today’s dancers are the committed fans who will be supporting artists thirty years from now. If some people look like they are play-acting that’s one of the best parts of being young.

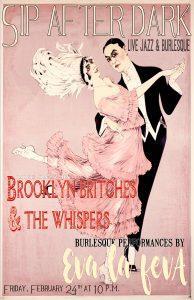

Somewhat farther afield is a strong revival of Vaudevillian performance arts and burlesque shows in the artistic communities of the country. None of the early legends of jazz thought anything of collaborating with comedians and jugglers.

On the local level, such partnerships are starting up again. What I would love to see is a touring company featuring the whole works—from skit acting to dance, accompanied by a band that takes the stage to headline the show. Though it could be, this doesn’t need to be a nostalgia act. A desire exists for live entertainment in a digital world. I think the variety show medium is ripe for a comeback, and jazz bands will still fit in.

Postmodern Jukebox creates vintage parodies of Billboard hits for YouTube. They have leveraged that virality into two separate constantly touring troupes filing theaters of all sizes. Though they don’t play traditional jazz per se they have provided employment for many of the musicians we cover. Their concert success is proof that a Vaudevillian variety show experience could find an audience.

Less obscurely there is a space for the immediate organization of a multi-act limited tour targeting the areas that have recently lost festivals. A one-day event with several headliners and local acts in the afternoon. Other multi-act tours might fill the large beer hall size venues in most cities usually host to small acts with dedicated fan bases. If these are promoted as “mark your calendars” events to the reveling public new fans will be drawn in. There are many casual fans out there waiting to be convinced.

On the East Coast, Prohibition Productions is sponsoring events in the greater New York City area and The Jazz Age Lawn Party concept started by Michael Arenella has now spread to several states and the UK. On the West Coast as other festivals are shutting down Sun Vally Jazz is adding smaller House Party events across several states. What is helping them all is scale and a business focus. National or at least coastal, tour companies specializing in traditional jazz-themed events may be the next step.

Paying Respects

It falls on the younger generations to build the venues of the future for the music we love. We also need to give thanks and credit to the people who have carried the music through to us over the last 70 years. There was heavy lifting involved as anyone who has been awed by encyclopedic discographies made on typewriters can attest.

There were countless unsung heroes behind the scenes- making festivals happen and holding down administrative duties at jazz clubs. These are the people who raised their hand and followed through when something needed to be done, even well aware of the frustrations that come with the territory.

The other realization I had reading Lew Shaw’s article was that the Dixieland Revival and festival era deserves to be documented as the vital part of jazz history that it is. Many important stories are lost because no one thinks they are worth recording at the time. The Dixieland generation hosted many documentarians who have themselves become legends. The eye of history they turned on the early years should now be turned on them and the long middle that followed.

Related Post: A Crisis of the Old Order