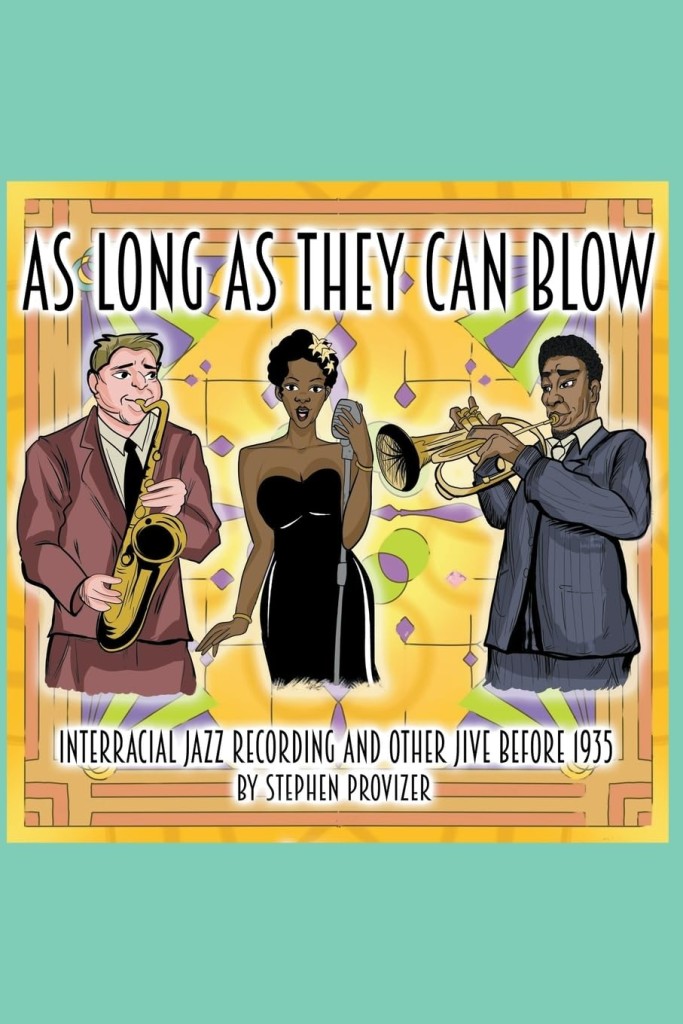

NOTE: This is an edited excerpt of the interview I did with Steve Provizer after reading his new book, As Long As They Can Blow: Interracial Jazz Recordings and Other Jive Before 1935. The full interview, with added music, will air on a forthcoming episode of my weekly radio show, Crazy Words, Crazy Tune: listen at wrfi.org. – RKS

SP: I’m a jazz person; I went to Berklee [College of Music] and I’ve been writing about the music and playing it on the radio for many years. The historian in me knew more than what the popular culture was being told about this music.

Part of it was strictly political and completely understandable: as part of the movement to recognize the presence and the contributions of Black people, that’s what was emphasized. That became the mainstream perspective of the music, and unfortunately, in the process of doing that, there was a lot of bad history. If you’ve seen any of the recent movies, the biographical movies, there’s just so much wrong with them and it bugs me. Like the one about Billie Holiday: so many issues!

RKS: You mean in movies this decade?

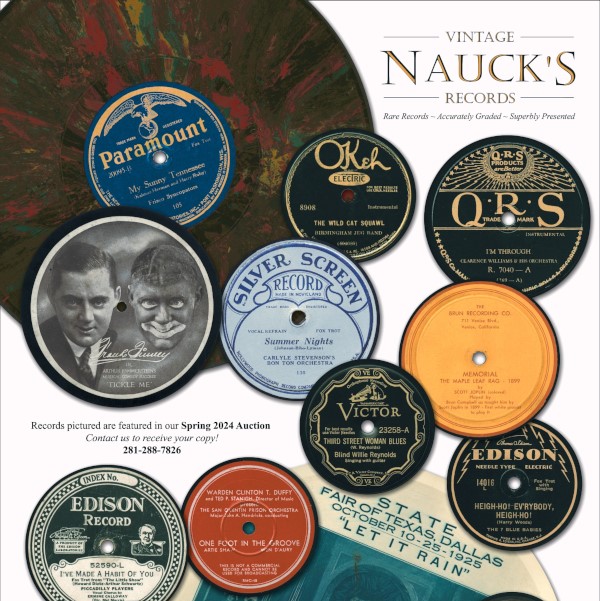

SP: Yeah. And as I began to look into it and actually resolve for myself what was the reality of those situations—you know, what was really happening in the Paramount studio, who were the A&R people, what was the racial component of all that? It was definitely a motivating factor for me to look more carefully into what was happening in the recording studios. Also I think at a certain point a lot of musicians or listeners of jazz, you know, they hear the music of their era and then they begin to go backwards in time. Many do, and I think probably more should.

That certainly was the case with me: I knew my contemporary music, I knew the music from bop and beyond, but I really didn’t know much about swing or the music of the twenties or the teens. And as I was looking into all of this, it drew me in more, the music had more to say to me, I heard more in it. I became more fascinated by the people that we didn’t know. I mean, who do we know from the twenties? So few people. Most people of course know Armstrong and Ellington, maybe Fletcher Henderson, but there were so many people making music.

And they were getting together in an ad hoc, off-the-bandstand way. They were doing sessions together, they were doing rent parties together; they were mixing and intermingling and talking and playing with each other off the bandstand, because they were not allowed to play on the bandstand together. And the recording studio was kind of a logical extension of that kind of interactivity. Nobody was paying a whole lot of attention. You didn’t get the information on the labels, you didn’t know who was black or white, you didn’t really know in a lot of cases who was playing.

RKS: It was sub-rosa, right, and people would take different names—Blind Willie Dunn was Eddie Lang’s name.

SP: Absolutely. So as I got more into it, I was discovering more and more of these sessions, more and more people who deserve to be better known. My God, a biography of Bill Moore? That’s way overdue. If people don’t know, he was a black musician who played trumpet and was on literally hundreds of sessions with white and black musicians.

RKS: I know he was with California Ramblers. You have him with Adrian Rollini and Goofus Five. Certainly a strong, sharp sound he’s got.

SP: He was a good player. And that’s why I call this book As Long as They Can Blow. That’s the attitude that I’m trying to communicate to people, that the music had the capacity to bring people together, because that was the center of their life and their endeavors were all shaped in accordance to that. So it didn’t matter, you know? As long as you could blow.

Of course, there was a lot of bad behavior. There was a lot of racism, a lot of sexism, obviously, and that needs to be told. However, let’s say the pendulum has swung so far over that I’m thinking, let’s move it back a little bit towards a place where people didn’t think strictly in terms of identification on the basis of their race. That was not the ultimate determinant. For some people it was, but for many people it wasn’t. So let’s look at that.

And that’s why messages that tag people, that flatten them out, and de-dimensionalize the characters, they kind of drive me crazy. Let’s try to look at the whole person here, as much as we can.

RKS: It’s very pleasing to hear that it was for you a search for further nuance that drove you to look more deeply. Because I think it’s such a big problem for the human species, for this country particularly. Black and its opposite creates a polarizing worldview. I’ve stopped even using the w-word: I prefer “person of pallor,” although I think that one’s still ahead of its time.

I’m interested in how the progress of Black music and musicians in show business across the board either parallels or differs from the development of civil rights, which maybe centers in large part on the struggle to end segregation but is also, underneath, about, you know, will we accept the idea that African Americans are human beings, and that they’re Americans, and an important and legitimate part of the American national character? Can we handle an African element in US popular culture?

SP: Well, one thing I talk about briefly in the book is that in the twenties, America thought of several other groups as not being white, including Jews and Italians. And there was an other-ness; it was another aspect of why these people came together. Why not? You’re going to identify more with somebody else who’s alienated from the main culture. And music was one part of it, and your nationality and color were other elements.

SP: Well, one thing I talk about briefly in the book is that in the twenties, America thought of several other groups as not being white, including Jews and Italians. And there was an other-ness; it was another aspect of why these people came together. Why not? You’re going to identify more with somebody else who’s alienated from the main culture. And music was one part of it, and your nationality and color were other elements.

I mean, when people criticized jazz, a lot of it was anti-semitic and anti-immigrant. The whole thing was like a cabal to them, that was going to take down this Puritan nation of ours. And the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover got right in there with it.

RKS: And Harry Anslinger of the FBN (Federal Bureau of Narcotics), who tied the cannabis herb, which was legal, to these non-pink populations and to the music. So there’s this conservative campaign of moral panic.

SP: And the recording industry paid close attention to this. They tried to hedge their bets in certain ways. They were about making money, but they recognized that if they were going to be in people’s living rooms, they had to project a certain image of a clean, all-American thing.

RKS: Yeah, Edison was one of those people. He didn’t even want his new machine to be part of the entertainment industry; he wanted it to be a business machine. But in the case of Bert Williams and George Walker, the Victor Talking Machine Company in 1901 hired them and advertised that they were going to be the highest-paid performers in this new industry.

SP: Boy, how to parse that is so difficult. You look at Polk Miller. He was literally a Confederate officer. He recorded and he traveled with a black male vocal group. Somebody try to make sense of that. It was part of that it-wasn’t-so-bad-for-the-dark-people sort of thing. It was Old Folks at Home, it was Swanee River, that was the vibe. It was Lost Cause and nostalgic.

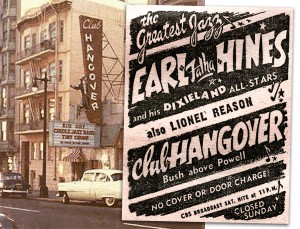

RKS: There’s a strong element of that in the “Dixieland” repertoire. Why do they even call it Dixieland music, right?

SP: That was the word that was adopted by black musicians themselves, later on, after the fact.

RKS: There are all these nuances, right? The cakewalk is a black parody of the dances they were seeing their masters and their masters’ classes do.

SP: That’s right. But I think it’s fair to say, statistics do bear up the fact that it was just a whole lot harder for black musicians to get recorded than white musicians. That was the way it was. And then, of course, another layer of irony is that white singers, especially white female singers, ragtime singers—Sophie Tucker—their bona fides came from sounding black. Saying they were delivering the genuine Negro music.

You know, it was kind of a yin-yang thing, because on the other hand, you had parlor music, and the legacy recording companies always tried to continue these strains. You know, the Victor Red Seal, the classical recordings, Caruso and all of that. At the same time, they were trying to deliver this more funky experience, which was initially ragtime, then that went through transitional phases. Wilbur Sweatman’s music, I think of it as transitional; it’s largely ragtime to me, and yet it has some of the qualities of jazz. James Reese Europe had a lot of jazz qualities, although it is essentially ragtime, but there’s this crack in the door there that lets some jazz in.

RKS: Well, ragtime hit between 1895 and 1900; that’s when Joplin wrote “Maple Leaf Rag.” So then we’re talking more than a dozen years later with this period. The culture’s already moved past it. Irving Berlin recognized that because he appropriated the term in “Alexander’s Ragtime Band.”

But what Europe did, paired with Vernon and Irene Castle in live venues, teaching dance at this time when there was really a live social issue: how can male and female persons engage in a social dance to this music that’s this damn hot? That’s a real problem! The animal dances, different awkward European ways of comprehending what is taking place, you know, below the waist. Rationalizing and civilizing that into one animal dance, the foxtrot, seems like what the Castles and Europe did together, and they deserved the Nobel Peace Prize!

SP: And when you think about it from the metaphorical perspective that Europe is black and they were white: here we have the two strains that I was talking about, the high and the low, trying to merge, trying to find some kind of synergy. Which they did! Those dances, America became a dancing country. It was a formula that worked.

RKS: A pleasurable solution to a social problem. Let’s skip ahead a few years to maybe ’27-28, which gets us to Eddie Condon. He’s one of the people whose voices you’ve knocked into a dramatic monologue, so what inspired you and made you start doing that?

SP: Well, one of the reasons is because his voice is so clear in what he wrote in his autobiographies. We Called It Music is the main one, and from what everybody says, that’s the voice he conveys, sort of a wiseass, all-knowing guy. Slick was his nickname. So having that, which is a rare commodity in the early days, a written testimony of that kind is so rare. And he was very instrumental in some key sessions. So I thought, let’s use what he gave us and try to shape it into something that was a story—beginning, middle, and end. So that’s why I chose Condon and basically why I chose Mezzrow, because he also has one of the great autobiographies in jazz, Really the Blues.

SP: Well, one of the reasons is because his voice is so clear in what he wrote in his autobiographies. We Called It Music is the main one, and from what everybody says, that’s the voice he conveys, sort of a wiseass, all-knowing guy. Slick was his nickname. So having that, which is a rare commodity in the early days, a written testimony of that kind is so rare. And he was very instrumental in some key sessions. So I thought, let’s use what he gave us and try to shape it into something that was a story—beginning, middle, and end. So that’s why I chose Condon and basically why I chose Mezzrow, because he also has one of the great autobiographies in jazz, Really the Blues.

RKS: In your Condon monologue you mention the show Hot Chocolates, for which Fats Waller wrote the score, and it was the show in early ’29 where Louis Armstrong, who had just moved back to New York, had his breakthrough. He started in the pit band, playing “Ain’t Misbehavin’,” but he’s such a hit they bring him up and he sings it, and it seems like this begins the rise of Armstrong not just as a star trumpeter but a star entertainer. He seems like a key guy in this, and in recordings he’s paired with Mezzrow and with Jack Teagarden, then with Hoagy Carmichael and even Jimmie Rodgers.

SP: It was pretty much an inspiration to get Teagarden together with Armstrong. They hadn’t apparently met. Of course, Teagarden came to town and he was the new guy. Stylistically, he brought something really new, a deep blues feeling, and of course his voice and his trombone playing were so well matched in terms of delivering an emotional message to an audience.

SP: It was pretty much an inspiration to get Teagarden together with Armstrong. They hadn’t apparently met. Of course, Teagarden came to town and he was the new guy. Stylistically, he brought something really new, a deep blues feeling, and of course his voice and his trombone playing were so well matched in terms of delivering an emotional message to an audience.

RKS: But of course, Satchmo knew the pale musicians and their scene. He certainly interacted with Bix Beiderbecke. He would have known Teagarden’s music even if they hadn’t met.

SP: People were sitting in with each other all over the place. I don’t know what Bix said, but I do know that Armstrong referenced Bix a lot, called him my man. Bix sat in with him for sure. You know, Armstrong had an operatic inclination. He listened to opera, big opera fan, and Beiderbecke was on one end of that. Call it bel canto: it was creating mellifluous lines, and I’m sure Armstrong heard and loved that.

RKS: Probably it plays into what I was trying to get at with Armstrong’s taking on a new dimension as a pop star. It wasn’t just about him. It was about a cultural integration happening in the music, where you get a jazzy style of popular song. Because early on, jazz was this hot, syncopated instrumental music during the rag-a-jazz period, and the song being sung by black singers was blues—this sort of northern blues, the first blues that got recorded. Mamie Smith and the people up north who’d been on vaudeville stages were singing this kind of bluesy song. It wasn’t much like popular song, although it had Tin Pan Alley elements.

But by later in the twenties, you have first Armstrong, then other black singers taking the Broadway music that had gotten syncopated, thanks to Gershwin and Irving Berlin and Sissle and Blake with Shuffle Along. So that whole thing is an integration of the European and African musical traditions.

SP: The “pop” music songs of the day had heretofore been rendered in almost a direct line from parlor music in the late nineteenth century.

RKS: Yeah, more Victorian. But that whole southern Lost Cause thing became less and less relevant. It became more and more possible for people of different hues to make beautiful music together like these guys are doing.

But also, I think there really is a racial and cultural synthesis in how improvisation came into the style of pop song-making. These songwriting cats from Broadway by the late twenties-thirties really had it. Their songs were usable in that way. Even Rodgers and Hart, even Jerome Kern, the somewhat more highbrow among that gang. Cole Porter. Part of what, we could argue, is and has been great about America is that coming together. What’s the word, a sublimation, in the Freudian sense, a racial sublimation is taking place in that music.

SP: Wow. Well, I will say this: jazz buoyed those songs and brought out a kind of timeless quality to them that their original rendition might not have provided to them over the course of time, because they were often sung by soprano soubrettes and baritones, people who had very limited rhythmic skill.

RKS: Right, and because they weren’t letting black vocalists sing these romantic songs. People were stuck up about that sort of thing. Sissle and Blake ran into that, certainly Williams and Walker in the ’aughts.

SP: But don’t forget that a lot of those ballads that were being performed were not being recorded because the recording companies didn’t want them recorded by black bands.

RKS: They didn’t want it either!

SP: They wanted the hot material. So our recording record is not well indicative of what people were actually performing.

The full interview, with added music, will air on a forthcoming episode of my weekly radio show, Crazy Words, Crazy Tune: listen at wrfi.org.

Steve Provizer is a brass player, arranger and writer. He has written about jazz for a number of print and online publications, and is most recently the author of As Long as They Can Blow: Interracial Jazz Recording and Other Jive Before 1935, now available through amazon.com. Write him at [email protected].