Introduction

Milton “Mezz” Mezzrow was a jazz musician/marijuana seller and author (with writer Bernard Wolfe) of a singular autobiography, Really The Blues. The book, set largely in the 1920s-’30s, is one of the few autobiographies written by an early jazz musician and is arguably the most entertaining and informative.

That said, writing about Mezzrow in 2023 is a bit of a minefield. For one thing, the depiction of Mezzrow’s life and times as told in his own, highly subjective voice is so vivid that it’s easy to be carried away and pay little heed to the historical gaps or inaccuracies in the book. Secondly, Mezzrow was a white Jewish man who identified completely with African-American culture. He lived in black communities and married a black woman. When he was sent to prison, he told the guards he was “negro”—also the race on his draft card. Much of Really the Blues is taken up with differentiating black from white culture—always to the detriment of the latter. Today, many people see such a position as privileged posturing.

If you read the book, you can draw your own conclusions about Mezzrow as an object of cultural scrutiny, but his actions—not just his words—show that he was sincerely in thrall to jazz and black musicians. And, while there are varying opinions about his playing, he was, at his worst, competent and at his best, convincing. Certainly, he was no dilettante when it came to “living the life.”

Something else is inarguable—that Mezzrow played an important role in fostering interracial activity in jazz. As such, his story makes a logical successor to the one I told in the voice of Eddie Condon, who was a pioneer in organizing recordings with interracial groups—some of which Mezzrow participated in. Mezzrow also organized several interracial recording sessions and moreover, put together what was arguably the first public-performance group comprised of black and white jazz musicians—The Disciples of Swing. In Really the Blues, Mezzrow seems unsure about the facts surrounding the denouement of the story and unfortunately, accounts in the media are few and contradictory. So, for the moment, we will let Mezzrow tell the story, primarily in his own words…

I

It’s the summer of 1933. Harlem. I’m manicuring some ribs at the Barbecue when a stocky white man wearing a plaid jacket two shades louder than a checkboard yells “Mezz!” and grabs my hand. “Drop around to my office and I’ll show you something that’ll make your eyes pop out.” I thought grift, but I lamped the engraved card he handed me. He was Gerald X, one of the biggest radio booking agents in the country. My heart jumped.

I showed up a few days later, waded through a corps of secretaries into his office and watched while he dragged out a microscope.

“I collected about a dozen species of marijuana…” He proceeded under the microscope to show me the differences between them and capped it off with a sample of the Mezz—my own brand of muta. It sparkled brightly with all the colors of the rainbow. He was gonna show me how to get rich.

“All we do is, we get some smart attorney, form a corporation and push the stuff on a national scale.”

“Gerald, I came up here to beg you to sponsor me with a mixed band and here you want me to get deeper into something I’m trying to break away from. It’s a no-go. If you want to go into a new business, let me tell you, I know some of the greatest musicians and they’re out of work. I could get them for a band just by lifting the phone.”

“I don’t know, Mezz.”

“Just think Gerald, the first mixed band in history, the top colored and white boys playing together.”

“Give me a couple of days to think it over. I’ll give you a ring.”

Two days later, August 18, I was in his office, trying to steady my hand so I could sign a contract that mentioned net earnings over $40,000 a year and some other fantastic jive I couldn’t even read. The scheme was to whip my band into shape, then get a big network to OK us for sustaining.

Unfortunately, the radio people didn’t go for the mixed-band idea. But at least they agreed to let me have Alex Hill, a fine colored arranger, to front the band, and also said I could use a great colored act, the Five Spirits of Rhythm. It was an opening wedge, anyhow.

The boys I wanted to use were all over the country, but I rounded them up and they agreed to come just for carfare. Coin was scarce, so Pee Wee Russell, Bud Freeman, and Floyd O’Brien all had to stay with me and my wife and kid at our place in the Bronx. I cornered Fats Waller at Irving Berlin’s [publishing house] and he sat down and wrote me two arrangements on the spot—Walkin’ the Floor and John Henry. Alex Hill was all for me. I explained to him how I was fighting for a mixed band, but that the man said to wait until I got some power. Why wait, I wanted to know. That’s been going down for years, everybody waiting and nothing happening.

“Mezz, I think the man is right,” Alex said, “whether we like it or not. You got to crawl ’fore you can walk, so take it easy Jim and we’ll see what we can do. Just make sure you get enough money to keep me in gin and I’ll knock out some of the finest arrangements that ever was put down on paper.” Alex came up with 15 arrangements, and he and I sat up all night at my piano, working out about one arrangement a day.

We went into rehearsal and the band sounded beautiful. Good old businessman Red McKenzie showed up and went wild about the Five Spirits of Rhythm. He went over and sold the act to the Famous Door on 52nd St. and they were the first colored group on 52nd St. I didn’t mind losing them. I was glad to see them work steady. I was walking on clouds and it wasn’t just the hop that sent me.

Then came our audition. Alex Hill directed and when it was over, he said: ”Mezz, I think I can truthfully say I was the first negro to direct a white band in these studios.”

We went over big and were okayed for a sustaining program and got a letter of credit so we could buy uniforms. We even already had a gig, replacing Guy Lombardo in a Long Island café. Some of my dreams were beginning to come true at last.

Then, one day after rehearsal, I noticed all the boys were packing up in a big hurry and I sensed something in the air. Alex hipped me to the fact that Red McKenzie had arranged a rehearsal with a politician’s son named Cass Hagan who wanted to be a bandleader. They’d asked Alex to do the arrangements, but he put them off and they got Benny Carter. I was ready to quit right then, but Alex convinced me to let it play out.

Turned out Benny made the arrangements so difficult they couldn’t get through them.

“Benny sure is friend of yours,” Alex told me. “He must have written them that way on purpose.” That’s the way with the race. Your friends give you a boost and grip up the ones who aren’t in your corner, and not a peep do you get out of them about it. Their actions tell the story.

But then I learned that Condon had arranged for that band to record for Brunswick. Alex asked would I be angry if he did the arrangements—they were paying good money and he needed some then. I told him OK. I knew he was solid for me and it wasn’t his fault. Then I decided to throw in the sponge. Chalk up another victory for the entrepreneurs.

II

Not long after, I got a little of my own back when I told my tale of woe to Jack Kapp, recording manager at Brunswick.

“If I give you a date,” Kapp said,” your records won’t sound like Condon’s, will they?” I told him no way and we got the date. Alex, me and Benny Carter did the arrangements and I pulled a crew together that included Ben Gusick, Max Kaminsky, and Freddie Goodman on trumpet, Floyd O’Brien on trombone, Jack Sunshine, guitar, Pops Foster on bass, Jack Maisel, drums, me on alto and clarinet and Teddy Wilson on piano. For one afternoon, at least, I had a real mixed band.

A year later, thanks to Hughes Panassie, RCA-Victor contacted me for another mixed session. On this date we had no fewer than four colored orchestra leaders who were on their way to the top: Benny Carter on alto sax, Chick Webb on drums, John Kirby on bass, and Willie the Lion on piano. So once again, I was a mixed-band king for a day.

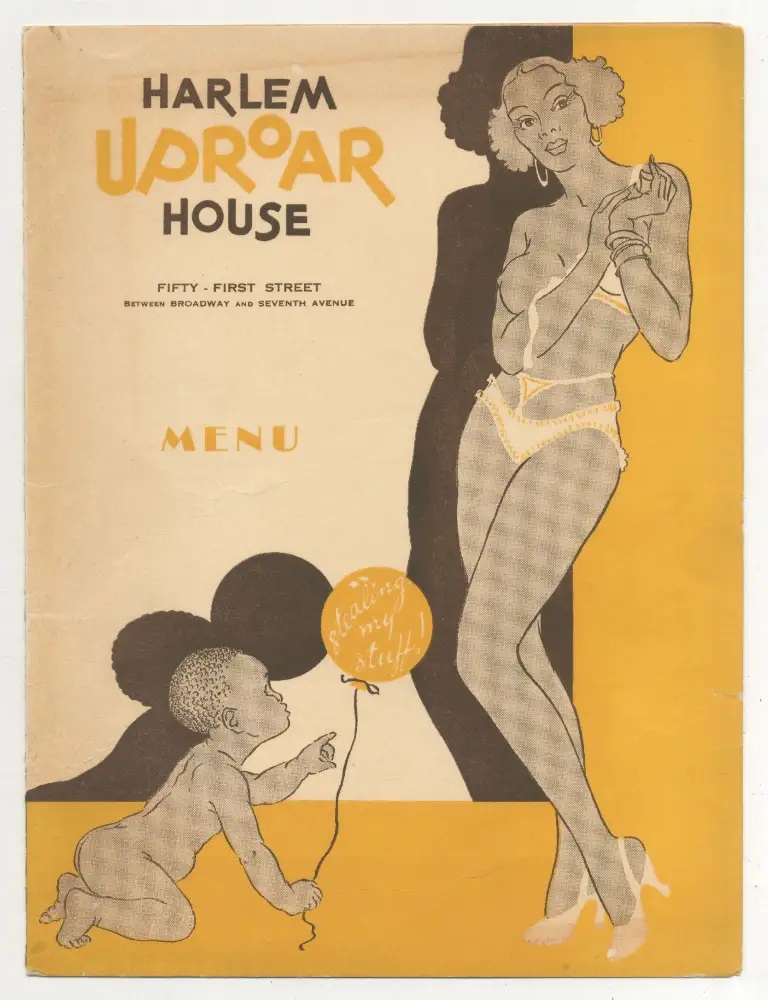

I had a couple more mixed sessions in 1936 and early 1937, then, later in ’37 I suddenly woke up to find myself leading an all-star mixed band right on Broadway. The color line along the Great White Way wasn’t exactly broken, but it sure got dented some. I had done a couple of sessions for O.B. (Eli Oberstein) at RCA-Victor. I told him that he was the only one who understood what it was all about and asked if he could get me some backing for a mixed band. A few hours later, we were huddled over a steak at the Harlem Uproar House, a joint on 52nd St. just off Broadway with the owner of the joint, Jay Faggin.

“Here’s the idea, Jay.” O.B. says. “Mezz organizes a 15-piece all-star mixed band. We open it here at the Uproar House on November 20, the same night we inaugurate the RCA-Magic Key program on the air, so we spot the band on our radio show for a buildup. Recordings to follow. Promotion. My attorney will draw up corporation papers and we’ll all be in business. “

“Set,” said Jay Faggin.

“!” I said in a low whisper. I choked on my drink.

We decided, instead of just killing time with the usual line of chorus girls, we’d get five teams of Lindyhoppers from the Savoy Ballroom; we’d spot Hazel Scott in the floorshow. Willie the Lion Smith for piano specialties; Lovey Lane would do dance specialties; Flash Riley would be teamed with her in a spectacular African dance routine. Dolly Armendra, a sensational female trumpeter would be featured with the band and the Casares Brothers Trio would play between our sets. It was really shaping up.

Now to get us a hunk of personnel. Fats Waller was doing a single, so we got his clarinet and sax player Eugene Cedric. Frank Newton gave John Kirby his notice and joined on trumpet. Sidney De Paris did the same with Charlie Johnson’s band and was our second trumpet. George Lugg and Vernon Brown came aboard on trombone. I sent Max Kaminsky train fare and he came from Boston to be our third trumpet. Then I hired Bernard Addison on guitar, Elmer James on bass and tuba, John Nicollini on piano, with Zutty Singleton and drums and me. That made fourteen-seven white, seven colored, and Dolly Armendra made fifteen.

OK, everything was greased for us. O.B. came through with some gold so Zutty could get new drums and pay his back rent. Arrangers worked for us on the cuff. Manny’s supply house furnished all the mutes, mute racks, metal hats and drum sticks and wasn’t in any hurry about the dough. Cy Devore togged us all in tuxedos.

III

Opening night, the Harlem Uproar House at 209 West 51st St really came down—it looked like maybe a new day was dawning, at least in one small branch of the entertainment world. What publicity we got. “Mixed Band Bows on Broadway,” a full-page headline in Billboard proclaimed. “Mezzrow Takes Ofay and Sepia Swingsters Out in the Open…Not just a trio or a quartet for the refreshing swing interludes as one gets it from [Benny} Goodman at the Hotel Pennsylvania. But a white leader fronting a bandstand that will show 15 musical swing stars culled from the Caucasian and Negroid races…Mezzrow aptly named his new combo the “Disciples of Swing.”

A couple of wonderful weeks trillied by; the house jammed every night, rave notices, everyone in the show putting all his heart into it. Then one morning, a messenger sent by Jay Faggin came to my house: “You’d better come down to the Uproar House. Something terrible has happened.” That’s all it said.

It was worse than anything I could have dreamed up; cops and reporters, everyone looking tense and upset. The first thing I noticed was that a large, framed display posted quoting Billboard’s writeup had been smeared with a hell of a big swastika in bright blue paint. I ran downstairs. There was a gang of people standing on the dance floor, looking at a great big swastika painted right across on it. All the chairs and tables were overturned. The place was a mess. Looked like somebody sure took offense at the idea of a mixed band.

But that night the place was packed and we put on a wonderful show. It was like that the following nights too. Until the night when we came to work and found the marquee lights out and a sheriff at the padlocked door, and a poster tacked up informing whom it may concern that the creditors had gotten a court order and closed the place up. It seemed that the creditors had been wanting to appoint another trustee and ease Faggin out, but he’d put up a fight and this was the result.

Right away, some people who wanted it that way began to say I-told-you-so, it just proves the American public won’t stand for a mixed band, etc. Well, for the sake of the record, let me say that band was one of the biggest successes Broadway has ever seen, and the creditors were so amazed at the business we were drawing that they were all set to invest plenty of thousands more in the joint, and I know because I’d had a meeting with them and they told me so. It was that legal squabble between Faggin and these other guys that closed the place down… And maybe those swastikas made the creditors a little jittery too; I don’t know.

Right after they closed the place down, the Disciples of Swing got booked into the Savoy Ballroom, but in the meantime, Artie Shaw, Benny Goodman and Tommy Dorsey were dickering for some of the white guys in the band, and I began to lose my men to them, so we had to cancel that engagement.

It wasn’t the fault of the musicians—that’s for sure. Musicians like to go where they can play music. They follow their noses to where there’s a job, where some eating money is to be had and all the paper contracts and deals in the world won’t stop them. If I got a band together, plenty of my old pals would join it because they loved to play our brand of music. But when hard times fell on us, they had to scuffle in another alley. It was the same old bout with economics, and I’d wind up on the losing end every time. And so, the Disciples scattered to the four Jim-Crow winds again.

♫

Personnel of The Disciples of Swing: Eugene Cedric, t.s., cl., Mezz Mezzrow, cl, a.s., Frank Newton, tpt, Sydney De Paris, tpt., Max Kaminsky, tpt., Dolly Armendra (Jones, Hutchinson), tpt (feature), George Lugg, tb, Vernon Brown, tb., Bernard Addison, gtr., Elmer James, sb, tuba, John NIcolini, p., Zutty Singleton, dr.

Steve Provizer is a brass player, arranger and writer. He has written about jazz for a number of print and online publications and has blogged for a number of years at: brilliantcornersabostonjazzblog.blogspot.com. He is also a proud member of the Screen Actors Guild.