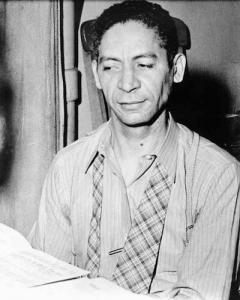

Jelly Roll Morton was a towering figure in early jazz, and one with a very large number of accomplishments. As a pianist who had his own easily recognizable style, Morton was a major transition figure between ragtime and early jazz, combining the syncopations of ragtime with jazz improvisations as early as 1910.

Jelly Roll Morton was a towering figure in early jazz, and one with a very large number of accomplishments. As a pianist who had his own easily recognizable style, Morton was a major transition figure between ragtime and early jazz, combining the syncopations of ragtime with jazz improvisations as early as 1910.

As jazz’s first significant composer, he wrote such songs as “King Porter Stomp,” “Milenburg Joys,” “Wolverine Blues,” “The Pearls,” “Grandpa’s Spells,” “Mr. Jelly Roll,” “Shreveport Stomp,” “Black Bottom Stomp,” “Winin’ Boy Blues,” “The Crave,” “Don’t You Leave Me Here,” “Sweet Substitute.” and “Wild Man Blues.”

As an innovative arranger, his best recordings made superb use of the three-minute limitations of 78s, utilizing dynamics, two and four-bar breaks, arranged passages, jammed ensembles, and solos that alternated between being written-out and improvised. Listeners often did not know if the music they were hearing was worked out in advance or spontaneous because the solo passages were a logical extension of the ensembles and vice versa.

Morton was one of the first jazz singers although unfortunately he only recorded one vocal (“Doctor Jazz”) in the 1920s. He was also an important bandleader who inspired several of his sidemen (such as cornetist George Mitchell and trombonist Geechie Fields) to do their finest work for him.

So why is Jelly Roll Morton still considered one of the most controversial of the early jazz greats? His consistent bragging and sometimes arrogant personality did him more harm than good. While someone like Willie “The Lion” Smith could get away with bragging and be considered lovable, Morton’s resulted in him having many detractors who greatly downplayed his talents, including some of his fellow musicians (such as Duke Ellington) and writer Leonard Feather.

He developed an overconfident front that he considered a necessity in order to make a living during hard times in his early life. Morton made some outlandish claims about his accomplishments that resulted in some of his contemporaries completely writing him off as if he were a fraud. But, as it turned out, much of what he said about his talents, career, and misfortunes was actually true.

Ferdinand Joseph La Mothe was born October 20, 1890, in Gulfport, Louisiana. His father, who was a bricklayer, left his mother (they were never married) when he was three. The following year when she married William Mouton, young Ferdinand took his stepfather’s last name.

He always loved music and, after stints on guitar and trombone, settled on the piano when he was ten. At 14, he began working as a pianist at a brothel in Storyville, renaming himself Jelly Roll Morton to avoid being discovered. However the deception was unsuccessful and, after his grandmother found out where he was spending his nights, he was disowned by his family.

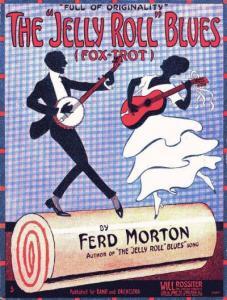

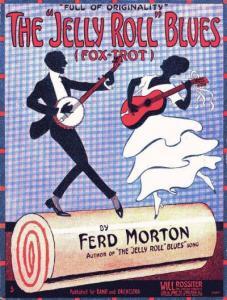

Morton, who composed “Jelly Roll Blues” in 1905 and soon followed with “Frog-I-More Rag” and “King Porter Stomp,” toured the South with minstrel shows. He made early appearances that helped to introduce blues and jazz to Chicago in 1910, New York City in 1911, and San Francisco in 1915. During that period, he also worked at a variety of other jobs including as a pool hustler, boxing promoter, tailor, gambling house manager, hotel manager, pimp, comedian in traveling vaudeville shows, and (whenever possible) pianist.

These were tough times and Morton developed both his personality and his music, fighting hard to survive and occasionally even prosper. He was mostly based in Los Angeles during 1917-22 but also spent time performing in Alaska, Wyoming, Colorado, Tijuana, and Vancouver, British Columbia.

In 1923 Morton moved to Chicago and began his recording career. While the 32 year old’s very first recordings were a couple of primitively recorded band sides, he made his mark that year with a series of brilliant piano solos, among the most significant in jazz up to that point.

The 19 solos (13 of which were cut in 1924) included “King Porter Stomp,” “Grandpa’s Spells,” “Kansas City Stomps,” “The Pearls,” “Shreveport Stomp,” “Jelly Roll Blues,” and a song that had already caught on with other groups, “Wolverine Blues.”

Later many of these songs would be transformed into band pieces; one can hear the pianist emulating full bands in the performances. Also in 1923, Morton recorded four numbers with the New Orleans Rhythm Kings including his “Milenburg Joys” and “Mr. Jelly Lord” on two sessions that are among the earliest integrated jazz dates.

While Morton’s early band recordings of 1923-24 are generally disappointing and a bit odd (his April 1924 session with his Stomp Kings finds him overseeing two kazoos and a comb player who was not on the level of Red McKenzie), he did make some excellent piano rolls in 1924 and recorded two duets (“King Porter Stomp” and “Tom Cat Blues”) with King Oliver, the only time that he teamed up with the cornetist.

Other than two excellent if often-overlooked duets with clarinetist Volly de Faut (“My Gal,” which also had Buddy Burton on kazoo, and “Wolverine Blues”), Morton was off records in 1925, mostly touring with bands in the Midwest and not actually working in Chicago that often.

While 1926 featured Morton in top form on a solo piano date, two so-so performances with groups from the road, and on a session accompanying Edmonia Henderson (including the introduction of his “Dead Man Blues”), the year is most notable for the beginning of his classic sides for the Victor label with his Red Hot Peppers.

Utilizing cornetist George Mitchell, trombonist Kid Ory, and his favorite clarinetist Omer Simeon as the frontline on three sessions starting on September 15, Morton recorded definitive versions of such pieces as “Black Bottom Stomp” (which seems to change its instrumentation, rhythms, and lead voice every eight bars), “The Chant,” “Sidewalk Blues,” “Dead Man Blues,” “Grandpa’s Spells,” “Doctor Jazz,” “Original Jelly Roll Blues” and “Someday Sweetheart.” The latter found a reluctant Simeon on bass clarinet while backed by two violins, one of the very first “jazz with strings” recordings.

1927 would result in such great Morton sides as “Wild Man Blues” (which he co-composed with his admirer Louis Armstrong), the one-chord “Jungle Blues,” and “The Pearls.” In addition, Morton performed trio versions of “Wolverine Blues” and “Mr. Jelly Lord” with clarinetist Johnny Dodds and drummer Baby Dodds.

Little did the pianist-composer know that he had hit the peak of his career although he still had some glory years left. Morton followed much of the jazz world by moving to New York in February 1928. He recorded a fine date as a sideman to cornetist Johnny Dunn and his first New York session as a leader had him utilizing Mitchell, Simeon and Geechie Fields on a memorable set of his songs including “Georgia Swing,” “Kansas City Stomps,” and “Mournful Serenade.” His hard-swinging yet complex number “Shreveport Stomps” made for a memorable trio showcase for Simeon and drummer Tommy Benford.

But from that point on, Morton would have difficulty putting together ideal groups in New York and his band recordings became a bit erratic. Some of the local musicians did not want to play with him due to his bragging and, while he used some top-notch soloists, most notably clarinetist Albert Nicholas, and trumpeters Bubber Miley, Ward Pinkett, and Henry “Red” Allen, some of his other sidemen were not worthy of him. On “Burnin’ The Iceberg,” the 11-piece orchestra almost gets completely out of control. Still, Morton did introduce such numbers as “Red Hot Pepper Stomp,” “Tank Town Bump,” “Fussy Mabel,” and “Strokin’ Away.”

However by 1930, Jelly Roll Morton was thought of as fading in importance and old-fashioned, particularly in comparison to Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong. His personality resulted in him burning bridges that he would soon need.

With the rise of the Depression and the collapse of the record industry, Morton’s Victor contract was not renewed after his session of October 9, 1930. Other than a guest spot on two songs for a Wingy Manone date in 1934 (which gave him his only opportunity to record with Manone, Artie Shaw, and Bud Freeman), the pianist would be off records altogether until 1938.

Morton picked up what jobs he could find in New York, was part of a band in a traveling burlesque act, and briefly had a radio show in 1934, but he was largely forgotten by the jazz world. In 1935 he moved to Washington D.C. where he played piano and managed a bar that was known as the Music Box, later renamed the Blue Moon Inn and the Jungle Inn.

One can only imagine his state of mind, having been ripped off by publishers who paid him little or no money in royalties, when he heard his “King Porter Stomp” being played regularly on the radio. Benny Goodman had his first hit with that song and it became a regular part of many big bands’ repertoire while its composer was toiling in obscurity and poverty. “Wolverine Blues,” and “Milenburg Joys” were also standards but few cared about its composer who was playing music and tending bar for indifferent customers.

In March 1938, Jelly Roll Morton became incensed by a Ripley’s Believe It Or Not radio program on which W.C. Handy was introduced as the originator of jazz, stomps, and blues. Morton, who never cared for Handy, saw him as a mediocre cornetist who could not improvise and had made a fortune by writing down blues songs performed by others and publishing them under his own name. Morton wrote a famous letter that was published in Downbeat.

In March 1938, Jelly Roll Morton became incensed by a Ripley’s Believe It Or Not radio program on which W.C. Handy was introduced as the originator of jazz, stomps, and blues. Morton, who never cared for Handy, saw him as a mediocre cornetist who could not improvise and had made a fortune by writing down blues songs performed by others and publishing them under his own name. Morton wrote a famous letter that was published in Downbeat.

While most of what he said about his life and career was true, it contained this sentence: “It is evidently known, beyond contradiction, that New Orleans is the cradle of jazz, and I, myself, happened to be creator in the year 1902”. The full letter is quite fascinating. Morton, who later in life claimed to have been born in 1885 so as to bolster his 1902 claim, was actually only 12 that year and had been preceded by Buddy Bolden (who he called a ragtime musician) and others.

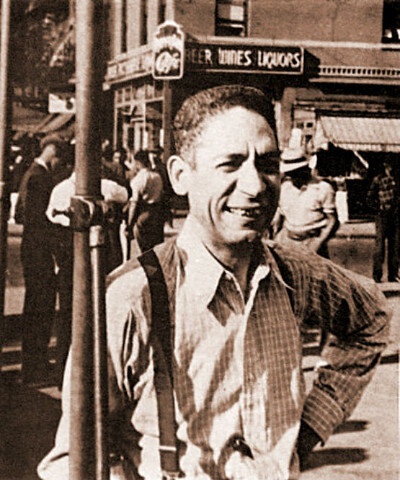

While the letter has led to Morton being ridiculed by some, it got the attention of Alan Lomax of the Library of Congress. From May to July, 1938, Lomax interviewed Morton extensively about the early days in New Orleans and the results, which find Jelly Roll not only telling stories but playing and singing extensively for over eight hours, add greatly to what is known about the unrecorded beginnings of jazz.

Most notable was Morton’s musical examples of how “Tiger Rag” (which he claimed to have composed) was gradually turned into jazz, and his contrasts of “Maple Leaf Rag” as straight ragtime and the way that he played it. Quite typically, Morton was never paid for all of this work and the priceless performances and reminiscences were not made available to the public until after Morton’s death, but it lifted his spirits and led to him becoming determined to make a comeback.

While not quite completed with the Library of Congress sessions, Morton was stabbed at the Music Box. A nearby white hospital turned him away and the treatment that he received at a black hospital was inadequate; he would never fully recover. For his final Library of Congress session, Morton accompanied his talking and singing on guitar although he would soon be able to play piano again.

In 1939, Jelly Roll Morton returned to New York. While there had been a few mostly poorly recorded live recordings made in Baltimore the previous year (including one brief piece where he played organ), these two New York sessions, which include such notables as trumpeter Sidney DeParis, Sidney Bechet, and clarinetist Albert Nicholas, were his official return to records.

They are highlighted by his compositions “Buddy Bolden Blues” (also known as “I Thought I Heard Buddy Bolden Say”) and “Winin’ Boy Blues.” He also recorded three excellent sessions of piano solos showing that he was still in his musical prime.

When those records did not sell well, Morton in 1940 wrote new material that he hoped would generate a hit, recording a dozen selections with a fine group that included Nicholas and Henry “Red” Allen.

Unfortunately such songs as “Good Old New York,” “Swinging The Elks,” and “My Home Is In A Southern Town” did not catch on. The final documentation of Morton was a radio broadcast on July 14, 1940, with the NBC Chamber Music Society of Lower Basin Street which resulted in a band version of “Winin’ Boy Blues” and an excellent rendition of “King Porter Stomp” (which had been his first recorded piano solo almost exactly 17 years earlier) as a duet with drummer Nat Levine.

Unfortunately such songs as “Good Old New York,” “Swinging The Elks,” and “My Home Is In A Southern Town” did not catch on. The final documentation of Morton was a radio broadcast on July 14, 1940, with the NBC Chamber Music Society of Lower Basin Street which resulted in a band version of “Winin’ Boy Blues” and an excellent rendition of “King Porter Stomp” (which had been his first recorded piano solo almost exactly 17 years earlier) as a duet with drummer Nat Levine.

In late 1940, a frustrated and ill Jelly Roll Morton drove with all of his belongings to California. He hoped to get a fresh start and put together a new band. He wrote a few new tunes including the adventurous “Ganjam” and rehearsed some musicians but his health quickly declined from asthma and a heart condition. On July 10, 1941, he passed away at the age of 50.

Unlike in his music, Jelly Roll Morton’s life had suffered from consistently bad timing. If he had survived another few years, he would certainly have been a major part of the New Orleans jazz revival movement. The music of Jelly Roll Morton music has been performed on a nightly basis ever since his passing and posthumously he has received the recognition that he deserved in his lifetime.

Browse hundreds of his recordings in the Red Hot Jazz Archive

Since 1975 Scott Yanow has been a regular reviewer of albums in many jazz styles. He has written for many jazz and arts magazines, including JazzTimes, Jazziz, Down Beat, Cadence, CODA, and the Los Angeles Jazz Scene, and was the jazz editor for Record Review. He has written an in-depth biography on Dizzy Gillespie for AllMusic.com. He has authored 11 books on jazz, over 900 liner notes for CDs and over 20,000 reviews of jazz recordings.

Yanow was a contributor to and co-editor of the third edition of the All Music Guide to Jazz. He continues to write for Downbeat, Jazziz, the Los Angeles Jazz Scene, the Jazz Rag, the New York City Jazz Record and other publications.