Before the rise of Miff Mole, Jimmy Harrison, and especially Jack Teagarden in the late 1920s, Edward “Kid” Ory was the most important influence on other jazz trombonists. His “tailgate” style featured him using his horn to play rhythmic bass lines and harmonies in the front line of freewheeling New Orleans jazz bands, behind the trumpet and clarinet.

While the trombone had been used as a comic foil in vaudeville where it slid all over the place and made humorous sounds, Ory was quite serious about his own playing. Once he had developed his style in the early days, he stuck throughout his career to the percussive role of the trombone, seeing no reason to “modernize” or alter his approach. Since he was a master at what he played and he had his own personal voice on his instrument, why he should try to copy other musical trends?

New Orleans

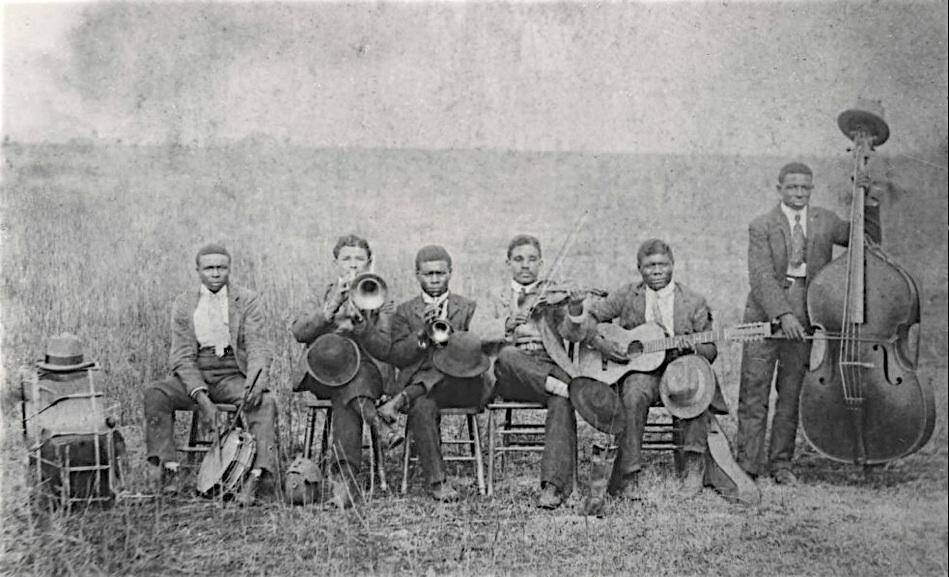

Kid Ory was born on Dec. 25, 1886, in La Place, Louisiana. He was very interested in music from an early age, performing with a singing group as a youth, and then a band in which the youngsters played homemade instruments. He started on the banjo when he was ten, soon switching to valve trombone and eventually permanently to slide trombone. During Ory’s first visit to New Orleans in 1905, his playing impressed Buddy Bolden so much that Bolden offered him a job. But due to family obligations (he had agreed to stay in La Place supporting the family until he was 21), Ory had to reluctantly turn him down.

As it was, Ory did not move to New Orleans until 1910. But soon after he relocated, he became one of the most important bandleaders in the city. Joe “King” Oliver was his cornetist for a time with Johnny Dodds as his clarinetist. This significant period in Ory’s career unfortunately was never recorded although one could guess what his band might have sounded like based on how Ory, Oliver, and Dodds sounded in the 1920s. His music featured blues and pop tunes, was ensemble-oriented, was always played at danceable tempos, and made expert use of dynamics. Other musicians who spent time in Ory’s band included clarinetists Jimmie Noone, Sidney Bechet, and George Lewis. In 1918 when Oliver left New Orleans to head up to Chicago, he recommended the young Louis Armstrong as his replacement.

Los Angeles

In 1919, Ory decided that he had accomplished all that he could on the New Orleans scene and he moved to California. When he found that there was an interest in New Orleans jazz, he sent home for players (including cornetist Mutt Carey) and was based in Los Angeles for the next six years. Ory’s combo also spent periods working in San Francisco and Oakland. In 1922 he had the opportunity to lead the first African-American New Orleans jazz band on record. As either Ory’s Sunshine Orchestra or Spike’s Seven Pods Of Pepper Orchestra (depending on the label), his group accompanied singers Roberta Dudley and Ruth Lee on two songs apiece and recorded the instrumentals “Ory’s Creole Trombone” and “Society Blues.” Five years after the Original Dixieland Jazz Band had made their first records, Ory’s band offered listeners an alternative brand of New Orleans jazz.

Chicago

While Kid Ory enjoyed being in California, playing at Hollywood parties and on the radio, by 1925 he realized that Chicago was the place to be for jazz musicians. Actually, if he had moved to Chicago in 1923, he probably would have been in King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band. When he made the decision to move, he gave his band to Carey and headed east. Ory had two jobs waiting for him in Chicago, playing nightly with King Oliver’s Dixie Syncopators and recording with Louis Armstrong’s Hot Five. He would be quite busy during the next four years.

Recordings

Even though he did not lead any record dates of his own in Chicago, it would be difficult to imagine the Chicago jazz scene of the 1925-28 period without Ory. As a member of Louis Armstrong’s Hot Five during 1925-27, his rhythmic style and gruff sound served as a perfect contrast to Armstrong. On such pieces as “Gut Bucket Blues,” “Come Back Sweet Papa,” “Jazz Lips,” a remake of “Ory’s Creole Trombone,” and his own “Savoy Blues,” Ory provided a perfect backdrop for Armstrong’s flights. He also had the chance to make the recording debut of his most famous original “Muskrat Ramble” on February 26, 1926. To show his importance in these recordings, when the trombonist was on tour with King Oliver and missed being part of Armstrong’s Hot Seven sessions, his absence was clearly felt.

Even though he did not lead any record dates of his own in Chicago, it would be difficult to imagine the Chicago jazz scene of the 1925-28 period without Ory. As a member of Louis Armstrong’s Hot Five during 1925-27, his rhythmic style and gruff sound served as a perfect contrast to Armstrong. On such pieces as “Gut Bucket Blues,” “Come Back Sweet Papa,” “Jazz Lips,” a remake of “Ory’s Creole Trombone,” and his own “Savoy Blues,” Ory provided a perfect backdrop for Armstrong’s flights. He also had the chance to make the recording debut of his most famous original “Muskrat Ramble” on February 26, 1926. To show his importance in these recordings, when the trombonist was on tour with King Oliver and missed being part of Armstrong’s Hot Seven sessions, his absence was clearly felt.

The association with Armstrong was almost entirely in the recording studios. For his regular job, Ory was part of King Oliver’s popular group and a strong part of such recordings as “Too Bad,” “Snag It,” “Jackass Blues,” “Sugar Foot Stomp.” Jelly Roll Morton was also fond of Ory’s playing and he utilized him on some of his most important recordings including “Black Bottom Stomp,” “The Chant,” “Sidewalk Blues,” and “Doctor Jazz.” In addition, Ory recorded with Luis Russell’s Hot Six, Lil Armstrong, Irene Scruggs, Ma Rainey, Butterbeans and Susie, Tiny Parham, and the Chicago Footwarmers. Some of his most fun performances are the four songs apiece he cut with the New Orleans Bootblacks and the New Orleans Wanderers in 1926, which were essentially Armstrong’s Hot Five but with George Mitchell on cornet and Joe Clark added on alto. The ensemble-oriented music (which included such titles as “Gatemouth,” “Too Tight,” and “Papa Dip”) feature Ory playing alongside Johnny Dodds and the results are consistently exciting.

Pause

But then it stopped for a time. After King Oliver headed to New York, Ory worked nightly with Dave Peyton, Clarence Black, and, in 1929, with Boyd Atkins’ Chicago Vagabonds. Rather than follow the trend and move to New York, Ory decided to return to Los Angeles. He would have a low profile for the next dozen years. He worked with local bands before dropping out of music altogether in 1933, getting a day job and for a time helping his brother run a chicken farm. With the rise of the swing era and big bands, the jazz world seemed to have passed him by.

Revival

In 1942 with the rise of interest in New Orleans jazz, Kid Ory returned to music. He worked with clarinetist Barney Bigard’s group and led his own quartet in Los Angeles, sometimes doubling on bass. A surviving radio broadcast from 1943 finds him playing with Bunk Johnson. It is the first documentation of Ory’s playing since 1928 and shows that the 57-year old trombonist had not lost a thing.

Orson Welles, a fan of jazz, hired Kid Ory in 1944 to provide some New Orleans jazz for his weekly radio show, playing one song per program. The feature (which had Ory leading a septet that included Mutt Carey, clarinetist Jimmie Noone and drummer Zutty Singleton) became so popular that it launched his comeback, giving his career a momentum that did not stop until his retirement. The Crescent label was founded specifically by Nesuhi Ertegun (who later on was a force for the Atlantic label along with his brother Ahmet) to record Ory. Ory’s group with Omer Simeon, Darnell Howard, Barney Bigard, or Joe Darensbourg on clarinet in place of the recently deceased Noone, began to become quite popular, particularly in California. While Carey’s playing was more primitive than it had been in the 1920s, the band had an attractive sound and swung hard.

Sidemen

Kid Ory appeared in the Louis Armstrong film New Orleans in 1946 and cut a session as a sideman with Armstrong that included the original version of “Do You Know What It Means To Miss New Orleans.” Ory’s own group evolved through the years. Trumpeter Andrew Blakeney succeeded Carey in 1947 and gave the band a solid lead with Joe Darensbourg sounding fine on clarinet. The powerful trumpeter Teddy Buckner took over in 1949 and adapted his style to the Ory approach. By 1953, Ory and Buckner were joined by clarinetist Bob McCracken and the great stride pianist Don Ewell, making their first recordings for the Good Time Jazz label.

However my favorite of all of Ory’s groups (which were called Kid Ory’s Creole Jazz Band) was his 1954-56 unit with trumpeter Alvin Alcorn, Ewell, and either George Probert or Phil Gomez on clarinet. Alcorn’s mellow tone, the way that he gradually built up ensembles, and the exciting note that he invariably hit leading into the final chorus worked perfectly with Ory and resulted in many exciting performances. Their Good Time recordings are some of the most stirring New Orleans jazz of the 1950s.

With trumpeter Marty Marsala and clarinetist Darnell Howard, the Ory band continued working steadily in 1957. Teddy Buckner returned for a period the following year and then in 1959, Henry “Red” Allen surprised many by joining Ory’s band along with clarinetist McCracken. Allen, who was a more modern player than Ory, thought of him as an important elder and was honored to be in his band, touring Europe. In 1961, with Andrew Blakeney back in the trumpet spot, Ory made his final recordings. 74 at the time, he had not lost enthusiasm or skill in his playing, but he felt that it was time to slow down.

Retirement

While Kid Ory broke up his band at the end of 1961 and considered himself retired, he still played now and then. In 1964 he appeared on a Walt Disney television special, performing on the riverboat Mark Twain with Louis Armstrong and Johnny St. Cyr (from the Hot Five) and sounding fine. He moved to Diamondhead, Hawaii, in 1966. In 1971, Ory returned to New Orleans for the final time, playing in a parade at the Jazz and Heritage Festival. Part of his set that week in a group with trumpeter Thomas Jefferson, clarinetist Raymond Burke, and Don Ewell was issued years later by the Upbeat label, his only recording after 1961.

While Kid Ory broke up his band at the end of 1961 and considered himself retired, he still played now and then. In 1964 he appeared on a Walt Disney television special, performing on the riverboat Mark Twain with Louis Armstrong and Johnny St. Cyr (from the Hot Five) and sounding fine. He moved to Diamondhead, Hawaii, in 1966. In 1971, Ory returned to New Orleans for the final time, playing in a parade at the Jazz and Heritage Festival. Part of his set that week in a group with trumpeter Thomas Jefferson, clarinetist Raymond Burke, and Don Ewell was issued years later by the Upbeat label, his only recording after 1961.

Kid Ory passed away from pneumonia on Jan. 23, 1973 in Honolulu at the age of 86, a New Orleans jazzman to the end.

Read our review of the definitive Kid Ory early years biography: Creole Trombone

Hear a selection of 155 Kid Ory recordings at Jazz-On-Line.

Since 1975 Scott Yanow has been a regular reviewer of albums in many jazz styles. He has written for many jazz and arts magazines, including JazzTimes, Jazziz, Down Beat, Cadence, CODA, and the Los Angeles Jazz Scene, and was the jazz editor for Record Review. He has written an in-depth biography on Dizzy Gillespie for AllMusic.com. He has authored 11 books on jazz, over 900 liner notes for CDs and over 20,000 reviews of jazz recordings.

Yanow was a contributor to and co-editor of the third edition of the All Music Guide to Jazz. He continues to write for Downbeat, Jazziz, the Los Angeles Jazz Scene, the Jazz Rag, the New York City Jazz Record and other publications.