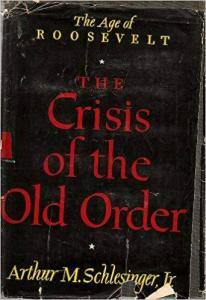

Writing in his The Age of Roosevelt three-volume series, Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. referred to the Depression days of the early 1930s as “the Crisis of the Old Order.” It struck me that the phrase could well be applied to the current state of traditional jazz festivals.

Writing in his The Age of Roosevelt three-volume series, Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. referred to the Depression days of the early 1930s as “the Crisis of the Old Order.” It struck me that the phrase could well be applied to the current state of traditional jazz festivals.

Unhappily for trad jazz fans, a growing number of festivals and jazz parties have recently announced that they will cease operation—some like Sacramento have been around for over 40 years— citing changing demographics and musical tastes, an aging and diminished audience no longer able to travel extensively, escalating costs, inability to attract sufficient sponsor support, and increased competition for the consumer’s time and dollar.

The Sacramento Music Festival, which at one time claimed to be the country’s second largest music festival, is a prime example of the malaise that is impacting trad festivals. Back in the mid-1980s, the Sacramento Dixieland Jazz Jubilee drew up to 100,000 people, and performance venues were spread throughout the city. A popular site was at Cal Expo, a good 20-minute bus ride from the main festival sites in Old Sac. RVers camped in large numbers on the State Fairgrounds, creating a vibrant community for the four-day weekend where social interactions were as important as the music.

Once a not-to-miss event, Sacramento’s attendance has steadily declined since 2002, and this past year, the event attracted only 20,000 fans. According to tax records, the 2002 festival generated $2.7 million in revenue. The year 2010 saw a 50 per cent drop in that number to $1.3 million, with further reductions in 2012 to $681,954, and $425,131 in 2015. In 2014, an appeal to jazz fans and the community to raise $80,000 to balance the annual operating budget brought in $60,000

A Trip Down Memory Lane

Allow me to get nostalgic for a moment and fondly recall the heyday of the so-called West Coast Revival that spanned two generations when Dixieland and Swing held sway, and the number of thriving festivals annually topped 100.

As a writer for this publication (and its predecessors) for 30-plus years, my travel itinerary would regularly include jazz and seafood in Monterey in the early Spring, the Memorial Day weekend in Sacramento, a summer trek to the high altitude of Mammoth Lakes, Labor Day weekend at the Los Angeles Classic, Sun Valley in the Fall with the aspens changing colors, staying home and helping to get the Arizona fest off the ground, Thanksgiving in San Diego, and celebrating the New Year in Indian Wells, California.

A most enjoyable journey, plus one-shot visits to another 30 festivals and parties from Hoboken, New Jersey to Odessa, Texas. All my stories then were generated on-site and in-person. Now I have to rely on the telephone and leads picked up from the Internet and Facebook. Whether you want to look at it as “things never last forever” or “the only constant is change,” let’s take a trip down the trad jazz memory lane for a bit of history.

The Early Festivals

The Newport Jazz Festival which was started by George Wein in Newport, Rhode Island in 1954 is often referred to as the granddaddy of all jazz festivals. However, K.O. Eckland, who compiled a couple editions of Jazz West, tells us that a series of one-day festivals ran for a dozen years as Dixieland Jubilee in Los Angeles between 1948 and 1959. He writes “These memorable events ostensibly were the very first showcases of trad jazz and catered to the public’s demand for ‘showtime jazz’ featuring most of the giants of jazz at one time or another.”

Dixieland at Disney held forth from one to five days in Anaheim from 1962 through 1971, featuring the likes of Louis Armstrong, Dukes of Dixieland, and Bob Crosby’s Bob Cats. The San Francisco Jazz Showcase kicked off in 1972, and the Sacramento Dixieland Jazz Jubilee came along in 1974. (The “Dixieland” reference was dropped in 1992, and the term “Jubilee” changed to “Festival” in 2009. Later it became a “Music Festival” with broad offerings of different genres.) After an aborted start in 1968, Dixieland Monterey got rolling in 1980 as did San Diego. A plethora of festivals, mainly in The West, came into being during the decade of the ’80s, including one in Arizona in which I was involved in organizing.

The bands at these festivals were mostly made up of “weekend warriors,” augmented with occasional all-stars, and had wonderful names: Cats ‘n’ Jammers, Black Dogs, Hot Frogs Jumping Jazz Band, Jazzberry Jam, Night Blooming Jazzmen, Natural Gas, Hot Cotton, Professor Plum, Cell Block 7, Fat Sam, Conrad Janis’s Beverly Hills Unlisted Jazz Band, Cottonmouth D’Arcy Jazz Vipers, K.O. Eckland’s Desolation Jazz Ensemble & Mess Kit Repair Battalion, Firehouse 5 + 2, and Palm Springs Yacht Club, just to recall a few.

Jazz Parties

Jazz parties differ from festivals in that they are held in a single venue, usually a hotel ballroom, while festivals have multiple venues that are sometimes in various locations and require shuttles. Jazz parties involve 15 to 20 all-star musicians who perform in different combinations for each of the 45 to 60-minute set throughout the weekend.

The late Dick Gibson is credited with initiating the jazz party concept, starting in 1963 when he brought a group of musicians he liked together over Labor Day weekend in Colorado. His idea was to break even, bringing two dozen musicians and up to 500 paying guests to places like Vail, Aspen, Colorado Springs and Denver for this yearly reunion. Over the 30 years of Gibson parties (1963-1991), similar events came into being in places like San Diego, Atlanta, Colorado Springs, Wilmington, N.C., Paradise Valley, AZ and Odessa, Texas, even one in England.

Gibson had an interesting background. He played in the 1946 Rose Bowl on an Alabama football team that defeated Southern California. After graduation, he coached at his alma mater and taught creative writing, once having William Faulkner, the famed American writer and Nobel Prize Laureate, as a guest lecturer. He became an expert on Oriental rugs, wrote fiction, worked as an investment banker, and made a fortune forming the Water Pik Company, which he sold in 1967.

In 1962, he became disenchanted with the daily commute to New York City and decided to move his family to Denver. However, he soon found he missed the ocean and the kind of jazz he wanted to hear, the way he wanted to hear it. He told his wife that he could not do anything about the ocean in Colorado, but he could do something about bringing good jazz to the Rocky Mountains.

A New Way to Hear Jazz

Jazz historian William Smith wrote: “This was the genesis of a change in the way fans listened to jazz and the way it was played. Guests were requested to hold conversations to a minimum. ‘Whispering sweet nothings’ was Gibson’s suggestion. Jazz lovers could hear the music in a comfortable setting rather than in a smoke-filled club with folks who often were there for reasons other than the music. Musicians did not have to deal with extraneous noise—like busboys rattling dishes, since food was not served in the ballroom.”

When Gibson passed away in 1998, it was said there were as many as 60 jazz parties in this country and overseas. Currently, the last surviving parties where the emphasis is on classic jazz are held in Del Mar (California), Colorado Springs, Wilmington, North Carolina, and Odessa, Texas.

People have been talking and writing about the demise of festivals and jazz parties for over 20 years, and while these recent announcements may portend the beginning of the end of an era, the beat still goes on in a number of locations around the country, thanks to a handful of survivors that are healthy and vibrant and who continue to keep the music alive by adapting to the times and attracting new fans.

Read a response by TST Associate Editor Joe Bebco: What is to be Done?

Lew Shaw started writing about music as the publicist for the famous Berkshire Music Barn in the 1960s. He joined the West Coast Rag in 1989 and has been a guiding light to this paper through the two name changes since then as we grew to become The Syncopated Times. 47 of his profiles of today's top musicians are collected in Jazz Beat: Notes on Classic Jazz.Volume two, Jazz Beat Encore: More Notes on Classic Jazz contains 43 more! Lew taps his extensive network of connections and friends throughout the traditional jazz world to bring us his Jazz Jottings column every month.