In the realm of studying ragtime history, importance is often given to the banjo, and rightfully so. Some of the best sources of authentic ragtime recordings are of banjo with piano accompaniment. At the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries, banjoists were highly praised musicians, and those such as Vess Ossman and Ruby Brooks were considered among the best. While many people came to know the banjoists, many also got to know the pianists that traveled with them. The accompanists were very important to each banjoist, as they provided the foundation for all banjoist’s rhythm and skill. Many of these accompanists faded away with time, but a few had the rare chance to be recorded, thus we can hear them today. Despite each recording lab having its own group of pianists, banjoists often brought in their favorites, and one was regarded higher than the rest, Jacob, or “Jackie” Silberberg.

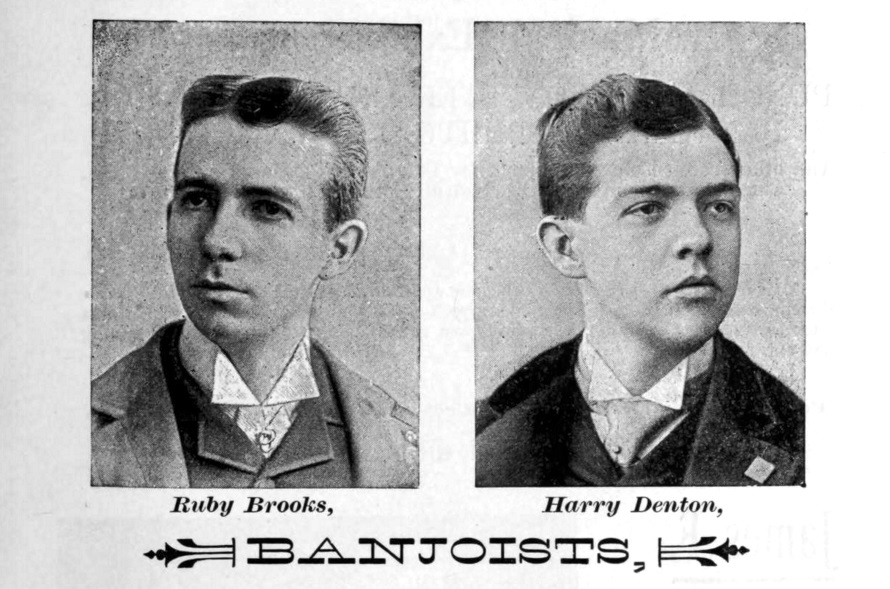

Phipps Musical and Lyceum Bureau – List of Attractions, 1892.

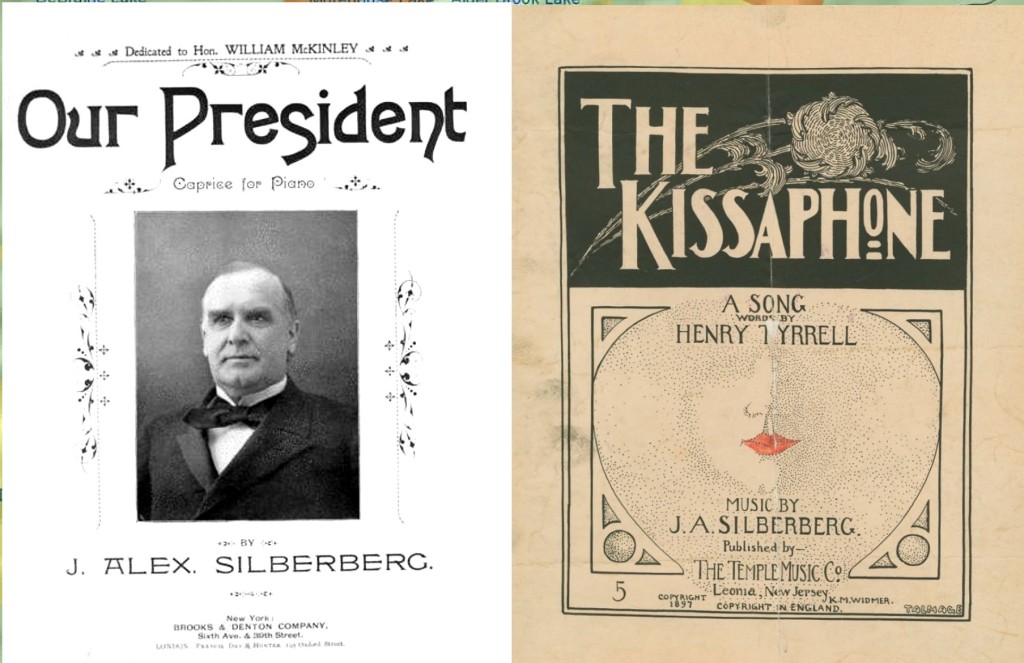

Silberberg is still a very mysterious character, who is unusually difficult to track. He, like many working musicians, kept a low profile, and kept to their work. Finding any information on him is difficult for this reason. According to public records, he was born in 1864, and his father Alexander was also a musician, originally coming from Prussia (now Poland). Jacob was the oldest of six children, and like many Jewish immigrants, they lived on the Lower East Side. And also like many children of musicians, Jacob was already working by age 15. By 1884, he was working with the up-and-coming banjo extraordinaire Ruby Brooks. By the late 1880s and early ’90s, Ruby Brooks and Harry Denton were almost always seen with Silberberg. Their act was plastered all over various newspapers and programs. One paper in 1893 stated:

Brooks and Denton, with J. Alex. Silberberg, pianist, are celebrated throughout the civilized world, having played before all the crowned heads of Europe and their claim to be America’s representative banjoists has been well sustained by their excellent performances.

Countless papers highlighted the popularity of their act, and just like Ossman, they toured all over. Brooks didn’t get involved in recording until the late 1890s, so it is uncertain if Silberberg followed Brooks into the recording labs.

For decades, it has been an essential question to recording and ragtime historians who Vess Ossman had accompanying him on his many recordings. There is no single answer to this question, but a rather obvious observation within the Victor ledgers can bring our attention to Silberberg. On May 16th, 1901, Ossman made a few recordings that have since become famous to ragtime historians. On that Thursday, Ossman recorded such titles as “Rusty Rags,” “Mosquitoes Parade,” “My Blushing Rosie,” etc.

It was a prolific day for Vess, but that was also the day that Silberberg made two piano solos (it is also noteworthy that the day before, Silas Leachman made some of his most famous recordings). Unfortunately, no copies of these two solos have yet been found. They show up in the Victor ledgers as specific numbers, so the possibility that they may exist somewhere is very possible. Aside from the trivial piano solos, the recordings Ossman made on this day can give us a very good understanding of why banjoists liked Silberberg so much. One thing to note on these recordings is that Silberberg kept the exact same tempo throughout the play time. In an era with limited run time, this is notable, as few studio accompanists were able to achieve this.

However, it’s important to note that Silberberg wasn’t on all of Ossman’s Victor recordings. For example, his previous session for them, on January 21st, 1901, is a distinctly different accompanist. Ossman for years had preferred Frank P. Banta as his accompanist. From the early 1890s, Banta toured with Ossman. By the end of the decade, he likely preferred Banta on most of his recordings. It seemed like a special treat when Silberberg could make records with Ossman or Brooks.

A great way to compare the distinctive styles of these accompanists is by listening to a few of Ossman’s January 21st, 1901 Victors and then to his May 16th Victors. The differences are remarkable. From listening to them, we can be sure that Banta was on the January session, and Silberberg the May session. Silberberg had likely not been as familiar with recording as Banta, and when comparing these sessions, one can note how much more aggressive the attack on the piano is on the January session than the May session. Banta, though known for his dexterity, was heavy handed as a pianist, as was essential for making recordings.

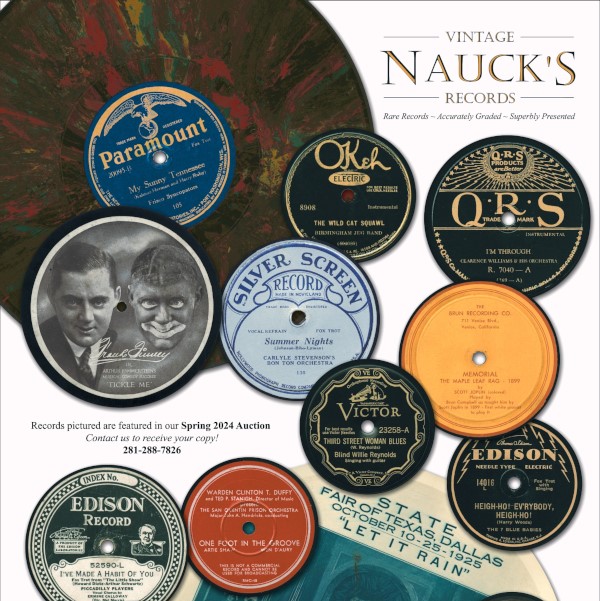

Another batch of records to take a second listen to are the Ruby Brooks records. Brooks didn’t make very many records, but they are prized to collectors today. Brooks was completely self-taught, distinguishing him from all the other famous banjoists of the time. Brooks made a batch of Edison records between 1898 and 1903, 3 Zon-O-Phones, and in 1901 a few Climax/Columbia discs. It is more likely that Banta accompanied Brooks on his Edison cylinders, as it would have been easier to use the lab pianist, who also happened to be a pianist that Brooks knew relatively well. Edison’s management generally didn’t welcome accompanists brought in by the artists, as they ran a tight operation and liked to have things set up a specific way for each session.

Perhaps the most unusual records that Brooks made in his time recording were the Climaxes. These were recorded extremely well for the period, but in a more unexpected aspect, the accompaniment. It seemed that Brooks did more than one session for Climax, as some of the records have distinctly different pianists, much like the Ossman Victors. One session likely has Fred Hylands, and the other Silberberg (based on the Ossman Victors). The accompaniment is significantly busier on one session, and it’s likely that’s Hylands. The reason for this unusual balancing issue is likely what I mentioned above about Silberberg. He wasn’t as familiar with recording as someone like Hylands or Banta. It would have been safer for the engineers to place more emphasis on Silberberg if his playing wasn’t as loud as the regular accompanists. This is only a theory of course, but it could explain the stark contrast between piano volume compared to regular Climax records, as it really is quite shocking.

Of course, the preference for pianists accompanying banjoists diminished after Banta’s death in 1903, and even more so after the death of Brooks in 1906. But the tradition remained, as pianists like Banta’s son (Frank Edgar) and Felix Arndt were known as accompanists for Fred Van Eps in the 1910s.

As for Silberberg, he lived the typical life of a working musician, working any gigs he could get, and also working in theater orchestras. He never married, and often lived in boardinghouses. Even after the death of Banta and Brooks, Silberberg remained a well-respected pianist in the music world, as in 1903, a large fundraising event was held in his honor. The specifics of why exactly were not stated in any sources. Silberberg was in poor health for years, and he died suddenly at the very end of 1912. His quick demise was duly noted in several publications. One obituary stated thus:

Mr. Silberberg had suffered for years from an affection of the eyes, and the most eminent specialists pronounced his case hopeless, but even under this terrible handicap he maintained his sunny disposition and continued his work of composition up to the day of his sudden death.

Even if he is still relatively unknown today, we can still hear his once-famous accompanists behind Ossman and Ruby Brooks. Hopefully someday his two piano solos will be discovered.