This month’s article in this column will step away from the usual type of research done here; this month we will explore a bit of etymology. To begin—in 1904 recording lab bandleader Fred W. Hager wrote a two step entitled “Handsome Harry.” It was a very catchy and infectious piece that was arranged and published by his long time partner Justin Ringleben.

Looking over the sheet itself, one wouldn’t think much of it, as there doesn’t happen to be anything particularly outstanding about the piece, with a simple pattering melody and generic chord progressions. Naturally, the piece was recorded many times not long after its publication, and was quite popular among New York and later London bands and orchestras. But why write an article on this piece alone? The curiosity lies in the context.

In the latter 19th century, many new slang terms and common colloquialisms arose, a lot of them were lost to time, but some are still in use today. One of these more curious terms is Handsome Harry. The author went on a blind search for this term on a quick whim and was entirely shocked by the amount of information to be read. When you look up this term in period and urban dictionaries, the immediate definition can come as a

You've read three articles this month! That makes you one of a rare breed, the true jazz fan!

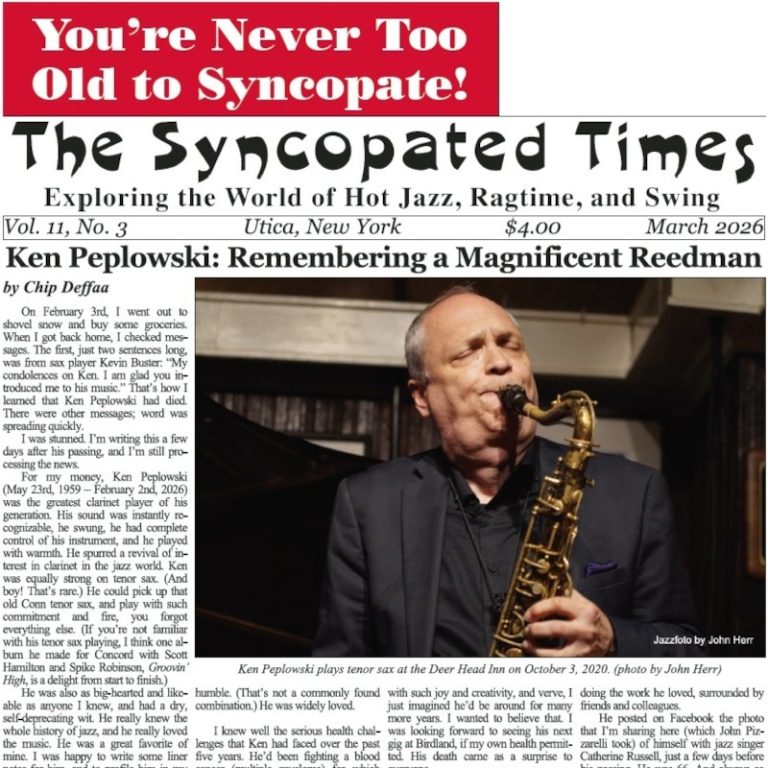

The Syncopated Times is a monthly publication covering traditional jazz, ragtime and swing. We have the best historic content anywhere, and are the only American publication covering artists and bands currently playing Hot Jazz, Vintage Swing, or Ragtime. Our writers are legends themselves, paid to bring you the best coverage possible. Advertising will never be enough to keep these stories coming, we need your SUBSCRIPTION. Get unlimited access for $30 a year or $50 for two.

Not ready to pay for jazz yet? Register a Free Account for two weeks of unlimited access without nags or pop ups.

Already Registered? Log In

If you shouldn't be seeing this because you already logged in try refreshing the page.