Set forth below is the sixty-sixth “Texas Shout” column. The concluding installment of a two-part essay (part 1), it first appeared in the October 1995 issue of The American Rag and deals with a then-pending proposal to have the Federal government fund a national park for jazz. The text has not been updated, but I will mention that the Armstrong postage stamp discussed therein was issued.

Set forth below is the sixty-sixth “Texas Shout” column. The concluding installment of a two-part essay (part 1), it first appeared in the October 1995 issue of The American Rag and deals with a then-pending proposal to have the Federal government fund a national park for jazz. The text has not been updated, but I will mention that the Armstrong postage stamp discussed therein was issued.

Additional supplemental data appears following the reprinted material below that was added to a previous reprint in November 2003. To set the context, the first installment described a phone call in which a friend of mine implied that, because I did not support the national park proposal, I was not “for” jazz.

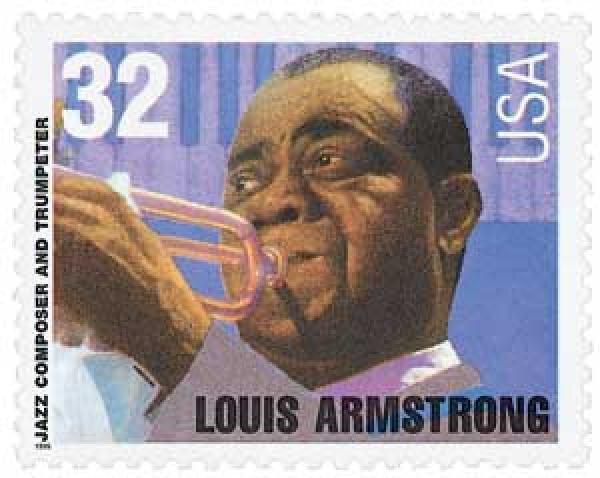

Let me begin by saying that if – and this is a big if – the government is going to fund the arts, then Dixieland should get its fair share thereof, which it doesn’t do now. Similarly, if – another big if – the government is going to pay someone to sit around and tinker from time to time with postage stamp designs, then Louis Armstrong is long overdue to be honored thereon.

(As an aside, this is a perfect example of the Federal government’s unerring instinct for grasping the wrong end of the stick. A respectable case can be made that Satchmo is the most important and influential musician ever born in this country, yet at this writing his image has never graced a U.S. postage stamp – although this disgraceful situation may have been rectified by the time this column appears. By contrast, the question of which pose of Elvis Presley (!!!) should appear on a stamp was deemed of sufficient importance that the postal service conducted a national referendum on its two choices – and then, if memory serves, printed both versions anyway.)

(As an aside, this is a perfect example of the Federal government’s unerring instinct for grasping the wrong end of the stick. A respectable case can be made that Satchmo is the most important and influential musician ever born in this country, yet at this writing his image has never graced a U.S. postage stamp – although this disgraceful situation may have been rectified by the time this column appears. By contrast, the question of which pose of Elvis Presley (!!!) should appear on a stamp was deemed of sufficient importance that the postal service conducted a national referendum on its two choices – and then, if memory serves, printed both versions anyway.)

However, my deeply held view is that the government should do the absolute minimum required to govern and, in all other respects, leave us alone to get on with our lives. I think that using tax dollars to support the arts is not required for the task of government. In particular, I am opposed to using tax dollars to fund the arts, including funding Dixieland jazz and ragtime.

Let’s put aside the fact that our Federal government currently runs a substantial deficit and needs to find ways to cut spending. Let’s also overlook recent well-publicized fiascoes in which Federal funds were used to subsidize activities so far removed from a rational definition of “art” that, except for being propped up by the government, they would have disappeared instantly into the oblivion they deserve.

Even if we had intelligent government officials (an oxymoron?) running the show, I wouldn’t go for it. I think that, if an art form can’t make it in the commercial marketplace, then it should be maintained on a hobby basis (as Dixieland and ragtime have pretty much been for decades now).

Further, if there aren’t enough hobbyists interested in it to keep it alive, then it might as well fade from the scene. Why should our tax dollars be spent to preserve something for which no one cares much?

An aspect of the problem that is rarely discussed revolves around the situation that, in a free economy, virtually any element of popular culture, once it has had its day, can be viewed as “art,” a part of our heritage that needs to be saved for posterity. These include matchbox covers, advertising materials, automobile hood ornaments, doll houses and their furniture, soft drink bottles, kitchen reamers (to crush juice from fruit), teddy bears, railroad cars and engines, comic books, mustache cups, on through an endless list of everything you could name, even entire buildings (we already pay for maintaining those now as, I believe, National Historic Sites).

You and I might think that Dixieland jazz, one of America’s earliest native-born art forms, obviously ought to rank higher on the scale than many of these other items. However, I’ll bet someone who has spent his life collecting old model trains wouldn’t agree. I’m sure he’s just as opposed to having his tax money spent on Dixieland jazz as I am to having mine spent on model trains.

Yet there isn’t enough money to preserve everything that could legitimately claim to be art. I wouldn’t be presumptuous enough to say that my special interest outweighs someone else’s. Government officials, of course, love to make such sweeping decisions, but who trusts them anymore to come close to getting things right?

Thus, I think it best to let each “art” community take care of its own to the extent that it wants to do so. If it doesn’t want to do so, then it shouldn’t try to extract money from folks who don’t care about it.

Let’s say, though, that government is going to fund the arts. Does that mean that a national park for jazz is our most pressing need in this respect? Not in this household.

As most of you know, Nancy and I are deeply committed movie buffs. We particularly enjoy silent movies.

Most silent movies were filmed and printed before safety stock was invented. They were produced on nitrate-based film, a highly inflammable substance that, if not maintained at exactly the proper temperature and humidity, will deteriorate into dust. Even under ideal conditions, nitrate film does not have an unlimited shelf life.

I can’t pinpoint the source, but I recall reading that, partly as a result of fires and inappropriate storage, over 90% of all the silent films ever made no longer exist. Of the remainder, there are quite a few in the vaults of film archives around the country that, for lack of funding, aren’t being preserved on safety stock and are slowly but surely wasting away.

We are not talking here about a side issue like a national park for silent movies. In this case, the art form itself has substantially disappeared from the face of the earth. Unless funds are found, and soon, to do the job of conversion, some of the small portion of it still around is going to suffer the same fate.

Thus, much as I love Dixieland, if I were going to advocate spending money on arts in which I am personally interested, I would much rather see the funds go toward the immediate and pressing need to preserve what silent movies remain to us. As a fan of fantasy and horror literature (we’ve been to the World Fantasy Convention ten times), much of which was originally published decades ago in pulp magazines printed on the cheapest possible paper, I feel much the same way about trying to save pulps that would otherwise crumble to pieces.

Let’s assume that we’re past that point, though, and have decided that we will use government funds to support Dixieland jazz in some way. Is the establishment of a national park our first choice? Which others were considered?

Nancy and I have had a little experience with such monuments. I’ll preface the tales by conceding that this is anecdotal and may not represent the generality. Also, I don’t know how much, if any, public money was involved in these instances.

On our first trip to New Orleans, we discovered that we were in the midst of the French Quarter festival, a delightful affair in which excellent Dixieland bands were playing all day for the public’s free enjoyment at stages set up along French Quarter streets. One would think that, at such a time, interest in Dixieland jazz among the general public would be heightened.

It was a pleasant spring afternoon, a good day for a walk. So, after enjoying some jazz, we decided to try to locate the New Orleans Jazz Museum, containing rare and valuable memorabilia associated with some of our favorite musicians. It turned out to be in a building not far from the musical action.

We were fascinated by the instruments, sheet music and other items displayed from the early days of New Orleans jazz. We had plenty of time to examine them, because while we were there, no more than three other people were looking at the exhibits.

After we left the museum, we took another short walk to a park containing a large impressive statue of Louis Armstrong. It was quite a lovely setting; we lingered a while and even took our picture with Pops. During the entire time we were at the spot, there wasn’t another human being anywhere in sight.

Perhaps we were there on an off day, but I doubt it. Any at rate, whatever those two projects cost, it didn’t seem to us as though the public was extracting much value therefrom.

We’ve had essentially the same experience when we visited other establishments commemorating important Dixieland figures. For example, we were the only ones in attendance the time we stopped at W.C. Handy’s birthplace and museum in Florence, Alabama.

Would a jazz national park suffer the same fate? Would the funds to be earmarked for Dixieland be better used to, say, preserve sheet music cover art? To reprint rare jazz tunes in commercial editions so that today’s Dixieland bands can get access to and play them? To fund oral history interviews with important veteran jazzmen/women? To finance a search for the fabled trunk left behind by Scott Joplin that just might contain his lost opera and other unpublished manuscripts? To produce recordings so that the public can more easily appreciate the heritage of Dixieland jazz (to my knowledge, there never has been a U.S.-produced album devoted entirely to The Halfway House Orchestra of New Orleans, one of my all-time favorite bands)? To present Dixieland concerts? To establish courses at which Dixieland history and performance are taught?

Would a jazz national park suffer the same fate? Would the funds to be earmarked for Dixieland be better used to, say, preserve sheet music cover art? To reprint rare jazz tunes in commercial editions so that today’s Dixieland bands can get access to and play them? To fund oral history interviews with important veteran jazzmen/women? To finance a search for the fabled trunk left behind by Scott Joplin that just might contain his lost opera and other unpublished manuscripts? To produce recordings so that the public can more easily appreciate the heritage of Dixieland jazz (to my knowledge, there never has been a U.S.-produced album devoted entirely to The Halfway House Orchestra of New Orleans, one of my all-time favorite bands)? To present Dixieland concerts? To establish courses at which Dixieland history and performance are taught?

As I see it, these questions are not easily answered. I very much doubt that the Federal government is in a better position to weigh alternatives than the jazz community itself.

Thus, I think that the government should stay out of the whole business and let members of the jazz community utilize their private funds as they see fit. The same goes for the model plane community, the cigar band community, and so on down the line.

There you have my view. If you disagree, fine. If you think I’m somewhere to the right of Attila The Hun on this topic, that’s O.K., too. We’ll kick it around over that beer I mentioned.

Tell me, though. After reading my thoughts on this subject, do you really see me as someone who isn’t “for” jazz? Have I actually been kidding myself all these years?

* * * * *

The “national park” for jazz was brought into being, if you can call a moderately sized room in a strip-mall-like building near the intersection of Decatur and N. Peters Streets in New Orleans a “national park”. On the several occasions when my wife Nancy and I have passed by, we have observed that it contains a small stage, an attendant who handles both sales and information regarding the park, and sale racks containing CDs, books and music (virtually all of which are available at nearby stores).

The “park” does sponsor periodic concerts at this site, which are (I think) free to the public, so it is supplying some work for local musicians. However, I can’t help but note that the same purpose could be accomplished more cheaply if the government simply hired the bands to play from time to time at the myriad of public areas around the French Quarter.

The taxpayers would thereby be saved the cost of renting and maintaining the room, paying the attendant, and publishing/mailing the periodic glossy progress-report booklets sent to various individuals. The nearby stores would also be relieved of competition with the Federal government regarding sales of the merchandise.

I do not read the progress reports which, as of this writing, are, for unknown reasons, sent to me regularly. However, Nancy does read them and tells me that there are plans to move from the room to a larger site near the Louis Armstrong statue, a project which might be realized to some degree by the time these words see print. Maybe some good will come of this yet, but I’m not holding my breath.

Also read part 1: Texas Shout #65 Lobbying for Jazz

Want to read ahead? Buy the book!

Want to read ahead? Buy the book!

The full run of “Texas Shout” has been collected into a lavishly illustrated trade paperback entitled Texas Shout: How Dixieland Jazz Works. This book is available @ $20.00 plus $2.95 shipping from Tex Wyndham, On request, Tex will autograph the book and add a personalized note (be sure to tell him to whom the note should be addressed).

Tex Wyndham’s 3 CD Guide to Dixieland with music and commentary is available for $20 plus $2.95 shipping. The separate CD, A History of Ragtime: Tex Wyndham Live At Santa Rosa, is available for $13.00 plus $2.00 shipping. On request, Tex will autograph the inner sleeve and add a personalized note (be sure to tell him to whom the note should be addressed).

Send payment to Tex Wyndham, P.O. Box 831, Mendenhall, PA 19357, Phone (610) 388-6330.

Note: All links, pictures, videos or graphics accompanying the Shouts were added at the discretion of the Syncopated Times editorial staff. They did not accompany the original columns and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of Tex Wyndham.

From roughly 1970-2010, Tex Wyndham was: (1) one of the best-known revivalist Dixieland jazz musicians in the US, as cornetist, pianist and bandleader, (2) one of the best-known ragtime pianists in the US, and (3) one of the most respected critics in the US of Dixieland jazz, ragtime, and related music. He is the only person about whom all three of those statements can be made.