1924 found America deep in the Jazz Age with speakeasies, bootleggers, and hot jazz as the soundtrack. Calvin Coolidge was president (winning re-election in November), the business of America was business, and times were good for many Americans, at least those who did not have the misfortune of being poor.

Seven years after the historic recordings of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band and four after Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues” launched an unexpected blues craze, the record business was booming. 1923 had brought the recording debuts of Jelly Roll Morton, King Oliver, Louis Armstrong, Johnny Dodds, Sidney Bechet, and Bessie Smith as record labels, realizing that there was a strong market in the black populace, eagerly recorded African-American jazz artists.

1924, 100 years ago, was not quite as groundbreaking as the previous year but there were many significant events that took place in recording studios. While recordings were still being made acoustically and drummers were not able to utilize their full set, the general recording quality had steadily improved during the past decade. Jazz itself was starting to change its emphasis from freewheeling ensembles to arrangements and soloists.

Here are ten of 1924’s major jazz recording events, in roughly chronological order.

Feb. 18 – Cornetist Bix Beiderbecke joined the Wolverines in Dec. 1923. The group, a spirited young octet, was quickly emerging in the Midwest as one of jazz’s top bands. Only 20 at the time, Beiderbecke already had a distinctive cool-toned sound and a harmonically advanced style, sounding unlike anyone else at the time. On Feb. 18 with the Wolverines he made his first recordings, “Fidgety Feet” and “Jazz Me Blues.” While the Wolverines were initially ensemble-oriented, as the year progressed Bix would become the group’s dominant soloist, particularly on Oct. 8’s “Big Boy” where he was featured on both cornet and piano. Beiderbecke would make a major mistake that month by deciding to leave the Wolverines for a position with the Jean Goldkette Orchestra; Jimmy McPartland became his replacement before the group broke up. When it was discovered that Bix could not read music, he was fired by Goldkette although promised a spot in the future when he learned to follow arrangements. In 1926 he would return.

Feb. 23 – One of the most unlikely commercial successes of 1924 was the Mound City Blue Blowers. Red McKenzie played the comb, sounding a bit like a kazoo by putting paper over it and then blowing and humming. He led a unique trio with Dick Slevin who played a more conventional kazoo, and banjoist Jack Bland. Their recording of “Arkansas Blues” and “Blue Blues” on Feb. 23 was a big seller. The group, which by late 1924 also included guitarist Eddie Lang, flourished for a year.

Mar. 14-17 – The Okeh label went on a historic field trip in March 1924, recording some jazz artists who were based in New Orleans and had not been documented. On Mar. 14 they recorded two numbers by singer Lela Bolden (who was accompanied by New Orleans bandleader/violinist Armand J. Piron and pianist Steve Lewis). This was followed by sessions featuring trumpeter Johnny De Droit’s New Orleans Jazz Orchestra (a septet), cornetist Johnny Bayersdorffer’s Jazzola Novelty Orchestra, singer Ruth Green, the Crescent City Jazzers (a septet/octet that included trumpeter Sterling Bose) and Fate Marable’s Society Orchestra.

Starting in 1907, pianist Marable led a series of legendary New Orleans jazz bands that performed on steamboats traveling up and down the Mississippi River. Among his sidemen at various times were Louis Armstrong, Red Allen, Johnny Dodds, Baby Dodds, Zutty Singleton, and even Erroll Garner and Jimmy Blanton. Marable only had one chance to be in a recording studio and the results from Mar. 16 (“Frankie and Johnny” and “Pianoflage”) were considered disappointments due to the poor recording quality. But, as a cleaned up reissue put out by Off The Record label in recent times shows, the music was better than expected.

While it is a tragedy that such New Orleans lost legends as trumpeters/cornetists Emmett Hardy, Chris Kelly, Chris Petit, and Manuel Perez were not documented by Okeh (or anyone else), the label did preserve rewarding music that shows that the New Orleans jazz scene in 1924 was still very much alive.

June 9 – Jelly Roll Morton, one of the most important pioneers in jazz history as a pianist, composer, arranger, bandleader and occasional singer, had made his first recordings in 1923. Those included superb piano solos, a few primitive band sides, and guest appearances with the New Orleans Rhythm Kings on two of the first integrated jazz sessions. In 1924 he continued in a similar vein. While his three group sessions are disappointing (Morton would have to wait until 1926 before recording classics with his Red Hot Peppers), his four piano solos for Paramount during April and May, and particularly his nine solo sides for Gennett on June 9 are memorable. Of the latter, Morton sets the stage on “Shreveport Stomps” and “Jelly Roll Blues” for later group recordings, outlining all of the parts on piano. Other highlights include “Perfect Rag,” “Tia Juana,” and “Stratford Hunch.”

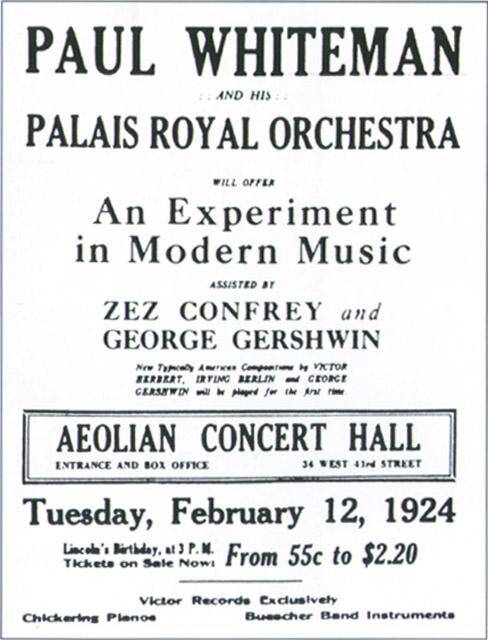

June 10 – Paul Whiteman, whose title should have been “King Of The Jazz Age” rather than the obviously inaccurate “King Of Jazz,” led the most popular big band of the 1920s and was a household name by 1924. The previous December, Whiteman had asked George Gershwin if he could write an extended composition for his orchestra that he could perform at an ambitious Aeolian Hall concert taking place on Lincoln’s birthday. Gershwin turned down the offer because he felt that he did not have enough time, so the composer was rather surprised on Jan. 3 when he read in the New York Tribune that he had begun work on a jazz concerto for the upcoming concert! Whiteman soon persuaded him to write the piece despite there only being five weeks left.

A month later, the first draft of “Rhapsody In Blue” was completed. At Whiteman’s “An Experiment In Modern Music” concert of Feb. 12, as the second-to-last piece during a lengthy program, “Rhapsody In Blue” became an immediate sensation. While not technically jazz, it succeeded at Gershwin’s goal of musically depicting aspects of American life during the jazz age. The composer on piano improvised a few sections during the concert. The debut recording on June 10 is quite unique.

In addition to Gershwin’s spontaneous soloing, it includes a few chuckles from the clarinet, some slap-tonguing by the saxophones, and roles for the bass clarinet, tuba and banjo. While cut back a little in length so it could fit on two sides of a 78, the jazz elements, primitive recording quality, and general charm make this performance a delight. By the time that Whiteman recorded a second version of “Rhapsody In Blue” in 1927 (with Gershwin back on piano), the improvising and effects were gone. It would be up to jazz musicians (rather than classical orchestras) to come up with creative versions of this piece, but the 1924 recording stands alone.

July 30 – Although Paul Whiteman was much better known to the general public, the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra was the leading big band in jazz. However, despite Don Redman’s often-futuristic arrangements, the band’s top-notch musicianship, and the presence of Coleman Hawkins on tenor, the group really did not swing in its earliest period. Its phrasing was often staccato-oriented, solos were sometimes filled with dated effects, and much of the material was more suitable for dancing than for listening. But then, after quite a few recordings, during the second half of their version of “Charley, My Boy,” the band swings on records for the first time. The addition of trombonist Charlie Green earlier in July was a big help, but one wonders where the inspiration came from. Louis Armstrong would not be joining the band for another two months and the swinging and riff-filled ensembles on “Charley, My Boy” were not heard on the ten selections that Henderson recorded in the interim.

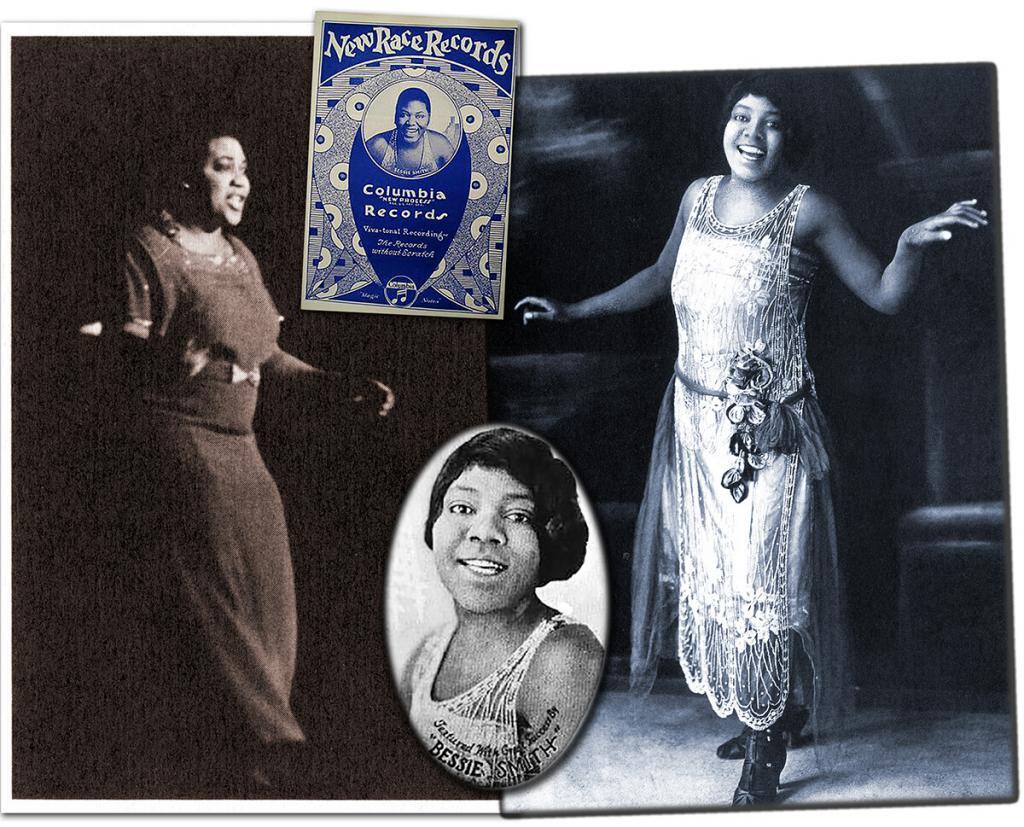

Sept. 28 – The blues craze, which had begun in late 1920, was slowing down although, particularly during the first half of 1924, many blues-oriented singers were still being rushed to the studios in hopes of getting another hit on the level of “Crazy Blues.” Along the way there were recordings by dozens of African-American female singers. Some would become famous while many ended up becoming obscure. Just to name 35, in 1924 there were Ida G. Brown, Dora Carr, Ida Cox, Ethel Finnie, Helen Gross, Lucille Hegamin, Edmonia Henderson, Rosa Henderson, Edna Hicks, Mattie Hite, Alberta Hunter, Edna Johnson, Margaret Johnson, Maggie Jones, Thelma La Vizzo (who that year introduced “Trouble In Mind”), Virginia Liston, Sara Martin, Viola McCoy, Hazel Meyers, Josie Miles, Sodarisa Miller, Monette Moore, Dolly Perkins, Ma Rainey, Irene Scruggs, Clara Smith, Laura Smith, Trixie Smith, Priscilla Stewart, Annie Summerford, Eva Taylor, Sippie Wallace, Ethel Waters, Lena Wilson, and Edith Wilson.

Towering above them all was Bessie Smith, the Empress of the Blues. She had recorded 28 songs the previous year and followed it up with 26 more in 1924. While none of the latter selections would become all that famous, a good example of her powerful singing can be heard on her Sept. 28 recordings of “Weeping Willow Blues” and “The Bye Bye Blues.” That session, which also includes pianist Fletcher Henderson, has the Empress joined by trombonist Charlie Green (whose playing she loved) and is the first one with her favorite cornetist, the unrelated Joe Smith.

November – For a few months in 1923, Duke Ellington had been in New York with a few of his musician friends, but it was a struggle to find work and survive so he returned to his native Washington D.C. Things were different when he came back to the Big Apple in 1924 as the pianist with Elmer Snowden’s Washingtonians. A dispute over money soon resulted in Ellington becoming the group’s leader and the beginning of a half-century of stirring music. In November he made his first known recordings including a few titles with singers Florence Bristol, Alberta Hunter, and Jo Trent, and one song with drummer Sonny Greer (as Sonny and the Deacons).

Most significantly Ellington and the Washingtonians (a sextet with trumpeter Bubber Miley, trombonist Charlie Irvis, and altoist Otto Hardwicke) waxed “Choo Choo” and “Rainy Nights.” The Ellington sound was already present on those titles although it would take another two years before Duke was able to get it back again with Miley (who during 1924-26 was often employed elsewhere) and trombonist Tricky Sam Nanton as major contributors to Ellington’s “jungle band.”

December – Joe “King” Oliver had led the top jazz group of 1923, his Creole Jazz Band with Louis Armstrong and Johnny Dodds. However in 1924 they broke up over money and Armstrong’s desire (with his wife Lil’s urging) to no longer play second cornet. Oliver continued working in Chicago but, other than two songs backing the vaudeville team of Butterbeans and Susie, he was off records the entire year, with one exception. At a December session, the cornetist made his only recordings with Jelly Roll Morton. Their duet renditions of “King Porter Stomp” and “Tom Cat Blues” are charming and swinging.

October-December – It would be a slight exaggeration to say that when Louis Armstrong joined Fletcher Henderson’s orchestra, he introduced swing to New York. After all, Phil Napoleon had been playing swinging trumpet in NY as early as 1921. But it would not be an overstatement to say that Armstrong permanently changed the way that many New York-based musicians played. While the Henderson big band was highly rated, many of its star sidemen seemed to think that “playing hot” meant coming up with repetitive staccato phrases that filled up the space.

Armstrong, who was initially perceived by some of the members of Henderson’s band as a primitive from New Orleans who wore out-of-date clothes, silenced those critics as soon as he picked up his cornet. His ability to tell stories in his solos, use of space for dramatic effect, beautiful tone, and fearless solos were impossible to dismiss. Very soon not only the other Henderson soloists but also arranger Don Redman was emulating his ideas and approach.

During the last three months of 1924, Armstrong was not only taking short solos on Henderson recordings (including “Shanghai Shuffle,” “Copenhagen,” and “Everybody Loves My Baby” with the alternate take of the latter having his first if brief vocal), but he was a guest soloist on sessions that resulted in Ma Rainey’s “See See Rider” (Oct. 16), Virginia Liston’s “You’ve Got The Right Key But The Wrong Keyhole (Oct. 17), Alberta Hunter’s “Nobody Knows The Way I Feel This Morning (Dec. 22), and teaming up with Sidney Bechet in Clarence Williams’ Blue Five including “Texas Moaner Blues” (Oct. 17) and Bechet’s sarrusophone feature on “Mandy, Make Up Your Mind” (Dec. 17). It was still the early phase of Louis Armstrong’s career but he was already pointing the way towards the future.

St. Cyr Front: Fred Garland, Freddie Keppard, Elwood Graham, Kenneth Anderson,

Jerome Don Pasqual, Jimmie Noone, Joe Poston, Clifford King.

Some of the other jazz recording sessions from 1924 deserve an honorable mention. These include Piron’s New Orleans Orchestra’s “West Indies Blues” (Jan. 8), cornetist Freddie Keppard’s first recordings with Doc Cook’s Dreamland Orchestra (Jan. 21), cornetist Muggsy Spanier and clarinetist Volly DeFaut romping on seven numbers with the Bucktown Five (Feb,. 28), the Georgians (a group with trumpeter Frank Guarante and pianist Arthur Schutt) recording “Mindin’ My Bus’ness” and “I You’ll Come Back” (Mar. 7), the Coon-Sanders Original Nighthawk Orchestra featuring what was arguably jazz’s first jazz vocal group (Carleton Coon and Joe Sanders) on “Red Hot Mama” (Apr. 6), cornetist Wild Bill Davison debuting with the Chubb-Steinberg Orchestra (April 10), bass saxophonist Adrian Rollini recording with the California Ramblers for the first time on “Copenhagen” and “Gotta Getta Girl” (Oct. 23) and, from an Okeh field trip to St. Louis, four hot numbers by cornetist Wingy Manone with the Arcadian Serenaders in St. Louis (Nov. 29) and two from Charlie Creath’s Jazz-O-Maniacs (Dee. 7)

100 years later, most of these recordings from 1924 still sound fresh and lively. The best jazz is always timeless.

Since 1975 Scott Yanow has been a regular reviewer of albums in many jazz styles. He has written for many jazz and arts magazines, including JazzTimes, Jazziz, Down Beat, Cadence, CODA, and the Los Angeles Jazz Scene, and was the jazz editor for Record Review. He has written an in-depth biography on Dizzy Gillespie for AllMusic.com. He has authored 11 books on jazz, over 900 liner notes for CDs and over 20,000 reviews of jazz recordings.

Yanow was a contributor to and co-editor of the third edition of the All Music Guide to Jazz. He continues to write for Downbeat, Jazziz, the Los Angeles Jazz Scene, the Jazz Rag, the New York City Jazz Record and other publications.