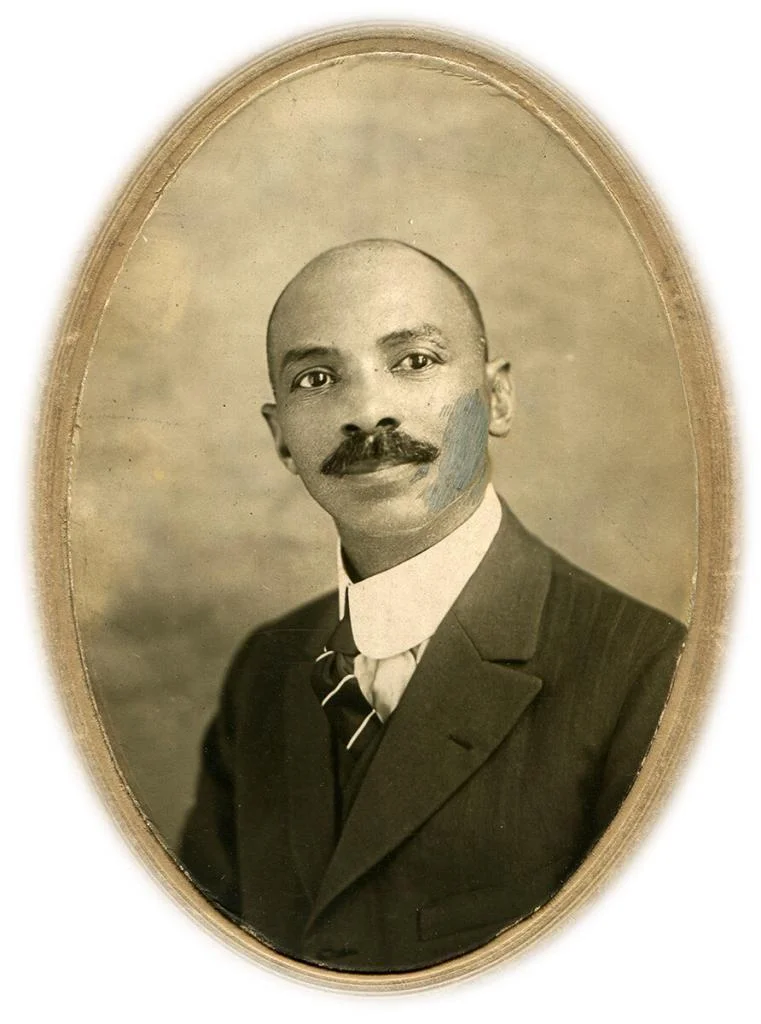

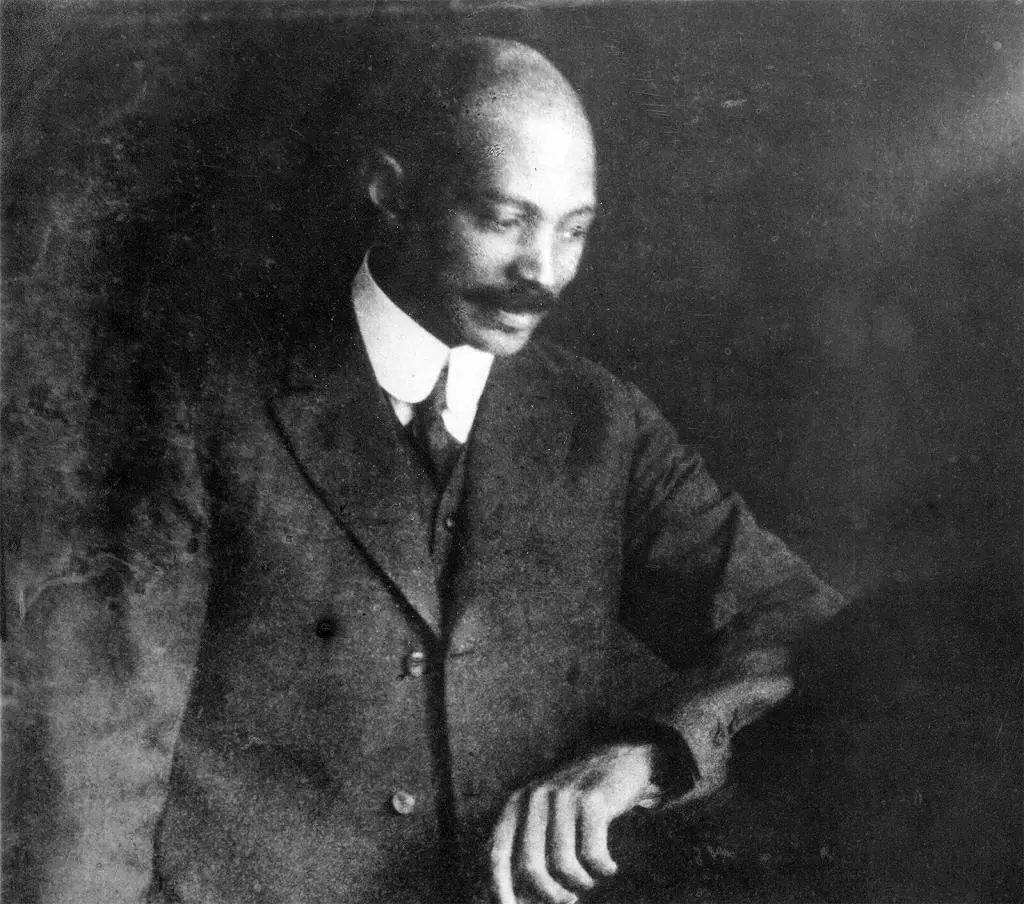

The music, words and voice of William Christopher Handy (1873-1958) reveal his passion for Blues music and African American culture. He was one of the earliest gathering and preserving the oral and aural folk-Blues that he successfully incorporated into his songwriting after 1912. He dedicated his life to the proposition that the Blues are a legitimate and vital musical form during an era when that idea was rejected or ridiculed.

Wherever possible Handy’s own words and voice have been used to convey his story. Many of the photos are newly available courtesy of the W.C. Handy Museum and Home in Florence, Alabama thanks to Joanne Fish, producer of the documentary, Mr. Handy’s Blues. This column and the audio clips are based on the Gabriel Broadcast Award-winning radio program, W.C. Handy Remembers.

A Monumental American

Whether they know it or not, most Americans know and love the music of W. C. Handy. His lovely “Memphis Blues” and “Yellow Dog Blues” are still popular. A touchstone of American culture, “St. Louis Blues” was the most recorded jazz composition in the early 20th Century.

Handy was variously a travelling minstrel, cornet player, bandleader, promoter, folklorist, composer, music publisher, campaigner for civil rights and cultural icon. He developed a keen skill for creating great music by fusing his own gift for composing with the lyrical and idiomatic fragments he gathered. His best-known songs like “Careless Love,” “Beale Street Blues” and “Atlanta Blues” were crafted from the raw folkloric elements he dedicated his life to collecting, compiling and interpreting. In interviews, articles and his autobiography, Handy took great care to acknowledge his mostly anonymous folk sources.

Clip A – Introduction and Yellow Dog Blues

Handy on culture:

“When we take these things of our own and develop them till they are the fine things, I think that’s pure culture. You’ve got to appreciate the things that come from the heart of the negro and from the heart of the man farthest down.”

“The great European classics came from the peasantry of the countries in which these people lived. It didn’t come from the kings and queens and the great theaters. It came from the man who dug deep into the hearts of the people he had come up with and loved, the man farthest down.”

Early Years

Born to a former slave in Alabama less than a decade after the Civil War, William Christopher Handy was the son and grandson of Methodist (AME) ministers. Overcoming resistance from his family and society, he gained a thorough musical education and made his living as a professional musician. During the 1890s, he was a wandering trumpet player (cornet, in the early days).

W. C. Handy eventually led his own ensembles, writing and arranging music. Becoming a beloved bandleader in Memphis, Tennessee, he began publishing his own songs. He was very probably the first to make a livelihood printing and selling the Blues as sheet music, initiating a long struggle to legitimize the form. During decades of roaming, Handy collected fragments of lyrics, melodies, folk songs, spirituals and work songs, netting like rare butterflies what would otherwise surely have been lost.

Clip B – Memphis Blues by Handy

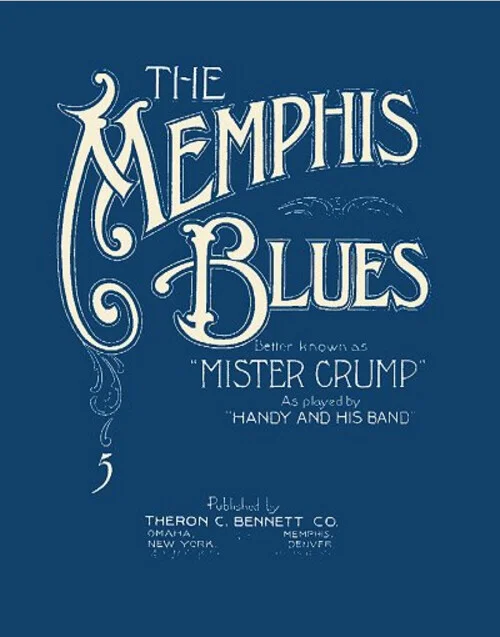

The Memphis Blues

In 1909 his band was hired to play for the mayoral campaign of Memphis political boss, Edward H. Crump. According to Handy, he won the election thanks in part to the popularity of his song known as “Mr. Crump.” Though the politician ran on a reform platform opposing vice and corruption, once he was elected both flourished.

In 1909 his band was hired to play for the mayoral campaign of Memphis political boss, Edward H. Crump. According to Handy, he won the election thanks in part to the popularity of his song known as “Mr. Crump.” Though the politician ran on a reform platform opposing vice and corruption, once he was elected both flourished.

Three years later, Handy put it out as “The Memphis Blues” with new lyrics provided by Mr. George Norton. It was among the very first published Blues songs and a big hit across the country, formally introducing his style of 12-bar blues.

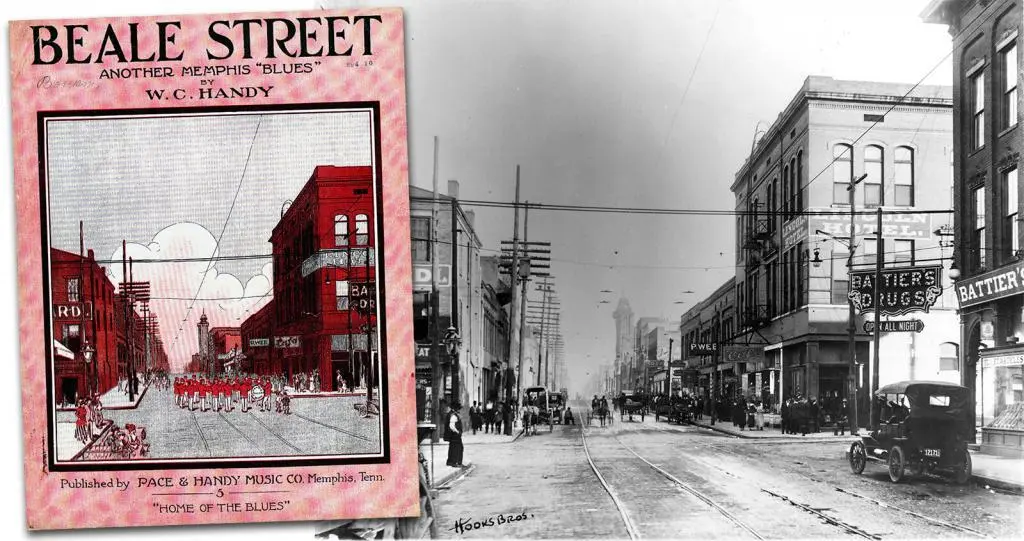

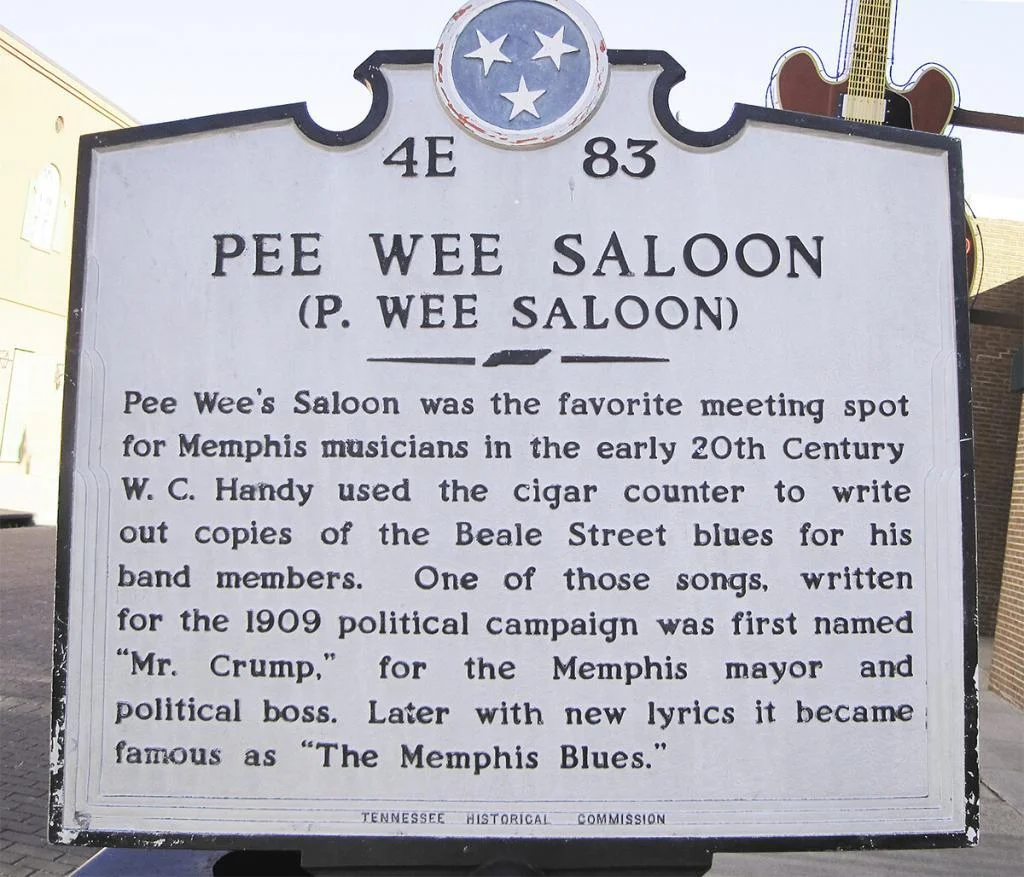

The great success of “The Memphis Blues” in 1912 prompted Handy to form his own company on Beale Avenue in Memphis. From 1913 to 1918, Pace & Handy Music Company published his most popular songs including “St. Louis Blues,” “Yellow Dog Blues” and “The Beale Street Blues,” before moving their publishing office to New York City.

The Beale Street Blues

Memphis was a thriving transportation hub at the junction of the railroads and the Mississippi River. Developing after the Civil War, the original Beale Avenue was a respectable, predominantly African American neighborhood of homes, churches and a grand opera house. By the time Handy arrived around 1910, Memphis had sprouted the notorious entertainment district, an infamous collection of taverns, pool rooms, dance and gambling halls, brothels and dives.

The lawless ‘Beale Street’ section contained hustlers, pickpockets, lowlifes, pimps and prostitutes. It attracted country rubes seeking thrills and workingmen — riverfront roustabouts, levee workers, cotton farmers and Pullman porters — out spending their hard-earned pay. Thriving in the rough nighttime traffic of the rowdy quarter, Handy was oddly fascinated, possibly even obsessed by Beale Street where he observed razor fights, stabbings, ice pick killings, shootings and worse.

Writing the Beale Street Blues:

Writing the Beale Street Blues:

“I like the life of Beale Street. It was exciting. So much so that I was two years trying to write a number called Beale Street, but I couldn’t find words for it.

One night, after leaving my office, I passed by Pee Wee’s saloon. Next to it was a barbershop. This barbershop was open, say about 2:00 o’clock in the morning. I said, ‘c’mon let’s go home.’ He says, ‘I haven’t closed up cause ain’t nobody got killed yet.’ And I struck myself and said that’s it, Beale Street Blues! I went home and wrote the words to the Beale Street Blues that night.”

You’ll see pretty browns in beautiful gowns,

You’ll see tailor-mades and hand-me-downs,

You’ll meet honest men, and pick-pockets skilled,

You’ll find that business never ceases ’til somebody gets killed!

If Beale Street could talk, if Beale Street could talk,

Married men would have to take their beds and walk,

Except one or two who never drink booze,

And the blind man on the corner singing Beale Street Blues!

Clip C – Beale St Blues, Yellow Dog Blues

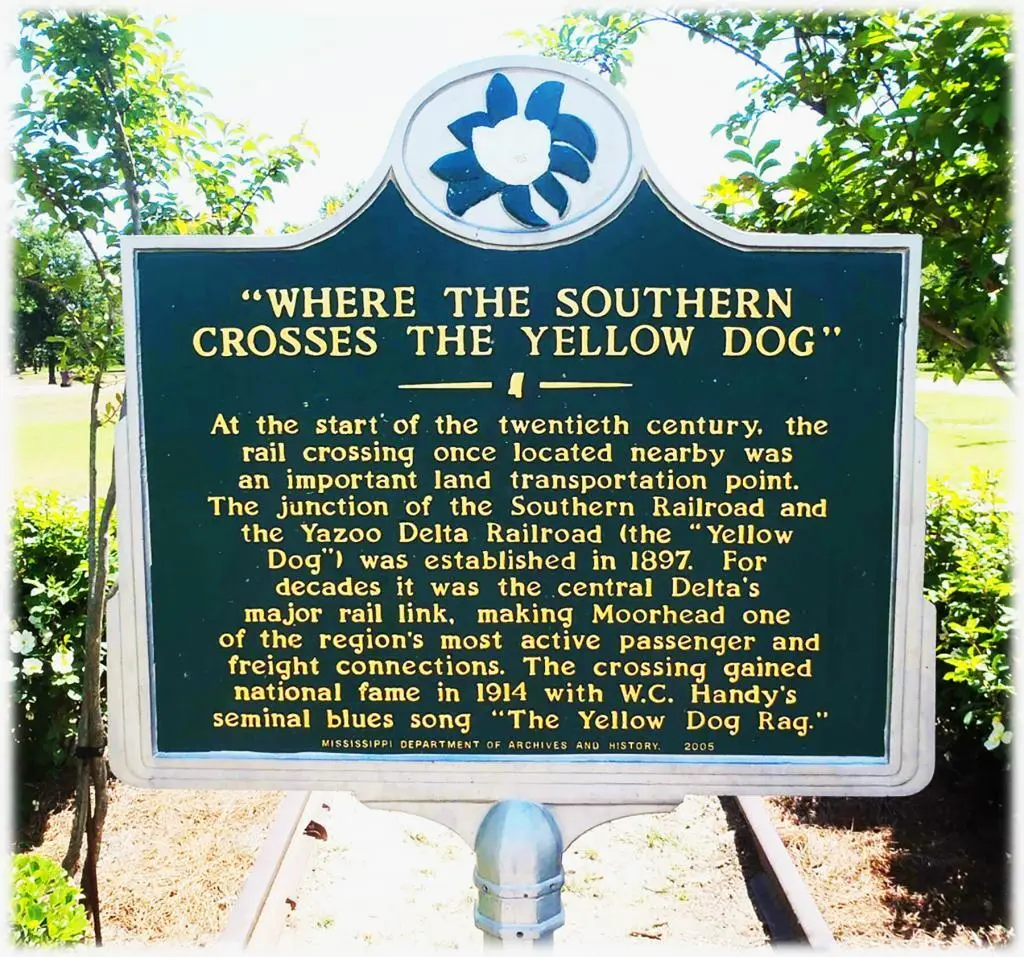

The Yellow Dog Blues

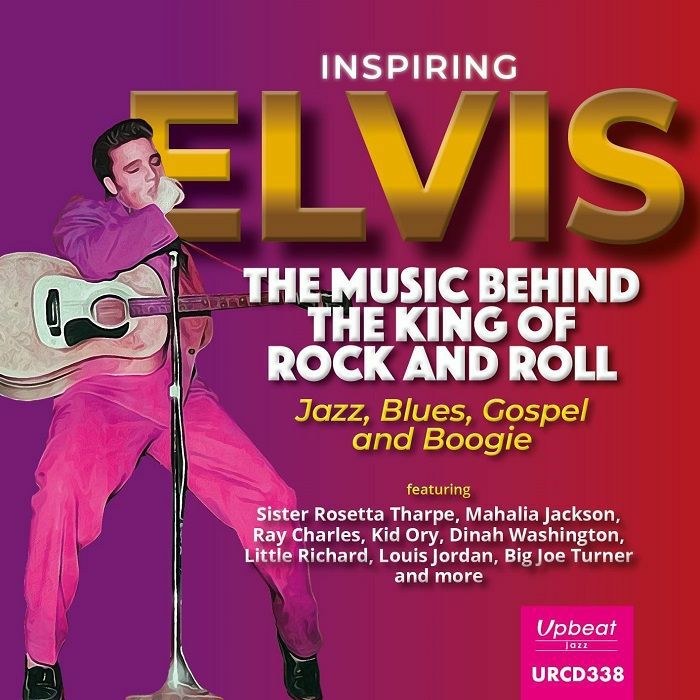

W. C. Handy published the “Yellow Dog Blues” to great success in 1914. One of his simplest and most enduring songs, it highlights his remarkable skill at carving poetry from the vernacular. He heard an itinerant singer playing it on a slide guitar in a rural railroad station — a galvanizing early encounter with the Blues.

The song tells the tale real or imagined of Miss Susie Johnson lamenting that her “easy rider” (lover, pimp or gigolo) ran off. The frantic search elicits a letter informing her that he “struck this burg today,” but had left and gone to “where the Southern cross the Yellow Dog.”

Commentary on Bessie Smith’s Yellow Dog Blues by Dan Radlauer

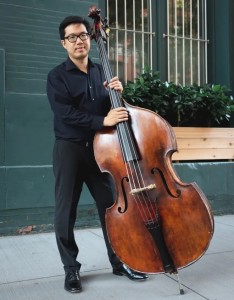

For a deeper look I’ve asked an accomplished musician, my brother Dan Radlauer, to assess the best-known rendition of “Yellow Dog Blues” by Bessie Smith, accompanied by Henderson’s Hot Six (aka Bessie Smith and her Blue Boys) recorded in New York on May 6, 1925.

For a deeper look I’ve asked an accomplished musician, my brother Dan Radlauer, to assess the best-known rendition of “Yellow Dog Blues” by Bessie Smith, accompanied by Henderson’s Hot Six (aka Bessie Smith and her Blue Boys) recorded in New York on May 6, 1925.

“The song starts with standard, predictable blues chord changes and evolves smoothly into some complex and rich variations on that chord progression. After the truncated blues form intro, where everyone in the band except the singer is playing, we launch into a very simple accompaniment behind Bessie Smith.

Twelve-bar Blues has become the primary “Blues” form, and this song is no exception. The hallmark of a Blues chord progression is the fifth measure. Various things can happen before or after that spot, but at that point the defining moment is going to the “IV” chord.

Here the cornet plays subtle fills and long notes, keeping the style and mood. The first two verses use the simplest of Blues Progressions. No superfluous chord changes. Just meat and potatoes Blues. Pretty much: I, IV, I, V, I, V.

Here the cornet plays subtle fills and long notes, keeping the style and mood. The first two verses use the simplest of Blues Progressions. No superfluous chord changes. Just meat and potatoes Blues. Pretty much: I, IV, I, V, I, V.

But at the third verse, all bets are off. Each subsequent verse gets more harmonically complex and sophisticated. The third verse uses a VERY unexpected chord at the 9th measure. I don’t think this would ever happen spontaneously. Either it was rehearsed, or there was a written “chart” to help everyone stay on the same harmonic page.

At about 2:30, listen for a descending line. This is a very distinctive moment and the band executes it beautifully. If you listen really close at 2:45, another special moment happens. The band has hit the important sign post of going to the IV chord in the fifth measure, but in the 6th measure, they switch that chord from a MAJOR chord, to a MINOR chord. While not unheard of, this is a wonderful little surprise and would most likely be planned ahead of time.

Meanwhile, Bessie sings the blues with no specific alterations reflecting the evolution going on in the band. She sticks primarily to the notes in the blues scale and brings her variations and special interpretation in her rhythmic delivery and vocal affectations. Meanwhile, the band is keeping themselves entertained by doing different variations on each consecutive verse and enjoying riffs and counter-melodies that reflect those variations. A great combination, making for a great recording.”

Aunt Hagar’s Blues

Originally entitled “Aunt Hagar’s Children Blues,” biblical and spiritual references are not uncommon in Handy’s music. An Egyptian from the Old Testament, Hagar was a female servant to Sarah, wife of Abraham. Because Sarah was barren she gave Hagar to Abraham as concubine, so he could sire a child.

Handy based it on a mournful musical motif he heard crooned by an anonymous washerwoman hanging clothes out to dry one cold night. Originally conceiving it as a much sadder slower dirge, he asserted that “negroes often spoke of themselves as Aunt Hagar’s children.”

Just hear Aunt Hagar’s children harmonizin’ to that old mournful tune,

It’s like a choir from on high broke loose,

If the debbil brought it the good Lawd sent it right down to me,

Let the congregation join while I sing those lovin’ Aunt Hagar’s Blues.

Clip E – Aunt Hagar’s Children’s Blues

Joe Turner’s Blues

In “Joe Turner’s Blues” Handy exposed the shameful practice of entrapping and kidnapping black men for work gangs. The brother of a one-time Tennessee governor, Joe Turney (later, Turner) was infamous for falsely arresting African American men, often by luring them to crap games.

Turney would chain together up to eighty prisoners for delivery to penitentiaries or work farms or in the South. But this subject was so distressing that Handy re-published the song with a new lyric concealing and censoring its original and true meaning.

Imprisonment of this kind was backstory for the main character in August Wilson’s 1988 play, Joe Turner’s Come and Gone. According to Handy, a wife asking about her missing husband might be told, “Haven’t you heard about Joe Turner? He’s been here and gone.”

Handy sings Joe Turner’s Blues during an interview late in life.

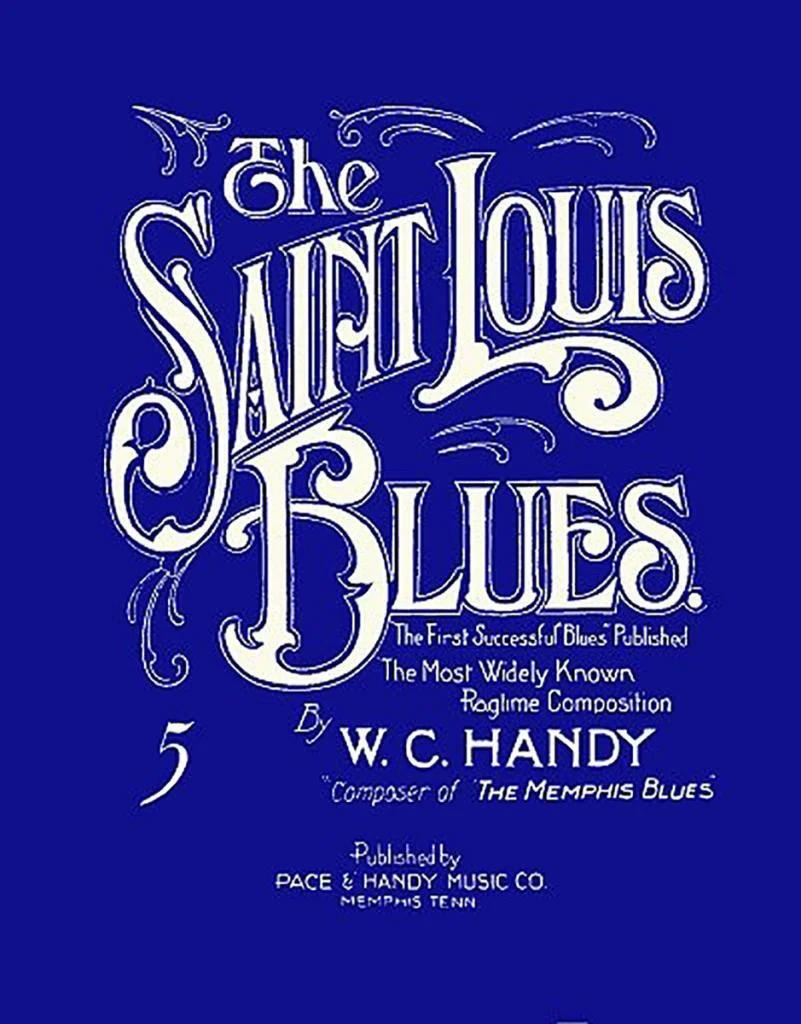

The Saint Louis Blues

“Saint Louis Blues” was by far Handy’s biggest hit. Published in 1914, it made the top-20 song charts twenty-one times before 1948, earning him a handsome lifelong income and world-wide fame. And for instance, Brian Rust’s Jazz Discography: 1897-1942 lists almost twice as many recordings for “Saint Louis Blues” than for any other song, making it the most recorded tune of early Jazz.

“Saint Louis Blues” was by far Handy’s biggest hit. Published in 1914, it made the top-20 song charts twenty-one times before 1948, earning him a handsome lifelong income and world-wide fame. And for instance, Brian Rust’s Jazz Discography: 1897-1942 lists almost twice as many recordings for “Saint Louis Blues” than for any other song, making it the most recorded tune of early Jazz.

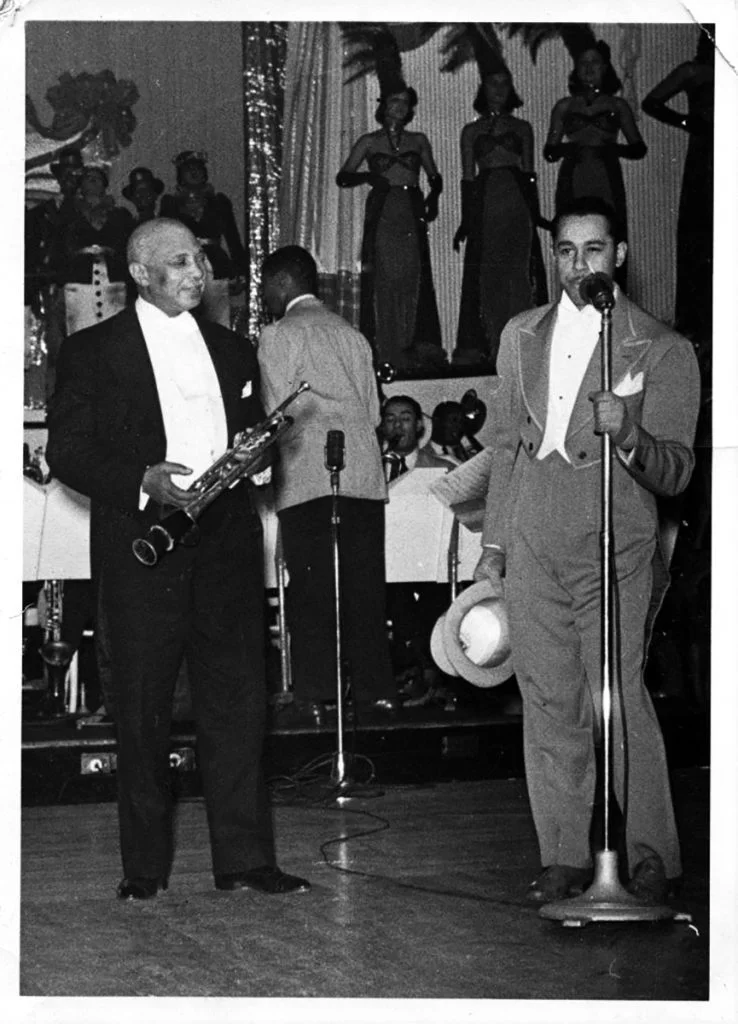

Several notable movies were named for the song. A short film featuring Bessie Smith in 1929 contains her only moving images. A 1939 musical starred Dorothy Lamour. In 1958, the year Handy died, singer Nat “King” Cole starred in a major motion picture playing the role of Mr. Handy and released an album of his songs. By one estimate, “Saint Louis Blues” was used as a music cue or motif in some 400 films.

Like so many of Handy’s songs, it was inspired by real life. He’d heard one of the melodic strains and the phrase, “that man got a heart like a rock cast in the sea” on the streets of Saint Louis, Missouri two decades earlier. Yet the composer made clear that the words were his own and based on personal experience. “If you’ve ever slept on cobblestones or had nowhere to sleep you can understand why I began this song with, ‘I hate to see the evening sun go down’.”

Clip F – St Louis Blues Pt. 1

Clip G – St. Louis Blues Pt. 2

‘I’ve Seen the Lights of Gay Broadway’

The publishing office of Harry Pace and W.C. Handy on Broadway near Times Square was at the crossroads of the booming New York entertainment district. Around 1920, Handy and Pace were at the cutting edge of African American entertainment and popular culture; their business office a nexus of intellectual ferment.

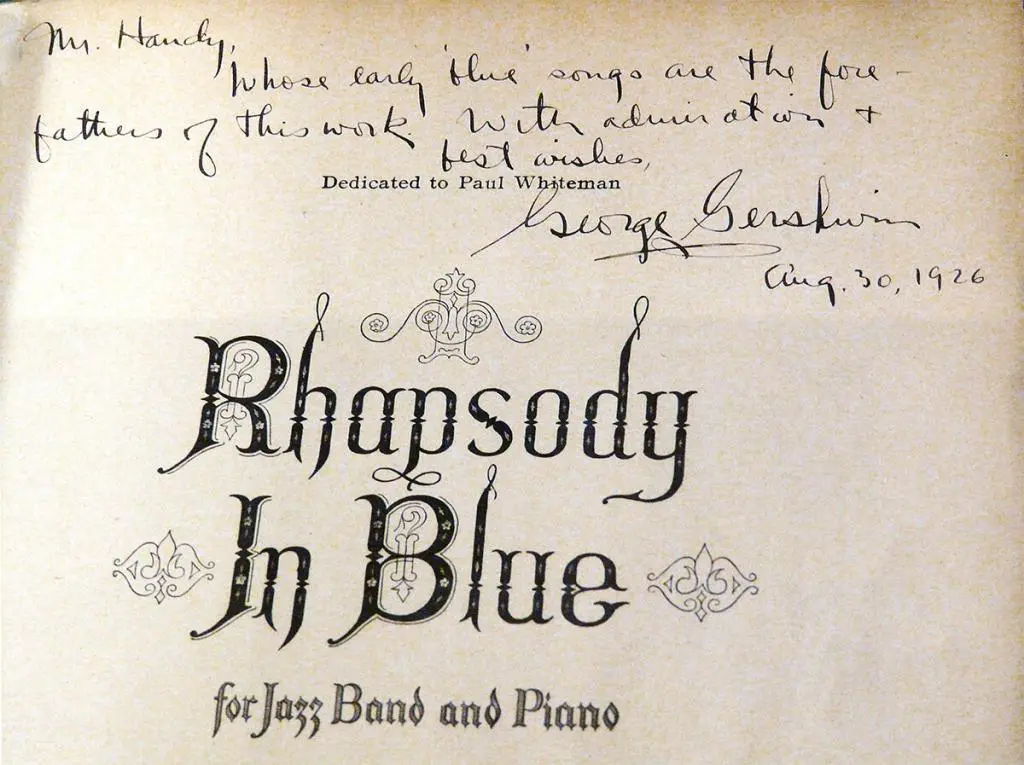

Handy consorted with noteworthy artists, intellectuals of the Black consciousness movement and wrote songs with Langston Hughes, poet laureate of the Harlem Renaissance. His broad circle of collaborators encompassed singers Sophie Tucker, Eddie Cantor, Al Jolson and composer George Gershwin — who considered him a mentor.

But Handy was hit by a devastating loss in 1921 when he was double-crossed by his partner and close friend, Harry Pace. Departing suddenly, Pace took most of their best artists, founding Black Swan Records, the first African American owned and operated record company.

But Handy was hit by a devastating loss in 1921 when he was double-crossed by his partner and close friend, Harry Pace. Departing suddenly, Pace took most of their best artists, founding Black Swan Records, the first African American owned and operated record company.

Pace was a bold innovator but at his former partner’s expense, appropriating the partnership’s best artists, music and key staff, including pianist Fletcher Henderson and composer William Grant Still. Handy never fully recovered from the financial, professional and personal loss.

Folklorist of the Blues

A pioneering folklorist, Handy made one of the earliest attempts to document and interpret the folk-Blues. He deserves high praise for being the first to fruitfully publish and disseminate the Blues in written form, authoring many durable classics. Unlike an observer from outside the culture, he was a participant with access and insight, using the raw materials of African American life for his art as did Duke Ellington and writers Zora Neal Hurston or James Baldwin.

It is somewhat unfortunate that Handy embraced the moniker “Father of the Blues.” Because as he himself often stressed, Blues was the offspring of numerous mothers and fathers, many anonymous or long forgotten.

The composer has occasionally been accused of exploiting the Blues by claiming authorship of songs which were not wholly his own. Envious of his vast success, Jelly Roll Morton set this spurious criticism loose in the late 1930s. Yet Handy freely acknowledged that lots of his melodies and lyrics were not strictly his own original ideas, but that he was recording the music, stories and culture of his people.

W. C. Handy’s 150 settings of Blues, Folk and Spiritual themes demonstrate a keen talent for crafting enduring themes from passing motifs that otherwise would have been lost. In that respect, he was not unlike the classical composers Mozart, Beethoven, Dvorak, Liszt or Bartok who borrowed freely from the folk cultures around them.

CLIP H – Handy on Culture, Hesitation Blues

Mr. Handy’s Blues – Documentary DVD

For a more complete and intimate view of this monumental musician, I can recommend Mr. Handy’s Blues. It’s a rich chronicle of his life and music, telling his story with high production values and modern documentary techniques. It traces his story through minstrel shows and touring orchestras, the Memphis-Beale Street years, his role in the transition from Ragtime to Jazz and ascension to American greatness.

There is no comparable source offering a more visceral account of his saga with commentary from a panoply of performers from Taj Mahal to Vince Giordano. It utilizes more than 100 archival images to trace Handy’s story — the majority were previously unknown to this writer. Producer Joanne Fish provided several of the photos seen here, courtesy of the W.C. Handy Home and Museum in Florence, Alabama.

Clip I – Conclusion Beale St by Ellington

Honored Elder Spokesman

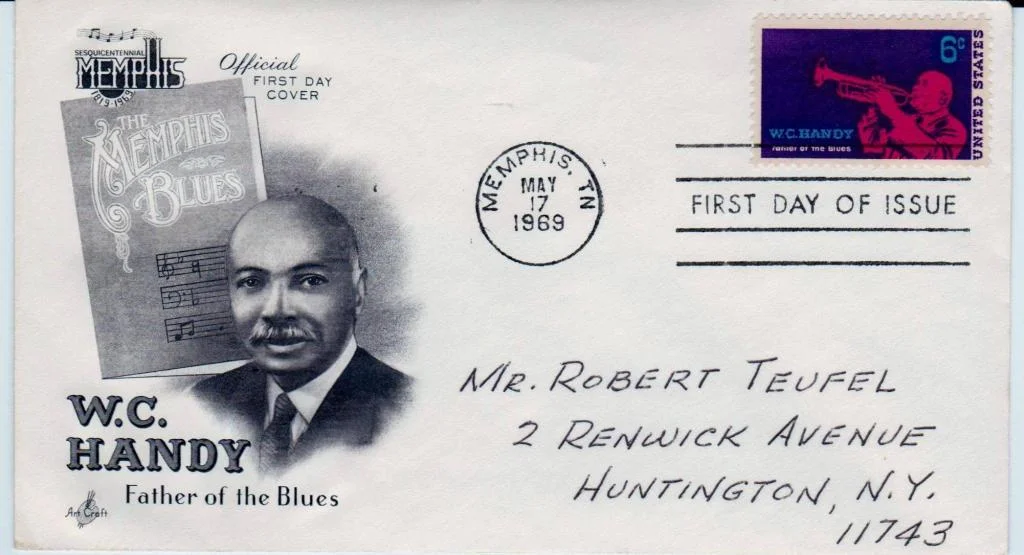

Among the innumerable tributes, honors and accolades awarded Handy were a 1928 concert of his music at Carnegie Hall; the City of Memphis dedicating a park (1936) and statue (1960); posthumous awards from the Grammys, Nashville Songwriter’s Association and multiple halls of fame.

A United States postage stamp bearing his likeness was issued in 1969. Today, numerous music festivals are held in W. C. Handy’s name. The largest is in Northwest Alabama near where he was born and raised, encompassing some 300 events.

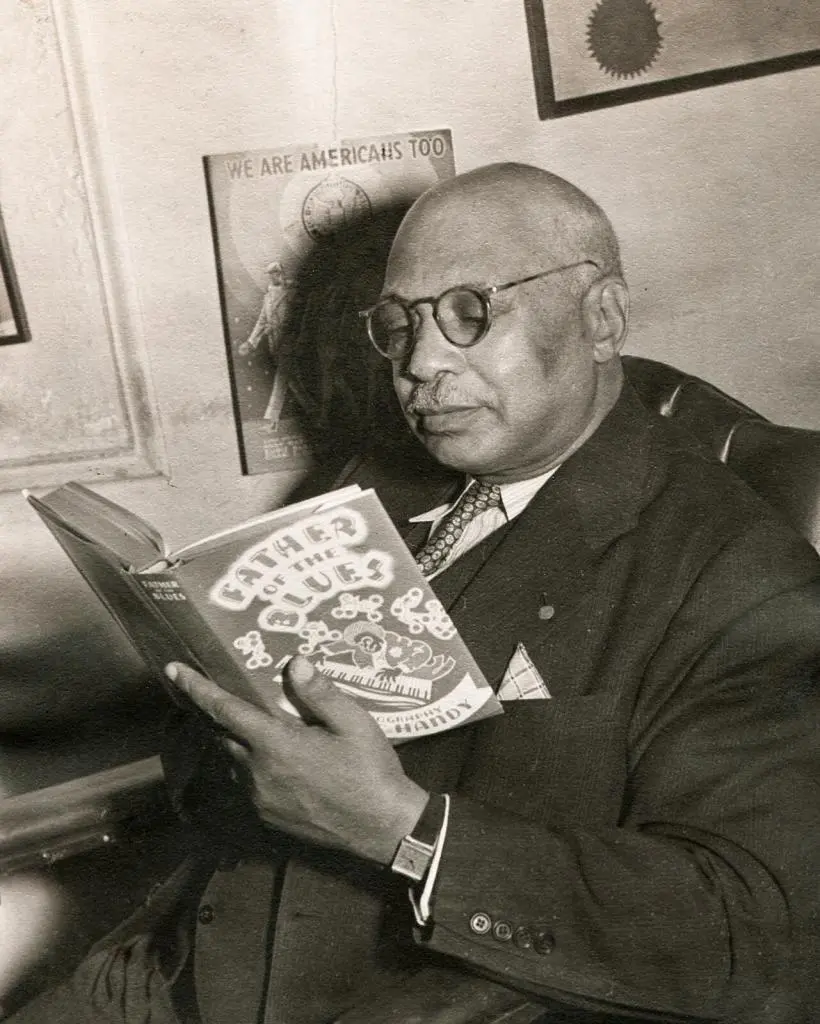

The high-profile publication of his autobiography Father of the Blues in 1941 brought Handy further prominence as a representative for African Americans in general. Approaching his seventh decade, W.C. Handy was widely recognized as a grand old man of American music, a leading advocate for the Blues and dedicated civil rights campaigner.

As the United States was girding to fight the Second World War, there was a growing emphasis on democratic American Roots culture — Blues, Spirituals and New Orleans Jazz — which were emerging from the periphery of American life. Handy neatly fit the mood, serving as an eloquent, passionate and vaguely saintly spokesperson for Black people.

William Christopher Handy probably did more than any other single person to popularize and legitimize Blues music during the first half of the Twentieth Century. Today he is cherished as a cultural icon, self-taught folklorist, pioneering African American entrepreneur and visionary composer.

To Comfort and Cheer:

“I’m thankful for being a part of the oppressed race . . . [and] through adversity was thrust down amongst the lowly. And took out of their hearts a song that caught the wings of the morning and fell on the world’s weary ear. And then found a place to comfort and cheer the heart of humanity.”

Reprise

As the Blues and Handy’s music were accepted into the mainstream of American culture, his compositions were increasingly heard on radio and recordings. Here are two examples from 1940; each were world premieres: Artie Shaw’s classic first-recording of “Chantez Le Bas” (Sing ‘em Low) and an excerpt from a Handy tribute that was broadcast on the NBC radio network by the Chamber Music Society of Lower Basin Street.

Clip J – Chantez Le Bas, Heist de Window, Noah

Thanks, Sources and Further reading:

Radio broadcasts courtesy of the Library of Congress, NBC Radio Collections. Thanks to Dan Radlauer for expert commentary and Dick Raichelson for selected audio clips. Great thanks to Joanne Fish for photos.

Father of the Blues, W.C. Handy (MacMillan, 1941)

JAZZ: A History of America’s Music, Geoffrey C. Ward (Knopf, 2000)

Jazz Records, 1897-1942, Brian Rust (Arlington House, 1978)

The Devil’s Music: A History of the Blues, Giles Oakley (Tapliner, 1976)