Set forth below is the thirty-fifth “Texas Shout” column. The concluding installment of a two-part essay, it first appeared in the December 1992 issue of The West Coast Rag, now The Syncopated Times. Read the first part HERE. The following note was added when this column was reprinted in April 1999.

Set forth below is the thirty-fifth “Texas Shout” column. The concluding installment of a two-part essay, it first appeared in the December 1992 issue of The West Coast Rag, now The Syncopated Times. Read the first part HERE. The following note was added when this column was reprinted in April 1999.

Because the text has not been updated, I should mention that I retired from reviewing records at the end of 1997, thereby closing down my “This Month’s Records” column. Moreover, seeing no point in reprinting detailed comments on recordings issued in 1992, I have tacitly eliminated seven paragraphs that reviewed the two Uptown Lowdown Jazz Band recordings mentioned in the latter portion of the article. Because this deletion gives me a little extra space, I have added a note at the end of the essay explaining why the thirty-sixth “Texas Shout” will not be reprinted.

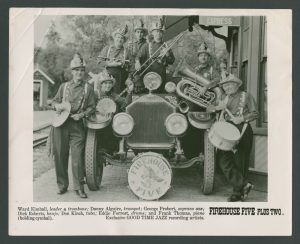

I was introduced to Dixieland jazz via the West Coast revival style, first through the Firehouse Five Plus Two and then Turk Murphy and Lu Watters. Turk is, as many of you know, my all-time favorite musician. Although I have come to enjoy all seven styles of Dixieland, plus certain closely-related music, I still feel a special response to a Yerba Buena-ish combo in full cry or to a rusty-gate Murphy-ish trombone solo.

Even so, from time to time in this column, I’ve done a little scolding of certain elements of the Dixieland community that has probably fallen most heavily on West Coast revivalists. I’ve done so because there is a pernicious type of archivalist mentality afoot among Dixielanders that, without meaning to do so, actively works to stop the music dead in its tracks and turn it into a museum piece – and this attitude is more apparent among West Coast revival musicians and their fans than in other styles.

I know whereof I speak. Coming to the music through Turk, as I did, I couldn’t help but admire his dedication to digging out underplayed gems and presenting them with obvious respect for their sources.

I strove to follow what I interpreted as Turk’s lead. In chording numbers for my Red Lion Jazz Band, I always tried to get the original sheet music, faithfully setting down each passing chord exactly as it was in the piano score. I always tried to check out the “original” recording, to see if it contained special strains or features that I needed to include to “legitimize” the Red Lions’ presentation.

However, two things happened that helped me put such research and effort into a different perspective. One was my increasing involvement in reviewing all kinds of Dixieland records and the other was recurrent conflicts among (1) the sheet music scores, (2) the vintage recording(s), and, sometimes, (3) my own musical instincts.

As I did more record reviewing, a broad range of review copies began arriving at my door, some of which were in styles of Dixieland that I hadn’t initially preferred or to which I’d paid little attention. Wanting to be as fair and objective as possible in assessing each one, even if it was a recording that I might not have purchased for myself, I tried to review the record from the point of view of the artist – to determine what his objectives were, how well he’d achieved them and, along the way, whether I thought the objectives were worthy ones.

I found myself discovering new elements of the music, ones that were not emphasized as much in West Coast revival Dixieland, but ones which were enjoyable and valid on their own terms. I came to recognize that the common elements among all styles of Dixieland (in addition to the basic musical vocabulary) are heat and swing, and that a lack of these two elements cannot be compensated for via obscure repertoire, ingenious arrangements or anything else.

As dozens of albums flowed in each year, I also came to put a premium on creativity within the idiom. I received lots of competent, swinging, enjoyable discs by bands that were happy to walk the middle of the road, to play the standard tunes typically utilized within their particular branches of Dixieland, and to play them the customary way. I could, and still do, give these recordings a recommendation that tells the reader they’re worth their cost (the equivalent of a “three stars out of five,” or an average, rating in my “This Month’s Records” column for WCR). However, when you’ve heard as many records as I have, and if you believe (as I do) that Dixieland is an art form and not just background music for good times, you are going to save your highest ratings for musicians and bands having something original to say.

One of the conflicts referred to above occurred whenever I noticed that the original sheet music might have a passage that would be very interesting when rendered by a solo piano (song sheets are typically scored for voice and solo piano), but would be awkward for a full band to handle smoothly. Sometimes, while working over the tune at the keyboard, my hands and mind would want to skip past a passing chord in the music to get a stronger feeling of forward momentum. Should I follow my instincts and chart the swinging chord pattern, or should I force the Red Lions to fight their way through the “right” one?

Other conflicts occurred between the sheet music and the recordings with respect to melody line or chords. Which was “right”?

Moreover, as my LP collection expanded, I realized that there were several vintage recordings of certain tunes, each of which could be considered an “original” recording. Which of those was “right”? Bix’s 78 of “Rhythm King” opens with a horns-only introduction, while the Coon-Sanders Nighthawks begin with a scored Charleston-like stoptime figure. Why was Bix’s version always turning out to be the one everybody played?

Contemplating these questions, I decided to resolve such conflicts by making the choice that I thought would lead to the greatest amount of heat and swing in the Red Lions’ performance of the tune. As I became more and more convinced that this was the correct way to go, I began to re-examine some of the premises I’d been following, and had been discussing with other West Coast revival disciples. I decided that too many of us were misreading the scriptures as laid down by Watters and Murphy.

Because the Yerba Buenans were reacting against the prevalence of Chicago style jazz in 1940, its devotees have sometimes read the movement as one in which anything that smacks too much of Chicago is to be avoided at all costs. They won’t perform tunes that the Chicagoans typically play, no matter how good those selections are. They’ll avoid any musical devices normally employed by Chicagoans, even if those devices help get the tune to heat up and swing harder.

Because the Yerba Buenans sought out underplayed tunes, its disciples have sometimes read the movement as demanding that obscure tunes be played – the more obscure the better, regardless of the quality of the tune as a vehicle for swinging jazz. You can, they say, make up for a diminution of swing and heat by playing numbers most people haven’t heard before, and the more unknown a title is, the less swing and heat you need to generate to justify playing it.

(Personally, I think that any musician who tells you that a tune like, say, “Royal Garden Blues” is “exhausted” is copping out. He’s in effect admitting that he has so little imagination and creativity that he needs the help of a tune you don’t know in order to show you something you haven’t heard before.)

Because the Yerba Buenans were record collectors, its disciples have sometimes read the movement as one that insists upon replicating licks from old records as a way of playing the number “correctly.” This reading has been carried to an extreme by bands that today will deliver, virtually note for note, exact renditions of performances by Lu Watters’ Yerba Buena Jazz Band and Turk Murphy’s San Francisco Jazz Band, even though those records were recorded in perfectly acceptable fidelity and are readily available at festival counters and well-stocked record stores. Moreover, fans of these clone bands apparently can’t get enough of hearing these same renditions played over and over.

After a quarter-century of reviewing hundreds of records, I have little patience with musicians who deliberately avoid creativity and try to justify such action by citing what some jazzman in the past has done. All of the vintage jazzmen revered by today’s copyists were themselves originals. I defy you to find a Lu Watters record that sounds anything like any previous waxing of the same tune. Furthermore, Watters and Murphy made no attempt to avoid worthwhile tunes, whatever their source.

In short, the original West Coast revivalists were exceptionally creative people. Imitating their work may be well-intentioned, but it is not really going to keep vitality in the style. To pay tribute to Watters and Murphy in the proper way, a musician should get under the skin of their style, get below the mere notes played on the records and understand the approach so well that he plays it as naturally as breathing. Then he should do what the Yerba Buenans did – play West Coast revival, but with his own distinctive stamp.

I have preached this sermon before in this column. However, it is an important one to hear, I think, if you want the style to live, to grow beyond regurgitation of past triumphs.

I was inspired to go through this diatribe once again by the arrival at my home of review copies of two albums by a band that plays West Coast revival the right way, Seattle’s Uptown Lowdown Jazz Band. One is a 57-minute tape, recorded live on a cruise, entitled “Cruisin’ Avalon” and the other is a 68-minute studio session entitled “Business In F“.

Today’s column really ends here but I’d like to add one footnote before we leave the ULJB. Its devotees have dubbed the band’s sound “Seattle Style”, which probably serves it well as a marketing gimmick. However, don’t be seduced into thinking that Uptown plays a new “style” of Dixieland jazz.

Actually, Dixielanders use the word “style” in two senses. In the smaller sense, each player and band has its own way of playing Dixieland, its own “style” if you will. However, in the larger sense, there are, so far, only seven basic Dixieland styles: white New Orleans, downtown New Orleans, uptown New Orleans, hot dance, Chicago, West Coast revival and British trad. Everyone I’ve heard either fits into one of these categories or operates around the common borderlines between them.

To illustrate: Cornetists Bobby Hackett and Wild Bill Davison did not sound anything like each other. Each had his own instantly recognizable tone – Hackett’s clear and warm, Davison’s tart and saucy. Each had his own “style” of phrasing as well.

However, each was basically a Chicago style Dixielander. Both played regularly with Eddie Condon. Even though their sounds were different, you could replace one with the other in a typical Condon unit and none of the other players would have had to make any significant adjustment to accommodate the change. The basic rules and objectives would remain the same.

So, while one could say that Hackett and Davison each had his own “style,” each operated squarely within Chicago style. So it is with Uptown Lowdown’s “Seattle Style”, which is squarely within West Coast revival.

✦ ✦ ✦ ✦ ✦

In an effort to assist readers who wanted to understand the Dixieland and ragtime scenes in more depth, the thirty-sixth “Texas Shout,” published in the February 1993 issue, dealt with then-current periodicals devoted primarily to these musics. I mentioned the ones I favored, described their coverage, and listed their addresses and subscription prices.

I am eliminating that essay from this current series of reprints because the changes since 1993 with respect to this type of periodical have been quite dramatic, thereby reducing the article to a purely historical snapshot. For example, at this writing, I receive only two of the six Dixieland periodicals covered.

Jazz Journal International became prohibitively expensive to import from England. Storyville is no longer published. Jersey Jazz, like much of the Dixieland scene, started to de-emphasize Dixieland in favor of swing and progressive, jazz styles in which I have much less interest. The Second Line stopped appearing regularly, becoming a once-in-a-while compendium, too much of which consisted of reprinted articles by Floyd Levin that I had previously seen in other periodicals.

The changes referred to above in the Dixieland periodical scene occurred for two reasons. First, the continuing steep, steady diminution of the audience for Dixieland causes increasing difficulty in justifying the work required to produce a quality periodical aimed at its audience. Second, most periodicals in this field are basically labors of love created by one person, sometimes with a few helpers, and are likely to fold or sharply change direction if that person, for whatever reason, leaves the helm.

As I write, the two largest-circulation independent U.S. periodicals dealing with older-style jazz are The American Rag (now The Syncopated Times) and The Mississippi Rag (9448 Lyndale Ave. So. #120, Bloomington, MN 55420, phone 612-885-9918). Although they have many of the same ads and listings for upcoming events, they have very little overlap in textual coverage. I recommend both.

The full run of “Texas Shout” has been collected into a lavishly illustrated trade paperback entitled Texas Shout: How Dixieland Jazz Works. This book is available @ $20.00 plus $2.95 shipping from Tex Wyndham, On request, Tex will autograph the book and add a personalized note (be sure to tell him to whom the note should be addressed).

Tex Wyndham’s 3 CD Guide to Dixieland with music and commentary is available for $20 plus $2.95 shipping. The separate CD, A History of Ragtime: Tex Wyndham Live At Santa Rosa, is available for $13.00 plus $2.00 shipping. On request, Tex will autograph the inner sleeve and add a personalized note (be sure to tell him to whom the note should be addressed).

Send payment to Tex Wyndham, P.O. Box 831, Mendenhall, PA 19357, Phone (610) 388-6330.

Note: All links, pictures, videos or graphics accompanying the Shouts were added at the discretion of the Syncopated Times editorial staff. They did not accompany the original columns and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of Tex Wyndham.

From roughly 1970-2010, Tex Wyndham was: (1) one of the best-known revivalist Dixieland jazz musicians in the US, as cornetist, pianist and bandleader, (2) one of the best-known ragtime pianists in the US, and (3) one of the most respected critics in the US of Dixieland jazz, ragtime, and related music. He is the only person about whom all three of those statements can be made.