In the music world, it is easy to overrate the popularity of songs and performers. This is not a new concept, and in terms of the history of recorded sound, it is one of the oldest tricks in the book. In the 1890s the recording business was just getting started, so a lot of how the business actually worked was still being sorted out by those who ran the record labs and even by the artists themselves. Since this decade is so early on in recorded sound, fully understanding the relationship between music publishers and recording labs is difficult, but what there is to study on this topic is quite telling, and seemingly modern in many ways. The idea of the manufactured hit is nothing new.

Beginning in the very early 1890s, the few recording stars there were knew it would be advantageous to promote publishers and composers by recording their songs. One of the earliest examples of this goes all the way back to 1889 when Edward Issler recorded Thomas Hindley’s “Patrol Comique.” This piece was composed in 1886 by the English born Hindley who worked occasionally with Issler’s musicians in the 1880s. With this in mind it would s

You've read three articles this month! That makes you one of a rare breed, the true jazz fan!

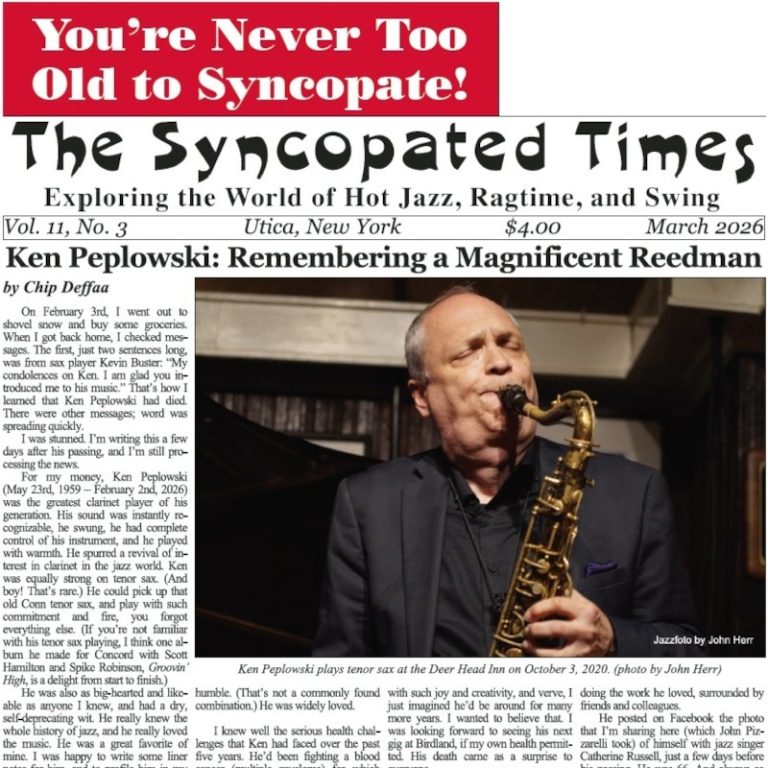

The Syncopated Times is a monthly publication covering traditional jazz, ragtime and swing. We have the best historic content anywhere, and are the only American publication covering artists and bands currently playing Hot Jazz, Vintage Swing, or Ragtime. Our writers are legends themselves, paid to bring you the best coverage possible. Advertising will never be enough to keep these stories coming, we need your SUBSCRIPTION. Get unlimited access for $30 a year or $50 for two.

Not ready to pay for jazz yet? Register a Free Account for two weeks of unlimited access without nags or pop ups.

Already Registered? Log In

If you shouldn't be seeing this because you already logged in try refreshing the page.