Charles Prince is a domineering character in the world of record collecting. If you see a pile of early records, the chances are pretty good that you’ll see at least one record with his name on the label somewhere. He is all over the place on records, but little has been done in terms of research and biography. There is a lot of misleading and vague information on Prince out there, and this article will attempt to correct the uninformed guesses that have left him an oddly mysterious character.

Charles Adams Prince lived a very old California life, with status in the state that was similar to that of a railroad man’s son. Charles was born around December 1867 in San Francisco, but his family had relocated to the small remote town of Santa Cruz by 1870. Charles’ parents were in the fruit packing business, which was and still is a major California industry. By the mid-1870s, the family had moved back into the big city and there they remained. Prince grew up far on the north end of the city, closer to the Barbary Coast than to “the slot” (the cable car line on Market Street), so this left him exploring an area known for its vice and danger.

It is unclear what Prince’s musical training was exactly, and when it began, but he likely started early, and he had a lot of natural talent on the piano and violin to get him going. At age 16, he was working as a lifeguard out at the piers and forts along the north front of the bay. In 1888, at age 20, he married a woman and moved to another location in this neighborhood out of the major part of the city. In 1892, Prince decided to leave the west coast, picking up everything and leaving for New York, for better music work.

Almost immediately upon arrival in New York, he became integrated into the exclusive and experimental community of Phonograph folks. It is not known who exactly got him into the recording lab first, but when he began making records he was used as a piano accompanist alongside the soon to be famous Frank P. Banta. His first few records were accompanying San Francisco native Dan W. Quinn, alternating with Mr. Banta. He stayed in recording until at least 1895, then as quickly as he started, he stopped recording and left New York. He ended up in the Kansas City area, and in 1898 he married an 18 year old girl named Sadie (according to the circumstances she may not have been 18 when they married). Sometime between 1888 and 1894 he likely divorced his first wife, to make room for this new Sadie girl he met in New York. He and Sadie moved back to New York, and by 1899 Prince was working in his parents’ business of packing fruit.

Back in New York, his old recording friends from a decade before caught wind of his return. At this time the recording folks were all buried in a very progressive publishing venture studio pianist Fred Hylands was running, and former Gilmore’s band cornetist Thomas Clark was leading the Columbia orchestra. Prince saw all that was going on in the recording business, as his connections from the previous decade were still hanging on by a few threads. It took until the end of 1902 for Prince to make his way back into recording labs.

It was a gradual process however, in early 1903, Columbia catalogs still proudly advertised Fred W. Hager’s name as the Columbia orchestra and band director (Hager had taken over Tom Clark’s position in 1901). Prince’s reception with the Columbia crowd was awfully warm, with artists such as Len Spencer taking especial interest in him, writing a few descriptive pieces with Prince. It is likely that Prince burned some bridges with the Edison people (his bridge to Edison being Banta); this is probably why the Edison company stayed away from hiring Prince.

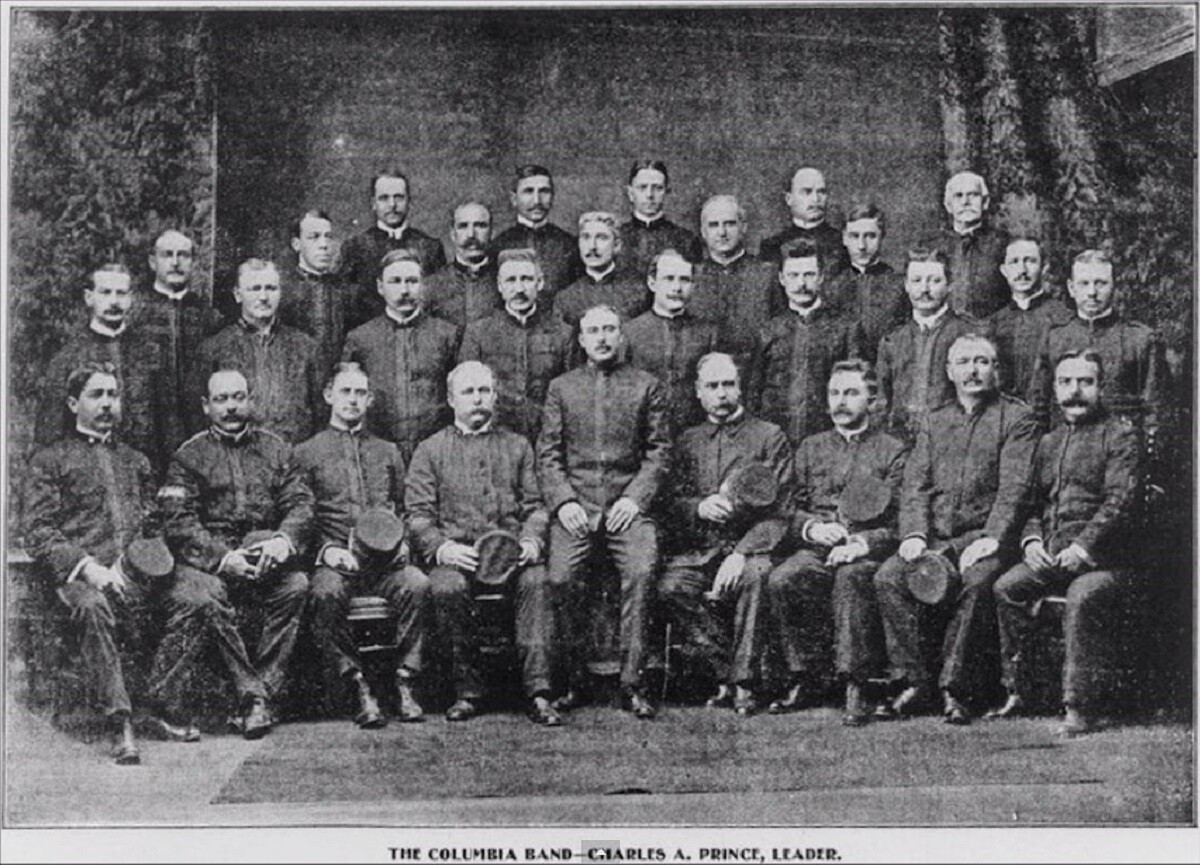

Prince was initially re-hired as a pianist in keeping with his reputation of the previous decade, but this didn’t last. He accompanied a few operatic stars on a now ultra-rare Columbia operatic series. By the middle of 1903 Prince had taken over the Columbia band and orchestra. He had big ideas for this company’s future, and the first thing he wanted to do was purge a large portion of the old orchestra members. Among the musicians to leave under Prince were pianist Fred Hylands, cornetist David P. Dana, clarinetist William Tuson, and several more. Prince utilized Fred Hager’s assistant Justin Ringleben more than anyone else, giving him the job of writing out hundreds of arrangements for his newly christened Prince’s Military Band. He also took the initiative to employ Hager’s awkward younger brother Jimmy as his percussionist, and hire many new musicians he had become acquainted with.

Prince’s band and orchestra proved a hit with record buyers, playing everything from popular Broadway medleys (arranged by Ringleben) to full length operatic overtures. While Prince was employing Jimmy Hager and Ringleben, he enjoyed keeping the two of them as house guests, as they had little desire to stay with Jimmy’s unpredictable brother Fred. Jimmy and Justin weren’t the only famous house guests that Prince so generously but awkwardly housed, another familiar name, who shows up in the 1905 New York census of all places, is Henry Burr (listed as Harry McClaskey). Prince was a kind benefactor for nomads like Burr and Ringleben, but he was known for his difficult and somewhat eccentric personality.

To elaborate on this subject: the status of his married life in the 1910s and ’20s is difficult to track, as he was married and divorced several times between 1910 and 1925, and in most of the census and directories during this period, he wasn’t living with his wife when married. His daughter from his marriage to Sadie remained with him into the 1920s, and in the previous decade the people he was housing varied. The folks he was living with were always strategic to his line of work. For example, in the 1920 census, he was living with his daughter Catherine and her husband Willard who was a playwright, and in 1930, Prince was living with his daughter and his niece who was a chorus girl for the theater he worked for.

While all of the complicated personal stuff was going on, he was working to keep his band up with Arthur Pryor’s band as band and orchestra records were starting to fade out in the 1910s. It was in the 1910s at Columbia that Prince earned his fame, as he was making hundreds of orchestra and band records a year. Prince’s band and orchestra became a household name to record buyers, playing everything from medleys of popular songs to classical pieces by composers such as Camille Saint-Saens. By this time his assistant Justin Ringleben had briefly dropped out of recording, but Prince still employed Jimmy Hager until about 1914.

Around 1918, a New York orchestra director named Robert Hood Bowers was beginning to make his way into Columbia’s recording lab, occasionally directing the Columbia orchestra. Bowers gradually made his way to becoming the music director to replace Prince, and this finally happened in 1923, but it wasn’t time for Prince to leave just yet. Prince returned a few times in 1924 to conduct orchestra records, most likely of arrangements that he had been familiar with in the years before.

During his fading out of Columbia, he worked for the New York Phonograph company who made Paramount records. His time at the Paramount parent company didn’t last. In late 1924, Prince officially left Columbia and signed a brief contract with Victor. While at Victor, Prince conducted a handful of sessions, and returned to playing piano accompaniments. He played piano accompaniment on a few record by Billy Murray and Ed Smalle, as well as a few records by the then fading Peerless Quartet.

By the end of 1925, he was out of recording for good. From recording he went into radio, likely doing orchestra and band conducting or sound effects. It is possible that his old friend Justin Ring got him a steady job on the radio. He was still living in New York in 1930, but by the worst years of the depression he had moved back out to California. While back home in the Bay Area, he worked as a music teacher and conducted small productions in the Marin area. He died at the San Rafael home of his sister on October 11, 1937.

Unlike most of the folks written about in this column, Prince was and still is a very familiar name. In spite of this, what exactly his position and influence in history remains uncertain. Without a doubt, Prince was one of the more colorful characters of the early recording business, living a very difficult life in and out of the studio. He was well known in men’s clubs such as the Masons and the Lamb’s club of New York, and the New York Athletic club, being an avid Baseball man himself. He had little legacy in researcher Jim Walsh’s writings, but Walsh typed a very potent line at the very end of his December 1952 article in Hobbies regarding Prince. The line read, “Conductors may come and conductors may go, but, we may hope, for the pride of Columbia, Prince may go on forever.” This telling quote still carries its weight and humor even 82 years after his death.

Just as a side note, the author visited Mr. Prince’s grave near San Francisco, and his headstone has the signature “note the notes” Columbia logo marked in stone beside his name.

R. S. Baker has appeared at several Ragtime festivals as a pianist and lecturer. Her particular interest lies in the brown wax cylinder era of the recording industry, and in the study of the earliest studio pianists, such as Fred Hylands, Frank P. Banta, and Frederick W. Hager.